Para leer este artículo en español, oprima aquí.

In 2012, Mia Phillips got the kind of opportunity most people only dream of. For years, Phillips and her husband had visited Crested Butte, Colorado, for mountain bike vacations, getting their fix of alpine views and lung-busting climbs before heading home to a hot and sticky Missouri summer. But that year, in the midst of a career change, she received a scholarship to Western Colorado University, just south of the remote resort town, and her husband, who worked from home, was game to move. The scholarship provided a practical, adult reason for the parents of two, whose girls were also mostly grown, to make the change—the youngest could finish her senior year of high school in Crested Butte. But the real motivation was the ready access to over 700 miles of singletrack, spooling out from a town that claimed to be a birthplace of mountain biking. “We moved,” Phillips says, “because I wanted to ride my bike more.”

That’s exactly what she did. The summer she arrived, Phillips got a job at a biology research station nestled in a high alpine valley near the start of the famed Trail 401. If the weather was nice, she could ride her bike to work, then rip the 401 through wildflower meadows and aspen groves before riding home. Now she felt like she was on permanent vacation.

Life was vacationlike in other ways too. In Missouri, Phillips had enjoyed the occasional drink or two after a ride, but in Crested Butte this was standard practice, and not just relegated to the parking lot; friends brought beers in their fanny packs to savor on the trail. Even if she rode alone, she could head down afterward to “the Brick,” as the locals affectionately called a popular pizza restaurant, and run into friends who were finishing rides of their own. Unlike in Missouri, where there was always a reason to head home after a beer or two—kids to supervise, work to get up early for—in Crested Butte, everyone seemed to be in permanent vacation mode too. There was always a friend who was game for another round, and home was just a wobbly bike ride away.

Phillips was riding more, but she was also drinking more. She gained 20 pounds in spite of all the extra saddle time. Every social event involved bikes, and every bike event involved alcohol, from local dig weekends to the costumed townie tour that raised funds for a local nonprofit. Even on nights she came straight home, she cracked the fridge for a beer, or more.

No one, least of all herself, was counting at the time, but over the years she began putting away startling amounts of alcohol. On a weeknight, she could finish a six-pack. At an event like Crested Butte’s legendary chainless downhill race, she and her friends might arrive on Kebler Pass at noon, drink until the race departed at 4:20, and then stop for a beer midway down, totaling eight or 10 beers over the course of the day. This all seemed normal in a town where many locals simultaneously partied and pulled off casual athletic feats, and Phillips got used to waking up with a hangover and riding it off too. But eventually, she noticed, she wasn’t riding it off like she used to.

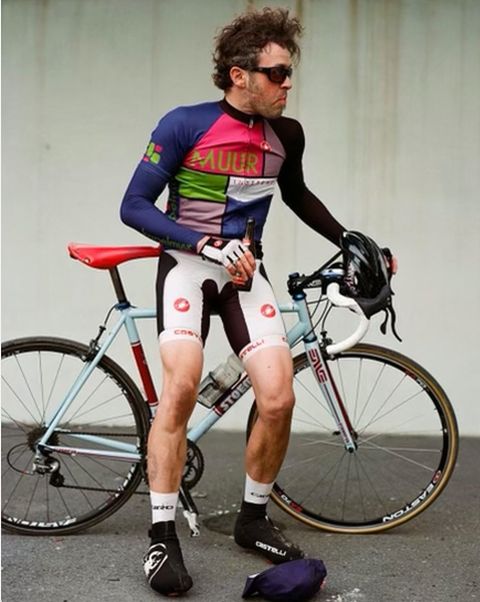

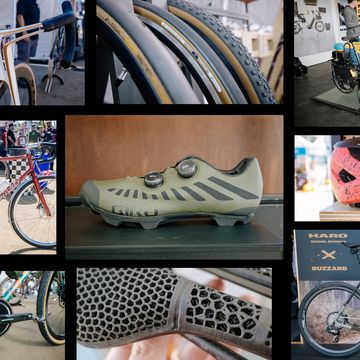

Alcohol, especially beer, is infused into many aspects of cycling. It’s in the bike shops, where customers still tip mechanics in six-packs. It’s been at industry trade shows like Interbike (R.I.P.) and Sea Otter, where bros in flat-brim caps drink openly while working their booths. It’s at cyclocross races, where #handupsarenotacrime; and gravel races, where aid stations offer whiskey shots. It’s been in the pages of this magazine, in stories like the ode I once wrote to the postride parking lot beer.

