As any middle child will tell you, attention – positive or negative – is what really matters. And nowhere is this more true than in the media business. CPM, RPM, ARPU, EBITDA, rating point, MAU, share of wallet – each of these metrics provide insight into a media company’s performance, but the most important and valuable is the ability to grab a viewer’s attention and then keep it for as long as possible. It’s this goal that makes branding, scheduling, “block building”, lead-ins, lead-outs, and franchises so important. Done properly, they enable a distributor to become far more than a 30-minute or hour-long break. Instead, it becomes a content “feed” that serves its viewers with hours of nonstop entertainment. If attention is the media industry’s currency, feeds are its mint. And the bigger the feed, the better:

As a feed scales, it enters a virtuous cycle of success. Audiences bring advertisers and creatives, viewer stickiness brings leverage over both distributors and content suppliers, and perhaps most significantly, programming gets easier. In the television business, a new series doesn’t have to be outstanding in order to succeed if it launches on a popular network – just good enough to retain lead-in viewers (there’s a reason why the most valuable real estate in the business is the Super Bowl lead-out slot). What’s more, audiences can always be supported through on-network promotion, back-door pilots and crossovers. Conversely, television networks with limited attention can struggle to make even their marquee series a modest success story.

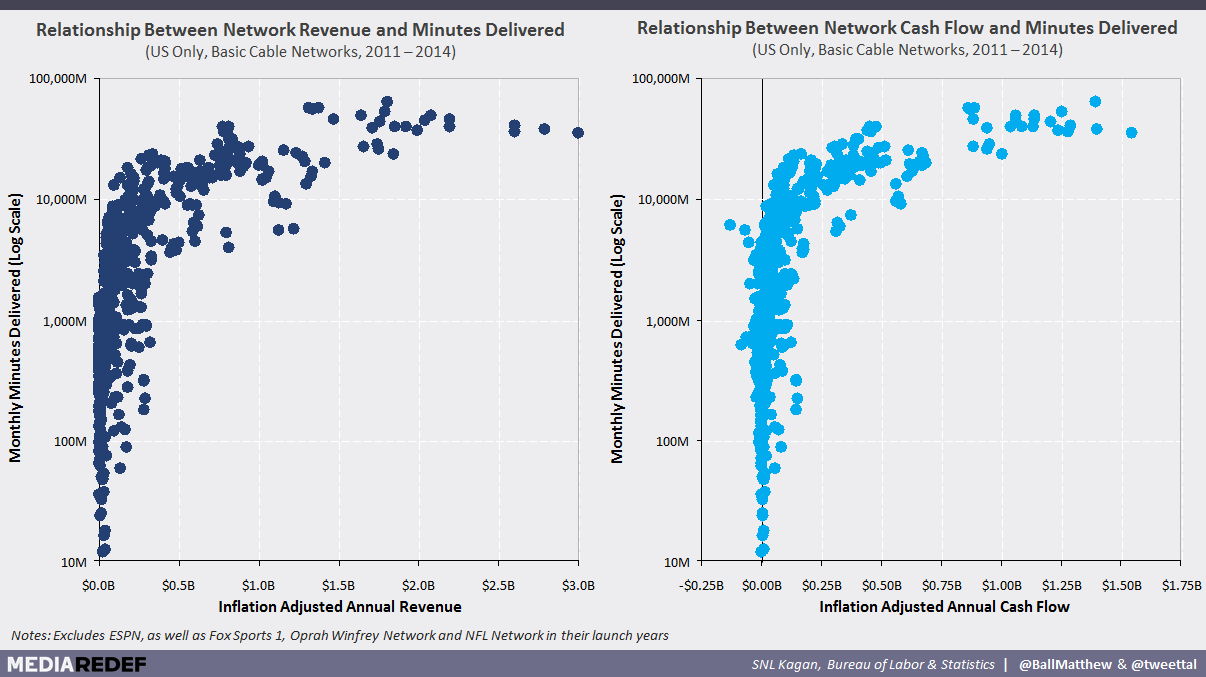

In television, the power of the feed has manifested in several ways. While the traditional studio business of financing content production has been cost-plus or break-even for years, the cable network business has more than doubled topline revenues since 2005 and expanded cash flow margins by 10% (375 net bps). At the same time, MVPDs have seen the portion of Pay TV service revenues paid out to television networks swell from 50% to more than two thirds. Similarly, the persistence of bulky channel packaging and failure of network blackouts as an MVPD negotiating strategy have proven that consumers aren’t interested in access to “television entertainment”. They’re interested in access to specific television feeds.

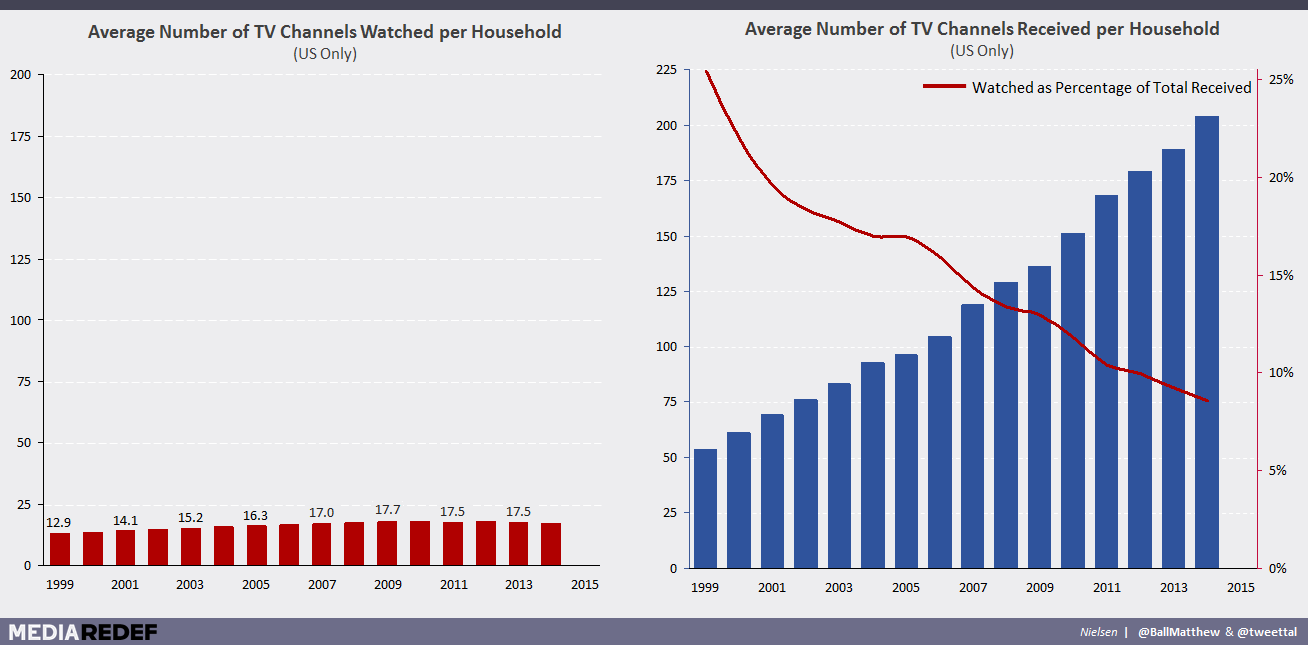

The channel proliferation of the 1990s and 2000s also demonstrated that most viewers aren’t looking to watch more than a few feeds. Even though the average home receives 200+ channels today, compared to fewer than 50 at the turn of the millennium, the average household – not average viewer, average household – watches only four more. In fact, the doubling from 100 to 200 channels saw exactly no growth in the number of channels regularly viewed. Most consumers hook up to a handful of video feeds and do little more than lean back. For more than 150 hours a month.

