Blessed is he who, in the name of profit, shepherds the user through the funnel, for he is truly his user’s keeper.

–Startup L Jackson

Ever since we progressed from subsistence farming and bartering to localized trading, almost all commerce has required marketing. To sell a product, a customer had to be made aware it existed, taught what it did and how it differed, inspired to feel the need to buy it, and actually enabled to make the purchase. Today, this process is known as the customer acquisition “funnel” – and it underpins virtually all marketing and sales activities.

Unfortunately, this unavoidable process was mostly characterized by its flaws. First and foremost, sellers had a limited ability to identify or target those who might need or buy their product. They could always use more segmented channels (e.g. advertising on Oxygen instead of NBC), but targeting remained inelegant and inefficient. Not only were more target consumers missed than hit, the majority of those exposed to an ad weren’t those the ad was actually targeting. And regardless of their ultimate “hit rate”, brands knew very little about those exposed (let alone receptive) to their advertisements. These struggles extended beyond general awareness advertising (i.e. the very top of the funnel). Marketers had almost no information on who was going through the funnel and experienced significant drop off at each step – without knowing why, where, how or precisely who.

What’s more, the costs of funnel failures were overwhelming. When a customer did get through the entire funnel (and was ready to make a purchase), the brand needed to make sure the product was in stock and available nearby – which meant a host of (margin eating) retail partnerships and predictive investment inventory (themselves based on scarce data). Under-prepare or distribute and a sale is lost. Over-prepare or distribute and you incur significant cash losses. Collectively, these limitations created a three-tranche dynamic to the funnel:

- For the vast majority of consumer products, the very top of the funnel became the focal marketing activity. The best way to survive constant drop-off rates was to start with the largest base of potential customers. Furthermore, the top of the funnel’s primary metric – brand/product awareness – was the easiest for agencies and marketers to assess

- The (thick) middle of the funnel, meanwhile, was largely de-emphasized. Even though its importance was clear, brands could do little to measure, modulate or optimize mid-funnel performance. As a result, market competition concentrated elsewhere

- Finally, the bottom of the funnel became a defensive (and expensive) war of attrition. Brands focused on buying distribution and utilizing blunt instruments such as mass mailing to try and push potential customers over the edge into purchase. These efforts drove clear, measurable sales and were thus critical to revenue growth. However, they remained wasteful (e.g. sending all customers discounts, including those who were going to purchase already, in order to convince skeptical ones to buy) and reliant upon top-of-funnel breadth to get customers there in the first place