In many ways this relationship seems natural. Sports and alcohol are both outlets for leisure and socializing. But when I asked cyclists about whether the drinking within cycling was ever a problem, they cast the familiar scenes above in a new light. “The alley at the bike shop,” said one former professional road cyclist. “No one wants to address it publicly, but wow that’s a lot of alc.” A former bike brand employee told me about pitchers shared over work lunches and two DUIs received after work events, including Sea Otter. New York City bike messenger Dinah Gumns recalled a ’cross race where a female racer took every handup, shotgunned beers at the end, and couldn’t walk her bike back to her car, while everyone laughed.

When does drinking become problematic? Certainly when behaviors get dangerous, like binge drinking or drunk driving. But a booze-soaked bike scene may pose more insidious hazards, particularly to women. Gumns has seen men use the party culture within the messenger community to prey on women sexually or to excuse the predatory behavior of other men. Washington state-based bike mechanic Shannon Leigh told me that when she worked in shops, she felt pressure to get “stupid drunk” to be seen as one of the guys. Within the messenger community, says Gumns, there’s constant pressure for women to drink, in order to prove that they’re cool and fun. “If you’re not, you’re just another person’s nagging girlfriend.”

Bike events that promote too much bacchanalia can also feel exclusive to nondrinkers. By way of example, longtime rider and racer Elizabeth Allen, from Allentown, Pennsylvania, points to races with beer handups or shortcuts. “Why couldn’t it be a soda cutoff?” she asks. “Or if they offer alternatives, it’s really only offered to kids.” As a lifelong nondrinker, Allen has also been foisted into an unwanted role as the sober person in a crowd of sauced rides; seeing friends stumble around after cyclocross races causes her anxiety as she wonders whether it’s her responsibility to make sure they’re okay.

But maybe the biggest problem with the drinking culture in cycling is the most obvious one. Mitchell Williams, founder of the Major Taylor Cycling Club in Kansas City, tells me that his club members don’t generally drink after rides. “We’re looking at it from health reasons,” he says. “And drinking doesn’t seem to be that healthy.” Williams hits on the special cognitive dissonance in the fact that a health-minded group of people would habitually consume a product that hurts their health and performance. But odds are, most cyclists don’t know how even moderate drinking affects their bodies. And they might be surprised to find out.

To put it plainly, alcohol is bad for your health. Its negative impacts start at roughly a drink a day, and science that once seemed to support any health benefits of so-called “moderate drinking”—much of which was funded or promoted by alcohol companies—has since largely been debunked, including the myth that red wine is good for heart health. Every expert I spoke with for this story agreed that whatever minor benefits of light drinking remain, like lower blood sugar, are outweighed by the downsides, like increased cancer risk.

Alcohol is a Group 1 carcinogen, meaning that, like tobacco and asbestos, it’s been proven to cause cancer. (Red meat, by comparison, is a Group 2A carcinogen, meaning it “probably” causes cancer.) Decades of research on hundreds of thousands of women have established a dose-dependent response between even light drinking and breast cancer: For every 10 grams of alcohol a woman drinks each day on average (a beer has 14g of alcohol), her likelihood of developing breast cancer increases by about ten percent.

Light drinkers of any sex are also 30 percent more likely to get esophageal cancer, according to the National Cancer Institute, and that risk factor rises as consumption does. In fact, the NCI adds, drink a little more and you’ll expose yourself to other cancers: Moderate drinkers are 80 percent more likely than nondrinkers to get mouth and throat cancer, 40 percent more likely to get laryngeal cancer, and at least 20 percent more likely to get colorectal cancer. Prior to reporting this story, I already knew that alcohol’s link to breast cancer was considered rock solid. I was surprised to learn that the data on the head and neck cancers listed above is even stronger, as NCI program director David Berrigan, Ph.D., tells me.

