What Qatar Built for the Most Expensive World Cup Ever

The 2022 football World Cup gets underway Sunday, with hosts Qatar taking on Ecuador. In the 12 years since the tiny gas-rich country was awarded rights to the event, it has spent $300 billion preparing for kickoff. Doha has been transformed, with the capital now dotted with new stadiums and hotels built to accommodate more than a million fans over the next month.

The tournament is the first World Cup to be held in the Middle East, in many ways the culmination of the wider region’s grand ambitions in the world of sports. Qatar and its wealthy neighbors have plowed billions of dollars into major European football clubs, the region will host four Formula 1 races next year, and the Saudi-backed LIV tour aims to dominate professional golf.

A tournament of many firsts, Qatar 2022 has been accompanied by controversy from the beginning. There have been concerns over Qatar’s record on policies that limit rights of women and LGBTQ people and its treatment of migrant laborers. The government’s claim of hosting a carbon-neutral World Cup has been discredited. On top of the disruption of shifting away from the traditional summer time slot, there was a last-minute change to the schedule.

All told, the tournament is still expected to deliver record revenue for organizers FIFA and top the roughly $5.4 billion that the 2018 World Cup in Russia generated for football’s governing body. About 3.6 billion watched the last World Cup and billions are set to tune in to this edition.

Green Fields in the Desert

The quadrennial tournament arrives in the Middle East for the first time in its 92-year history, making it the biggest sporting event ever to be held in the region. It’s also the first global spectacle open to spectators since Covid-19 restrictions shut out fans for the Tokyo Summer Olympics and the winter games in Beijing.

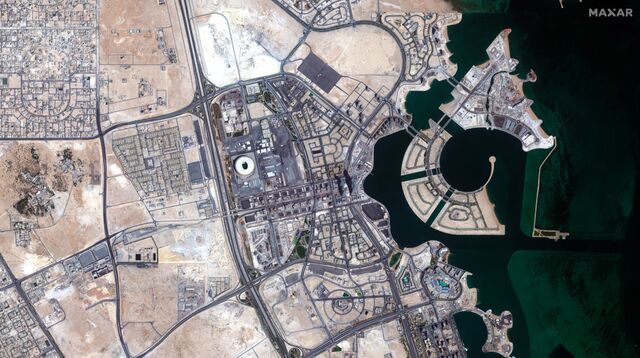

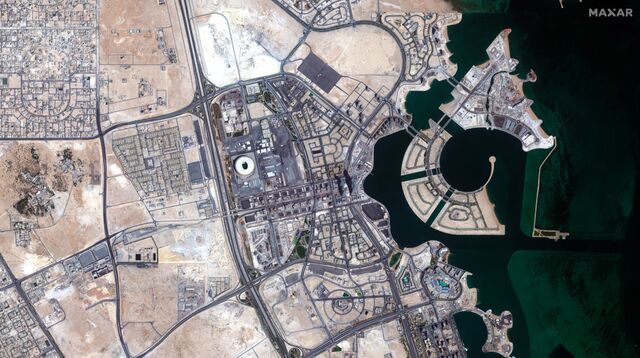

And unlike previous World Cups, where venues typically stretched across multiple cities, all games will be played within 31 miles of Doha’s main Corniche. That means the capital will swell by over a million fans, roughly a third of Qatar’s entire population, for the month-long tournament.

In another departure from tradition, it’s the first time FIFA is holding the event in November and December instead of the mid-year months to avoid Qatar’s scorching summer. That has upset European league schedules, drawing consternation from players worried about injury and exhaustion.

For the Fans

Close to 3 million tickets — almost all the available seats — had been sold by mid-October. Alongside Qatar residents, people from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates were among the top buyers, FIFA has said. Fans from the US, Mexico, Britain, France, Argentina, Brazil and Germany are also set to arrive in Doha, while Covid restrictions are keeping visitors from China away.

Qatar’s small size has posed a challenge for organizers, who have turned to non-traditional accommodation including cruise ships, desert camps and serviced apartments to house fans. The plan is for 130,000 rooms to be available, but many hotels haven’t been completed in time for kickoff. Apartments in far-flung neighborhoods raise questions about how much fans will enjoy the experience.