Life in the Dark

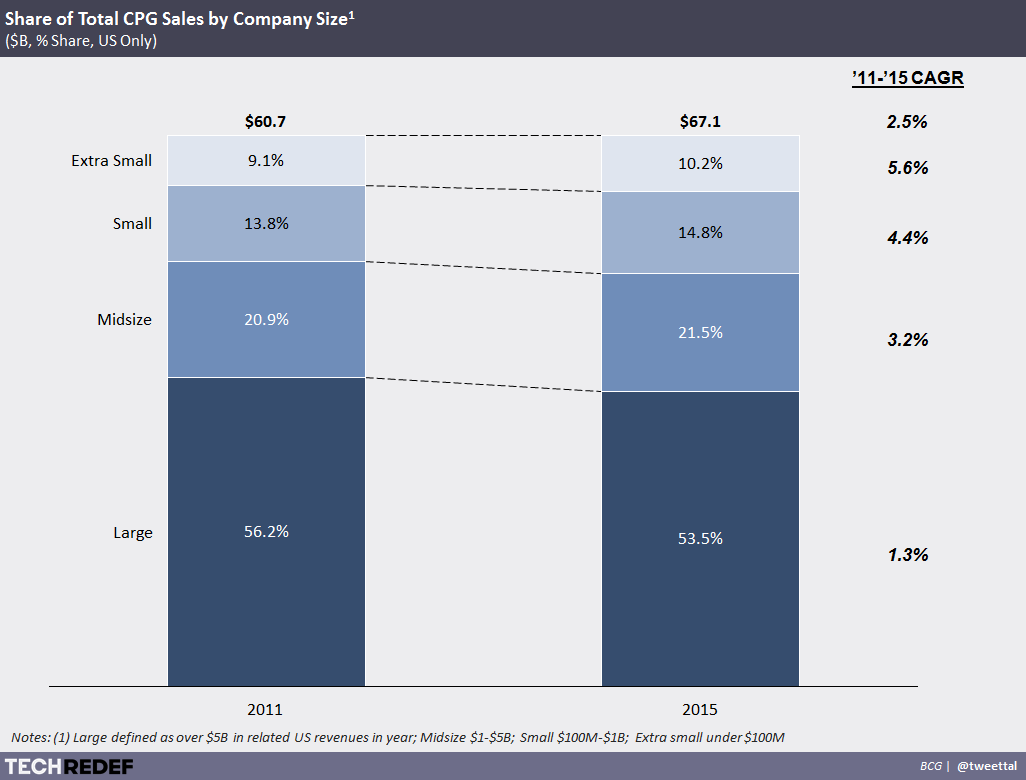

What did this mean for consumer products? A world where money and mass customer bases ruled and competition was insular. Major brands crowded out key marketing channels (via pricing pressure or buying out of limited newspaper/TV ad inventory) and locked down retail distribution (e.g. end-of-isle displays or shelf-space), making it hard for smaller companies to compete outside of local communities. Furthermore, only the largest market players could endure costly funnel inefficiencies. As a result, the “natural” carrying capacity of most consumer markets was limited to only a few participants. Meanwhile, the friction involved in going through the funnel made competitive comparison tough and left consumers artificially loyal; most simply defaulted to what they knew.

The mix of poor data, imprecise targeting, limited shelf-space and sticky customers was great for big brands but terrible for everyone else (there’s a reason so many categories – FMCG, apparel etc. – are known for being terrible businesses to enter). It also meant TV was the focal medium for advertising. Not only did it offer the greatest reach, it offered the best top-of-funnel metric (how many people saw the ad), as well as the easiest to test (“what’s product awareness?”). However, television advertising lead times were long – making messaging pivots tough – and efficacy research heavily lagged. This resulted in a model of “wait and pray”, characterized by the common refrain that “we know 50% of ad spend works, we just don’t know which 50%.” Most marketers would simply advertise where they thought their customers were and then hope for the best.

Collapsing the Funnel

Despite their longstanding nature, these constraints have been progressively peeled back by the digital ecosystem. Thanks to mobile, it is possible to purchase virtually any good from anywhere at anytime. There are in effect no location, SKU, or stock limitations; no need to convince someone to come into a physical space in order to interact with or buy products. And as audiences have fractured and fragmented across media, advertisers can no longer monopolize channels as they once did with primetime TV advertising. Not only is there too much inventory available, digital ad delivery makes it possible for advertisers to reach two different demographics watching the same content at the same time (today, a grandmother watching Pretty Little Liars generates virtually no incremental ad revenue).

At the same time, the middle of the funnel has finally become addressable. Customers can be tracked and evaluated based on engagement (how many times they viewed a page, what’s in their shopping cart and for how long), then followed across the web to reiterate the message and sent bespoke offers to close the deal. Digital advertising also provides real-time feedback, enabling brands to adjust and hone their messaging on the fly and directly engage with (and cultivate) consumers. SEO and semantic analysis (e.g. Google analyzing Gmail content), meanwhile, allow brands to capture purchase intent at the very bottom of the funnel. And finally, we’ve seen massive change in what it takes to actually get a product into a would-be buyer’s hands thanks to one-day delivery, free returns and “ambient inventory” that’s pre-fulfilled based on anticipated zipcode orders.

Each of these changes is individually important, but collectively they’re profound. Not only do marketers now have the ability to understand and test against every step in the funnel, consumers have the ability to go through the entire process in a matter of minutes, no matter where they are. As a result, the traditional marketing funnel will be fundamentally transformed. The steps will remain the same, but rather than starting wide and aggressively narrowing, the digital-era funnel will be both shorter and thicker. Accordingly, we’ll also start seeing a blending together of brand-and-direct advertising. They’ll be too close together and intimately connected to stay separate.