Small amounts of drinking also increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, including stroke and heart failure. Just one drink a day has been linked to a 16 percent increase in the risk of developing atrial fibrillation, a heart rhythm disturbance that can eventually lead to either of the more serious conditions above. And drinking, even within the recommended guideline of two drinks a day for men and one for women, also literally shrinks the brain, though the cognitive effects are still unknown. (That daily consumption threshold, by the way, is not an average. You don’t get to drink an extra beer tomorrow because you skipped one today.)

This is all just if you stay within the recommended limits. A lot of drinkers don’t. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines “heavy drinking” as more than eight drinks a week for women and 15 for men, and estimates that one in six adults engages in binge drinking—that is, consuming four or more beverages in an occasion for women, or five or more for men. Heavy drinkers expose themselves to increased risk for all the conditions mentioned above—for example, they’re up to five times more likely than nondrinkers to get some head and neck cancers—plus injury and violence, liver disease, psychological disorders, memory and cognitive deficits, and alcohol use disorders. The American Cancer Society lists alcohol as the third-leading lifestyle risk factor for cancer, after cigarette smoking and excess body weight; in 2014, smoking caused 19 percent of all cancer cases and 29 percent of cancer deaths, and drinking caused 5.6 percent of cases and 4 percent of deaths.

Cyclists do have one major lifestyle factor on their side, of course: regular exercise. Just two and a half hours a week of physical activity can reduce the risk of all-cause mortality by about a third, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. But determining your individual risk of being diagnosed with a potentially deadly condition like cancer isn’t the same as simply doing the math on these population-level averages. This evidence, Berrigan says, “should inform you about what the healthy choices are, but there’s no guarantee that if you get a lot of exercise you won’t get cancer.”

Drinking within the recommended guidelines does mean that all the health risks are lower, which is why these limits exist. But the risks, particularly of cancer, are real, and surveys show that most Americans are still unaware of them. This has led the American Society of Clinical Oncology to make this unequivocal statement: “People who do not currently drink alcohol should not start for any reason.” The World Heart Federation adds: “The evidence is clear: Any level of alcohol consumption can lead to loss of healthy life.”

The gap in public knowledge about the health impact of moderate drinking is probably no accident. Some experts, like Mark Petticrew, Ph.D., a professor of public health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, says the alcohol industry has confused or misled the public for decades by funding or promoting research that seeks to either support the health benefits of drinking, or dispute its harms. It helps create and support organizations like ABMRF/The Foundation for Alcohol Research (formerly called the Medical Advisory Group). Between 1972 and 1993, the foundation and its precursor funded more than 500 studies on alcohol, including “one of the first papers suggesting that light drinkers had lower rates of heart disease than abstainers,” Mother Jones reported in 2018. Even the idea that beer may be a good postexercise recovery beverage was likely promoted by the alcohol industry, which has invited academics to present research on the subject at conferences, Petticrew tells me.

If the health impacts of drinking seem abstract to many fit and healthy-feeling cyclists, most athletes have some awareness that ethanol impairs multiple aspects of performance, especially recovery. Probably most widely known is alcohol’s dehydrating effect, which happens because booze inhibits the antidiuretic hormone that tells the body to hold on to fluid, causing too much to be released through urine. Alcohol also impairs the uptake of glycogen in your muscles, inhibiting the refueling effect of any postride carbs you eat and possibly affecting your performance for up to a couple of days, says sports dietitian Bob Seebohar, R.D.

Most people also know that drinking disrupts sleep, and Kevin Sprouse, director of medicine and sports science for EF Pro Cycling, enlightened me on the details. Specifically, alcohol shortens deep sleep cycles and disrupts REM sleep. Deep sleep is when the body releases human growth hormone, repairs tissues, and recovers physically; REM sleep is generally when cognitive recovery happens. When drinking sabotages these cycles, the result is compromised reaction time and mental focus and the ability to, say, navigate a pack or push through a tough workout the next day. EF riders wear Whoop fitness trackers, and performance staff have seen deviations in their sleep quality—as well as in metrics such as resting heart rate and heart rate variability—after as little as a single drink. Research supports their observations on sleep quality, too.

