Sports programming is to the rest of TV what the Golden State Warriors are to the rest of the NBA: seemingly unbeatable. In 2016, 92 of the 100 most watched broadcasts in the US were sports or sports-related. But as with the Warriors, who ended their 2015-16 season with a 73-9 record but were stunned by the Cleveland Cavaliers in the NBA Finals, what seems a sure thing today may not be such a sure thing tomorrow.

The sports-media ecosystem is more unstable than it has ever been. As television engagement continues to decline, as new distribution technologies continue to emerge, our great love affair with sports is on the verge of a major shakeup. Sports content, long the life raft for the traditional media ecosystem, is approaching a turning point in which it will need to adapt in order to thrive, and in doing so it may upend much of the remaining stability in the TV ecosystem. While sports and television have been so intertwined as to effectively be synonyms, it is unlikely that the two will remain neck and neck in the near future.

Carrying the Team

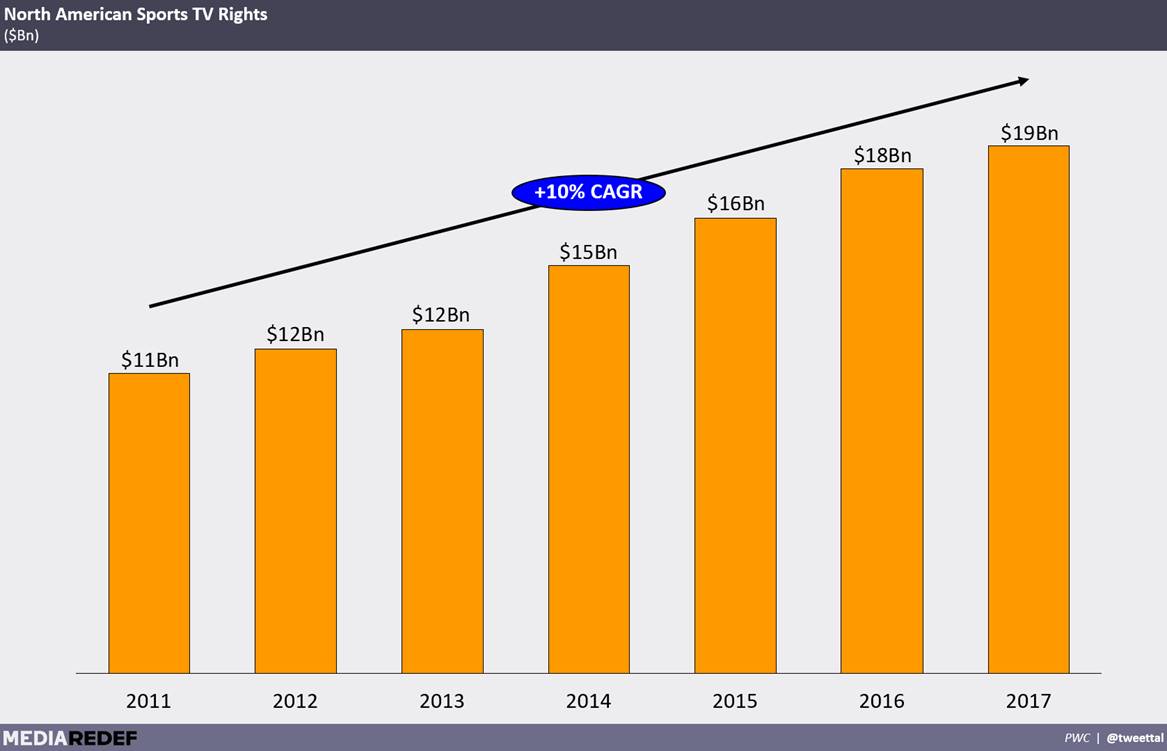

No other content has been more popular, monetizable and lucrative. Americans watched more than 31 billion hours of sports content in 2015, according to the Los Angeles Times. In 2016, 10,869 sports events were broadcast nationally, up 8% YoY. Twenty-seven of the top 50 broadcasts belonged to the NFL. Of the top 10 networks by affiliate fees, six had major sports rights (the NFL alone delivered more than 60% of Fox’s live and same day ratings points). Sports accounted for nearly 40% of total TV ad spending, according to Adage, and PwC estimates that networks’ 2016 revenue from sports was over $30bn.