Heard It. Haven’t Yet Done It

Skeptics might argue that the ‘digerati’ have been foretelling the end of the traditional marketing process for more than a decade. So why now? While many of these changes have long been gestating, most are only just coming to term. Ecommerce continues to eat retail and has finally reached meaningful scale. On-demand infrastructure, including Post-mates, Amazon Prime Now, and drones are on the cusp of making instantaneous delivery a reality. On top of that, mobile has enabled online-to-offline handoffs/tracking (e.g. Facebook Atlas) and created a vibrant ecosystem of payment and commerce enabled services. In addition, the social platforms – which have considerably grown their share of video time and ad spend – are also transforming into commerce destinations via buy buttons and shoppable ads/pins. Digital advertising – be it on an O&O website, Twitter account, Facebook page, Instagram or Tumblr account – has led many brands to develop not just direct-to-consumer relationships, but to focus on super-serving sub-segments. Brands that want to focus on highly specific, niche audiences can now do so profitably and reliably. And although TV remains the focal point of advertising, audience engagement continues to decline – especially among young, high-in-demand viewers.

To believe that these changes won’t disrupt a century old process is to take for granted why the traditional marketing funnel operated the way it did: because there was no alternative. For the first time in centuries, the marketing process – start to finish, from advertising through to fulfillment and sale – has been completely opened up. Given these changes, the powerful age old CPG brands, large agencies of record, traditional media platforms and other champions of yesteryear, will need to re-architect themselves or face the real risk of losing out to newer, more nimble competitors. For proof, look no further than Victoria’s Secret making the decision to shut down its iconic catalogue (saving $150mm per year) in favor of emphasizing digital platforms and new channels (Instagram in particular).

What Will Happen for Brands:

The major brands will encounter unprecedented competitive pressures. With the reduction of friction involved in going through the funnel, customer loyalty to brands without truly differentiated offerings is likely to decline. Decreased information asymmetry and increased ease of comparison will further erode stickiness – especially for products that aren’t for a highly specific demographic. This will commoditize many of the goods that – though fundamentally undifferentiated today – command substantial price premiums in market. As brands converge to using FB/Google/Amazon to advertise and sell products, the brand will be the product and everything else will be a commodity. Amazon’s entry into its own food, detergent and diapers is just the beginning; you can’t compete with Bezos on price in a commodity category.

In this environment, brands will need to do more than put forward a functional product or brand position. Marketing will no longer be an activity needed simply to sell a product but actively part of the product experience itself – one that will create an intangible attachment that earns a premium. Consider Bevel, a grooming brand for men of color. Central to their business is Bevel Code, a content marketing arm that has become a destination in its own right and works to earn – not push – Bevel’s claims of authenticity. To this end, one can hardly separate the physical products it sells from the intangible holistic experience it creates for its audience and community. Shopjeen, an iconoclastic ecommerce brand, similarly goes beyond selling products or even a lifestyle to selling access to a specific community built and patroned by young women. Triangl, a swimear company out of Australia, built a $100m+ business entirely via using Instragram and social influencers to sell an idea and not just a product. These types of approaches have not just turned the brands’ founders into social influencers (unlike the Oprahs and Martha Stewarts of the world, who moved from celebrity personalities into products), they have enabled and accelerated the emergence of brands competing in previously stagnant markets – even though these companies boast a fraction of the distribution, balance sheet and history of the incumbents they’ve attacked. While it took Nike 14 years, Lululemon 9 years and Under Amour 8 years to reach $100mm in annual sales, we’ve already seen nearly 10 new brands each reach such a height in less than four years, with the majority founded after 2010.