Finally, alcohol inhibits protein synthesis, the process of muscle repair that’s probably the most intuitive aspect of recovery to most people. If our legs don’t ache the day after a ride, we feel recovered. Knowing that alcohol inhibits this process, says Sprouse, “should probably hit home” to most riders.

Ironically, the fact that alcohol impairs performance may actually make cycling while drunk or hungover a casual display of athleticism in some circles. Mia Phillips describes an annual festival thrown by a mountain bike brand that hosts notoriously grueling rides, during which riders often carry beers. Once, she and a girlfriend brought beers and drank them warm 10 miles from the finish. “Everyone was, like, ‘You guys are so smart,’” she recalls, for having the foresight to pack in the mid-sufferfest indulgence; and in the moment, she thought, How badass are we. “Really, it was just stupid,” she says now, “because I could’ve ridden a whole lot faster if I didn’t have a six-pack in my pack.”

If alcohol is so counterproductive for cyclists, how did it become so ingrained in bike culture? The historical connection between bikes and beers is surprisingly thin. Early wheelmen and wheelwomen during the American bike boom of the 1890s didn’t appear to have had a widespread habit of drinking during or after rides. Some imbibed, but according to newspapers at the time, most seemed to agree with a New York cyclist who declared in an 1896 article that “beer goes to the knees and cuts off a man’s power of pedaling and of endurance.” A paper in Savannah, Georgia, reported that same year that “dealers in liquors and lager beer claim that the bicycle does them no good… The fact is the cyclist does not drink intoxicants.”

Historians I asked also scratched their heads at the idea that cyclists have a special affinity for alcohol. Sure, champagne is on the podium at bike races, but that happens in many sports, said one. It’s true that cyclists drank beer en route in the early decades of the Tour de France, but this was largely because it was safer to drink than water, as sanitation had yet to become standard, says cycling historian Les Woodland. Perhaps there’s a link, he acknowledges, in the fact that many of the world’s best riders and biggest races came from Belgium, where beer is integral to the culture. Still, Woodland thought it a weak link at best.

“Bikes and beers,” then, might be a more recent mashup. If so, it appears to be one promoted sparsely by bike brands themselves. I looked at 30 recent Instagram posts from each of 10 influential brands, including bike makers like Specialized, publications like Bicycling, and irreverent trendsetters like Ripton & Co jeans. Just one of the 300 photos displayed showed alcohol—a racer spraying champagne on the VeloNews account.

You’re more likely to find glowy lifestyle images juxtaposing bikes and beers on craft brewery accounts. New Belgium trumped all, with seven of its last 30 posts relating to cycling and beer. Oskar Blues and Deschutes Brewing also featured two posts each, like this photo of an Oskar Blues-branded jersey that read BIKES BEERS REPEAT. Other breweries, like Sierra Nevada, depicted beer alongside such outdoor activities as fishing and paddling. If the cycling industry seems ambivalent about associating itself with beer, the beer industry seems eager to appear cozy with cycling and outdoor sports in general.

There is a historical basis for this. In the mid-1950s, alcohol brands like Pelforth beer and St. Raphaël aperitif began to back teams in the Tour de France, and did so until France banned alcohol sponsorships in sports in 1991. In the U.S., money began flowing from alcohol into sports in 1970, when Philip Morris acquired Miller Brewing. Tobacco companies had long sponsored sports to lend their product a positive image, as the book Under the Influence: The Unauthorized Story of the Anheuser-Busch Dynasty tells it; the new Miller Brewing simply took a page from the tobacco marketing playbook and bought up almost every major sporting event from Monday Night Football to the World Series. As a war between Miller and market leader Anheuser-Busch kicked off, cash poured from both companies’ ad budgets into sports. Initially boxed out of the biggest events, Anheuser-Busch also turned to “alternative sports” like jogging, cycling, and softball, and by the mid-1980s it was sponsoring about 1,000 niche sporting events, such as the Bud Light Ironman Triathlon World Championships and the Michelob Night Riders cycling circuit race (as well as almost every MLB, NFL, NHL, and NBA team). The most famous cycling event, however, belonged to Coors, which from 1980 to 1988 sponsored the Coors Classic, and later the Coors Light team, which boasted stars like Davis Phinney and Ron Kiefel.

