Growing up in Colorado, my indoctrination into the beating heart of skiing happened at Arapahoe Basin. Nestled against a rugged section of the Continental Divide an hour’s drive from Denver, A-Basin was a playground at the top of the world. On “the beach”—an open stretch of snow between the parking lot and the lifts—skiers cavorted over pony kegs and hibachi grills. Reggae played. Dogs bounded in the snow. Grizzled old-timers regaled newbies who had bought discounted lift tickets at the local King Soopers. In the spring, flamboyant costumes colored the slopes, and amateurs competed in events like the Enduro—two-person teams skiing as many double-black laps on the rickety Pallavicini Lift in 10 hours as possible to raise money for a community member in need. There was camaraderie, freedom, community, and lots and lots of fun.

Skiing looks different in much of North America today. That’s because it has been reduced to a binary choice: Epic or Ikon?

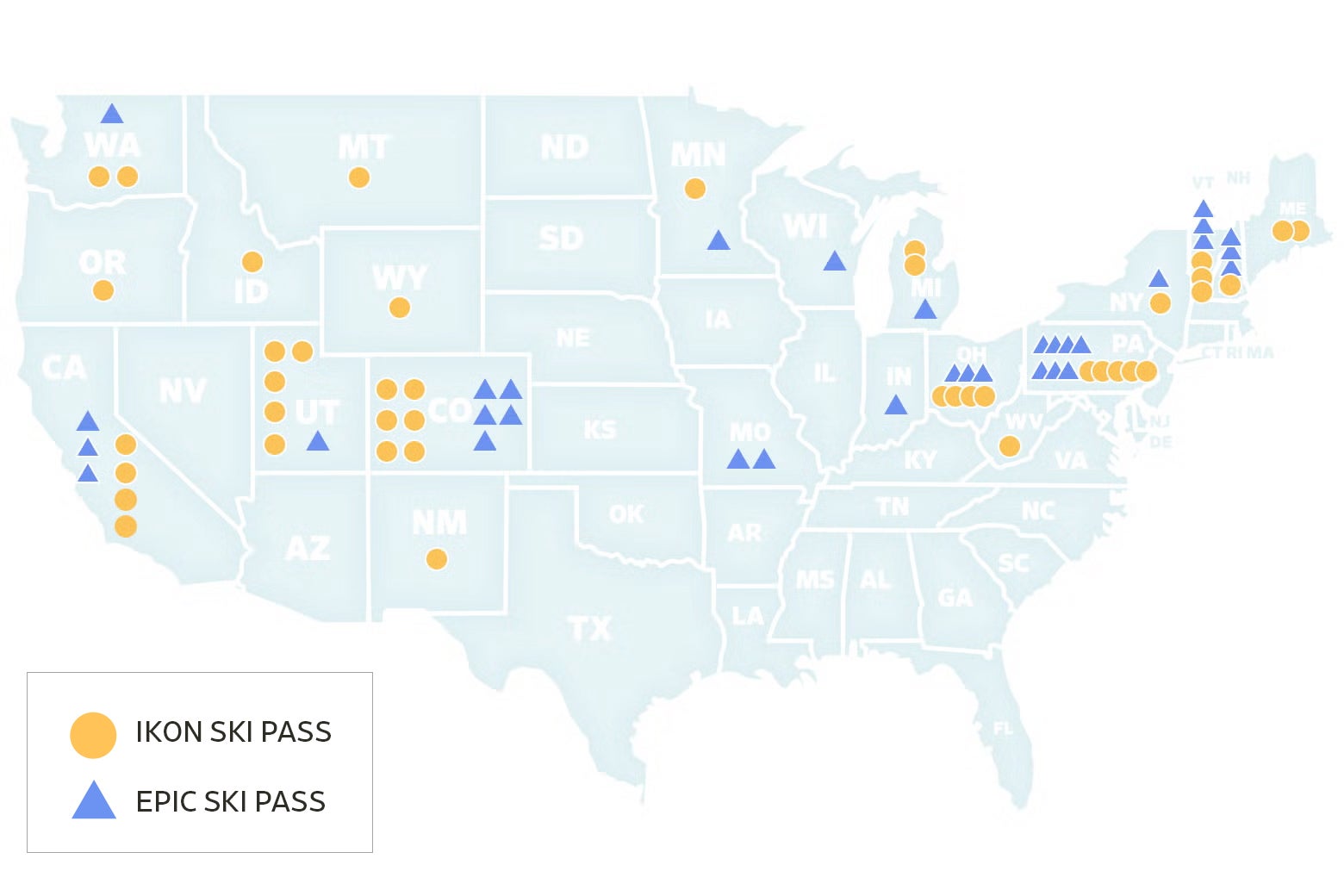

The Epic Pass (offered by Vail Resorts, $909 early-bird) provides varying levels of access to 80 ski areas on four continents, from Podunk hills in Missouri to world-class peaks in the Rockies. The Ikon Pass (Alterra Mountain Company, $1,159 early-bird) has a similarly impressive and globe-spanning repertoire of 55 areas. Vail and Alterra are in an arms race for acquisitions and partnerships with no end in sight. Skiing, like personal computing, credit cards, and soft drinks, is now a duopoly.

On paper, the industry looks healthier than ever: Last year was the busiest ski season in U.S.

history, with visits up 6.6 percent to 65.4 million days skied, driven by record Epic and Ikon sales. But behind the numbers, a familiar tragedy is unfolding. High-spending pass holders may be getting a bargain, but all the other prices, from single-day tickets to ski school to housing, have skyrocketed. Locals are being forced out and workers squeezed. The new business model is attracting jet-setters and displacing ski bums. Mountains are losing their culture as the same two companies take over lodge after lodge after lodge. Gone are live bands, independent outfitters, free lift-side parking, and secret smoke shacks. Skiing has fast become just another soulless, pre-packaged, mass commercial experience.

