A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, the Galactic Empire devised a strategy with which they could crush the Rebel Alliance for good. The idea? A space-based battlestation the size of a small moon that had the power to destroy a planet in a single shot. The Empire believed that by using through a super weapon of immense scale and power (the “Death Star”), they could overwhelm the barbarians’ horde of modest rebel fighters or at the very least intimidate them into surrender.

But there was a fatal flaw in this design: a “thermal exhaust port” with direct access to the Death Star’s reactor core. And thus, the epic superweapon was felled by a pair of proton torpedoes delivered by a single, nimble X-Wing at the tip of a swarm of rebel fighters.

The resulting explosion cost the lives of millions, including much of the engineering and non-executive leadership teams. Many of the senior officials that survived the blast (only because they’d been elsewhere) were quickly executed.

The Empire, however, was not deterred. The problem was not the talent, nor the strategy, nor the weakpoint. The Empire decided the Death Star simply wasn’t big enough. So work quickly commenced on the “Death Star II”, which would be the size of a large, not small moon. Unfortunately, however, this second iteration had a shared flaw. The second Death Star required an adjacent planet to support its shields – and thus when the shields dropped (or when the space station was mobile), it was exposed to enemy attacks. Such attacks were harder this time around – they required traveling into the station core, not just shooting in its direction – but access ways remained. And thus, like, the first Death Star, the Death Star II was promptly destroyed. Along with all senior leadership and the Empire’s balance sheet.

More than twenty years passed before the Empire (now the “New Order”) made another pass at a superweapon. But this time, it wouldn’t be the size of a moon, but a planet. And a large one, at that. Unfortunately, the outcome ended the same.

Right Now, In our Galaxy

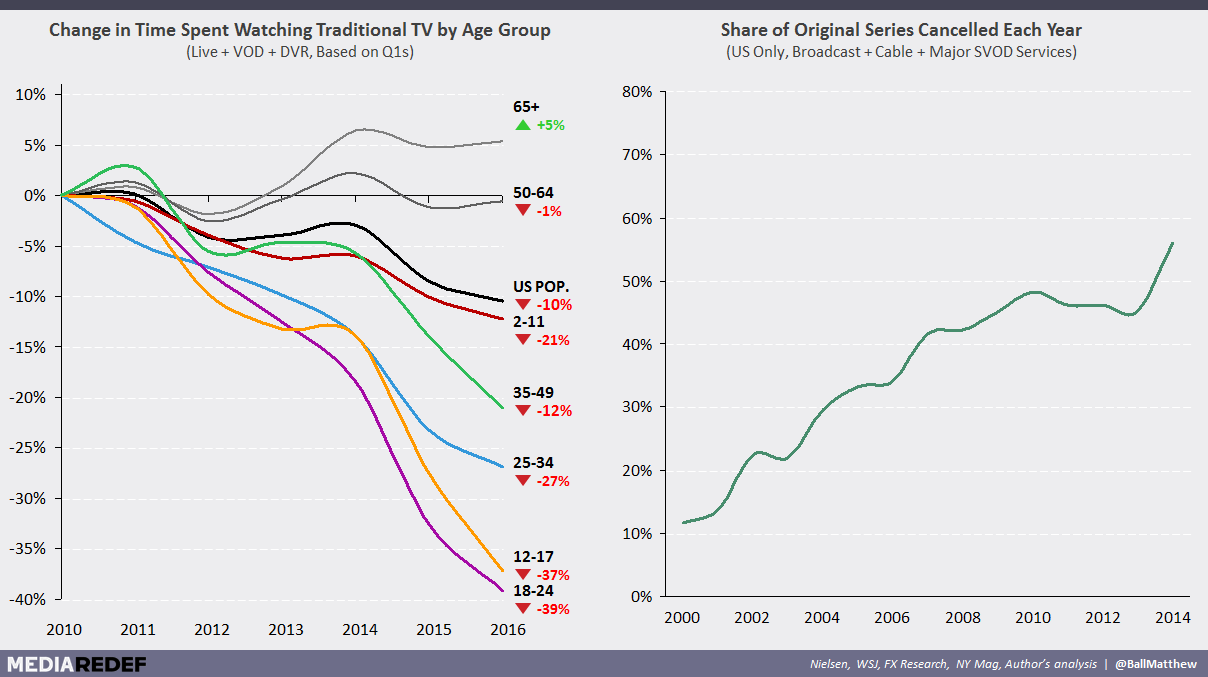

Today, Big Media is having its Death Star moment. The major conglomerates find themselves attacked by scores of small digital media brands, independent (or D2C) creatives and new content formats that are slowly picking away at their dominance and scale. Despite this, Big Media is mostly focused on doing what they’ve always done, just bigger and allegedly better. This means higher budgets, more “premium” content, “premium-er” content, more original programming, higher affiliate fees to offset subscriber declines, more (and longer lasting and more expensive) sports deals, more reboots and so on. There have been no real shake-ups to the status quo, nothing truly different, no real re-imagining of what a network should look like in the digital era, almost no meaningful experimentation in new content formats. And the results have been rough: most of the major media giants have seen massive erosions in their attention footprints, original series are being cancelled at unprecedented rates, and TV engagement is plummeting. Many of the aforementioned strategies have helped stem the decline, but they won’t guarantee a future. Making good – or even great – content isn’t enough.