Sports have since become a cornerstone for alcohol marketing. A 2017 report by sponsorship monitor IEG estimated that U.S. alcohol companies spent 74 percent of their sponsorship dollars on sports—and not only mainstream spectator sports like football, but also participatory events like 5Ks, triathlons, and cycling races. The mass appeal of spectator sports is obvious, but participatory sports like running and cycling may be especially good at generating positive feelings about a product, says David Jernigan, Ph.D., a researcher on alcohol advertising at Boston University’s School of Public Health. “Anything that immerses you in a world that is at least in part created by the brand is going to work well,” he says. “You’re literally wearing the brand, on the T-shirt, on the number. It’s on the finish line, it shows up in every photo.” Alcohol advertisers are restricted by what they can show in ads—for example, they can’t picture an athlete drinking. But at an event, the participants themselves become the brand ambassadors.

Most importantly, associating with sports helps alcohol companies achieve the same goal the tobacco companies once had. “The real challenge here from an alcohol marketer’s perspective, is how do you make alcohol part of an active lifestyle when it has so many health problems associated with it?” Jernigan says. Federal law has strict requirements that prevent alcohol advertisers from making outright health claims about their products. “So the next best thing is to associate it with healthy people. Like athletes.”

In the glory days, Mark Taylor sometimes felt like the unofficial mayor of Emmaus, Pennsylvania. Taylor, as he was known by locals, was the lead mechanic in the local shop, which made him a social fixture of this bike-loving town of about 11,500, where a group ride left every day of the week. Bicycling magazine was headquartered down the street, and Taylor popped up occasionally in the pages of the magazine, too: He affected a stone face in his hip browline glasses for a cover; he smiled wholesomely for a Michelob Ultra ad saluting “America’s best bike shops.”

The shop was Taylor’s 500-square-foot fiefdom. His workstand sat behind a granite countertop, and he had the natural, laid-back demeanor of an old-school bartender, which made him easy company. People brought six-packs or 12-packs and hung out while he worked. They always offered him a beer, and if it was after 6 p.m., he almost always obliged. Sometimes, after he closed up, they’d head to the bar upstairs for a few more, which Taylor was happy to do, since he never had to buy. On Friday nights people gathered for happy hour at the shop and then migrated to the velodrome to drink beer and watch racing.

Looking back now, there was an awful lot of beer around. Taylor’s work schedule meant he could only ride a couple of days a week, but when he did, he liked to go long, and drinking was almost always involved. On a Saturday ride with friends, he and a small group might have “Milwaukee mimosas”—High Life mixed with orange juice—before the ride departed at 9 a.m., and at lunch he might have a beer or two as well. After the ride, Taylor could hang out for a few hours, drinking a couple of beers an hour. By his recollection, over the course of a day like that, he could consume between eight and 14 beers. In the fall, his weekly routine included a Thursday night cyclocross race in a Bicycling editor’s backyard, which featured a beer shortcut each lap, so he could be a six-pack deep even before the afterparty. It seemed like everything cycling was punctuated by alcohol, whether it was a 7 a.m. Tour de France viewing party or any given weeknight at the shop, as he kept up with whoever came in.

And he did keep up, because to him, the drinking was like the cycling. Taylor liked to be the first rider up the hill and the last man standing at the end of the night. Tapping out would be like walking a climb. Occasionally he would take a break from drinking—three months here, six months there—which assured him that he had it under control. He could stop whenever he wanted.

Research has repeatedly shown that athletes and active people drink more than nonathletes and less active people do. A 2021 study of some 38,000 participants, for example, found that very fit men and women, as measured by aerobic capacity, were 2.1 and 1.6 times, respectively, more likely to be heavy or moderate drinkers instead of light drinkers, compared to less-fit counterparts. One explanation for this is a phenomenon called the licensing effect, the idea that if you did something good or healthy, such as exercise, you now get to do something bad or indulgent, like have a beer, Kerem Shuval, Ph.D., one of the paper’s coauthors, tells me. Unfortunately, the desire to drink to reward oneself after working hard or performing well might also predict heavy drinking and negative consequences, according to a 2018 study of college athletes.

