1. Soon, TV networks will try to do 360 deals.

TV networks are really bad at capturing all the value they create with talent-centered shows. Take Comedy Central, led by the great tastes of Kent Alterman. The stars they’ve launched in the past few years alone – Keegan-Michael Key & Jordan Peele, Amy Schumer, Ilana Glazer & Abbi Jacobson – are tremendously popular. While these comics excel because of their immense talent, it was Comedy Central’s investment in their series and brands that enabled them to become stars and a part of the cultural zeitgeist. At the same time, the collapse of linear TV ratings has made it exceedingly difficult for the network to capture the vast majority of this value and influence.

And after these stars decide to end their hit series (as Key & Peele did earlier this fall), Comedy Central will receive none of the future value enabled by their investment, such as highly lucrative comedy tours, books, movies, HBO specials and so on.

It took years of declining album sales for the music industry to realize they needed another way of capturing the value created by financing and promoting talented artists. But today “360 deals” (which give record labels a piece of all revenues generated by an artist, not just recorded music sales) have become a key component of record deals. Maybe linear TV ratings struggles will lead networks to do the same.

Counterargument: The most obvious one is that talent’s representation would never go for it. But a lot of things that people thought networks wouldn’t want to retain, they eventually have (international rights, for example). And despite the popularity of the internet, the television is still the most surefire path to fame, money and mainstream awareness. This gives networks considerable leverage.

Another counterargument, which my friend Sriram pointed out, is that TV networks currently aren’t set up to do this. HBO wouldn’t be able to make a decent case that it should’ve published Lena Dunham’s recent bestseller, as it doesn’t have a vertically integrated in-house publishing division nor publishing expertise. It takes a company that can work fluidly across divisions to support 360 deals. And who is currently best positioned to pull off a multimedia deal? Amazon, for one – they do books, shows, movies, and even physical products.

2. The Pay TV ecosystem is actually much better positioned for the future than people give it credit for.

This is a fairly easy point to make at the moment, as right now media pundits (and the market) are giving it pretty much no credit.

All the talk and guesswork about the future of premium video is unnecessarily complicated. It all boils down to one thing: a race to who can get to a bundled subscription model the fastest.

Why bundled? Because nobody wants to manage fourteen different billing relationships. Bundles are by far the best way to sell and consume content. Another cliche you hear all the time on the media panel circuit is something to the extent of “Why should I pay for all of these channels that I don’t watch?” Well, Chris Dixon did a great job writing about the economic reasons for why this makes sense already. But to dumb it down even more, here’s what a viral video explaining it would sound like.

If People Talked About Other Bundles Like They Do Cable

- “Ugh, I only watch like 10% of the stuff on Netflix. Can’t I pay 89 cents instead of $8.99?”

- “I can’t believe I’m subsidizing your bacon at this breakfast buffet when I didn’t even try it.”

- “Can I just pay for the roads I drive on? I’ll tell you which ones they are before I go on them.”

And why subscription? Because ads alone can’t support digital video production outside of short-form green screen stuff, and a la carte transactional purchasing doesn’t allow new programming to be fluidly financed (you need the production budget before the production, of course).

. There are three things required for a bundled subscription model:

- People paying subscription fees to content brands producing video

- A way to manage all of those subscriptions cohesively

- A billing relationship with the consumer

Wait, that sounds exactly like… cable. All the cable ecosystem needs to do is make the transition to a slightly different version of what it already is (and do it over the next 2-3 years). Their approach thus far has been scattershot, but the recent “TV crisis” may force the players to confront digital competition realities and make TV Everywhere to go from a side project to a top priority. Easier said than done, especially when you’re forced to transition to a smaller and different version of what you are now, as viewing time goes down and prices keep rising. But even with all that working against it, I still think the current cable bundle is better positioned than pretty much everything else out there.

And of course controlling internet access to people’s homes helps too, in many ways – another point for cable. Michael Wolf’s recent presentation delved into the pricing advantage cable providers have over OTT start-ups (slide 81), amongst other reasons why “it’s cable’s game to lose.”

Counterargument: The obvious one is that the current ecosystem is too encumbered and massive to pivot into something new as newcomers come along free of legacy issues. Innovator’s dilemma etc etc. Another feasible counterargument is that Netflix will swallow everything (they have the above three requirements too) and their monthly price will keep creeping up so they can afford to do that. YouTube has a good chance to do this as well, since there are so many creators already feeding that ecosystem. YouTube Red is a step towards this direction.

