Well, that didn’t take long.

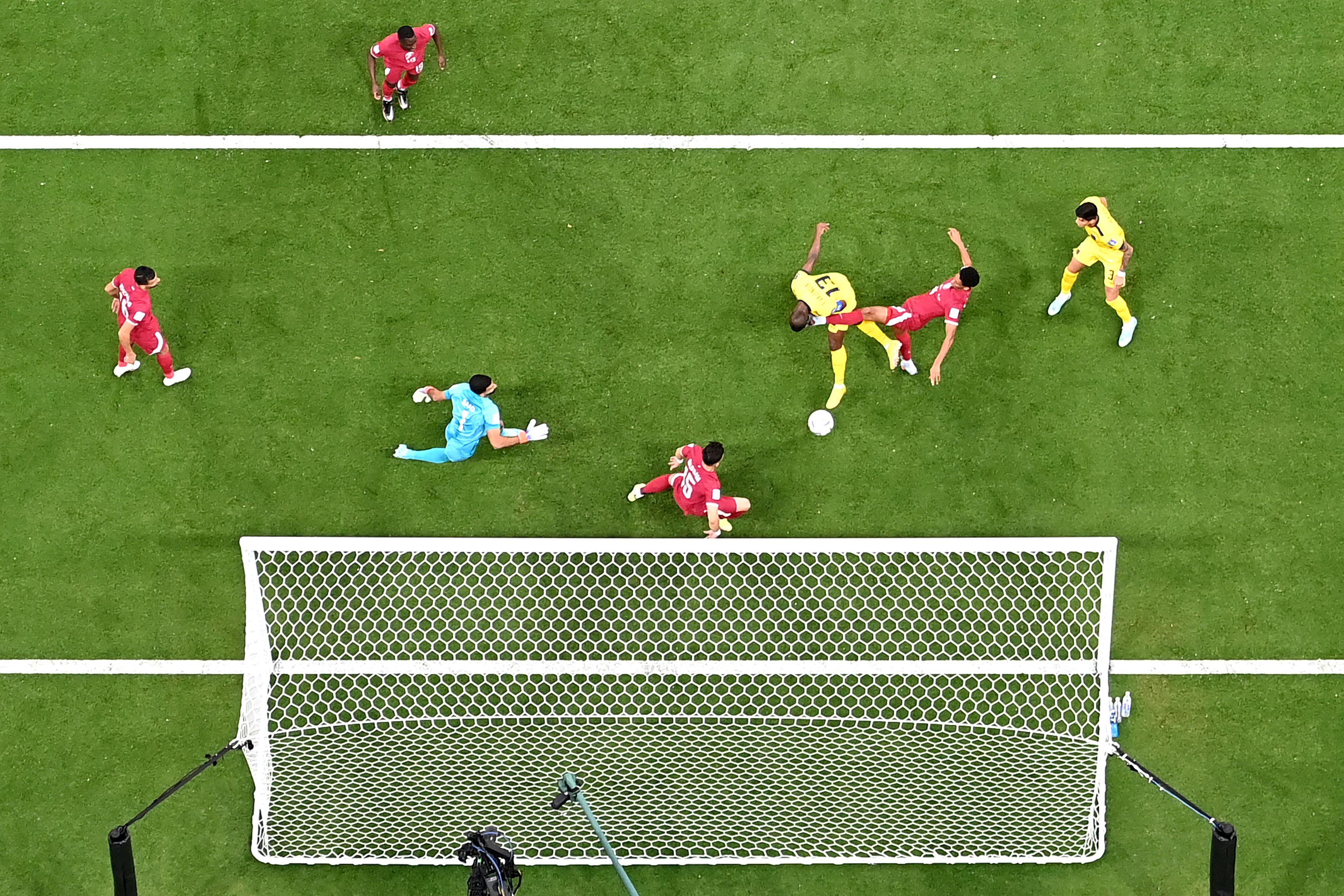

Just 158 seconds into Sunday’s opening match of the World Cup in Qatar, referee Daniele Orsato relied on soccer’s new semiautomated offside technology to nullify what otherwise would have been the fastest World Cup goal ever. That Enner Valencia’s disallowed goal for Ecuador was against the tournament’s Qatari hosts only added to the enormity of SAOT’s intervention, leading to plenty of debate at home, in the stadium, and online.

The close offside call, clear only to SAOT, was technically correct. But whether it’s correct in some bigger meaning-of-life way depends on where you come down on longstanding debates over the efforts of soccer’s governing body, FIFA, to deploy high-tech solutions to assist officials.

Soccer has been relatively slow compared with some other sports to incorporate technology into officiating. Part of the universal appeal of the jogo bonito, the beautiful game, is its fluidity, its fatalism and the simplicity of its accessories. When I played soccer as a kid, the kit was limited: Our uniforms were blue T-shirts hand-lettered in black magic marker. We were required to wear shin guards and athletic cups, but few of us had cleats. The children of overprotective parents wore knee pads. We weren’t kicking around grapefruits or socks stuffed with newspaper, but our soccer equipment was an afterthought compared with the expensive gear of (American) football or baseball. The referee’s equipment consisted of a watch to keep time, a small notepad, a pencil and yellow and red cards to book a player for a serious enough infraction, and a whistle to start or stop play when the ref spied a foul or if the ball crossed entirely beyond the goal line or out of the field of play. The two linesmen (as they were), usually assistant coaches on the competing teams, had small flags to raise to signal the referee if the ball went out-of-bounds or to suggest an always subtle and often controversial offside call.