Another explanation for why athletes drink more may lie in a motivation dubbed “work hard play hard,” by University of Houston researcher J. Leigh Leasure, Ph.D., who is coauthoring a paper about the motivations that drive both exercise and drinking. In individuals, “work hard play hard” shows up as the tendency to “do everything to the max,” as she puts it: “They’re gonna exercise a lot; they’re gonna drink a lot.” Taylor’s approach to drinking as a competitive endurance event is a more extreme example of this, but many cyclists can probably relate with this mentality.

Cyclists also drink for one of the basic reasons all people drink: to be social. In his book Drunk: How We Sipped, Danced, and Stumbled Our Way to Civilization, Edward Slingerland, Ph.D., argues that alcohol facilitates human connection through its ability to downregulate the prefrontal cortex, our brain’s cognitive command center, which lowers our inhibitions and makes it harder to lie. “If I sit down and have beers with you, I put my prefrontal cortex on the table, I’m unarmed,” Slingerland tells me. He says that’s why drinking has long been a precursor to social activities that require mutual trust, like business deals, and that drinking can also happen after a cooperative effort, like a bike ride or race, to affirm and solidify the effort in the hopes of making it happen again.

Petticrew, however, adds a caveat to this narrative. “You can read a lot of research on how alcohol has helped people bond, but I don’t think you can look at it divorced from evidence that alcohol is also connected to fracturing relationships, to suicide, or to domestic violence,” he says. “We have a long history as a species of drinking. What we don’t have,” he continues, “is a long history of being encouraged to abuse alcohol by commercial forces.”

You can’t critically evaluate drinking within cycling without confronting an uncomfortable truth: that the alcohol companies most interested in associating with cycling today are not the Anheuser-Busches of the world, but beloved craft beer brands. Bike-themed beers like New Belgium’s Fat Tire and Deschutes’s Handup IPA have lined shelves of most beer aisles; a mountain biker dominates the home page of the Oskar Blues website, alongside the tagline “Adventure-Crushing Craft Beers.” The Colorado brewery even spun off a bike brand, cheekily called REEB Cycles, backwards for BEER.

Craft breweries are also the ones to sponsor most local rides and races. Of 165 cycling events I analyzed, half were sponsored by alcohol companies. Almost all were local craft beer brands, though the most prevalent national brands—New Belgium, Deschutes, Sierra Nevada, and the nonalcoholic Athletic Brewing —accounted for roughly a quarter of all sponsorships. When I asked Boston University’s David Jernigan why craft beer brands are so ubiquitous at local bike races, he laughed: “Because their marketing budgets are really small?” Craft brewers can’t compete with corporations on a national level, he says, so niche or local markets are their opportunity.

Of course, there is a big difference between Anheuser-Busch peddling Michelob Ultra, and a company like New Belgium, which was founded and run by people who genuinely love bikes. “At New Belgium, we view ourselves as part of the cycling community, not marketing to cyclists,” senior director of communications Adam Fetcher said in a statement to Bicycling. “Our participation is driven by a genuine love of the sport, and because bicycling can have such a positive effect on the world.”

Aaron Baker, senior marketing manager at Oskar Blues, echoed this idea, and added that the brewery’s motivation for sponsoring cycling events—including, in the past, Bicycling events—is more community-oriented than marketing-driven. “We’re not trying to, like, move the needle in terms of the perception of beer,” he says. “You can sort of reverse-engineer it and say, here are all the business reasons why it’s smart to be associated with cycling, but I think 95 percent of it is just authenticity and being true to who Oskar Blues is.” (While both New Belgium and Oskar Blues were founded by cyclists, New Belgium is now owned by a subsidiary of Kirin Holdings; earlier this year, Oskar Blues sold its brewing operations to the company that owns Monster Energy.)

Event promoters like Miguel Crawford, founder of Northern California’s popular Grasshopper Adventure Series, believe that craft beer brands support events out of a genuine interest in their local communities. Crawford, whose events are sponsored by Sierra Nevada, points to the company’s fundraising efforts to help victims of the deadly and destructive 2018 Camp Fire, which included its employees. He also dismisses the notion that he’s promoting problem drinking by providing a free beer with lunch, when riders can bring their own coolers. “If riders have a tendency to drink too much,” he says, “that's what they’re going to do anyway.”