The story of how this happened begins, unsurprisingly, with private equity. In the early 1990s, Leon Black’s Apollo Capital Management bought the company that owned Vail and Beaver Creek, two of Colorado’s finest ski areas, out of bankruptcy. Apollo took the company, restructured and rechristened as Vail Resorts, public in 1997 and immediately set off acquiring resorts, retailers, dining venues, and upscale-to-luxury hotels, vacation rentals, and condos across North America, plus in Australia and Switzerland. Today, Vail is an $8.6 billion empire with 42 resorts and hundreds of other holdings.

The engine of Vail’s expansion has been the multimountain season pass. First was the Colorado Pass, which granted 10 days at Vail or Beaver Creek and unlimited access to Keystone, Breckenridge, and A-Basin (a non-Vail-Resorts-owned partner). In 2008, Vail debuted the Epic Pass, which included Heavenly in Lake Tahoe. Each year, Vail added new acquisitions and partners onto the pass. It purchased small mountains near New York, Boston, Chicago, and other population centers to funnel well-off vacationers to premier resorts out West, such as Whistler, Vail, or Park City, where the company also happened to own the lodging, retail, and dining infrastructure. Pass sales locked in revenue pre-season, an increasingly valuable hedge as climate change makes snowfall less certain. Vail’s annual revenue tripled from $940 million in 2007 to $2.8 billion in 2023.

With Epic, Vail quickly eclipsed Intrawest, a Denver-based rival that since 2003 had been offering a competing pass to Copper Mountain and Winter Park. By 2017, someone there must have realized they needed to put up a fight: Soon, the private equity firm KSL Capital Partners joined forces with the owners of Aspen to purchase Intrawest. The new conglomerate, Alterra Mountain Company, launched the Ikon Pass with 23 destinations in nine states and Canada. The duopoly was born.

For skiers, the passes are an irresistible deal. In the ’90s, a season pass to a single ski area could go for $2,000 (inflation-adjusted). Now, for half that price, you can ski several world-class mountains all over the world. Thanks to an inexcusably permissive class schedule my senior year of high school and the then-still-novel Colorado Pass, I logged 70-plus days for a grand sum of $349—an unbeatable five bucks an outing. This kind of value has led proponents to declare that Vail and Alterra have made skiing more accessible than ever.