3. We could soon see a few basic cable networks go ad free.

Sure that will decrease total revenue, but if they’re not making as many “filler” shows to fill a linear programming day, it might not affect the bottom line. To answer concerns about how many shows a network / content brand would need to get by, I’d quote Kerry Trainer, CEO of Vimeo — “You only need enough water in the pool so that nobody touches the bottom.” Also, having a content brand that’s well-defined and loved by viewers is going to be essential for networks going forward. An ad free experience would help with the latter, causing consumers to demand that channel in their bundle and perhaps pay a slight premium for the network. We’re already seeing seeds of this. Oh, and we may soon be at a point where nobody’s watching ads outside of live news and sports anyway.

Another point here – all content is used to sell something. Maybe it’s your own product; a Red Bull channel sells Red Bull simply by being on air, ads or no ads.

Counterargument: These networks need a healthy amount of content to stand on their own, and that level needs to be supported by a dual revenue stream.

4. “I don’t even know what network some of my favorite shows are on!” has no practical application.

You hear this as often on “future of media” panels as the bromide “where they want it, when they want it.” And it’s no doubt increasingly true. But that doesn’t therefore mean that TV shows are suddenly going to start existing unmoored and floating in the ether. The idea of premium shows disconnected from a content brand isn’t economically viable (or marketable). The primary reason being what/who is going to pay for them? A $100 million kickstarter for the first season of every big new show that nobody’s heard of? Let’s get real here.

Networks bring with them value that consumers are so used to they forget exists: lead-ins, lead-outs, etc. The post-Superbowl slot is going to see a ton of eyeballs, for example, even if the show itself is unappealing. This also applies to digital networks. When you finish a show on Netflix, you typically look for another show on Netflix. You don’t usually exit and switch to Amazon. As media fracturing increases, the “content brand” will matter even more as an indicator of tone and quality.

Counterargument: Maybe studios become the brand. Maybe the internet figures out fluid funding of new content.

5. To get to massive scale, a paid streaming video business has to get there through a non-digital backdoor.

Netflix did it via DVD rentals by mail. Hulu via a free library of current network TV shows. Amazon via expedited shipping on toothpaste. That’s useful background for the dozens of new digital video startups emerging today. Getting a general entertainment SVOD service off the ground from scratch, even with a healthy amount of funding, is really hard without some old school advantage — a library of content that broad (and marketing said content) is just too expensive. This makes one more optimistic on Seeso, having the benefit of the NBCU comedy library. A with-it VC told me he thinks 2016 will be the year of many SVOD rises and falls. Could very well be.

Counterargument: YouTube could get there and it doesn’t have analog roots, though they certainly had Google’s help. And we could see a social platform like Snapchat become a player in original content.