At its core, the success, resiliency and profits of the Pay TV business itself stems from the fact that cable is essentially a feed. By offering consolidated, single-input access to all television networks, MVPDs ensure that consumers can change feeds with the mere click of a button and almost no interruption in the consumption experience.

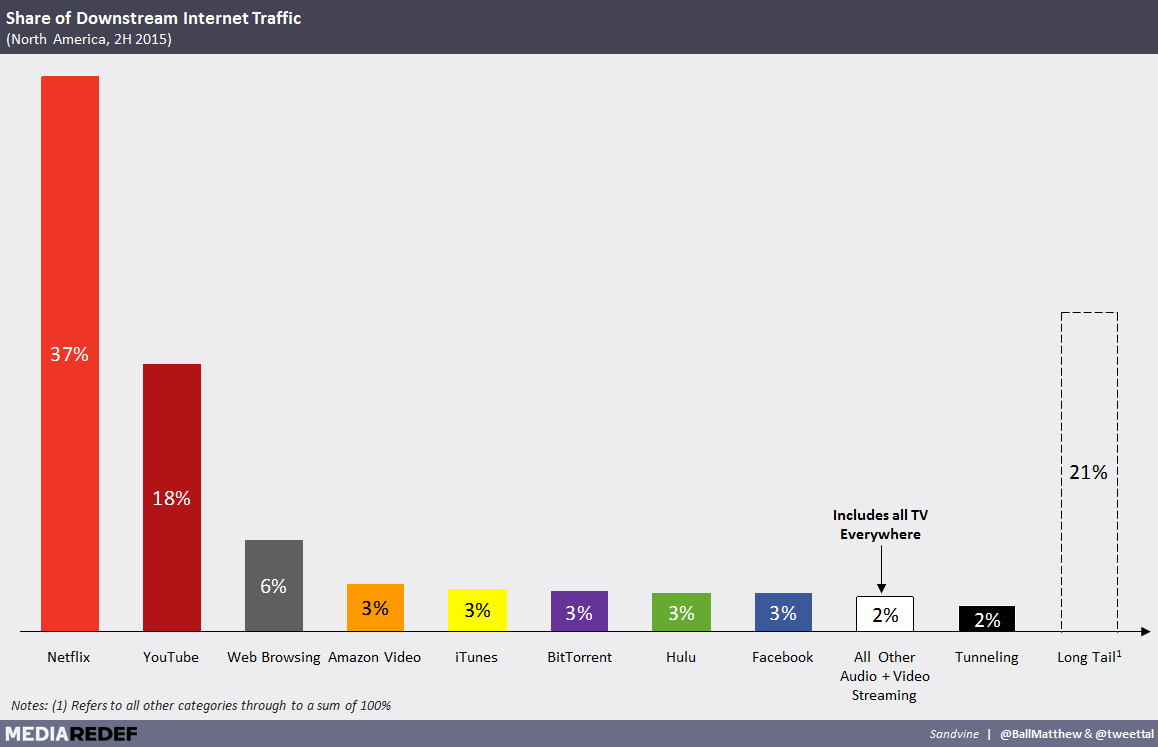

Yet, just like the child who wakes up one day to find themselves with a new, younger sibling, traditional media companies are facing the emergence of new, louder, and needier competitors for attention. Netflix, YouTube, the major social networks, and scores of new digital brands may have started small, but they’re quickly becoming the dominant feeds in the lives of tens of millions. And it shows:

For nearly a century, the American public increased its television consumption year, after year, after year – creating the most important and potent feed the media business has ever seen. But the Great Dismantling is now underway. Over the past five years, the amount of time Americans age 18–24 spend watching traditional TV (inclusive of live, VOD and DVR) plummeted more than 38% (or 41 fewer hours per month). For 12–17s, TV time is down 34% (or 37 hours). 25–34s are down 27% (or 34 hours). Just as cable feed dynamics meant that every additional minute watched made the next minute easier to acquire, each minute lost has and will continue to lubricate the next. Furthermore, rampant multi-tasking has marginalized much of the time that still remains. For millions, the television has actually become the “second screen” experience – it’s the mobile phone that most engrosses during the likes of The Voice, The Walking Dead, and Empire.

The end of traditional television has begun. That much is clear. And even if authentication is figured out, TV Everywhere isn’t the answer. The future of video will look, behave, be valued and interacted with very differently than it has in the past. It won’t just be a digital adaption of linear, and it won’t just be more Netflixes.

Specifically, we believe there will be three dominant types of video feeds:

- Scale Feeds

- Social Feeds

- Identity Feeds

Though these three models will be fundamentally dissimilar, each will be more ubiquitous, absorbing, and personal than the television feeds of old. This has profound consequences for the media business – and in particular, today’s media giants.

MODEL #1: THE SCALE FEED

What It Is:

Among the three models, the scale feed will be the spiritual successor to today’s TV experience, though it will feel more like Pay TV overall than any single Pay TV network. Scale feeds will aggregate tremendous amounts of content of all types (original and licensed, short form and long form, indie and mainstream, comedy and documentary, etc.) and serve as the dominant entertainment destination for tens of millions.