But accessible for whom? For a recreational skier of means in Brooklyn who can front a thousand bucks well before the start of the season, a pass does indeed open up new possibilities. The story is different, though, for a working dad in Denver who wants to take his kid up to Breckenridge for a day in late December to try out skiing. He will find that everything that is not a season pass is criminally expensive. Parking is $20; his lift ticket $251 (online—at the window it’ll be $279); basic rental gear $78; burger, fries, and a Gatorade for lunch $35; end-of-day Coors Light $8; and $418 for the kid’s rental, ticket, and group lesson (at least the lesson includes lunch). All in, an $800-plus day.

Breckenridge is owned by Vail Resorts, but even independent partners tend to adopt a similar pricing structure to encourage pass purchases. In 2016, the year before it joined Ikon, Eldora, a small mountain outside of Boulder, charged $84 for a single-day ticket and $99 for a day of youth ski school. Today, a lift ticket is $169, ski school $269. Inflation is not that bad.

Even the teenage ski bum I once was would struggle to love today’s Epic Pass. Swarms of pass holders have made weekend traffic and lift lines intolerable. And staying overnight in the mountains is prohibitive, as upscale developments and influxes of out-of-towners have sent lodging and housing prices into the stratosphere. In Avon, where resort workers who couldn’t afford nearby Vail tended to live, the median home price tripled from 2015 to 2023, according to Zillow, four times the national increase during that period.

Workers are struggling under both rising costs and the extractive private equity model.

Vail Resorts recently faced two class-action suits for failing to compensate employees for breaks, meetings, training, and equipment purchases. Only in 2022, after more ski patrollers unionized and pandemic staff shortages crippled operations, did the company raise its minimum wage to $20 per hour. And yet, Vail’s CEO was compensated $6.2 million in fiscal year 2023, a sum 243 times greater than the median employee pay ($25,538), according to the company’s annual report. (As a private firm, Alterra does not disclose the compensation paid to its CEO, who is the former president of Ticketmaster.)

Less quantifiable but just as real is the damage being done to the spirit of skiing. From Crested Butte to Park City to Whistler, locals rage about how corporate ownership has ruined the culture and community of their mountains. High-end chains replace independent retailers. Local lift ticket deals vanish. Dirtbags become rare among crowds of the super-rich. Corporate policies ban barbecues, spontaneous après-ski parties, and mohawks or long beards on lift operators. As the duopoly grows, the playful irreverence and fellowship that constitute skiing’s soul recede.

For years, ski romantics like myself have watched the march of corporate consolidation with feelings of anger, resignation, and complicity. We hate what Vail—Alterra, too, but Vail especially—is doing to skiing. And yet each fall, we consult with friends, plan trips, and pick a pass to buy. What other choice is there? Almost every good mountain is claimed. Unless we move to Alaska, we’re stuck with the new “Pepsi or Coke” of the ski world.

Seeing all this happen provokes a futile outrage common in modern American life. We decry Amazon’s size and labor practices, yet we are all still Prime members. Airlines nickel and dime us while providing worse service, but what are we going to do—not fly? The structure of the ski industry transcends individual choice. Changing it would require the companies and ski areas to value something besides just growth and profit.

There are glimmers of hope though. Despite being on a Vail multimountain pass since 1997, A-Basin had always managed to keep its spirit and culture. But as the Epic Pass grew, crowds were overwhelming the mountain. Parking lots were full by dawn. The vibe became tense. So in 2019, A-Basin did the opposite of what every other ski area was doing: It left the Epic Pass. It began offering its own season pass (and allowing seven days on Ikon).

In the 2022–2023 season, A-Basin had 40 percent fewer visits than it did in 2018. Yet the mountain was profitable. The Enduro raised thousands of dollars for a 37-year employee recovering from cancer treatments. And when I visited on a $92 single-day ticket, the beach was as fun and lively as ever.