The NFL’s TV contracts were worth more than $5bn per year, the NBA’s nearly $3bn and the Olympics nearly $1bn for the US rights alone. In total, leagues and teams received nearly $20bn in licensing fees. Sports programming is the most valuable audience cultivation tool for networks hoping to launch other content and a critical customer acquisition play for pay-TV distributors.

Down in the Count but Not Out

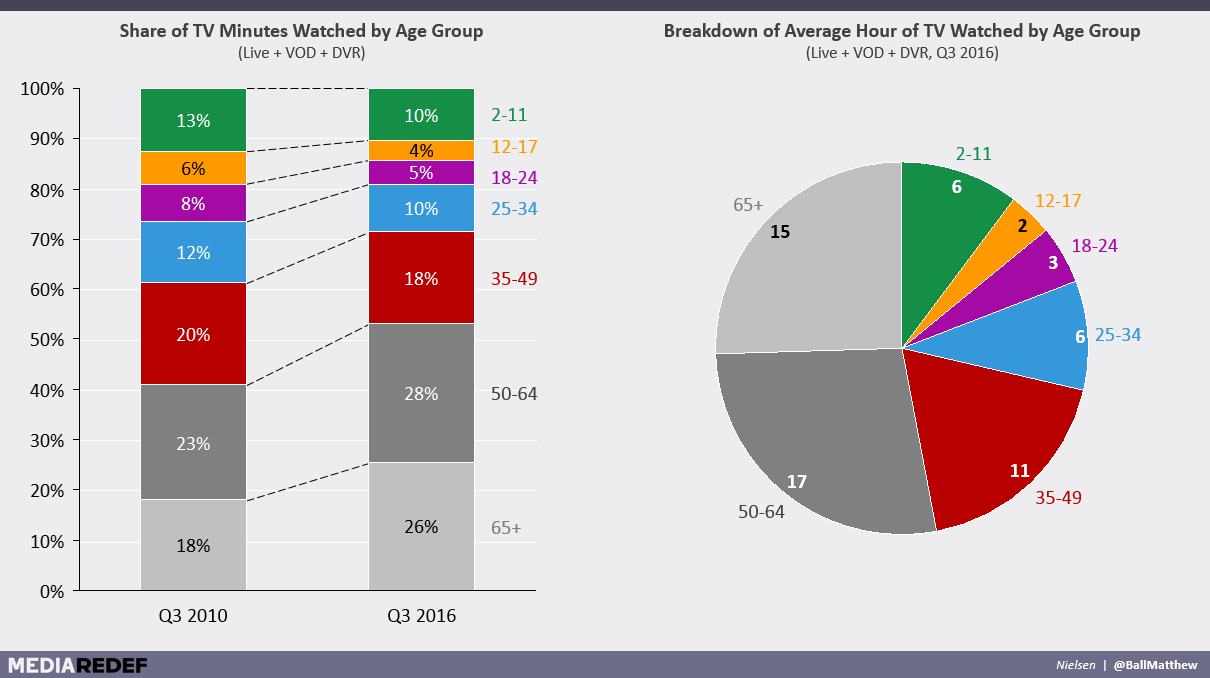

But this state of affairs is approaching its expiration date. As sports rights continue to grow in both value and length—the current NCAA basketball deal with CBS and Turner is 14 years long—the TV bundle is showing serious signs of fraying. Overall television viewing in 2016 was down among key audiences, with time spent watching down more than 40% from 2010 for 18-24s and more than 30% for 25-34s. Cable penetration has not dropped as precipitously but it, too, continues to decline In 2017, for the first time since the turn of the century, more than 25mm consumers are outside of the pay TV ecosystem.