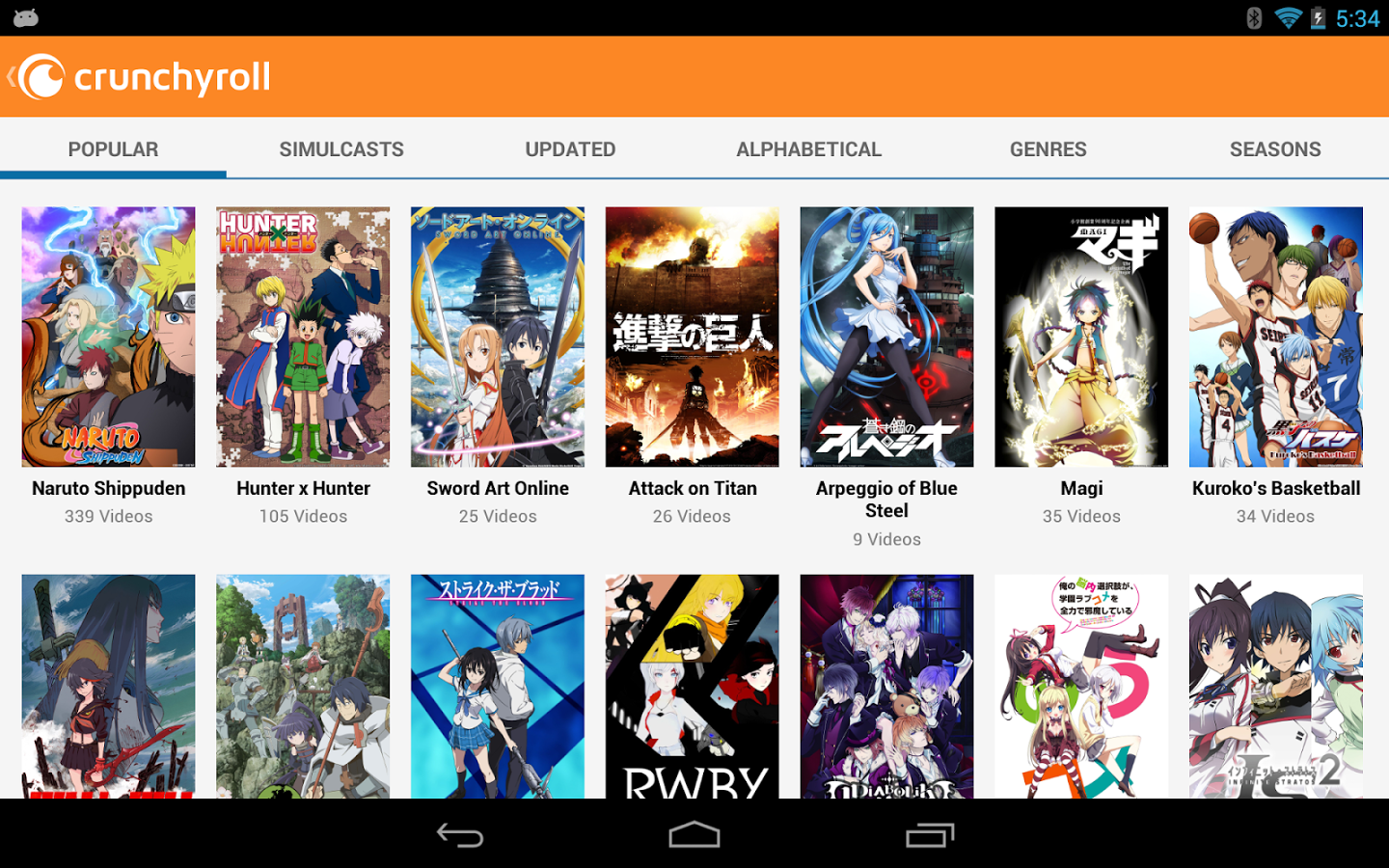

6. For a glimpse of the future of video, look at Crunchyroll.

If you don’t have an existing massive subscriber base for another product or the gift of a massive library, there’s another way to play the SVOD game: go niche. While it’s difficult to motivate people to pay for broad general content, small but passionate audiences will flock to where they need to go to get their genre (and usually pay up). Crunchyroll’s specialty is anime content from Japan. While there may not be a Sunday Night Football sized audience for it, there are way more people than you’d think. Today, Crunchyroll counts 700,000 subscribers, up threefold from two years ago.

And their approach was very smart: give away old episodes for free, but charge people who wanted to see new episodes day-and-date with when they aired in Asia. And despite the availability of the same content on illegal pirate video services, people paid! Crunchyroll has also grown a tight community with podcasts, events, and e-commerce. That’s the ideal model for a non-paid video service (to be discussed more in point #8), yet they’ve managed to build that on top of a paid service. Very impressive.

What’s next for Crunchyroll? If they’re smart (well, Chernin owns it, and he and his team are), they’ll carefully expand from there to other niche male-skewing interests. In the future, Crunchyroll could be as big in reach and scope as a mainstream brand like FX. But they never would’ve gotten there starting out with that large content breadth from the beginning.

Counterargument: There are also niche players with similar models: DramaFever with Korean dramas, for example, or lesser known sports leagues with rabid followings. And VHX, Patreon, and Vimeo are doing interesting things too!

7. Facebook is the internet (for now, at least).

Yes, it’s obviously a big generalization. But for most people the gateway to the internet, and the content on it, is Facebook. This doesn’t mean there won’t be popular marketplaces (Uber, Airbnb), heavily used messaging services (Messenger, WhatsApp – both of which are obviously also part of Facebook), or apps you use all day (Spotify, Slack). But those things are somewhat focused platforms, not the general internet. YouTube is a behemoth and it’s incredibly social, but at the end of the day it’s about watching video vs. Facebook’s much broader set of use cases. As for other social platforms- Snapchat, Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram – they have their places. But when people in tech and media company meetings say “social,” they really just mean “Facebook.”

What used to be “surfing the internet” is now just browsing Facebook. Kind of like how in the 2000’s, messaging/email/Napster etc were on the internet, but they weren’t what people thought of as “the internet.” That was the web. Facebook has taken the place of “the web.”

