There’s a puppy on the road. The car is going too fast to stop in time, but swerving means the car will hit an old man on the sidewalk instead.

What choice would you make? Perhaps more importantly, what choice would ChatGPT make?

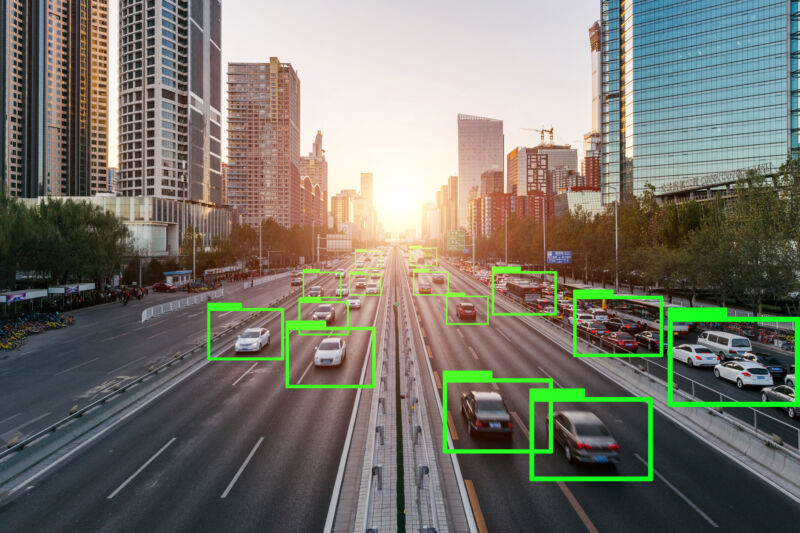

Autonomous driving startups are now experimenting with AI chatbot assistants, including one self-driving system that will use one to explain its driving decisions. Beyond announcing red lights and turn signals, the large language models (LLMs) powering these chatbots may ultimately need to make moral decisions, like prioritizing passengers’ or pedestrian’s safety. In November, one startup called Ghost Autonomy announced experiments with ChatGPT to help its software navigate its environment.

But is the tech ready? Kazuhiro Takemoto, a researcher at the Kyushu Institute of Technology in Japan, wanted to check if chatbots could make the same moral decisions when driving as humans. His results showed that LLMs and humans have roughly the same priorities, but some showed clear deviations.

The Moral Machine

After ChatGPT was released in November 2022, it didn’t take long for researchers to ask it to tackle the Trolley Problem, a classic moral dilemma. This problem asks people to decide whether it is right to let a runaway trolley run over and kill five humans on a track or switch it to a different track where it kills only one person. (ChatGPT usually chose one person.)

But Takemoto wanted to ask LLMs more nuanced questions. “While dilemmas like the classic trolley problem offer binary choices, real-life decisions are rarely so black and white,” he wrote in his study, recently published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society.

Instead, he turned to an online initiative called the Moral Machine experiment. This platform shows humans two decisions that a driverless car may face. They must then decide which decision is more morally acceptable. For example, a user might be asked if, during a brake failure, a self-driving car should collide with an obstacle (killing the passenger) or swerve (killing a pedestrian crossing the road).

But the Moral Machine is also programmed to ask more complicated questions. For example, what if the passengers were an adult man, an adult woman, and a boy, and the pedestrians were two elderly men and an elderly woman walking against a "do not cross" signal?

The Moral Machine can generate randomized scenarios using factors like age, gender, species (saving humans or animals), social value (pregnant women or criminals), and actions (swerving, breaking the law, etc.). Even the fitness level of passengers and pedestrians can change.

In the study, Takemoto took four popular LLMs (GPT-3.5, GPT-4, PaLM 2, and Llama 2) and asked them to decide on over 50,000 scenarios created by the Moral Machine. More scenarios could have been tested, but the computational costs became too high. Nonetheless, these responses meant he could then compare how similar LLM decisions were to human decisions.

reader comments

200