While sports content has long been the lone ray of sunshine against this bleak backdrop, that sunlight is diminishing. ESPN is down to 88mm subscribers from its 100mm peak and its losses are accelerating. NFL viewing dropped 9% in 2016, with the league experiencing an alarming 12% dip across all windows before the presidential election and a softer but still worrisome 5% drop post-election, according to Recode. National windows performed particularly poorly, with ESPN’s Monday Night Football down 13% and NBC’s Sunday Night Football down 11%. This isn’t just an American, or football, blip. English Premier League viewing was down around 11% in the UK and similarly in the US.

Americans certainly love sports and we will not wake up tomorrow in a world that eschews football, basketball and the rest of the big American pastimes. The 2016 NFL season was still the third most-watched ever, the World Series enjoyed its biggest ratings in 25 years and game seven of the NBA Finals set a league viewership record. Unique among TV programming, sports has a built-in, deeply vested audience. And unlike other entertainment content, it’s nearly impossible to create a competitive product. You can’t create a new pro sports league as easily as you find a new script or come up with a reality concept.

Americans certainly love sports and we will not wake up tomorrow in a world that eschews football, basketball and the rest of the big American pastimes. The 2016 NFL season was still the third most-watched ever, the World Series enjoyed its biggest ratings in 25 years and game seven of the NBA Finals set a league viewership record. Unique among TV programming, sports has a built-in, deeply vested audience. And unlike other entertainment content, it’s nearly impossible to create a competitive product. You can’t create a new pro sports league as easily as you find a new script or come up with a reality concept.

But the media ecosystem is not as healthy as it once was and sports is no longer an invulnerable exception. It can’t weather shocks as it once did. Presidential elections historically have reduced football viewing by 2%, but in fall 2016 there was a double-digit dip. At REDEF, we’ve written about the dead cat bounce of the entire media ecosystem, and sports will not go unscathed. It has taken longer, but sports content will need to adapt to the realities of the digital age.

Calling an Audible

Sports content accounts for nearly 40% of the cost of a typical pay-TV package, according to SNL Kagan. Traditionalists argue that pay TV will remain strong as long as consumers value sports. But if viewership, and therefore the value, of non-sports content continues to fall, the underlying economic decision will tip against the pay-TV bundle, regardless of trends in sports viewing. At some point, unless consumers value sports at nearly the entire price of the package, they’ll cut the cord to avoid paying for all the content they don’t watch. In other words, even if sports ratings don’t continue to slip, sports rights deals are going to become increasingly expensive relative to their value to networks—and increasingly a source of stress.

Adding to that stress is that sports-licensing deals, for all their ratings and revenue potential, are often loss leaders, used by networks and distributors to attract consumers to other offerings. That model makes sense as long as it successfully drives viewership on other properties. If networks continue to bleed non-sports viewership and cable penetration continues to decline, the strategy is unsustainable even if the underlying sports properties remain healthy. To make matters worse, even directly profitable deals often lose money in the early years, with the value expected to be generated from increased advertising sales and affiliate fees in later years—all predicated on ever-increasing viewership and engagement not flat or declining consumption.

