Driving through the outskirts of Corona, California, you’re confronted with one grey low-rise office park after another. Indistinguishable companies selling widgets and signs and accounting services blend into the monotony of suburban America. But one of these bland office parks happens to be the production facility for the company that helped define rock and roll with the first mass-produced electric guitar.

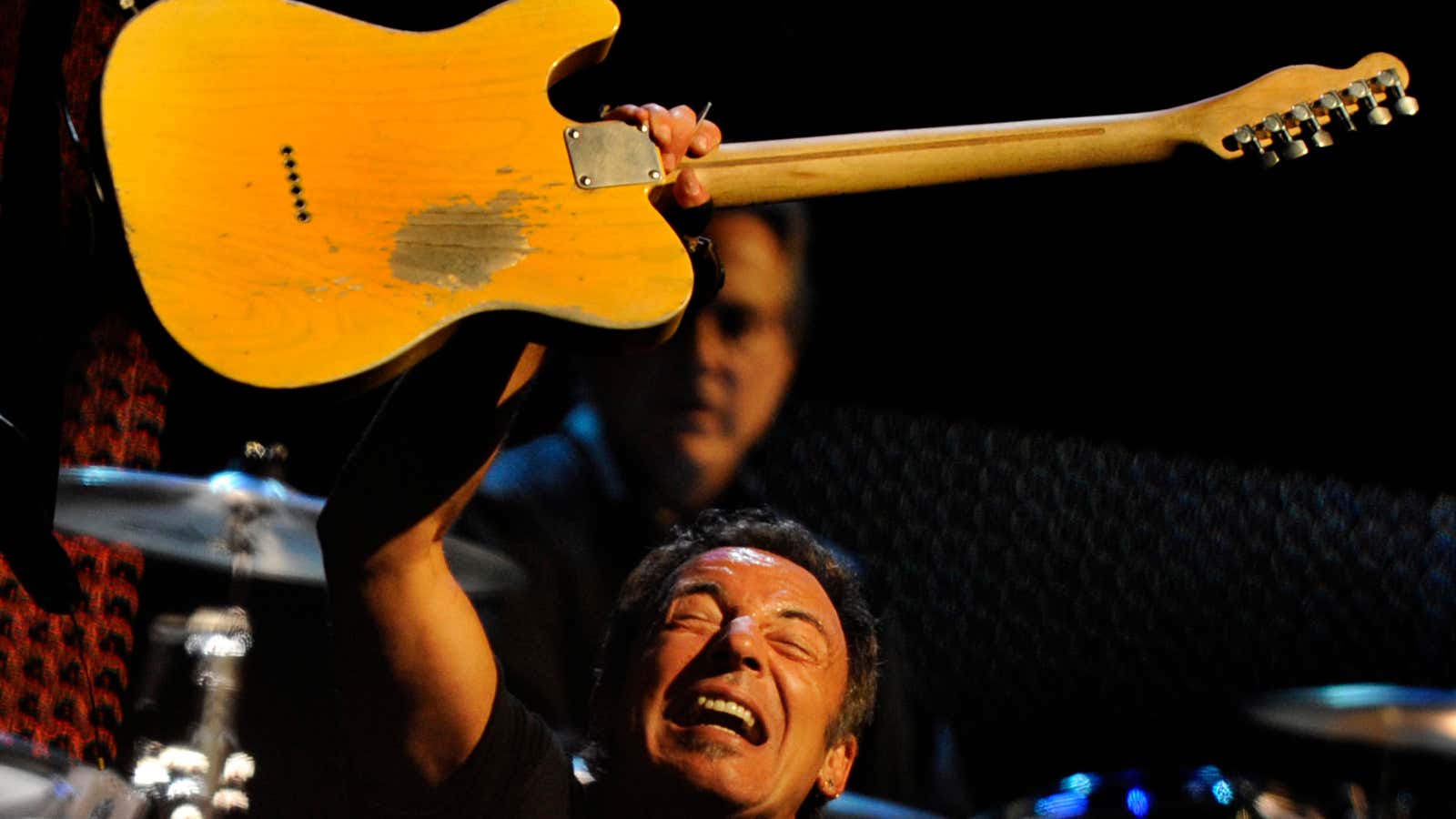

Fender has produced some of the most recognizable instruments in modern music, with designs that have stood the test of time. Founder Leo Fender—an electrical engineer by trade—borrowed the prevailing trends of hot-rod cars from the late 1940s and ‘50s to design the Stratocaster, Telecaster, Precision Bass, and Jazz Bass, to name just a few of his company’s most famous designs. Although refined ever-so-slightly over the years, these instruments’ designs have remained vastly unchanged since they first rolled off the production line when Baby Boomers were still a glint in their parents’ eyes.