Counterargument: Maybe message apps take over everything, including consumption of content. Also, AOL was once “the internet” too…

8. “If you’ve got an audience, you’ll make money” is nonsense.

The gradual transition of video based media was best summed up to me like this: at first, there were three networks at the metaphorical track meet and everybody who ran got a gold, silver, or bronze medal no matter what their programming was. All pretty great prizes! When cable emerged, there was more competition for the top medals, but everybody still walked away with some reward for simply participating (after all, the stands were pointed at the track and there was nowhere else for the audience to look.) Then, with the internet, the track meet has turned into parkour.

The audience can now look wherever they want and, without the captive “track and bleachers” arrangement in place, the participants don’t get any guaranteed compensation just because they have somebody watching them. To compound this, media companies are forced to compete for attention so much that they’re often forced to give their product away for free.

And that’s where we are now. Sure, you can have lots of views on your content that you give away for free on somebody else’s super popular platform. That’s great, but that doesn’t guarantee anything. If you want to generate revenue from video, you have to do more than simply get it seen: sell merchandise, premium episodes, integrations, etc. Having an audience used to be a guarantee you’d make money. Now it’s just an opportunity.

Counterargument: Human attention is finite. Advertising dollars will eventually be allocated to where the attention is. (The counter-counter-argument: just because you’ve got attention doesn’t mean you’ve got a business. Just ask a pretty sunset.)

9. There are more news outlets than there is news.

I heard Barry Diller make this argument a few years ago. It was probably true before then, and of course it’s even more true now than it was when he originally said it. After all, what’s the upper limit on Donald Trump stump speech recaps before they start becoming redundant? How many digital publications do you need to embed this week’s SNL clips one at a time, add little to no value, and then share those posts on Facebook? Probably not many more than one. And, using SNL clips specifically as an example, there’s such a race to be the first to embed the same clip every other site will, publications are no longer waiting for NBC to post it online right after the show — they’re ripping it right off the TV and posting it before the episode even finishes airing on the east coast.

Much of the reason you see such homogeneity of stories covered in digital is that any newsroom worth its salt has analytics tools to measure what’s getting traction elsewhere online (whether that’s CrowdTangle, or just looking at Twitter/FB trends). So if a story is doing well with one publication, every other site essentially gets an alert that says “re-publish this as soon as you can.” Publishers that produce original content no longer have the time advantage they used to, where the creator’s site would get the traffic before others would catch on and “aggregate” the content. For example, when one of our illustrators at CollegeHumor releases a five panel cartoon she spent days on, it will be stolen and published somewhere else immediately if it’s performing well.

What makes matters even worse is that since headlines are A/B tested, the most clickable angle wins. Thus, the end result is like a game of media telephone, where the headlines get more salacious (and usually less accurate) with every iteration. Anyway, less of that please.

Counterargument: More opinions are good? I don’t have a counter-argument for this one.

10. We’re going to see a clear “hollowing out of the middle” in digital media over the next five years.

As a result of intense competition brought about by impression oversupply and the content glut I mentioned in the previous point, what we think of as modern digital publishers are steadily turning into simply creative agencies / production houses that conveniently use the “media” part of their business as a way to let potential clients know a) their voice and b) what type of content they’re capable of making. Vice didn’t get to their revenue size from banner ads and pre-rolls. They got there via big creative executions with clients who wanted to be associated with the brand they’ve come to know through the content it publishes.

But if you’re, say, Toyota, you’re only going to do a few of those “big creative executions” with a few select (and big) media brands. And you no longer need to advertise directly with fifty different publishers and ad tech companies to reach your desired audience, since you can now reach those people either via big platforms or very large programmatic players. Babs Rangaiah of Unilever recently made this point rather explicitly. “As a marketer, I just want the best solution available,” he said. “If the big companies want to buy up the small companies and use their technology, fine.”

This will force mid-tier digital publishers with real overhead and undifferentiated audiences out of the game. Other publications will survive because either their costs are so low that programmatic advertising can cover their expenses, they’re cross-subsidized by another business (see: Bloomberg), or they’re so niche in their coverage that their audience will be willing to pay (see: Jessica Lessin’s excellent The Information). Everybody else will get wiped out.

Counterargument: Diversifying revenue streams (paid content, commerce, subscriptions, affiliate deals) could keep the middle tier sustainable without relying on brand advertising. Publishers could find their inner Crunchyroll…

11. The “social referral” era will pass us by just like the search era.

We’re no doubt in the social era of the internet. But what many people don’t yet realize is that for media companies, the social era itself has two sub-parts within it: referral and distributed.