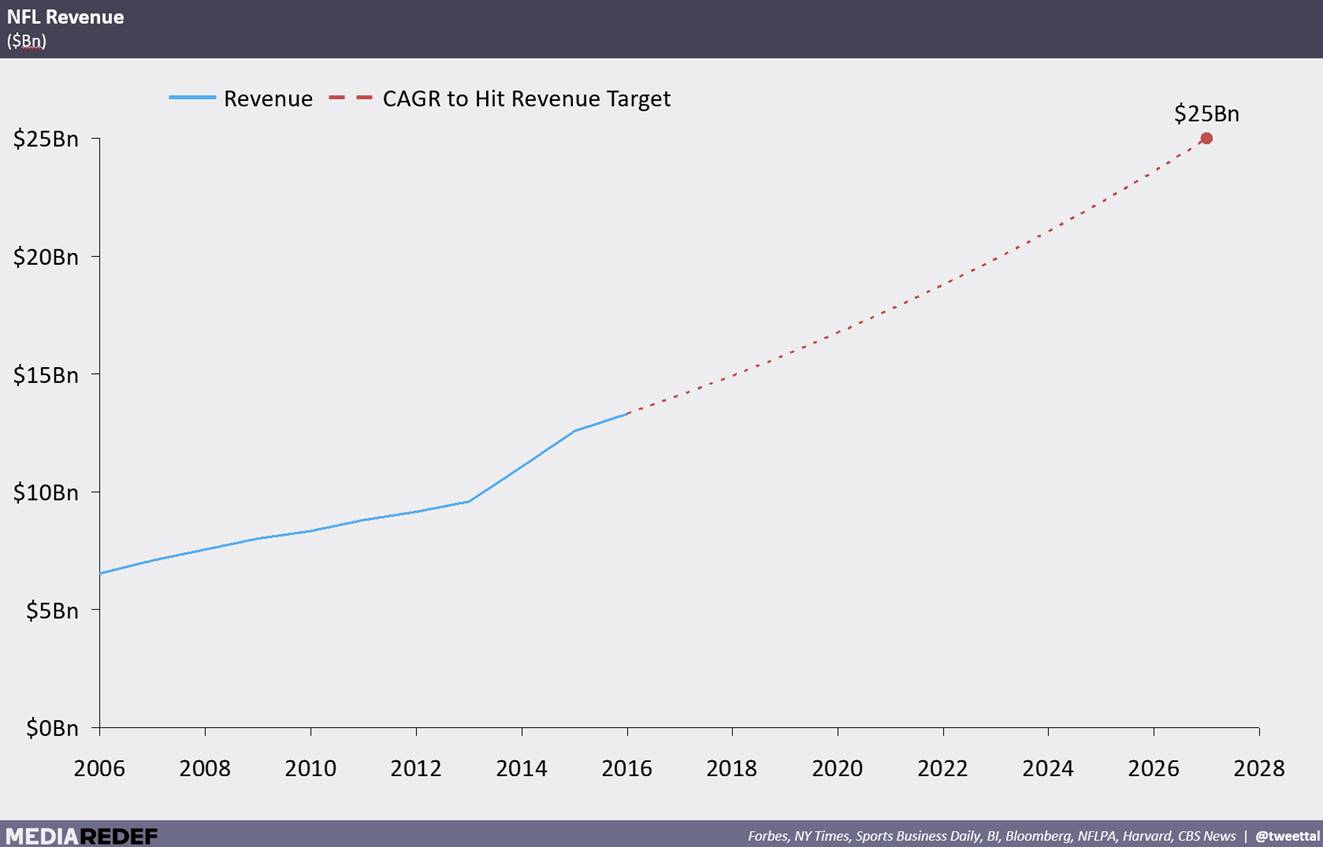

In that case, networks and distributors might seek ways to offset the downward shift. Of course, these deals are contractually locked in, and leagues would need to agree to any changes. But leagues may have good reason to do so. In 2016, people age 50 and over represented nearly 55% of total TV viewing—up from 41% in 2010. Sports TV viewership is aging, too: While overall NFL viewership declined 9% in 2016, it was down nearly double that for ages 12-24. That’s a problem for leagues. As audiences continue to fragment and younger viewers accustomed to on-demand and OTT services clamor for content where they want it, when they want it, pressure will mount on leagues to deliver it to them. They’ll need to keep reaching young viewers and refreshing their audience to hit their aggressive long-range revenue targets. The NFL, for example, is aiming for $25bn revenue by 2027.

Leagues will be hard pressed to reach such targets without committing to new offerings, mostly digital, and new monetization schemes based not on windowing but on price discrimination. These offerings of course, are hamstrung by the existing licensing agreements. They also require technology and direct-to-consumer experience that traditional distributors lack.