Soccer at higher levels was largely consistent with this simplicity, and the game (even not at its best) consequently has a continuous ebb and flow entirely unlike sports punctuated with innings, downs, time-outs, or too much scoring. But to channel this freedom and fluency, the game also has its rules—formally known as “the laws,” which appropriately awed me as a schoolboy.

But times change, and so does technology.

And so do the stakes. At a certain point, too much was at stake financially for players and clubs, as well as their global cartel, to simply rely on three pairs of human eyes, especially when global audiences at home could second-guess them with the aid of slow-motion, close-up, replays.

Nothing demonstrated the cost of human officiating’s fallibility more than Diego Armando Maradona’s infamous “Hand of God” goal in the 1986 World Cup quarter-final match between Argentina and England. My father and his friend Larry were among the more than 100,000 fans in Mexico City’s Estadio Azteca—and many millions worldwide—who all saw what the referee did not: Maradona propelling the ball past the rival goalkeeper with his clenched fist.

That same year, American football first experimented with instant replay technology. Despite the controversy and available technology, FIFA rejected the opportunity at the 1990 World Cup to implement instant replay, arguing that it would interrupt the flow of the game. (Many years later Maradona would admit that the deployment of such technology would have cuffed the Hand of God.) Despite various experiments locally, FIFA continued to resist a full-blown video-assisted refereeing system until the 2018 Men’s World Cup held in Russia, though four years earlier in Brazil it had permitted the goal-line technology that immediately advises the on-field referee if the ball has crossed the goal line. VAR in Russia and across a number of domestically leagues has been deemed a technical success, though the argument still rages about at what cost to the game’s fluidity and spontaneity.

On Sunday, neither the full-speed nor slow-motion replay of Ecuador’s early goal against Qatar seemed to show the infraction. But the digital reconstruction provided by the SAOT—complete with cheesy, abstract graphics derived from the system’s 12 tracking overhead cameras in the stadium, the 29 data points (also known as body parts) on each player, and a microchip in the ball—did freeze the lower part of an Ecuadorian leg in the offside position. Only then did the referee, in collaboration with this array of technology, make his call, leading the Fox commentators on U.S. television to speak reverently about how “scientific” the system is.

To understand this interaction among referee, cameras, sensors, micro-chipped ball, and who-knows-what-else as a collaboration is more than metaphorical. The late French philosopher Bruno Latour helped germinate actor-network theory, which helps explain how collaboration among people, objects, and technological devices extends scientific and technological domains while simultaneously providing them with social meaning. Latour redefines what we normally understand as human actors and objects instead as “actants” allied together in a network. The network associated with refereeing a soccer game when I was kid was largely limited to what the ref could carry on their person and those two additional human assistants.

Now, the network incorporates an arsenal of technological marvels in league with the human officials. But where are the fans in the stadium or those at home in this network?

For the authors of the book Bad Call: Technology’s Attack on Referees and Umpires and How to Fix It, a congruency between experiences within the network is crucial: “[J]udging what happens on a sports field is a matter not of ever-increasing accuracy but of reconciling what television viewers see and what match officials see—it is a matter of justice.” They suggest, quite rightly, that the precision of tech such as VAR and SAOT transforms the field of play from a real to a virtual pitch, from one with deformed, air-filled bladders in a synthetic leather casing spinning and bouncing in grass and mud and lines of chalk, to one with points and pixels on some imaginary grid with laser-precision.

The game is played and witnessed in the former space, but refereed in the latter, and all done to enforce “the law.”

But law is its own technology. The American political scientist Langdon Winner suggests that we identify and not just analogize legislation with technology. Law and technology are one and the same—they are two things that people make collectively to live with and through, and they direct and constrain our ability to do what we perceive as good and right in the world. If we accept the idea that legislation requires certain democratic norms and institutions to make justly, then we must consider that we should have some democratic norms and institutions in making technologies.

In the case of soccer, that consideration only punctuates the question of who is the technology actually for—club owners and national federations, players, fans, the big media companies underwriting the spectacle, or FIFA itself? Who has had a voice in the choice of these technologies? We might further ask whether such technologies then affect how the law might evolve: Do we need to revisit the laws of soccer, for example, the offside rule, to recognize the difference between playing on a real pitch and officiating through a virtual network on a digital pitch? Given how poorly FIFA has performed in selecting Qatar for this World Cup and in overseeing how the host nation has done in everything from supporting the human rights of its construction workers and its citizens to providing ordinary fans with beer, I have very little confidence FIFA’s making a technological choice in the best interests of the fans or the game. Perhaps, for instance, FIFA is trying to draw on the respectability and integrity of the “scientific” in order to bolster its own standing.

So as you’re rooting for your favorite players and teams of this World Cup, and as the passionate flow of the play is interrupted by the referee’s consulting the VAR, rather than cursing the delay or getting another helping of chips and guac, you might ask yourself: Who is the technology really for? Who had a voice in deploying the technology? And is justice always served by technical precision?

Better yet, if life is a game, ask these questions when you’re not watching the World Cup, and just enjoy o jogo bonito.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.