Naturally, the transition away from marketing as a sales tool and towards marketing as a product feature will only increase the growth of branded content initiatives. At the same time, it will make it more important than ever that a company’s brand and its advertising strategy are controlled internally. Rather than just creating (or commissioning) a campaign, putting it out in market and waiting for results, brands will be constantly investing in and developing their consumer relationships, particularly for those focused on building on-going subscription based relationships (an increasingly popular tactic, in part a reaction to the collapsing funnel). Agencies can do this, but marketers must think deeply about how much they want to be disintermediated. If soft-marketing is so critical to their product, they can’t outsource all content production, analytics, optimization and engagement management.

The connection of advertising and commerce will also blur the lines between brand advertising and direct advertising. If an ad drives to an immediate transaction, what’s the difference? What’s more, digital brand advertising will be tracked, A/B tested and optimized based on its ability to generate sales, similarly to direct advertising. This changes not just how you spend, but where and how much. Now, brands can be very tactical about what they spend to secure a customer or sale. In time, the core concept of a maximum ad budget will even start to erode, as brands will (or should) continue to spend as long as a unit’s gross profit or the customer’s lifetime value remains positive. If the ROI is there, you keep pushing.

This tight feedback loop, meanwhile, reinforces the need to pull ad capabilities in house. While new channels and capabilities will shed light on previously unknown and unaddressable marketing problems, it will be harder to reach and engage consumers. For this same reason, there has never been a bigger opportunity for marketing to be a differentiator and as such a critical in house capability.

What Will Happen for Agencies:

In the social era, agencies will need to operate at a pace and scale that bears little resemblance to today’s conventions. Large account structures and months of planning to create and run don’t map to social marketing, real-time campaign modifications and funnel analytics. Strategy and buying remain important, but brands will feel the need to take back some content creation, tracking and optimization – and with it, some agency value. At the same time, much of the residual creative will move to socially distributed content companies such as BuzzFeed and Vice– each of which is investing in audience and distributions tools.

All that said, the bigger problem is structural. Agencies used to focus on the previously key elements of the funnel (awareness) and despite their shift into digital, still are largely organized around TV. While they can no doubt build or buy (they will of course mostly buy) support across the new capabilities, are they truly best positioned to capture value versus the platforms – which provide tech, audience data, targeting, potentially payment processing and fulfillment?

What Will Happen for Platforms:

One of the primary beneficiaries of the funnel transformation will be the major social and ecommerce platforms. They have the ability to provide not just an advertising platform, but a broad stack of funnel capabilities – from audience data and insights to targeting, customer relationship development and engagement, payment processing, and even fulfillment (making Amazon the marketing industry’s sleeping giant). Not only does this stack produce tremendous (and hard to substitute) value for brands, much of this value is clearly defined (which enables platforms to enforce a significant tax). Moreover, by converging these capabilities and eliminating the need for costly creative and account management capabilities, “funnel platforms” can substantially increase the addressable advertiser base. Earlier this year, Facebook’s COO told analysts that through Facebook, “SMBs are able to use the pull of some of the biggest brands in the world. So over 2 million SMBs have posted a video, both paid and organic, in the last month. And that happens to be many times the number of SMBs that have shot or placed a TV commercial.” This value, driven by the expansion of the advertising base, will be monopolized by the major platforms.

However, this same opportunity will put an even greater premium on digital service scale – i.e. the number of users and the amount of data points on them. Just as brand marketing is ineffective if it does not reach enough people, direct is ineffective if it is not properly targeted and tracked. As the two blend, both qualities will be increasingly linked and platforms that can seamlessly serve both brand and direct advertising will find the two businesses to be mutually reinforcing, not cannibalizing. As such, those with both more users and more data and therefore the ability to target and drive purchase will find themselves able to outcompete those who only excel at one part of the funnel. For now, Google is champion of harvesting expressed intent (“Tickets to Hawaii”) while Facebook is king of gleaning latent interest (you don’t even know you want to go to Hawaii yet, but you do). However, with increasing data, better re-targeting and re-engagement, these playing fields will converge and platforms without the ability to do both will be at a disadvantage.