It’s a long shot, but conceivable, that leagues and distributors could re-trade these sports rights or renegotiate the terms by the end of this decade or the beginning of the next.The leagues may be making too much money in the short run to focus on the long-term consequences of continuing down the current path. The networks may be averse to effectively declaring surrender—and most of the major current deals run into the 2020s, which gives them time to build capabilities for the digital future before the next round of rights bidding begins.

Either way, by the time the deals are up, it will likely be less a question of whether digital distributors are bidding but rather of which digital players are winning and whether the leagues will decide to go direct-to-consumer themselves. (It’s also worth noting that government regulators may still have an interest in ensuring free access to national pastimes; it’s hard to imagine Congress being excited about sports content disappearing from the free broadcast airwaves.)

Swinging for the Future

While the timing and deal-making may be uncertain, the future of the product experience is less so. Just as the rest of the media business is shifting from a model based on windowing (placing content across various channels and slots to maximize value), to one based on price discrimination (users choose among varied options, some deeper, some shallower), so too will sports. The future isn’t one offering; it’s many. There will be a sports package of national interest that cuts across the major sporting events, and regional bundles focused on teams with significant audience overlap, akin to today’s RSNs (but sold both a la carte and as part of new digital bundles). Given the cross-sport nature of these offerings, they will likely be delivered by an aggregator instead of leagues and will likely be bundled with other digital offerings (and not just other video content; think Amazon Prime). Hardcore fans will be able to subscribe to deep single-league experiences likely sold direct to consumer. They’ll also be able to buy deep single-team experiences. These will be packaged via various digital distribution channels and sold at various price points.

But the real innovation will come in how offerings vary in the intensity and exclusivity of experiences. Similar to mobile games industry’s whale system of monetization, in which a tiny fraction of high-spending users generate most of the revenue, these offerings will allow for deeper monetization of more engaged fans. High-priced experiences will include more than just traditional content. There might be merchandise, live events, advanced analytics, even direct connections to players, coaches and executives. The sports training market is already worth $7bn annually, and DTC offerings like Lucid, which delivers mindfulness and psychological training for athletes, are seeing success with monthly subscriptions. It’s easy to imagine the NFL, as part of a high-end subscription, allowing young quarterbacks to train on real game tape and receive instruction and coaching from pros. VR will only make such an offer more compelling. For lightly engaged fans, free, highlight-based social experiences will allow basic engagement on their own terms. These won’t be viewed as freeloaders but as a critical part of a healthy funnel that leads into high ARPU offerings.

In an OTT era, all media is targeted media, even the most popular media. When analysts calculate how much ESPN would have to charge in a direct-to-consumer OTT world to maintain their current business, they miss the mark. There won’t be a single package at a single price point. There will be many. That doesn’t mean any one distributor will be as profitable as ESPN in its heyday. But looking at OTT as simply television on a different device is simplistic. Successful distributors and leagues will stop thinking of each consumer as being worth the same money and stop thinking that growth comes only from reaching more people or raising everyone’s price. They will stop thinking of sports simply as mass media.

In the Redzone

The viewing experience is likely to become more differentiated, personalized and individualized. The days of one feed with two announcers in the booth are numbered. A platform such as Facebook could acquire the rights to stream Thursday night NFL games but create multiple experiences to create the most engagement. The platform could partner with brands and influencers to create multiple broadcast feeds, each with its own focus, and target them based on viewers’ preferences and previous engagement. There could be a data-heavy broadcast for one audience, a Barstool Sports stream for the comedy-inclined, a Bill Simmons broadcast for a pop-culture audience, a Sports Action stream for gamblers, etc. Each experience could be monetized at an optimum rate and bundled with other experiences, merchandise and content to increase engagement. ESPN has already run limited experiments with such a setup. (Twitter seems to be heading down a similar path with its video products, and on the day this article was published, word leaked of discussions between MLB and Facebook for streaming games on the social platform.)

