A.I. image generators are divisive. But few can deny that they have gotten really good. Within seconds, you can type in a prompt to make a photorealistic image of Donald Trump getting arrested or turn your strangest idea into something tangible.

Over the coming years, A.I. companies will release even more advanced models that will remind us that this is just the beginning. At least one of these tools will be different in an important way: It will be prohibited from seeing 80 million of the images that helped teach its predecessors to draw and paint. If you think of A.I. image training sets as lesson plans and word-to-image tools like DALL-E and Stable Diffusion as college students, it’s kind of like saying that incoming freshmen are prohibited from taking one of the outgoing seniors’ core requirement classes. Why? Because two Berlin-based musicians persuaded the head of a multibillion-dollar company to give artists more power.

Many illustrators, designers, and photographers are furious that their work had been scraped from the internet to train an A.I. Last September, Mathew Dryhust, an artist and academic, and the experimental electronic artist Holly Herndon, created HaveIBeenTrained, a tool that enables you to see if your images have been used and then request that future A.I. models avoid them. It recently became clear that this was more than a subversive art project when the CEO of the company behind Stable Diffusion, one of the most widely used A.I. image generators, gave people a March 3 deadline to opt out using Herndon and Dryhurst’s tool. Millions of requests poured in, Dryhurst told me. As of this week, around 40,000 artists and many companies, including Shutterstock, a major image distributor, have opted out.

“It’s very common in a lot of art circles where people are like, ‘I wrote an essay or a video about my cool idea,’ ” said Dryhurst. “And we’re like, ‘No, why don’t we just build the thing?’ ”

The project raises some uncomfortable questions about the rapidly evolving world of A.I. content creation. Mainly: Is this the best way to bring order to the Wild West of image scraping? And also: If companies go along with these opt-outs, are they really the good guys, or should they have avoided copyrighted images in the first place?

For some people, the pandemic was a time to master sourdough. For Dryhurst, it was a time to see what artificial intelligence knew about his wife. In order for an A.I. tool such as DALL-E, Stable Diffusion, or Midjourney to conjure up your look—without you feeding it reference images—you need to “meet a certain threshold of notoriety,” Dryhurst explained to me over Zoom a couple of weeks ago from his home studio in Berlin. (Herndon was busy with their 3-month-old baby in the other room.)

Dryhurst does not himself meet that threshold.

Type “Mathew Dryhurst” into DALL-E, and you get three athletes and a long-necked aspiring mayor:

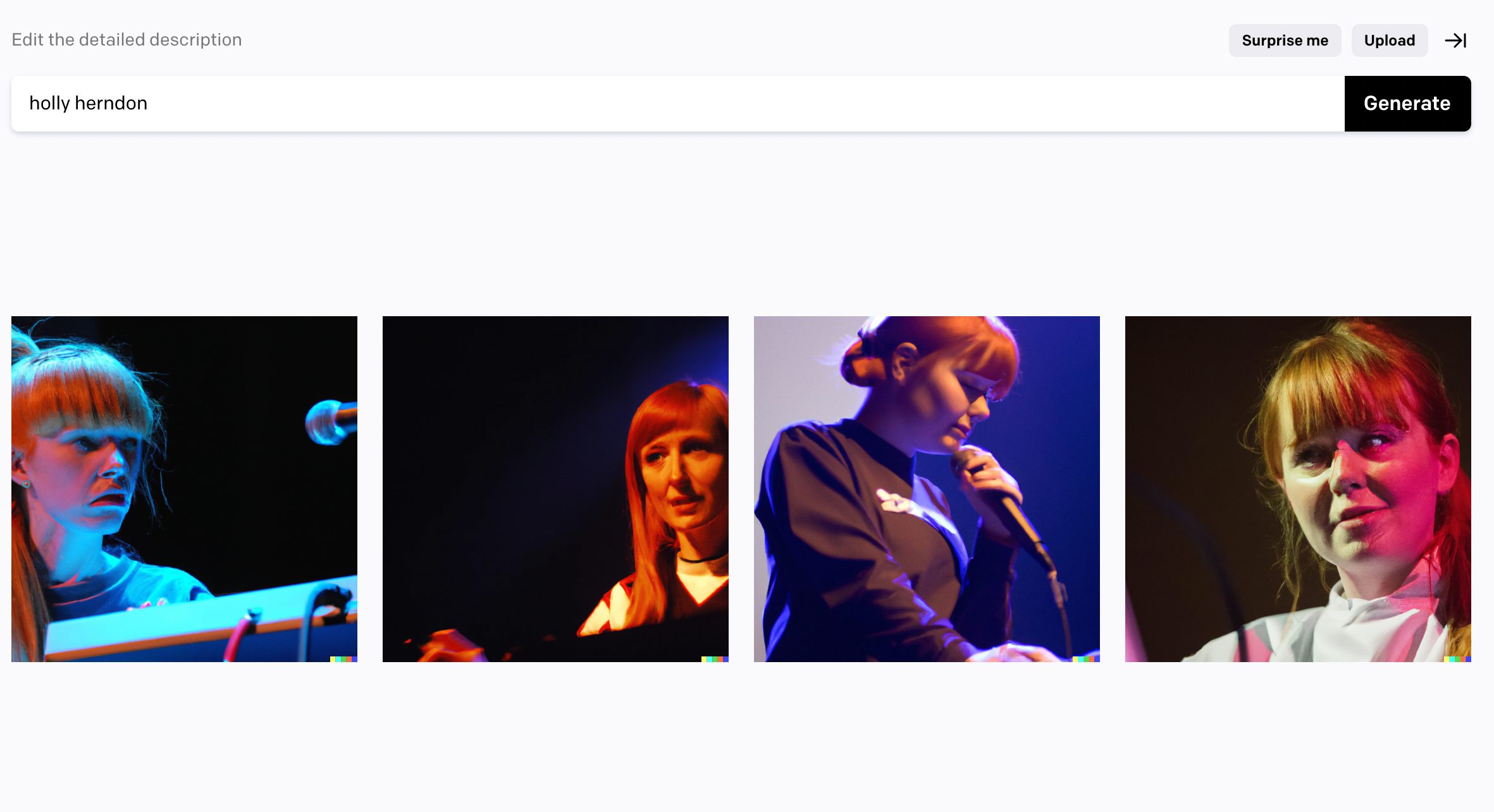

But, as Dryhurst correctly predicted, Herndon is the A.I. version of Googleable.

Here’s Google Holly:

And here’s DALL-E’s Holly, with her signature ginger hair.

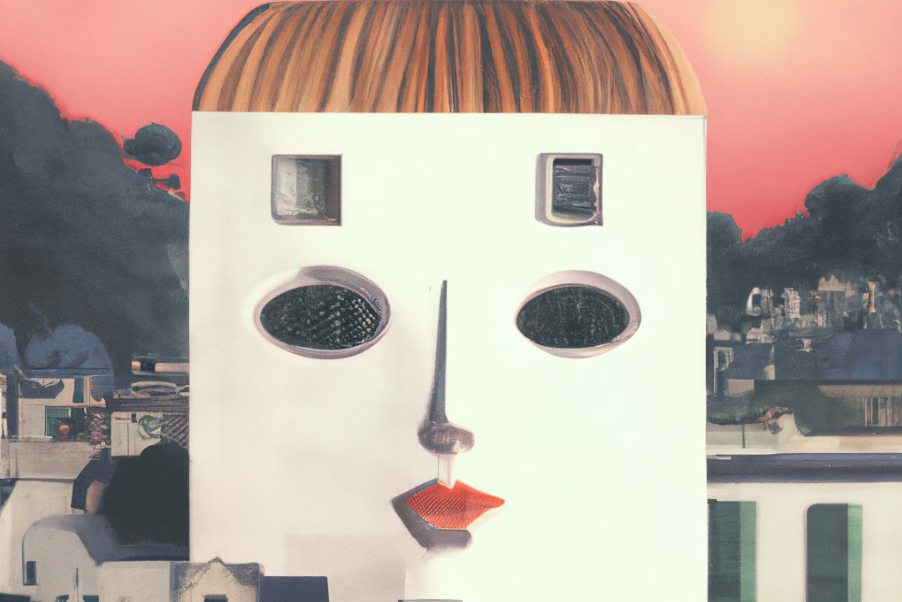

Herndon has a Ph.D. from Stanford University’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics and has been praised by many an outlet for somehow creating club bangers that raise profound questions about neural networks. Perhaps just as impressively (or disturbingly, depending on your vantage point), when you type “a building that looks like Holly Herndon” into CLIP, a predecessor of DALL-E, you get a white apartment building with her bangs.

When Dryhurst saw this image , he thought, “Oh dear.” Not because the couple felt helpless. (Herndon went and created a self-portrait series using CLIP, which Pussy Riot auctioned at Sotheby’s and another site sold as NFTs.) It was because he correctly predicted that an ethical tsunami was about to hit. Throughout 2021 and 2022, several companies released tools that were even more advanced and accessible than CLIP. People who’d never had any interest in A.I. discovered that they could type in an artist’s name and not just reproduce their haircut but draw or paint in their style. Suddenly, everyone wanted to know: What had the machines been studying?