Music has undergone myriad tectonic shifts in style, trends, and production techniques since the Stratocaster went into production in 1954, but Fender has generally rolled with the changes. Still though, the company has been known for the quality of its wholly analog products—guitars that in some cases still have wax capacitors in them, and amplifiers still relying on vacuum tubes (the precursor to the transistor)—at a time when much of the way that the world produces and consumes music is entirely digital.

Depending on who you ask, guitar sales are either withering or experiencing a renaissance. The reality is likely somewhere in the middle. The electric instruments associated with rock music—a genre no longer dominating music charts like it used to—are flagging, whereas newer electric-acoustic guitars, like those played by pop stars Taylor Swift or Ed Sheeran, are selling to young budding musicians the world over.

In 2015, Fender brought on Disney and Nike veteran Andy Mooney as CEO to address these trends. How do you keep an American icon ticking along, while also trying to address the desires of tomorrow’s players?

When Mooney was still at Disney, he met with then-CEO of Pixar and co-founder of Apple, Steve Jobs, Mooney said. Jobs had told him, in his mind, that every single product a brand produces is “either a deposit or a withdrawal in the brand’s equity.” When he started at Fender, Mooney said he saw the company’s electric guitar and amp products as deposits in the Fender brand bank. “Other categories—acoustics, pedals, generally anything else in the signal chain—I felt we could improve,” he said. Mooney added that in the intervening years, the company has become a “serious player” in pedals and acoustic guitars, and it’s breaking new ground apart from instruments. “On the digital side we’re both creating new businesses and the businesses are synergistic to a core in the sense of helping group grow the entire industry.”

Fender is trying to do both things at once, and for now, it seems to be succeeding. In 2017, it launched Fender Play, a new subscription service that works on multiple devices to teach people how to play guitar. The app, which features content from popular musicians like The Rolling Stones, The Foo Fighters, and Carrie Underwood, is meant to help aspiring guitarists learn the music they want to play. At the launch, Fender’s head of digital products, Ethan Kaplan, said that 90% of guitar players give up after a year. It’s a frustrating instrument, and not immediately being able to emulate your heroes can be disappointing to new players. Play helps without the judgement of a teacher, and with songs they actually know. Mooney said if Fender were able to cut that drop-off rate by 10%, it would have profound impacts over the lifetime of the player, and for the guitar industry. The app has 110,000 paying subscribers, as of October.

Earlier this year, Fender released another innovative app, aimed at the players who are a little further along on their learning journey, called Fender Songs. The new $5 per month app, currently built atop Apple Music, uses machine learning to help users to learn how to play it. Players can listen to a song, slow it down, and see the chords that are being played as they happen—rather like Guitar Hero, but in real life and you’re playing on an actual instrument. Doing this for your favorite song either used to take hours of patience and trial-and-error while listening to the song, or hoping you could pay $20 for a copy of the sheet music—assuming you could read music. Mooney said he’s learned about 150 songs in the 50 years he’s been playing guitar—currently the Songs app has a library of 750,000 to choose from.

And this is just the start of how the company hopes to retain new guitar players and entice prospective learners. “I think the more that we can do to help guide people through the buying decision, and then I think the better off everyone will be because there’s more likelihood that the first-time player will stick with it,” Mooney said.

While Fender has been doing direct-to-consumer guitar sales in the US for about five years, Mooney said they only make up about 2% of the region’s revenue. Guitars are generally things you want to feel and play before committing to buying one, and the easiest way to do that is still in person. But most stores are hardly welcoming for new players—especially women. “I describe a lot of the music stores as a club that you only get to join if you’re already in it,” Mooney said. The answer will be to educate buyers to feel more empowered when they go in and deal with the annoying sales clerk at the guitar store. “There’s so much we can do in social media for things like, new buyers’ guides,” Mooney suggested, “or how to get great tone out of an amp, or answering simple questions like, ‘What’s the difference between a Stratocaster and a Telecaster,’ which we think everybody knows—they don’t.”

But as it builds out its digital presence, Fender is trying to straddle generations. At its factory in Corona, which primarily concentrates on the company’s higher-end and custom models, there is little evidence of the young, vibrant, app-producing company that unveiled Fender Songs at a loft apartment in New York earlier this year. The factory is a place steeped in the decades of tradition of the company. Although the current factory was only built in 1998, Fender has been producing guitars in a smaller facility in the area since 1987—the company was sold to a group of investors, including its then-CEO William Schultz, by CBS in 1985, but the sale didn’t include the factory Fender had been operating out of since 1953—and much of the machinery in the factory dates back to before the Vietnam War.