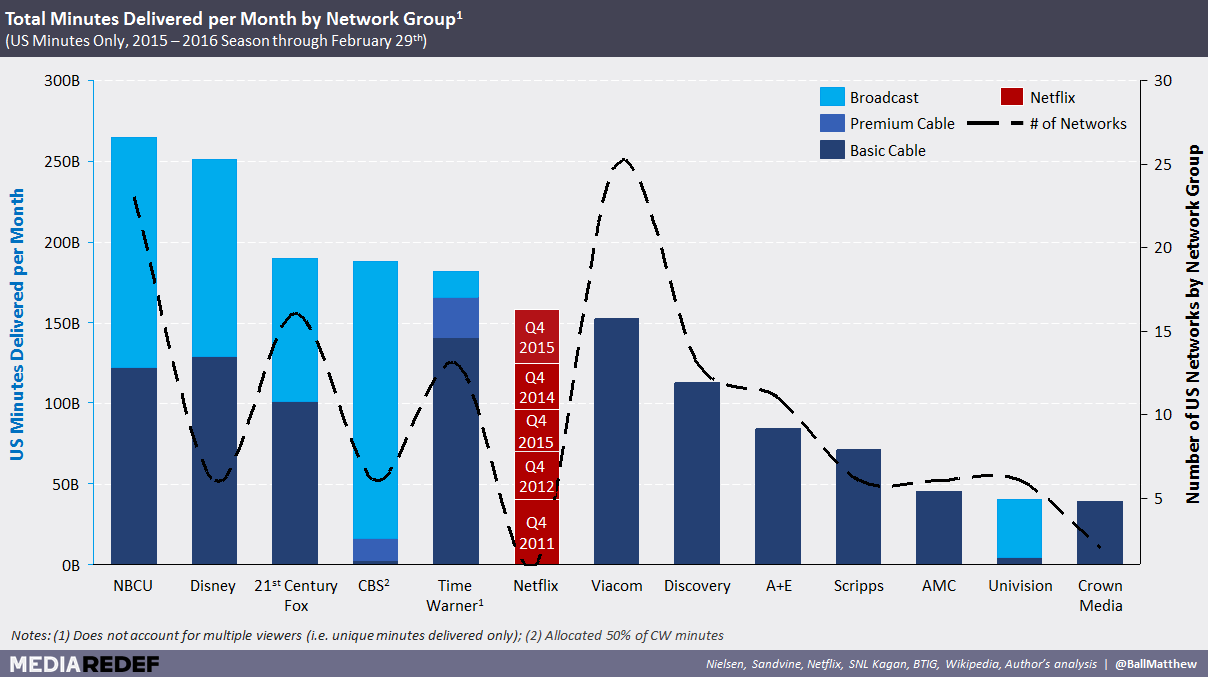

Netflix, of course, is the leading example here. The streaming site counts nearly 45M subscriptions in the United States alone (making it just under half the size of the Pay TV ecosystem), and the average account watches an astounding two hours of content each day (making it not just the most watched television “network”, but larger than any television group’s consolidated cable portfolio). Key to achieving this scale is the ability to “be all things to all people” – an experience that depends on both an immense library and robust personalization capabilities. Finally, scale feeds need to move beyond their country of origin and pursue audiences around the globe. Each added market may require new licenses, but they enable significantly higher investments in (and returns on) software, regional infrastructure, and market-specific original content, as well as increased buyer power. As we’ll explain later, this last point is critical.

How it Works:

The scale feed operating model will be highly distinct from those of today’s television networks. Traditional TV licensing deals, for one, tend to have discrete and self-contained profit models. A programmer has a relatively objective sense what a timeslot is worth, as well as how much ad revenue a slotted series pulls in and what it costs. Conversely, scale feeds will have a much broader and less binary licensing arithmetic. While the primary input will be cost-per-minute watched (Netflix’s favorite KPI), decisions will be informed by softer engagement metrics, such as the pace of viewer consumption (how quickly a season was watched), whether viewing was correlated with reduced churn and/or increased consumption, and how it affected subscriber additions. For this reason – and, as Amazon Studios Head Roy Price is fond of saying – the shift to on-demand video networks means that a series that 80% of people like is likely to be less valuable than one 30% people love (illustratively speaking).

This has several consequences, each of which challenges the traditional “hits-driven” programming model. First, not all licenses will be directly profitable. Second, even the most successful and important titles may drive no incremental business value. Similarly, the genre, type, and amount of content licensed or developed will no longer come down to specific known quantities like time slot availability, “season length”, or individual channel priorities. Rather than program around a defined weekly primetime schedule or try to optimize for the audiences of multiple networks (e.g., Syfy, USA, and NBC), a scale feed (e.g., NBCUniversal) would optimize for their subscribers’ relative interests across all content genres (e.g., science fiction v. drama v. comedy, etc.), as well as their overall appetite for video content.

This last point gets to the model’s biggest departure. While the programming decisions of linear television networks inevitably capped their addressable audience (i.e., if you run a reality series at 8–9 pm, you’re unlikely to get those who hate reality series), scale feeds can and must target all video lovers. Nowhere is this made clearer than with Netflix’s Originals. “There’s some overlap [between audiences of Netflix’s originals],” Netflix’s VP of Original Programming told The Hollywood Reporter last year, “but surprisingly little. We have several series that have been pretty successful, and when that happens there’s a natural overlap. But as a general rule, the audience who watches House of Cards does not watch Hemlock Grove — and yet again, is not the audience that watches Arrested Development. We hope to reach the entire subscriber base with at least one original series by the time we’re done.”

Imagine a traditional network boasting of their audience “underlap”. In a linear environment, this seemingly schizophrenic strategy would actually erode the feed experience and undermine all scale-related advantages. What’s more, scale feeds must pursue audiences across not just different content categories, but also age groups. Thanks to its ability to reduce subscriber churn, children’s content is particularly important. After all, how many parents would consider nixing their kids’ favorite network – especially one they themselves enjoy? “While Netflix will get more attention from adult series such as House of Cards and Arrested Development,” Netflix Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos told USA Today in 2014, “the kids arena is incredibly strategic to us.” In fact, this category is so important that it receives not only its own dedicated section and interface on Netflix, but an exemption from the company’s much-marketed binge release model. Furthermore, Netflix’s single largest original content investment to date was not House of Cards or even Marco Polo – but 300 hours of brand-new cartoons from DreamWorks Animation. Notably, the investment was not an “output deal”, but one where the two parties “work together [to determine] what the [content] will be,” with data-based-performance likely at the core of the partnership.

Finally (and perhaps most positively), customer value will become substantially simpler under the scale feed model. In the Pay TV business, 18–34 year old viewers are far more valuable than those over the age of 50 – so much so that a senior citizen watching American Idol might generate literally no incremental value. In a subscription environment, it doesn’t matter if the customer is a teenager, her mother, or her grandmother (just ask Les Moonves if he cares who pays $5.99 for CBS All Access – or even Philippe Dauman with Nickelodeon’s Noggin’). And on the ad front, targeted advertising and integrated buy buttons stand to bolster (and likely converge) CPMs across age brackets.

How to Establish a Scale Feed:

The existing television giants are actually far better positioned to compete as a scale feed (or “Netflix competitor”) than most believe. To do so, however, they’ll need to collapse their network portfolio model into consolidated offerings – NBCUniversal, rather than NBC, USA, SyFy, Brave, Oxygen, Esquire, Chiller, and so on. Or Fox, rather than FOX, FX, FXX, FXM, Fox Life, Fox Deportes, and National Geographic (with a potential of a consolidated Fox Sports add-on, too). In doing so, each “network group” will be able to maximize the fullest extent of their content, avoid unfavorable price/value comparisons to Netflix, and create the best overall experience for their audiences. Trying to reach effective scale through dozens of independent video apps just won’t work.