As you can see in the chart above by NowThisNews, the first three phases of digital media reflect on-site content consumption. Take Time as an example. During the first phase, people would type in www.time.com to read about an election. During the second phase, they’d Google “election” and end up at an article on Time.com. With the third phase, they’d end up on Time’s site because they clicked a link to an election piece shared on Facebook.

What’s happening now is consumption on the social platform itself: that Time link is now a video or instant article within Facebook. If you’re a publisher, that means your content is now consumed somewhere you don’t own, control, or necessarily monetize. It also means you need to rethink your entire company strategy and culture. You’re no longer in the business of selling ads, you’re in the business of selling influence and IP.

We’re already starting to see early effects of this shift in lowered traffic to websites, caused, I think, by increased on-platform video consumption, which is keeping people on Facebook rather than leaving to visit external links. This chart, showing where BuzzFeed views have been coming from lately, supports this thesis. It also could be the result of that aforementioned content glut. Consumption has remained constant while content production kept increasing (this has been termed “content shock“), giving less traffic to everyone across the board.

Counterargument: Not really a counter-argument, but if history holds, the distributed era will pass just like those before it.

12. Mark Zuckerberg is the most powerful person who has ever lived (this is a fun one).

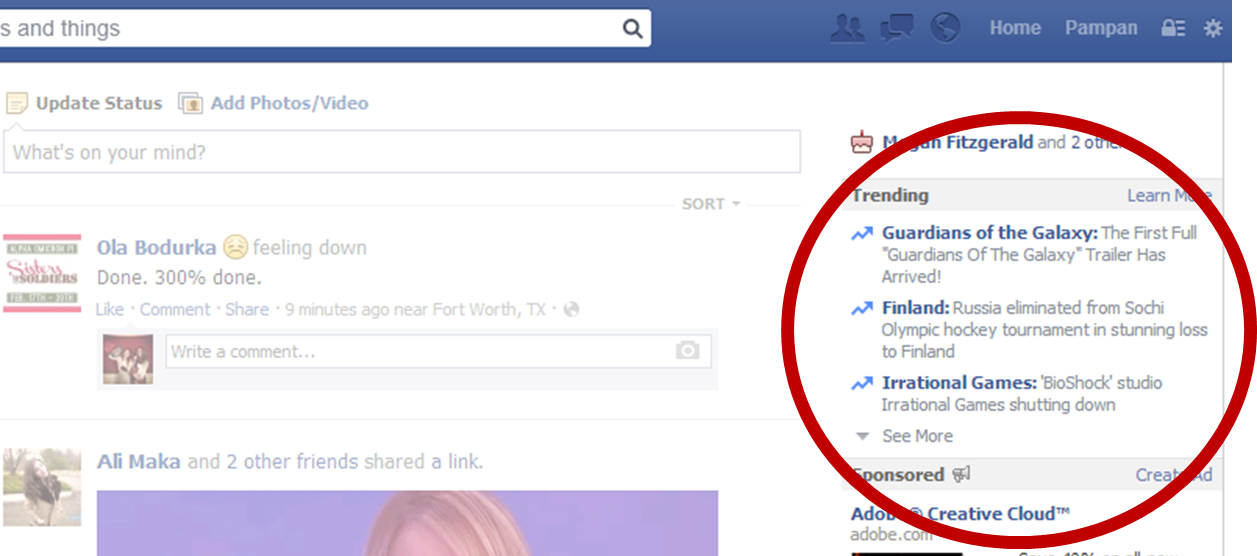

The “trending” section of Facebook is, most likely, where most of the developed world gets their news, whether they’d admit it or not. Each news item has a topic heading, followed by a brief summary. As most people only glance at the summaries, the wording is crucial – meaning, there’s a big difference between “Internet reacts to Hillary Clinton speech” and “Internet mocks Hillary Clinton speech.” Thus, the person who is writing that summary has immense influence in shaping the national conversation. Mark Zuckerberg is that person’s boss’s boss’s boss’s boss (approximately).

Facebook has gotten so big it’s easy to forget that it’s still completely controlled by a single 31 year old human (worth $45B+). But it is! And if you believe proclamation #7, that Facebook is the Internet, then by the transitive property, this one person is arguably the gateway to the primary source for news, commerce, and communication for pretty much the entire world.