Fender’s most recent electric guitar line, the American Ultra series, is packed with technology that the company has called “subtle yet crucial innovations.” For example, the new guitars were designed with revamped ergonomics that actually take into account the shape of the human body, meaning the guitar sits comfortably against you while playing it, which no blocky pieces of wood or metal that have been sticking into guitarists’ rib cages or stomachs for decades. The guitars also feature a button hidden in the volume knob that changes the sound of the guitar, by combining or separating pickups on the guitar.

Similarly, Fender’s electronic amplifier division is putting out guitar amps that, using custom software and a ton of onboard processing power, sound indiscernible from its amps that use vacuum tubes. The software and electrical engineers working on these new amps, referred to as the Tone Master line, actually sit right next to the team that builds the traditional amps, Fender’s evp of products, Justin Norvell, told me, so that they can check whether the sounds they’re producing are as authentic as the ones produced by tube amps.

But building all of these instruments and accessories is still a very manual process. The Corona factory produces most of Fender’s high-end and custom guitars, and can produce a few hundred instruments per day. While some parts of the building process are aided by longstanding computer-aided technologies—like CNC milling machines used to cut the basic shape of a guitar out of wood—the guitars are still hand-sanded, their fretboards crafted with individually hammered-out pieces of metal. Many women work on the factory floor at the plant, as their hands are generally smaller and more adept at some of the more dextrous tasks required to build a guitar.

One woman, Josefina Campos, spends every day hand-wiring the electric pickups used in just about every guitar built by Fender’s custom shop. She has sat in her own well-appointed office, customized by her to feel more welcoming and replete with a bowl of candy for visitors, for over 20 years, having joined the company in 1991 as a guitar sander. She learned her trade from Abigail Ybarra, who retired in 2017 and who was taught by Leo Fender himself how to wire pickups in 1958. Campos signs every pickup of hers that makes it into a Fender guitar.

On the factory floor, there are other signs of the company’s heritage and ingenuity. A volume knob from a Telecaster is used in one machine to flatten out fretboards after the original tool broke; old firehoses are used to press together wood for guitar necks; a rack on the ceiling of the factory that was originally intended for drying painted guitars now holds excess inventory. There are hulking, green machines with paint stripped down to their silvery innards where decades of workers have laid their hands while using them. The original guitar produced by Leo Fender, a prototype of the “Broadcaster” (which due to a copyright battle ended up being called the Telecaster), hangs in a hallway, accompanied by other famous instruments produced by the 73-year-old guitar company.

But at the same time, there are glimpses at a more technical future. The wood for guitar bodies is aged and humidified in temperature-controlled racks that are linked up to sensors connected to an Amazon Web Services dashboard that managers can access from their phones wherever they are. If anything goes awry, they can find out instantly, not when someone next decided to check on the wood. “If you didn’t put the country of origin on a guitar, you probably could have told the difference from the US, Mexican, or a Southeast Asian model,” Mooney said. “That’s not as easy to do anymore because the quality of all three of gone up.”

Fender is trying to merge its traditions with the direction music is going. It no longer takes generations for music genres to emerge, or culture-defining artists to top the charts. Spotify, YouTube, Soundcloud, and social media have made it easier for anyone to be recognized for their talents near-instantly. Creating instruments and technologies that are as flexible as the music people want to create is a difficult task, as is making money doing that. But Mooney is optimistic, telling me that the company’s Mustang amps are now the best-selling digital amps in the world, and adding that technology helping the business in unexpected ways. The amps have companion apps that let players tune to custom presets, and Fender has all the data on what’s most popular. “It tells you something about the profile of someone who’s buying a digital amp as opposed to a tube amp,” he said. “It was designed as a companion to the product, but it’s giving a whole bunch of info on how to evolve the product.”

Mooney said he envisions in the future that the app, called Fender Tone, could end up “being a standalone thing,” where an amplifier isn’t even in the mix and a user plugs their guitar right into a computer, pulls up the preset they’re after, and starts recording without anything else. Looking ahead, Mooney said he expects software to play an outsized role in the company’s successes. It’s growing from nothing, so any increases in the short term will look massive, but he conceded that within the next five years, Fender’s hardware sales will still make up the bulk of its revenue. With Songs, Fender not only has to give Apple its 30% App Store cut, but also pay the artists whose songs users are listening to. “So the profit margins on these apps for us is probably less than other people who are starting meditation apps or something like that,” Mooney said. Overall, the company has grown by “high single digits, low double digits” each year that Mooney has been in charge, and he said he expects that to continue this year.

Whether much will change for Fender’s sales will depend on if it can keep new musicians to keep playing, and for more experienced players to want increasingly fancy instruments. But what’s likely not going to change, at least not very much more, will be Leo Fender’s iconic designs, which have endured every cultural shift the world has been able to throw at it. They are a platform like another other product, that lets you do with them whatever you want.

“I think why these designs have survived the test of time is that form follows function,” Mooney posited.