Though overdue, some of the major groups are making headway on this front. Fox has already collapsed the apps for FX, FXX, and FXM, while FSGO consolidated Fox Sports 1, Fox Sports 2, and Fox College Sports. Late last year, Discovery also consolidated nine of its 13 networks into a single TV Everywhere Discovery app and HBO began broadening their own offering through a first-run deal with Sesame Workshop.

Notably, however, these major network groups are on very unequal footing. Some, such as NBCU and Time Warner, offer broad and highly scaled offerings, while many of the remaining candidates have far more concentrated audiences, singular programming and modest libraries. While this enables other distribution opportunities, it can be limiting from a scale feed perspective; though Netflix has demonstrated that it can take only a few years to diversify original and licensed programming with concentrated effort. Regardless, time is running out. Interestingly, broadcast (which has been the industry’s whipping boy for years) may end up being a strategically invaluable springboard for aspiring scale feed owners thanks to its large content catalogue and audience footprint.

It’s important to note, too, that Hulu is attempting something even more significant: a consolidated scale feed that cuts across and is owned by multiple network groups (Disney, Fox, and NBCUniversal). This would allow the Hollywood conglomerates to not just recreate the Pay TV feed, but to do so under a model where they own both the content and distribution. This, of course, requires tremendous co-ordination across competitor-partners – as well as a commitment to supplying content and funding a capital-intensive business whose success could cannibalize the Pay TV ecosystem itself (and to varying degrees across owners). Notably, the co-owners are obligated to provide only the current seasons of shows that are both produced by their own production company and aired on their broadcast network (and with exceptions, at that). As a result, the service often provides an incomplete (and inconsistently windowed) catalogue of content and often loses out on titles owned by its own backers but nevertheless licensed to its competitors. With 80% of Netflix’s monthly price, 22% of its subscriber count, and only 7% of its watch time, it’s clear Hulu needs to bolster its content value proposition. The service’s reported plans to bring Time Warner on as an equal-share partner should help (not to mention the related $2B injection). However, the company is allegedly pushing to remove current-season content (the service’s primary differentiator) in order to stem Pay TV cord cutting.

Irrespective of strategic and executional excellence, scaling up to Netflix will still be incredibly expensive and error-filled. Hollywood may be more experienced in content development and distribution, but Netflix benefits from a huge data advantage. Imagine if you wanted to recreate Netflix tomorrow. Even if you were willing to spend the requisite billions on (available) content licenses, how would you know what to buy? How much to pay for it? How long to license it for? This is not only a serious challenge — it’s one that will take several years to get right.

Naturally, scale feeds will also require substantial scale to generate a profit. With 45M US users, Netflix achieves only an 18% domestic gross margin on its streaming business (and that’s after corporate allocations to the company’s 30M international subscribers). Cable, meanwhile, has long enjoyed 35–40% cash flow margins and is relied upon for more than half of all Hollywood profits. Building a scale feed competitor will likely be even more expensive now than it was for Netflix, and as such, likely require even greater scale to reach profitability.

This margin hurdle speaks to the necessity of international expansion – though this imperative will only exacerbate short-term pain for today’s traditional leaders. For most content producers or rights holders, international sales have been an enduring source of high-margin gravy revenue, where virtually nothing is risked or incurred other than the few employees needed to cut deals. Granted, digital distribution is far less expensive and complex than standing up a new linear network abroad. Even still, establishing a foreign OTT service will require extensive marketing and localization efforts, regional infrastructure, new licensing, and so on. As a result, scaling a feed outside traditional borders will require both significant capital outlays and the sacrifice of presently lucrative revenue streams. But as Sarandos told the Television Critics Association in January, “The profitability [of Netflix] is mostly driven on our international expansion space, not on the content.”

Sadly, the major networks will also need to forgo domestic revenues too – if not dig back into their pockets. For years, the major network groups have readily licensed their content catalogue exclusively to the major SVOD platforms. Fox’s Empire and Gotham (the network’s 1st and 3rd highest rated original scripted primetime series during the 2014 – 2015 season) have been licensed to Hulu and Netflix through to the end of their runs, with NBC’s top original, Blacklist, also committed throughout its run. As a result, the major network groups will either need to buy back rights or commit to numerous additional series that will only be available through their own O&O platform (as CBS is doing with their new Star Trek series).

What the Risk is:

Most of today’s media companies think they’re going to be scale feeds. But they won’t.

One of the more under-recognized perks of the traditional Pay TV model is the fact that no network group can “own” the entirety of a household’s video time or spend. No subscriber, after all, can order only Viacom networks or just Time Warner channels – no matter the package, price, or tier. As a result, each of the major network groups profits from every Pay TV subscriber (via affiliate fees) and benefits from the fact that their channels can be watched without that subscriber needing to call their cable company or enter their credit card. If they do watch the channel, there’s added upside of course (ad revenue + added affiliate negotiating power), but carriage guarantees long-term distribution, discoverability and viewership.

Online, however, this communitarian utopia will be replaced by a whole new competitive dynamic – one that challenges the idea of “shared” or “in-common” subscribers and makes it harder than ever to acquire new ones.

The average Pay TV household watched roughly 300 unique hours of television each month during the 2015 – 2016 season-to-date, spread across only 17.5 of the roughly 200 channels they received. Given the surplus of content available and the breadth of content offered by each of the major network groups (which count one-to-two dozen or more 24-hour channels each), many households will likely find they need only two to three consolidated offerings to meet their video needs. What’s more, the friction involved in paying for and managing multiple apps will give subscribers an incentive to watch more of the content they’ve already paid for instead of adding a third or fourth scale feed for another $10 or $20 a pop. How many Netflixes, after all, does the average person need?

These dynamics will give the early market leaders a significant competitive advantage and create considerable barriers to late entrants and modestly sized competitors. How does a sub-scale scale feed acquire new customers or set price, given their comparatively smaller library? How does any feed convince a would-be subscriber to abandon a service they’ve already invested hundreds of hours in to try another? Is one stellar show enough? Are three? And even then, how does one ensure ongoing subscriptions, rather than single-month content binges? How does relative scale affect a feed’s ability to compete for content or creators? How do they outbid competitors with much larger subscriber bases and much greater usage for top titles? And as Netflix CEO Reed Hastings likes to boast, the company’s ability to buy global rights means that it doesn’t need to be the highest (effective) bidder for US rights to seal the deal. With the service available in more than 200 countries (including Cuba, Kuwait, and Kenya), Netflix can also significantly outbid its competitors and still make a profit. In aggregate, these challenges culminate in the television industry’s most intractable problem: power laws.