The sports viewing experience of the future is also likely to build on the innovations of the NFL’s Redzone channel, which shows the most important action happening at any given time. NBA commissioner Silver has hinted at a similar offering for his league. As Sports Illustrated’s Jacob Feldman suggests, such offerings will be highly customized. Instead of one Redzone channel, imagine many, each tied to individual viewers’ preferences, fantasy teams, rooting interests and more. Instead of the standard replay or two after a big play, viewers will receive a tailored stream of replays, analysis and commentary, with targeted notifications to let them know exactly when to tune in. Everything will be optimized for each viewer. A million viewers will have a million unique experiences with the same game. Want a feed of your favorite three players? Want to see Kristaps Porziņģis’ every movement along with his advanced metrics? Just as Netflix isn’t one monolithic service but many things to many people, sports offerings will stop being one-to-many broadcasts and instead become one-to-few or one-to-one.

But all this personalization and fragmentation and extension doesn’t have to come at the expense of the collective viewing experience that has helped make sports an American religion. It can, in fact enhance it. Thanks to the targeting ability of social and digital platforms, curling of badminton fans around the world will be able to connect with each other from their couches. They’ll be able to watch exactly what they want with other members of their tribe. Every niche will reach its true scale. Every tree will find its forest.

Picking Up the Flag

Eventually, sports will have to admit its not-so-secret secret—its symbiotic relationship with gambling—and capture direct value from it. Sports content has long been intertwined with our vices—turn on a game and notice the beer ads. Sports and gambling are uniquely intertwined. There are nearly 40 million US gamblers wagering an average of $158 per bet, according to research by the Chernin Group [full disclosure: the author works for Chernin, a digital investment and operating company]. They are heavily invested in the sports they bet on and, therefore, voracious content consumers. Nielsen estimates gamblers watch 19 more NFL games per season than the average viewer. The relationship works both ways, with the New York Racing Association reporting that its handle was up 10% YoY in 2016 due in large part to FS2 broadcasting races at Saratoga. While pro leagues and teams have embraced daily fantasy, they have been wary of cozying up to pure gambling because of concerns about morality, the acceptance of gambling by bread-and-butter audiences and sponsors and a fear of tainted competition. But Americans are increasingly open to gambling, as recent successes in legalizing sports betting in states such as New Jersey and the momentum of the national legalization push demonstrate. Other forms of media are successfully attaching themselves to indirect revenue streams that don’t rely on directly monetizing content as media as a whole rapidly becomes a loss leader (see Amazon video’s connection to its Prime delivery model and AT&T’s purchase of Time Warner). Gambling represents the shortest path for sports to do the same.

Winning the Game

To succeed in this future is not a divine right. There is no universal law that says sports must be the most popular content. Nor one that says it must be distributed via ESPN. Outsized value will be earned via forward thinking and bold leadership. The leagues should build their own distribution capabilities while collaborating with both traditional and digital distributors to build the foundations for the future. They should embrace sports bettors as invested fans, not as threats to their games’ integrity. Traditional distributors should use the length of their current rights deals to build the infrastructure they’ll need to support direct-to-consumer experiences, including sophisticated subscriber acquisition marketing and product and engineering organizations that can compete with the best of Silicon Valley. Disney’s 2016 acquisition of part of MLB Advanced Media was a step in the right direction. Lastly, digital distributors should accelerate their efforts to acquire any and all sports rights they can, even if the price seems hefty (currently on the market: Indian Premier League cricket). All these players will need to experiment and adapt; those that do sooner rather than later will come out ahead.

But just as with sports themselves, media champions are made not born. Winning comes from years of determination and preparation, and the game is far from won.

Tal Shachar is an entrepreneur in residence at the Chernin Group, a media-focused operating and investment company based in Los Angeles. The company has investments in two companies mentioned in this article: Barstool Sports and Sports Action. The views in this piece do not necessarily reflect those of his employer or its holdings. He can be found @tweettal or tal.shachar@gmail.com.