At REDEF, we’ve said a lot about what to do and why, but responses tend to come down to a few arguments:

- Our people, our content, and our IP are the best and unique. They will enable us to thrive in any environment, on any platform, and in any uncertainty

- With an unprecedented number of buyers, the market for great content has never been more viable

- Our ability to act is limited by the fact that we’re a public company

This first defense, though extremely common, is strategically unconstructive (and impossible for the industry as a whole). Each company has its own advantages in each of these areas, but they won’t insulate them from the broader shifts in market dynamics (i.e. winner takes all competition, the commoditization of units of content, rising costs and failure rates etc.). Moreover, self-confidence is important, but the belief in one’s own exceptionalism rarely leads to success, particularly during periods of tremendous change. At the same time, it’s imperative that media companies invest in their most exceptional talent. The proof here is Viacom[Disclosure 1]. The company’s (former) employees are clear leaders in digital media, perhaps more so than any other conglomerate – we have Judy McGrath (Board of Amazon, Founder of Astronauts Wanted), Van Toffler (Co-Founder and CEO of Gunpowder & Sky[Disclosure 2]), Courtney Holt (CEO of Maker), Susanne Daniels (Head of Original Series at YouTube), Michael Bloom (President of First Look Media), Tom Freston (Vice), Jason Hirschhorn[Disclosure 1] (MySpace, Sling Media), Jeff Lucas (Snapchat), De Juan Wilson (SoundCloud), Fred Seibert (Frederator, Next New Networks), Brian Wright (Netflix) and on and on. One can debate how incomparable this list is, but what matters is that these individuals wanted to do new things in the digital media space and didn’t feel Viacom was the place to do it. Any company that wants to thrive has to make sure that their own feel that they can take digital risks internally.

Though the core logic of the “many buyers” argument seems sensible, it assumes that digital video distribution will play out in a manner similar to TV. While there will indeed be countless different video services, it won’t be a field of relative equals. In digital, scale and enterprise value tend to be distributed by power laws: Facebook is exponentially more valuable than Twitter, Uber v. Lyft, Spotify v. Pandora, Airbnb v. HomeAway etc. This is in stark contrast to the Pay TV model, which supports NBCUniversal, Time Warner, Disney, Viacom, Discovery etc. at relatively equal levels. The reasons for this are manifold, but the consequence is that focusing on the number of buyers overlooks the fact that there’s unlikely to be many buyers at scale and they’ll have immense negotiating leverage. The smaller players, meanwhile, have significantly reduced ability to pay. Even if these dynamics don’t fully play out, the only certainty is that the status quo is coming to an end and that the future is unlikely to be so kind to so many.

The third argument is simply a poor excuse. Big Media CEOs are paid tens of millions each year not to ‘mind the store’, but to make hard, decisive decisions on the future. These choices are more important now than they have been for decades. If public shareholders (or expectations) are the problem, CEOs need to confront them, admit the challenges in front of them along with the pain and cannibalization they’re going to embrace and articulate how they’re going to lead into the future rather than manage through the end. This will cause a share sell-off – but after stabilizing, each media company will have replaced their shareholder base with investors who understand what they’re getting into. Over the past 20 years, television networks have reaped more than $1T inflation adjusted revenues and $300B in net cash flow thanks to what was sown throughout the 1980s and early 1990s (most cable networks took years to hit cumulative net profits, with several market leaders accumulating hundreds of millions in losses doing so). But the harvest is coming to an end. It’s time to rotate and replant the crops.

A Requiem for Alderaan

For decades, Big Media’s playbook has been reliable, remunerative, and routine. When it changed, it did so incrementally (now it’s advertising plus fees!) and during times of constrained supply, stable economics, and slow rates of change. But this no longer works. It’s time to stop rebuilding the Death Star. Imagine if, rather than investing in the space station, the Empire had built countless Star Destroyers – all of which were shown to be nimble, powerful, and adept at guerrilla warfare. Scale, of course, still matters (perhaps more so than ever before), but scale can come in many different ways – few of which will look like those of old. In fact, such a structure is likely a disadvantage in today’s ecosystem.

Enacting this change likely requires new talent, new organizational structures, and reimagined P&L’s. If you look at most media companies, their exec teams are populated by those with development backgrounds, their organizations are built to maximize value in an aging ecosystem, and their P&L’s match the incentives of a previous reality. But is that what Big Media needs to lead in the digital era? The Rebels think otherwise.