So far, digital-era “value” follows a power-law distribution. Facebook (with a market capitalization of $310B) is exponentially more valuable than runner-up social networks (LinkedIn at $15B, Twitter $12B and Snapchat $16B), just as Uber (~$65B) is to Lyft (~$5B), Airbnb (~$25B) is to HomeAway (~$4B), and Spotify ($10B+) is to Pandora ($2B) and Netflix ($45B) is to Hulu ($5B). While a few traditional television groups may succeed in becoming scale feeds, they may still find themselves disappointed with the results. Unlike today, in which there are a handful of different media groups of relatively equal value relative to their footprint, the future will be winner takes most. Just look at Netflix ($45B) to Hulu ($5B).

This gets to an existential point. If the network model goes away and content windows collapse[1], every content company is essentially in the SVOD licensing business. The only real question, then, is whether they license to their own SVOD service (making the company vertically integrated) or a 3rd party one. But if scale feeds operate according to power laws (with respect to both audience and profits), many of these companies would be better off simply re-licensing their content to the highest outside bidder. End-to-end distribution, after all, would result in significant cost increases and only marginally greater revenues (and, very possibly, lower revenues too). However, that doesn’t mean that being a scale-feed content supplier will be a lucrative business…

What Happens If You Don’t Own a Scale Feed?

The scale feeds of tomorrow will be far more powerful than the dominant video feed owners of today. Not only will they be bigger and more influential, they’ll also be more rare – which means life as a content producer will inevitably become less profitable and stable than it is today. Without feed ownership, independent content companies are relegated to an input – and a highly modularized one at that. Knockout television series (such as Game of Thrones) will remain extremely valuable, of course, but virtually all other content will become a commodity. Consider the following from Netflix’s “Top Investor Questions” page:

Q: How do you evaluate new content deals or renewals?

We utilize detailed statistical models to determine expected hours of viewing for each piece of content over its license period. We compare cost per hour viewed against other “like” content deals (i.e. exclusive versus non-exclusive, TV versus movies, etc.). We look for high engagement and cost efficiency. For renewals, we look to renew content that performs well (based on hours generated relative to the cost) and do not renew content where the price doesn’t make sense relative to the value generated. We feel we have good breadth of content so that no specific title or set of titles is must-renew.

This advantage comes from several structural changes to the video market; each of which disadvantages suppliers. First, we’re not just in an age of content oversupply, we’re in one where video content is much easier and cheaper to produce than at any other time in history. As a result, those with histories in video content production and access to capital have lost much of their effective monopoly on high-quality programming. In addition, services like Twitch, YouTube and Vine have shown that so-called “premium” or “produced” content has no inherent advantage over supposedly simpler forms of video entertainment. And although power laws suggest scale feeds will be able to pay more than almost any other buyer in history, that doesn’t means they’ll pay a “high” price. In fact, it makes a bargain all the more likely.

Core to the supplier-scale feed negotiating imbalance is not just relative size, but also immense information asymmetry. In most instances, scale feeds will have a far more accurate view to historical and/or likely title value than the actual right-holders themselves – especially when compared to other investments (i.e., the feed’s alternatives). Is the license coming to an end? A scale feed can algorithmically push the title six months early to maximize value, and then pull back on recommendations to ensure that users don’t miss it when it’s gone. Making matters worse is the fact that OTT subscriber dynamics (as described above) will make transitioning audiences across services profoundly difficult. If a licensor opts to use a Netflix-built audience to shift content to a smaller-scale feed or owned-and-operated platform, they’ll likely incur a substantial drop in viewers – thereby eroding the very value they sought to capture. And at the end of the day, rights holders are subject to immense disintermediation risk. Last year, Netflix announced a partnership with Silverback films for a sequel to Planet Earth, a much-lauded nature documentary series that was originally produced and distributed by BBC/Discovery, but was particularly popular on Netflix. Not long after, Netflix did the same with Black Mirror. Under the scale feed model, intermediary rights owners add far more cost than they do value.

In this sense, Hulu offers Big Media a unique opportunity. Not only does it substantially bolster their collective odds of establishing a top scale feed (if not the top scale feed), it does so in a manner in which they can all participate. Furthermore, the ownership of both content and distribution should provide added margin and their combined catalogue could enable a material premium compared to other scale feeds. However, if Hulu’s owners see the service as their OTT scale feed future (instead of their own O&O), their commitment needs to be intensified. Instead of contributing only select broadcast content and the occasional cable series, Hulu must become their full-stack, cross-portfolio OTT offering (i.e., all of NBCUniversal, all of Fox). They can’t just be opportunistic or obligation-based contributions. That said, such a model does not eschew the aforementioned scale feed dynamics. Even as a collective, the value of individual contributed titles would be highly commoditized (it’s not hard to imagine a Spotify-style royalty model based on time viewed). Although participants would benefit from both licensing revenue and equity appreciation (again, not unlike Spotify), this value may nevertheless pale in comparison to that of the traditional Pay TV ecosystem.

The challenges of runner-up scale feeds speak to why it’s so important that the television business acts quickly. Not manage traditional TV’s decline or changing customer behaviors. Not build digital revenue streams to offset linear losses. Actively push audiences away from linear and to their digital platforms while their content resonates. It will be rough, but their current shows are the hook. And it will be much easier to establish a scale feed today than trying to regain lost viewers five years down the road.

What about YouTube?

Though distinct, YouTube does represent a scale feed. It has an immense catalogue – with no single title, franchise, or library essential to its overall success – and it boasts a massive audience that consumes tremendous volumes of content each day. Although the service includes many of the most widely viewed videos worldwide, it would be a mistake to view it as a digital-era broadcast platform. Like Netflix, the service succeeds because of its personalization and deep, varied catalogue (which includes both YouTube Gaming, live streaming, and an on-demand music service). In fact, YouTube’s initial content investments failed in large part because it focused on broadly targeted content from traditional mass-market brands. Instead, the company now focuses on funding creators who have built up passionate, but comparatively niche, followings. In addition, the aforementioned scale characteristics also mean that those who create and/or distribute through YouTube face the same dependency and value-capture dynamics of the more conventional scale feeds.

MODEL #2: THE SOCIAL FEED

What It Is:

While scale feeds will be the digital successor to Pay TV distribution, the spiritual successor to the Pay TV feed will be the social networks. What’s more, social feeds like Facebook and Snapchat represent the feed in its most potent iteration to date – bundling together all forms of content: personal and impersonal, photo and video, text and visual and audio, ephemeral and evergreen, etc. And while cable represented a profound leap forward in audience targetability, the social feeds deliver unlimited audience relevance; everything a viewer sees is designed to capture, engage, and retain their attention specifically. Further still, the viewer can go on to discuss and share this content from within the same very feed. The social networks, in effect, bundle content with the water cooler itself – and to great effect. As Ricky Van Veen commented last year, “Facebook is the Internet.”

This capability provides the social platforms with unique and powerful advantages in terms of driving engagement and monetizing attention. This is easily demonstrated by the pace with which each platform has come to rival YouTube, which launched more than a decade ago and is now the most popular video service on the planet.