Moreover, as niche brands proliferate, and the ability to target niche communities becomes more valuable, for a platform to reach “scale” it will increasingly need to be so large as to be able to not only serve advertising to a general audience but to serve it to “scaled” niche audiences underneath that umbrella. This of course, will drive up the very definition of what it means to be “at scale” in the first place. Accordingly, “sub-scale” platforms – even those which may seem traditionally massive but digitally modest (e.g. Twitter) and platforms not capable of competing both for brand and direct dollars (perhaps Pinterest)– will struggle to keep up.

Beyond simple scale and data, platforms that can best blend both types of advertising in a single ad unit, plug advertising natively into people’s consumption and allow for direct brand-consumer relationship building will be better positioned as well. In particular, value will accrue to platforms with highly engaging ad units that can seamlessly transition from brand building into direct purchase, while also allowing for direct communication. As Snapchat’s sponsored lenses and WeChat’s stickers highlight, messaging platforms, because they offer advertisers an opportunity for their content to be seamlessly integrated with people’s communications and lives, offer perhaps the most powerful opportunity for brands and branded content to tap into our networks and ride a wave of virality, thereby making them must have channels. In addition, as with Facebook messenger, direct messaging channels, because they are the first media channel to allow brands to create meaningful two-way direct relationships with their audience, will also become increasingly critical. As such, social services without ad units that blend direct and brand advertising, strong native ad offerings and deep hooks into messaging will be disadvantaged. Once again, the definition of being “at scale,” this time in terms of the products offered, has been driven up. As such it is more likely than not that the future will be won by a handful of giants than by an oligopoly of relative equals.

What Will Happen for Media:

As the funnel collapses, media companies will face many of the same problems as agencies. Creating content and thus ad inventory/impressions will always be important, but it will be relatively less important across the funnel as the major distribution platforms focus on end-to-end funnel capabilities (authentication, targeting, user data, payment processing etc.). If you’re an advertiser, where would you ascribe most of the value-add? And even if media’s share remains high, will it replicate its traditional take?

In addition, non-premium, lightly-produced and user-generated content will get a growing share of total media ad spend. Marketers historically put a lot of effort into (subjectively) assessing the quality and brand-adjacency of the content they would advertise beside. However, this focus continues to decline thanks to the rise of programmatic advertising and the overall scarcity of consumer attention. In addition, growth in digital advertising capabilities (not to mention increased advertiser comfort with digital metrics) along with ever decreasing engagement among audiences that matter to advertisers will eventually put an end to TV’s dominant share of national advertising (which has been in place for 25 years). While “Big Media” has a future in digital advertising, they’ve spent decades with a monopoly on the medium that underpinned virtually every ad campaign. In digital – where Google and Facebook own more than half the market and more than 76% of growth – this is unlikely to be replicated. With time, traditional TV ad inventory (which dominates media cash flow) will start to trade at a discount due to its lackluster funnel data and ultimately cede ground as the gap between consumer attention and ad spend closes.

What Will Happen for Consumers:

These changes will be largely positive for consumers. Consumer choice will greatly expand, especially when it comes to products targeting specific tastes, demographics and backgrounds. The industry’s “competitive carrying capacity” will be expanded immensely. Despite this, it’ll also be easier than ever for consumers to find, try and embrace new brands. If the physical world was defined by the catalogue, and the internet era was defined by the search bar, the mobile era will be defined by recommendation and curation.

Sale: Now

Since the dot com boom, the promise of the internet in fundamentally changing distribution, marketing, advertising and consumption has never fully lived up to the hype. While the major web services sucked the air out of classifieds and newspaper advertising, digital seemed unable to truly slay the beast that is TV advertising. And although consumer choice became more plentiful, the process of shopping for, purchasing and receiving products did not change as much as many had hoped. We still lived in an age determined and defined by the limitations and inefficiencies of the marketing funnel. But the rise of new distribution and marketing channels, on-demand infrastructure and consumer tracking stands to dramatically reshape this funnel, collapsing it in on itself, opening up new battlegrounds for brand competition and ushering in significantly more consumer choice. Time to get shopping.