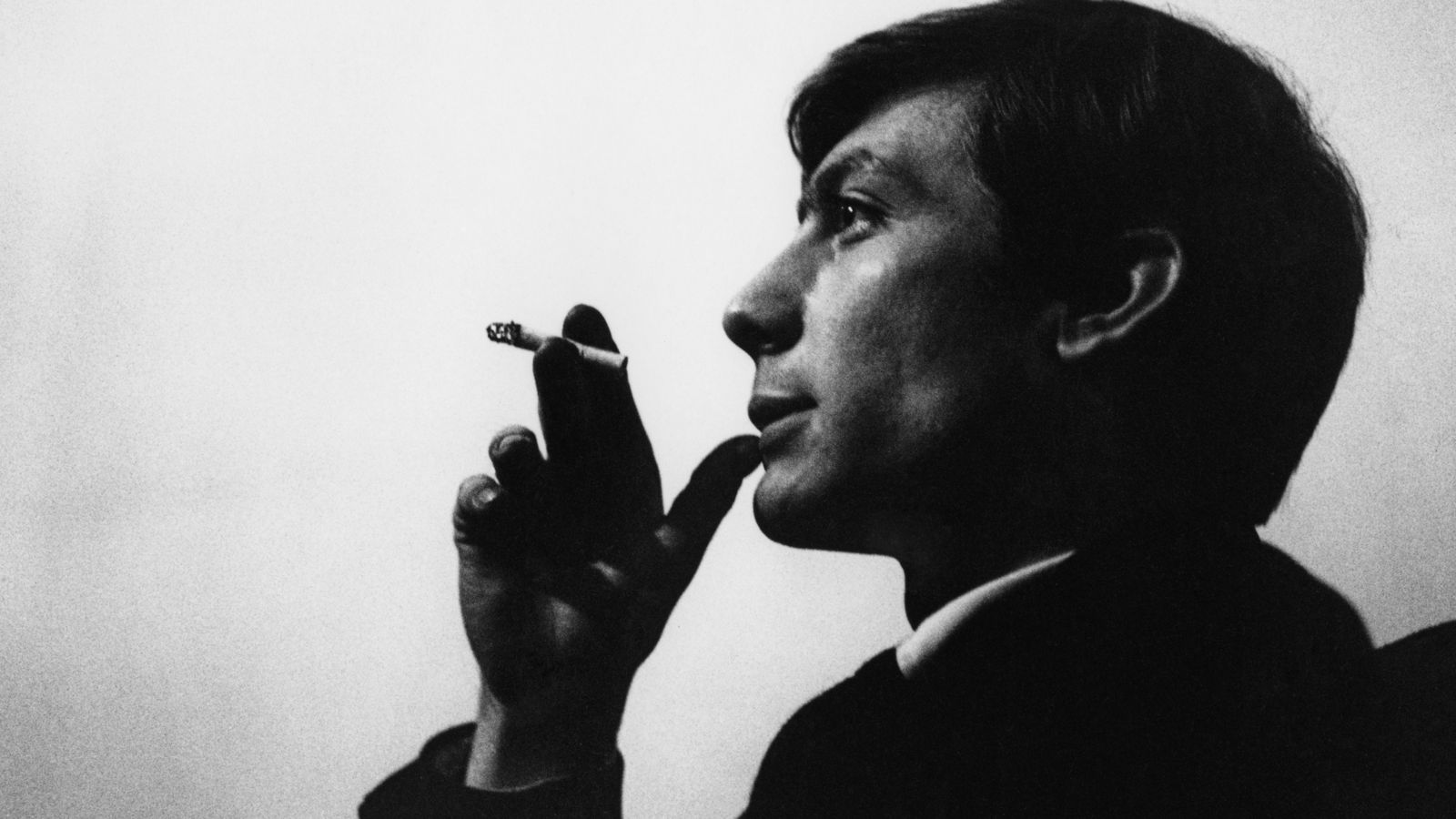

(Jeremy Fletcher/Redferns/Getty Images)

(Jeremy Fletcher/Redferns/Getty Images)

Charlie Is My Darling

F***.

He was, by a preponderance of accounts, the nicest man in rock and roll, the most impeccably dressed, self-effacing to a fault, the center of gravity of the most important rock and roll band that ever was, and therefore the center of gravity of everything, a master of pockets and of swing, uninterested in the trappings of rock and roll fame or the debauchery of his bandmates, and this is the Platonic ideal of a rock and roll groove. Unless it's this. Or maybe this.

He liked to play a little behind the beat, and there are small disagreements as to how and why that might have come to be, which may be one of the only things we'll ever disagree on vis-à-vis CHARLIE WATTS of the ROLLING STONES, who died Tuesday at age 80, bringing to an end one of the greatest careers rock ever witnessed, if not bringing to an end rock itself. Unlike most drummers, who everyone else in the band automatically follows, Watts tended to follow the lead of rhythm guitarist KEITH RICHARDS, leaving him maybe a hundredth of a second behind in the process, according to the New York Times' BEN SISARIO, whose source is Richards biographer VICTOR BOCKRIS, who got it from BILL WYMAN, who's in a position to know. Rolling Stone's (the magazine, not the band) ROB SHEFFIELD, on the other hand, says the rest of the band actually spent much of its time following and trying to keep up with Watts. "There are entire Stones albums — BLACK AND BLUE comes to mind, so does EMOTIONAL RESCUE — where the concept is the Stones just listening to Charlie play," Sheffield writes. That's a good sentence and a good concept. But who really followed who?

I'd like think the answer to this minor contradiction is: Yes. Because the point is everyone was listening to everyone and Charlie Watts was always somewhere in the middle, the heart of rock and roll beating politely but determinedly behind a small, bare-bones drumkit that he declined to upgrade over the course of nearly 60 years, swinging a rhythm and blues groove, or maybe playing syncopated disco. He was self-taught and had a variety of quirks that every drummer who tried to copy him messed up in some way or another, such as his habit of never playing the snare and hi-hat at the same time, which he said he didn't even know he was doing until sometime in the 1980s. My favorite Watts memorial tweet came from DEERHOOF's GREG SAUNIER, who summed up much of this information thusly: "o to listen that intently to my bandmates and that little to myself."

He would've rather been listening to jazz, though, which almost certainly explains where the swing came from (and provides one more reason why most of his copycats came up short). He never had much interest in playing repetitive rock songs ("the regularity of it" is how he once described it) to screaming fans in arenas and stadiums. "I've always had this illusion," he said in 1996, "of being in the BLUE NOTE or BIRDLAND with CHARLIE PARKER in front of me. It didn’t sound like that, but that was the illusion I had." He used his downtime from the Stones—in later years there was a lot of that—to play in jazz bands of his own design, with some stellar players. That may have been where he was happiest. And most at ease. I read accounts Tuesday of Watts wandering through London record stores alone, with no entourage or fuss, and casually setting up his own drumkit in New York. A musician at work. Which is all he ever wanted to be and all, in the end, he was.

MusicSET: "Charlie Watts Was the Swinging Backbeat of Rock and Roll. All of It."