There are certainly ways to nitpick this consumption to date – it’s not nearly as sticky; it’s much shorter, less valuable, unplanned, and so on. But as Snapchat, Facebook and other regionally dominant social feeds look to further gains in user time and leverage their existing footprints, they’ll undoubtedly pursue more conventional content. And though the exact user experience is a little unclear (if just because the product will rapidly iterate and evolve), the social networks will become an increasingly important distribution platform for most content companies – young and old. Not only will they offer unparalleled targetability and audience intelligence, these services will also inherit the Pay TV industry’s most important attribute: universal reach.

Although consumers often complain that limited MVPD competition resulted in high prices and substandard products, it also protected them from the sort of content-exclusivity race that’s set to wreak havoc on the music streaming business. If you want to watch TNT, you don’t need to drop Comcast and sign up for Charter, for example – nor do you need to give up any channels if you wanted to. Similarly, no content owner needs to go to one provider to reach Gen Xers and another to reach Baby Boomers or Gen Z’s. Just as all content is available through all distributors, all audiences are available through all distributors in a given footprint.

As the OTT video ecosystem develops, however, audiences will become increasingly fragmented and isolated across individual aggregators and O&Os. Not only will broad demographic groups separate, but these segments will also splinter off into smaller groups based on their shared interests. Although scale feeds will be widely consumed, no one provider is likely to achieve Pay TV’s historic 90%. As a result, content creators will find audience development far more difficult (and the cost of changing licensor far worse) than ever before. Crucially, however, the social feeds will continue to reach nearly every consumer – at almost all times of the day and with unparalleled targeting capability. This will make social distribution critical for any content company that’s struggling to reach or build an audience.

Finally, it’s important to distinguish the major social feeds from YouTube, which boasts comparable reach but operates as a scale feed. The difference is demonstrated by priorities. For a scale feed, what matters is driving overall consumption. As a result, YouTube offers liberal embed capabilities that enable the delivery of YouTube content through YouTube’s player but outside of YouTube’s owned-and-operated website. For a social feed, however, off-platform embeds are ultimately undermining. The point of video, after all, is to drive more time in their feeds – not video views themselves. Accordingly, we’re unlikely to see Facebook, Snapchat, and company integrate their video players elsewhere, and we may soon see paid SVOD services enable embeds. If you’re paying for Netflix, should it really matter if you binge the content through Netflix or on, say, Jessica Jones’ official site?

How to Establish a Social Feed:

The short answer is: you can’t. Until a major platform shift occurs, the emergence of a major social feed is extremely unlikely (just ask Google). Fortunately, the best opportunity to steal share comes from a platform shift – and virtual reality, which will be tightly linked to the media business, is likely to be one. But until then, it will be extremely tough for Hollywood to pivot their existing assets into a social feed.

How to Work with a Social Feed:

How to use a social feed comes down to a question of goals. Specifically, whether the content supplier is looking to:

- Build an off-platform (or O&O) audience;

- Increase the popularity of their content such that the corresponding IP/licenses increase in value; and/or

- Craft itself into a socially distributed media company

While these objectives can be pursued and achieved concurrently, how a content owner or rights holder decides to prioritize these three goals will have a significant impact on the economics, operating model, and needs of their business. For objectives one and two, social feeds represent the very top of the funnel, for example. In the case of number three, social feeds are the funnel. And this is what makes establishing clear priorities so important.

Distributing through any feed you don’t own, means modularizing your content, releasing control over the viewer experience, and giving up ownership of the audience. As a result, anyone pursuing the first two options will need to accept that revenues will be low, cannibalization significant, and payback long. While this strategy should be straightforward (the plan is to make the “real money” elsewhere, after all) – most media companies will struggle with the commoditization of their “premium content”, the mismatch of high production costs with low CPMs, and the urge to quick-win license any IP that starts to get traction. But with nearly three quarters of new series cancelled in their first year, it’s shocking that networks still avoid the world’s largest and most popular online content distributors. Uploading your first episode for free access on YouTube isn’t enough.

This argument is most clear with “failed series” – for a struggling show, any lift is critical – but it applies far more broadly. Consider Lifetime’s unexpectedly terrific and criminally under-watched UnREAL. The show, a scripted drama focusing on the behind-the-scenes production of a fictionalized version of The Bachelor (and written by a nine-season veteran of the actual show), is practically engineered for social obsession. Yet through its first season finale in July, the show averaged only 700,000 viewers, which should place it between 150th and 175th among primetime original series during the 2015-2016 season. Since then, the show was essentially TVOD-only until a January 6th deal landed it on Hulu. A sign of success, to be sure, but imagine if the first season had been distributed by Facebook (either during its initial release or after original airing as part of a rapid second window), with behind-the-scenes content and opportunities to interact with the show’s stars and creatives. UnREAL’s first season rights may have been less valuable, but the value of the franchise overall could have become much greater.

It’s equally important to recognize that the rise of influencer curators will make social distribution a uniquely important aspect of finding and developing an audience. As consumers struggle to digest the ever-increasing supply of multi-media content, independent tastemakers will become instrumental in directing their (pre-dominantly social network-based) followers to individual media properties. Accordingly, these influencers have the potential to provide unique awareness and consumption lift, as well as a more nuanced (and symbiotic) approach to social distribution.

Crucially, however, the points above make social distribution a tool – not a business – for traditional media companies. Success will remain too unpredictable and cost structures too high – even if Facebook or Snapchat unveils paid bundles or a la carte offerings. This is where the third type of content supplier comes into play.

A number of companies, including BuzzFeed and AwesomenessTV, have been fundamentally architected for social distribution. They are lean, data savvy, and fixated on the navigation of multiple feeds – determining what content works, how to re-cut it for different platforms, and how to rapidly monetize and proliferate IP. Vice, for example, excels at creating bespoke takes for different platforms, whether it’s Snapchat, YouTube, Facebook, go90, or vice.com. The company is so confident in these capabilities that most of the content on VICE’s forthcoming linear channel will also be freely available on Facebook and vice.com – both before and after launch. The “feed navigator” business model is also unique in that it often includes reselling the companies’ core capability – the creation of socially distributed content that taps into youth consciousness. Rather than just selling “slots of time” that inevitably interrupt the viewing experience, navigators offer in-house branded content studios that weave together digital entertainment and product marketing. Although the line of business remains modest as a percentage of total revenues, it also boasts a strategic advantage: the ability to profitably create and test content IP.

While these content companies are critiqued for their limited revenues and low margins, focusing on the present largely misses the point. What really matters is whether navigators can use their social insight and reach to improve the quality and commercial potential of their content faster than (feedless) Hollywood incumbents can adapt their content and cost structures for the digital era. BuzzFeed, which has set up its own motion pictures group, thinks it can. And as the social networks suck in more time, ad dollars, and content, those able to navigate social feeds will not only become increasingly valuable, their lead in new media will widen.