Promoters and craft beer spokespeople say they’re simply supporting moderate, responsible drinking at bike events. But the concept of “responsible drinking” is also one that the alcohol industry has historically muddled to suit its own aims, Mark Petticrew tells me. One tactic, he says, is to use terms like “responsible” vs. “harmful,” but then fail to define them or use confusing definitions, because no one wants to believe they’re a heavy drinker. Pinning responsibility for problem drinking onto a hypothetical subset of problematic individuals allows the industry to avoid the fact that alcohol is addictive, and that a large portion of drinkers don’t stay within recommended limits.

The alcohol industry knows that many of us are overserved, because a high proportion of its profit has historically come from people who drink more than they should. If the top 10 percent of drinkers—who averaged a staggering 74 drinks a week—were to curb their consumption level to that of the next lower decile, alcohol sales would fall by 60 percent, according to economist Philip J. Cook's analysis of 2001-2002 data in his book, Paying the Tab: The Costs and Benefits of Alcohol Control. The industry, Petticrew says, “needs harmful drinking. It depends on it.”

My common sense finds it difficult to imagine executives at companies like New Belgium or Oskar Blues devising plans to convert fellow cyclists into problem drinkers. And the industry in general argues that its marketing serves only to engender brand loyalty among people who already drink. But research shows that alcohol marketing can influence our actual beliefs and drinking habits. Studies show that sports sponsorships are associated with higher levels of drinking among athletes, that they may generate positive attitudes toward drinking among spectators, and that they may also increase the odds that youth who are exposed will start drinking earlier and in greater quantities. Other studies suggest that social media marketing—such as the Instagram posts I found juxtaposing beer and cycling on craft beer accounts—can not only increase the desire to drink among viewers, but promote their perception that drinking is positive and normal, thanks to the reinforcing effect of comments and “likes.” Finally, the craft beer industry may be helping to shape a drinking culture by simply ensuring that its product is always around and always affordable—or in the case of cycling events, free. That’s because, according to Petticrew, “the availability of alcohol is a strong influence on consumption.”

Regardless of the motivation behind it, the association with bikes so lovingly promoted by craft beer companies may have the same result as the sports marketing tactics pioneered by corporations like Anheuser-Busch decades ago. It gets us to associate a healthy activity with a product that jeopardizes our health. And maybe it’s worked. “It is odd,” muses Alec Linton, a Denver-based mountain biker, “that cracking some IPA or craft sour after a ride is looked at differently than a Budweiser.”

In 2014, I moved to Emmaus to take a job at Bicycling. The week I started, I dropped my bike off for a tuneup at the local shop. The mechanic wore hip glasses and had a thick mop of dark curls, and when I told him my name, he said, “You’re here from Colorado. We heard you were coming.” It was the kind of small-town welcome a homesick transplant sorely needed, and I’ve been endeared to Mark Taylor since.

When we got back in touch recently, years after I moved back to Colorado, Taylor told me about the drinking problem he now acknowledges he had, the way it felt entangled with the sport and the community he loved. He told me about the night that should have scared him straight—when he crashed while riding his bike home from a bar and ended up in a trauma unit—and the night that actually did.

On a warm, beautiful spring evening, Taylor pedaled to a cycling fundraiser at a local brewery about 10 miles away. He stayed until midnight, drinking what would ultimately be about a dozen beers by his estimate, then made an utterly uneventful ride home. Everything was fine until he got to his front door. There, he fumbled for five minutes to get his key in the lock. When he finally succeeded, his wife Trisha was standing on the other side. She’d been there the whole time.

Taylor saw the look on her face and knew there was no hiding it. He was completely exposed. He’d ridden his bike 10 miles on open roads when he couldn’t even operate the key to his house. Ashamed of how much he’d endangered himself and others, he slept on the couch in the basement that night. The next morning, he told Trish he was done drinking. Not a break this time. Permanently.