Extra Shuttle Flights

Same-day return flights to nearby cities for World Cup visitors

Infrastructure Projects

Qatar has also turned to its neighbors for help. Close to 100 daily return flights between Doha and other major Middle Eastern cities will allow visitors to stay outside the tiny Gulf state. Dubai has especially seen a surge in demand for hotel rooms. Just a 55-minute hop from Qatar, the tourist-friendly emirate — with its more lenient dress codes and party culture — is expected to benefit the most.

Organizers say the compact size is a feature, not a failing. The close proximity of stadiums and the transport links will allow fans to attend multiple games on a single day, they say. Most stadiums will be linked by public transit, including a new metro system and a fleet of electric buses. While that will help decrease the tournament’s environmental impact, it won’t be carbon-neutral.

Metro Network

Connecting the stadiums to Downtown Doha

Liquid Funds

Qatar’s exorbitant wealth is mainly drawn from exports of liquefied natural gas, a super-chilled version of the fuel that the country ships to mostly Asian buyers under long-term contracts. The country shares one of the world’s largest natural gas fields with Iran, its neighbor across the Persian Gulf.

The fossil fuel has made the country one of the world’s richest on a per-capita basis. Its native population numbers only about 350,000 Qataris — the official number is never published — with the bulk of the residents made up of expats, mainly on work visas. Thanks to robust oil prices — the peg for most of Qatar’s contracts — the country is enjoying a bumper year and expected to generate a surplus worth 13% of gross domestic product, according to S&P Global Ratings.

With demand for LNG surging alongside Europe’s energy crisis, the country has embarked on an almost $50 billion project to expand capacity by more than 60% before the end of the decade. Capital Economics predicts that the expansion will boost its GDP by 25% by the end of 2027.

Largest Projects Ahead of the World Cup

Qatar says event deadline sped their delivery

A brand new metro system, a modern shipping port, an expansion of its main airport and the construction of a planned city north of Doha have transformed the country. Authorities say that much of the construction was already under consideration, but that the World Cup pushed up the timeline.

Power Play

Critics have accused Qatar of “sportswashing” to gloss over its poor treatment of migrant workers, people that identify as LGBTQ and other minorities. While Qatari officials are hoping that the event garners global goodwill among football fans, geopolitical considerations may be more important.

Tucked between Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Iran, Qatar sits in a tumultuous region. Relations in the region are delicate and often tense. In 2017, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt and Bahrain cut off diplomatic, trade and travel ties with Qatar, accusing the country of funding terrorists — a charge Qatar denies — and being too close to Iran. The move was seen as a threat to Qatar’s sovereignty, and US diplomats played a critical role in preventing the situation from deteriorating. Relations were only restored in early 2021, also with the help of US mediation.

The World Cup offers Qatar a chance to flex on the global stage, and that name recognition may be crucial in warding off a similar threat down the road, according to some analysts.

Organizing such an event despite its small size also gives Qatar international credibility, says Fahad Al-Marri, co-head of the Small States Research Program at Georgetown University in Qatar.

Hangover Risk

Qatari officials hope that the infrastructure developed as part of its preparations for the World Cup will assist in boosting the country’s non-energy economy, even if it doesn’t have a firm plan for what to do with all those shiny new stadiums.

While LNG may be a hot commodity now, Europe eventually aims to end its reliance on fossil fuels. Media depictions of Qatar as sleek and modern could help with that, drawing tourists and businesses. The development of ports and roads could also boost manufacturing.

Most economists expect non-energy business activity to slow in the aftermath of the tournament as apartment buildings and hotels empty of World Cup visitors. Thousands more hotel rooms, some planned for the World Cup but not completed in time, are expected to hit the market in 2023. On top of that are thousands more residential units.

The government has said it expects low-income workers to leave the country as construction projects dry up, but it’s not clear how many white-collar workers who were involved in preparations for the football tournament will depart as well.

Qatar’s population grew by close to 14% in the year ending Oct. 31, to a record 3 million people. And the country faces the risk of an empty feeling once the fans go home. The government hopes that an end to the World Cup frenzy will herald the dawn of a more viable knowledge and service-sector economy, but the path between a major sporting event and the next phase of economic growth remains unclear.

That makes the post-tournament transition as important as the buildup if the investment is going to ultimately pay off.