What the Risk Is:

While social feeds will likely emerge as the best way to boost awareness, engage with fans, and grow audiences in the years to come, challenges will nevertheless remain. Today, Hollywood is mostly concerned with the services’ monetization models and attendant economics. Will Facebook launch an a la carte aggregator like Amazon? Will it stick to a curated selection of brands a la Snapchat? Will there be any minimum guarantees or licenses, or just revenue share? Who will sell ads? What data will be shared? Not only do these questions remain largely unknown today, the answers will constantly change as social-based video distribution proliferates and matures.

But contrary to popular thinking the real challenge here isn’t the monetization model, it’s leverage. What makes Facebook so powerful when it comes to content distribution is that it fundamentally doesn’t care. It doesn’t care which videos a user watches or likes, when and how they watch it, or really, whether they watch video at all. Facebook just cares that its users are on Facebook. The watercooler matters far more than the content. And as one might expect, this will create a serious challenge for any content owner looking to achieve an economic profit through social feed distribution.

Like scale feeds, Facebook can also de-emphasize content coming up on expiration by suppressing related Facebook dialogue (on the nefarious end) or promoting similarly-targeted substitutes (on the other). A social feed, in effect, owns all on-platform content audiences – both potential and actual – and can wean them on or off at will. This illuminates the clear power differential between both scale and social feeds compared today’s TV distributors. The strongest negotiation tactic an MVPD could deploy in the Pay TV era was a channel blackout – cutting the feed, if you will. While this is technically a two-party decision, customers almost exclusively blame the service provider. Content is not only a necessity, but it’s both an MVPD and television network’s most potent differentiator (as NFL Sunday Ticket can attest). Conversely, scale and social feeds can not only absorb the loss of key titles, they can make a star out of an unknown simply by spotlighting their content.

Fundamentally, the media industry has never had to distribute content through a platform that didn’t actually need that content to succeed. The power of Facebook and Snapchat comes from the eyeballs they already own and the social utility they already provide. Their embrace of video distribution comes from the at-hand financial opportunity, not a structural need. If this situation seems dire now, imagine a world where Facebook not only owns its social feed, but through Oculus, the distribution infrastructure as well.

One of the key lingering questions for those considering social distribution is whether these networks will offer a la carte plus bundled content subscriptions – a move that would formalize their role in the content ecosystem, enable content owners to capture more value from social distribution, and position the social networks as digital-era MVPDs. Due to their reach and user data, these offerings will likely succeed and as such, content owners should embrace the attendant opportunity. But despite improved economics, these models mitigate few of the downsides and limitations of social feed dependency. Content providers will still be without a feed, lack leverage over the social network itself, and need to compete with the price-value offered by scale feeds. Similarly, it’s important to understand that the replication of the Pay TV MVPD model does not mean that Pay TV economics will apply. Not only are digital distribution profits likely to be more modest, but they’ll also be distributed across far more content owners.

MODEL #3: IDENTITY FEEDS

What It Is:

Although the ascendance of so-called “niche content” is far from new in 2016, the related content models remain painfully under-characterized. Niche video providers will not just be focused, smaller versions of the scale feeds; they will be fundamentally different in structure, content, and monetization. These services will focus less on delivering video entertainment and more on packaging (or “bundling”) together a variety of related multimedia experiences, including in-person events, merchandise, news, photos, podcasts, essays, and live commentaries. In doing so, these providers will build a community for those who see their “niche” content not as a passing interest, but as a core component of who they are and how they define themselves. Accordingly, not all will center on what we traditionally view as niche genres – many will engage specific sub-cultures, lifestyles, or backgrounds. Despite this variability, these “identity feeds” will demonstrate similar consumption behaviors – their users will constantly (if not reflexively) engage with their multi-media products on a daily basis.

It’s important to stress that identity feeds are not simply built-out vertical content offerings. Although every consumer frequents dozens of brands designed for their very demographic, psychographic or interests, this relationship is rarely meaningful. Regardless of ARPU, promotional newsletter open rates or store visits, few consumers go home and think about their favorite brands, use their patronage as ways to describe their own interests or look to engage with similarly minded shoppers. Even though the consumer-media bond tends to be stronger (a benefit of time-based services), the same applies to content companies. Syfy, for example, is a terrific television network that entertains a central media genre. But how many science fiction fans want to wear (let alone buy) a Syfy t-shirt? Attend a Syfy convention? Or consider the network essential to being a science fiction fan? A true identity feed is a vertical channel merged with a lifestyle brand, fan club and (digital) third place.

Many of today’s top digital video brands – TheBlaze, Crunchyroll[Disclosure], Rooster Teeth[Disclosure], The CHIVE, Ipsy – already succeed through their ability to create comprehensive content experiences that fundamentally connect with their audiences. And as the bundle breaks apart (freeing up both consumer spend and traditional video providers), the video business will experience rapid growth in the number, size, and influence of individual identity feeds.

How it Works:

Life as an identity feed is considerably more complex and (human) capital-intensive than either the Pay TV feed or the emerging scale and social feed alternatives. Most obviously, feed owners will need to produce significantly more types of content than just video – including in-person events. As a result, monetization will also become less straightforward and more varied than that of a “pure” video business. Certain types of content, products, or services will be directly unprofitable, for example, but still essential to overall profitability thanks to their ability to drive engagement and enhance stickiness. For a business used to cutting anything without a straightforward and in-the-black P&L, this will require a fundamentally different corporate culture.

Similarly, customer value will be tremendously skewed towards the most engaged subscribers – those that buy brand-extension products, consume the greatest share of multimedia content, purchase live events tickets, and so on. This, too, represents a critical departure from the traditional TV modus operandi. While not all Pay TV subscribers are of equivalent value today[2], they aren’t individually known, served or valued. As a result, traditional TV audiences are viewed largely homogenously from a monetization perspective. Conversely – and also unlike either scale or social feeds – identity feeds will also adhere to and require a strict user funnel. This will require not just extensive subscriber acquisition capabilities, but also supporting a large AVOD business that adds limited tangible value, but is nevertheless critical to creating and sustaining a large and engaged community. And despite their distributional similarities, the shift from a “hit show” to a “whale customer” will require developing new organizational models, incentives, and priorities.

How to Establish an Identity Feed:

To create an identity feed, media brands must first establish an authentic relationship with the most passionate consumers in their target audience. These users are the most important for brand evangelism, establishing audience credibility and offering refinement/feedback. To do so, an aspiring identity feed must provide a distinct voice – not a unique brand identity, but a culture and feel that appeals to the obsessiveness of the individual fan but still resonates with the community as a whole. Naturally, this can’t just be declared, bought or marketed. It must be earned and developed over time. It’s no coincidence that most of today’s more differentiated and successful digital brands began around the long-incubated voice of individual (and often controversial) founders such as Shane Smith, Ryan Schreiber, or Glenn Beck.