That was five and a half years ago, and Taylor hasn’t had a drink since. That dogged, no-DNF mentality he once took to drinking and cycling now marks his sobriety. “It’s like the biggest endurance sport,” he tells me. “It’s a lifelong challenge that I’m not gonna lose.”

Mia Phillips, of Crested Butte, is now sober too. During the pandemic, her drinking got significantly worse. She was getting sick on the bike and saying hurtful things to friends. Finally, a year ago, she started going to Alcoholics Anonymous. Since then, the woman who moved to paradise to ride more has barely touched her mountain bike—it just feels too connected to her identity as a drinker. But she hopes that will change over time. “The bike has always been an extension of me,” she says. “It gave me such joy.”

I was happy to hear how well Taylor was doing, but my conversations with him, Phillips, and other cyclists, also left me unsettled. Over the years, I’d wondered about my own drinking. It had calmed down since my hard-partying 20s, but I still regularly blew through my one-drink daily guideline enjoying craft beer after rides, and I can mindlessly achieve the CDC’s four-drink definition of a “binge” just sipping IPAs around a campfire. I was halfheartedly trying to cut back over the past year as I learned more about the health effects of drinking, but between social events and the general postwork unwind, it was too easy to slide back into my near-daily pattern of reaching for a beer after I shut my laptop—and after that first beer, it was even easier to crack the second. My drinking had always felt like something I would have to deal with at some point, like an expensive car repair I was putting off. Now I wondered if that time was here.

I could see myself forgoing the happy-hour marg and the glass of wine I’d savor while I cooked. But the drink I really didn’t want to give up was my postride beer. Over the years I’d come to crave the way the warm buzz soothed my tired, happy body. I loved the ritual of gathering around a tailgate with friends, wrung out and salty-skinned, as we made our cold cans kiss under a dusky sky. The joy of these moments felt real, not like something manufactured or marketed to me.

But how much of that was the beer, and how much was the ride? One afternoon, while pondering that question, I suddenly recalled a detail about my cycling life that had somehow eluded me all these years. Now it surfaced like a once-repressed memory: When I first learned how to mountain bike, I had actually been taking a yearlong break from drinking. None of those early rides had been followed by postride beers, I realized—and I fell in love with the sport anyway. Maybe there could be a future when the two were less in lockstep.

As of this writing, I’ve been on a three-month break—of sorts—from booze. Most days, I don’t drink. But rather than teetotaling, I enjoy a drink on special occasions. It’s an intentional approach to long-term moderation that some people call “mindful drinking.” I’m not alone in taking a harder look at my habits. Over the past year, more friends have pulled NA beers out of the cooler after rides, and Athletic Brewing tells me it will likely finish the year as a top-20 U.S. craft brewery by volume sold. As Americans in general reevaluate their relationship to alcohol, maybe it’s a good time for cyclists to reexamine ours too. The alcohol industry has long needed to be associated with the sports we love. Does our sport still need to be associated with alcohol?

“The constant cross-promotion of alcohol and cycling,” Taylor says, “is so deep, it’s just crazy.”

Taylor admits that there has been one painful aspect of sobriety, which is that he’s no longer close with many of his old friends. “I stopped drinking, and the phone stopped ringing,” he says. He’d heard that this might happen, but he still felt some level of disbelief seeing it actually play out. “It hurt my feelings, you know? I thought a lot of the friendships were deeper than they were.”

But even as he predicted that some of his relationships might change, he also knew he’d always have cycling. And he does. He rides less now, and most often with his kids, but he tells me the quality of the time is greater than it’s ever been. He’s no longer chasing fitness, just pure enjoyment. In a way he too has returned to an earlier version of himself as a cyclist, when he was a daredevil kid building dubious BMX jumps and sailing off them sans helmet; or a fresh high school grad on his first road bike, pedaling as far as daylight would let him, no map, no plan, and what felt like no limits. It now seems silly to him, that he once believed being altered could make anything about the experience better. “Bikes are fucking perfect,” he says. “They don’t need enhancement.”

Think you might need help? Start here → The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has a helpful alcohol treatment navigator, which explains the hallmarks of a substance use disorder, what kinds of treatment you may need, and links for reputable treatment providers.

START HERE