Dryhurst and Herndon, along with several engineer collaborators, created a new company called Spawning to help artists take control of their A.I. identities. Their first project, the HaveIBeenTrained tool, makes it easy to search through the billions of images within LAION-5B, an open-source training set that is used, for example, by Stable Diffusion. (Other popular A.I. tools use proprietary training sets that would not be searchable in the same way.)

Iris Luckhaus, an illustrator based in Berlin, was one of many artists who turned to HaveIBeenTrained in December, soon after Lensa’s I’ll-turn-you-into-a-hot-superhero app hit the top of the app charts. She wondered whether her own illustrations had helped train Stable Diffusion, the A.I. model Lensa relied on. Indeed, through the tool, she learned that 3,280 of them had, including early drafts of illustrations that she hadn’t realized were findable on the internet.

“I felt violated and terribly angry,” Luckhaus said. Just because she puts artworks online, that’s “not an invitation to just do with them as you please”—in this case, to create a tool that she is concerned will replace human artists. She refuses to use A.I. image generators because exploiting other artists makes her feel just “as dirty as buying cheap clothes made with child labor,” she said.

Dryhurst and Herndon are OK with allowing A.I. models to study their own images, but they feel that consent is important, so they added an opt-out feature to HaveIBeenTrained. Of course, that was useless without an agreement from an actual A.I. company to abide by their rules. They picked Stability AI as an initial target partly because the company had created Stable Diffusion, one of the most popular A.I. image-to-text tools on the market. Within two months of Stable Diffusion’s August 2022 debut, it had more than 1 million users, and 200,000 developers had licensed the software to make their own image-creation apps and tools. In October, Stability AI raised $101 million. (The company is currently seeking to raise money at a valuation of $4 billion, according to Bloomberg.)

Emad Mostaque, the founder and CEO of Stability AI, agreed to abide by their rules. “We think it would be really a very powerful gesture for you to, in advance of training another model, respect any claims that came in,” Dryhurst said he told him. And perhaps partly because they have friends in common, Mostaque responded with something like “Yep, that’s cool.” And that’s how two creators who are best known for wild, technology-subverting art experiments came to be two of the official gatekeepers of our A.I. art future.

Herndon and Dryhurst show how “new collective structures” can fill a void left by the absence of clear A.I. laws or government oversight, Paul Keller, the director of policy at Open Future, a European think tank focused on digital policies, recently wrote. Eric Wallace, an A.I. researcher and Ph.D. student at the University of California, Berkeley, called Spawning’s work “significant” and said it shows that a “power-to-the-people mindset” can shape policies in the rapidly advancing A.I. space. (Wallace was involved in a recent study that demonstrated that popular A.I. tools can be prompted to spit out exact copies of copyrighted artworks.)

Not everyone is as complimentary. The musicians simply created a system for thieves to return stolen goods, some argue; A.I. companies should train their tools on images that people have chosen to opt in, not put it on artists to opt out. “Being able to plagiarize a work just because the artist didn’t find this campaign is absurd,” one photographer, who goes by @Withanhmedia on Twitter, wrote. Artist manifestos and lawsuits make a similar point. In February, Getty Images, which is notoriously protective of its images, sued Stability AI, arguing that by copying more than 12 million of its images, the company had committed “brazen infringement” of intellectual property.

The second critique says that it’s too late to get A.I. tools to unsee artistic influences, since the current models are already being used. In a twist on this, Christoph Schuhmann, one of the founders of LAION, told CNN last year that opting out is useless unless the entire A.I. industry respects requests. (LAION has not yet formally agreed to remove opted-out images from future training sets; only Stability AI has.)

Still others say that Spawning, a tiny company, is not equipped to be the world’s official A.I. referee. Yes, their free tool makes it easy to opt out—or, another feature, opt in—images, but verifying identity is a huge undertaking, they say. (Spawning says it’s fine-tuning its system.)

A rather different rebuttal to the effort is that there’s no legal basis to give artists any kind of control over whether machines study their work because, as Peter Kafka of Vox summed it up: “There’s no law against learning,” and “turning one set of data—even if you don’t own it—into something entirely different is protected by the law.”

Alongside these arguments, you’ll find artists like Neil Turkewitz, a copyright activist, who praised the Spawning endeavor on Twitter while also arguing that it’s best to see it as “a step towards accountability and not the destination.” Luckhaus agrees that the realm of training sets needs regulation as well, but for now, Spawning is the only endeavor offering her a concrete way to protect her images. For that, she is grateful.