With one code push, Facebook could materially impact (perhaps fatally) the viability of most news publications. It could block Fortune 500 companies from reaching their customers as efficiently as their competitors. It could send an alert to every spouse in the world at once if their partner has actively been in touch with an ex. Just scratching the surface here, and again, that ability is with one person.

You may be thinking “Well, what about heads of state? What about media moguls like Rupert Murdoch?” To answer the first question, I would argue that Facebook is more powerful than a single nation as its reach is worldwide, excluding the obvious few censorship-prone countries. And as for the latter point – if Rupert Murdoch wanted to influence the outcome of an election, we would know he was doing it. If Facebook wanted to (which it easily could of course, via a simple tweak in an algorithm), we’d never know. Users only see around six percent of the content their friends post as is, so who would think to wonder what’s in the 94% being filtered out?

Counter-argument: Facebook may be powerful, but it’s still subject to laws and regulations. And unlike North Korea, it’s not going to acquire nuclear weapons and threaten the entire world. Also, it’s hard to argue that Mark isn’t a wonderful human being who has consistently demonstrated a desire for the world to be a better place. So, there’s not much of an “issue” here to begin with.

13. The internet kind of sucks right now.

There may be many other reasons people give to support this, but here are a few:

It’s the same shit over and over.

The medium has matured and what used to seem unique is now not only expected but pretty much guaranteed – a celebrity in an internet video, a Twitter account set up for an inanimate object from a pop culture moment, the same outrage and jokes about Columbus Day as last year, pretty much verbatim. Every day it’s same syntax with slightly different proper nouns that rotate through. Who are we taking out of context and putting through the outrage cycle this week? What topic did John Oliver TOTALLY NAIL in his monologue last night? And how many TBT’s worth of baby photos could your parents have possibly taken??

Everybody’s constant identity creation is getting exhausting.

My friend Andy observed that the best social services are those that make you feel like you are someone or something else. Instagram makes you feel like you are a professional photographer, Medium like you’re an Op Ed columnist and so on. But living in a world where everybody’s constantly pretending to be the best version of something they’re not (aka fronting) can get tiring, and as studies have shown, depressing. As can, on the opposite side, always living a life curated for others.

The Negativity

Obviously there’s irony in making this a sub-heading under the statement “the internet kind of sucks right now.” But this mainly refers to the person-to-person venom and trolling that’s become rampant. Which when you think about it, seems inevitable in the social media age: in 1990, a radical feminist in Brooklyn Heights probably never would’ve run into a diehard rural conservative. Now they’re put in the same room every day, only without the benefit of eye-to-eye contact that can humanize even the most polar of pairings. The old saying “if you can’t say something nice, say it on the internet” is seemingly more true than it ever has been.

Counterargument: The internet is awesome. It’s allowed us to do amazing things we never could have done, connect with great people we never would have met, and made everything cheaper and accessible for the average consumer. Also, THE DRESS!

14. Snapchat is for young people and always will be. And that will be just fine for them.

When I was in middle school, there was a semi-dirty video game called Leisure Suit Larry that my group of friends was into. To verify you were old enough to play, the game would ask you a series of questions (this was pre-Google). Snapchat, via its interface, seems to serve the opposite purpose. If you can’t figure out how to use it, you’re too old. While I doubt that’s done on purpose, it has certainly helped Snapchat, unlike Twitter and Facebook, stay the exclusive domain of the young.

And I don’t think that’s a bad thing. This article by Tom Dotan dug into this idea a bit. There are, obviously, a lot of young people in the world. And owning that demographic is probably better than diluting the core product to widen the audience. It also makes it easier for Snapchat’s advertising and original programming ambitions to come to fruition. Snapchat, by its founding principle, doesn’t keep track of its users’ demographic information. That seemingly would make targeting problematic when trying to reach a particular demo. That is, unless there’s only one demo that cycles through Snapchat much like generations cycle through Disney or Degrassi.

Counterargument: This one has a counterargument that’s extremely solid– Facebook was once seen as a utility for college students to hook up with each other, and eventually grew up with its audience. Maybe Snapchat will too. And the next generation will see Snapchat as “for the olds.”

And that concludes this edition of “things we’ll look back on and realize we had no clue, but why let that stop the fun now?”

Ricky Van Veen is the co-founder of several internet properties including leading comedy brand CollegeHumor and video sharing site Vimeo. He is currently at IAC, overseeing the TV, film and digital endeavors of CollegeHumor as well as other productions such as “Chopped” on the Food Network. He lives in New York City and can be found at @RickyVanVeen.