This, of course, presents a foundational challenge for today’s entertainment giants. These companies have traditionally (and appropriately, given the limitations of linear TV) maintained unidirectional audience relationships, firmly reiterated corporate brands, and focused on audience maximization above all else. As a result, they’ve never staffed up or developed the capabilities required to super-serve their core viewers – let alone build their feedback into the creative process. Similarly, few have pursued multi-product monetization models or rapid/user-driven content creation. For young media brands, however, these operating philosophies are native. Most of them moved into additional content categories due to audience demand – and slim OTT margins forced emerging video-focused brands to diversify.

Even still, today’s players have the opportunity to convert many of their existing brands into identity feeds. Fox News, though operated differently, has already built up a robust and focused identity and boasts a passionate audience that consumes scores of Fox News-branded multimedia products. Many Scripps properties, such as HGTV, DIY, and the Food Network, could translate well – as could carve-outs that cut across a conglomerate’s linear channel portfolios – as could a number of current “third tier” networks, such as the World Fishing Network and the Sportsman Channel. Crucially, however, identity feeds are not incompatible with the other feed models. As long as a more focused, multimedia, and voice-driven experience is provided, a media company can still bundle (or sell) portions of an identity feed’s video content into a broader OTT offering or drive awareness through social distribution.

At the same time, identity feeds won’t just be operated by “media companies” as we define them today. After all, what enables these content services to thrive is not the ability to create the most “premium content”, but their ability to understand, appeal to, and resonate with a given audience. Though rare, this skillset is not confined to the media business. It’s often found among personalities like the Kardashians and underscores companies like Bevel, a shaving hardware start-up targeting men of color. How many journalism paywalls or SVOD services lag the Kardashian suite of subscription apps? Is Bevel Code just marketing, or is it an integral part of the experience a Bevel subscriber pays for? Traditionally, individuals and product-based brands had little opportunity to translate their brand into media content – distribution capacity (e.g. broadcast spectrum or linear distribution) was finite, costs of entry were considerable and breakeven revenues were largely unachievable. What’s more, television’s unicast and MVPD-led distribution model prevented these companies from their core focus: identifying and super-serving their core customers. As a result, most of these video plays (e.g. Esquire TV) have barely registered. With customer loyalty at record lows and pricing transparency at record highs, identity-based media marketing represents a brand’s best opportunity to deepen their customer relationships and leverage their audience intelligence. This will only be possible for a handful of brands and individuals, but for those that can, the results will be profound.

What the Risk is:

As any signed musical artist can attest, businesses built around authenticity and a fan’s sense of self are extremely hard to establish, maintain, and especially to grow.

Due to the importance of authenticity and community buy-in, creating a successful identity feed will take time. They can’t just be stood up, no matter how prominent or scaled the backer, or how deep the marketing budget. What’s more, many of the hallmarks and core capabilities of Big Media represent weights, not advantages. Layered management models, brand guidelines and focus group-testing, for example, can easily stifle the creation of a distinct voice or culture. In addition, the ability to drive awareness through mass marketing is of little applicability (and could undermine a subscribers sense that the service was “made for them”) and “premium production” capabilities are likely less valuable than the ability to rapidly create (or pivot) content (in fact, over-production could also undermine a service’s sense of individuality).

On the maintenance front, an identity feed’s reliance on individual voices also exposes them to significant key man risk (see Simmons, Bill). And unlike in the Pay TV business, these singular personalities can easily transition their fame into independent, direct-to-fan properties and identity feeds thanks to digital publishing tools like Medium and Victorious (making ownership stakes a critical component for retaining top talent). At the same time, organizational growth (whether audience-facing or not) poses the inevitable risk of diluting the brand or its voice. Similarly, it could be argued that offering too much content (either to broaden the audience or enhance ARPU) could erode the site’s sense of community – you can’t identify or engage closely with a service that produces far more than you ever see, touch or participate in. In addition, identity feeds will face constant pressures from more targeted (and perhaps user-funded) competitors, as well as those whose business models profit from (or subsidize) different parts of their offering.

Most critically, however, identity feed owners must also contend with modest audience ceilings. Although they may be higher than mass-market media companies believe, all voice-driven or sub-culture communities are limited by a firm (but hard-to-estimate) ceiling beyond which attracting a broader audience would endanger the core. This doesn’t preclude meaningful per-user revenues, but it nevertheless caps revenue potential and scale-dependent initiatives. The best a conglomerate can hope for is a constellation of individual identity feeds that are supported by shared back-office and events functions.

MODEL #4: What about Video Services that Don’t Own a Feed?

Scale, social, and community feeds won’t be the only models for consumer-facing digital video providers in the years to come. The future will include scores of independent video services that entertain small-to-moderate audiences and extract meaningful value from doing so. The problem is that they won’t be particularly valuable unless they own a “feed”. Without it, growth will be difficult, audiences fluid, and economics modest, thanks to unfavorable market dynamics and price/value comparisons. Profit will, by and large, be limited to content license arbitrage.

… AND THAT’S A WRAP

If you were in it, the old television model was a godsend. Anyone with channel space could establish a feed and those that failed (or arrived too late) had the luxury of falling back on the feed-like Pay TV experience. What’s more, Pay TV dynamics meant that all customers were shared, just as easily found as they were lost, and participation ensured both years of locked-in revenue. Online will work very differently. Mass entertainment will shift to winner takes most, with the largest services monopolizing profits and social networks controlling the destiny of much of the remainder. There will be dozens of successful niche video distributors, but only those able to establish passionate, multi-media audience communities will realize significant value.

If the major media conglomerates are unable to succeed with the aforementioned over-the-top offerings, they will, according to them, thrive through competition between competing content buyers. Unfortunately, this view overestimates the likely number of sustainable long-term distributors and underestimates concentration of power. As a result, most will find their content modularized, relegated to simple inputs for those who do own a feed – which will make cost cutting, long Hollywood’s neglected half of the profit equation, crucial. As the American newspaper industry faced the decline of its own “feed” – an editorial bundle that carried attention from national news through to sports and crosswords – revenues dropped by more than 50% and expenses became the dominant profit lever. Thanks to still-significant production barriers and a greater share of consumer time, the video business will fare much better than print, but those banking on a lucrative sequel to Pay TV will find only disappointment.

“After TV: Video’s Future will be Bigger, more Diverse & Precarious than its Past” is the second of a three-part series on the future of video and Hollywood. Part one,”TV Has a Business Model Problem. And It’s Killing Good TV”, can be found here. Part three, “By Obsessing Over the Present, Big Media has Forgotten its Past and Endangered its Future”, can be found here.

Matthew Ball is a Director of Strategy & Business Development at Otter Media and leads Strategy & Originals at REDEF.

NOTES:

[1] It doesn’t really matter how content is released, consumption is increasingly binged.

[Disclosure] Otter Media, which employs both authors, is the owner of Crunchyroll and Rooster Teeth. The contents of this article do not necessarily reflect the views of Otter Media or its portfolio companies.

[3] All subscribers drive affiliate revenues; aggregate viewers drive negotiations with MVPDs; individual viewers drive ad revenue in accordance with their own consumption).