Back in my salad days, I carried myself with swagger. The dashing raconteur—that’s the role I liked to play. But today, I never turn on the charm the way I used to years ago. These days, I make a conscious effort to mellow my manner in mixed company.

I’m talking about man issues, which for decades I had confused with girl problems. That confusion sent me on a quest leading to some of the most desired and objectified women in the world. If I’d read different books, watched different movies, and looked up to different role models as a kid, I might’ve figured things out earlier. Instead, here I am with my hair turning gray and I’m still revising my understanding of the man I want to be. My self-diagnosed girl problems began around puberty: I was that late bloomer with zits all over my face and a body like a heap of knees and elbows. Plus I rarely asked questions, and when I did, I had a habit of interrupting the answers.

I addressed my girl problems by cultivating, as the kids are saying, some of that main-character energy. I emulated popular kids who made clever remarks and told impressive stories. I read articles about my abdominal muscles and chugged a steady regimen of blended protein cocktails. I did all this with the vague goals of gazing into someone’s eyes, riding horses with them, and maybe fighting a duel for their honor—though I would’ve settled for just touching. My clumsy efforts did not lead me to meaningful relationships, which require skills I couldn’t even name back then. But they did help me get scouted to become a model.

Modeling seemed like a dream job. The pay was sometimes good, and I flew coach all over the world. Bouncers treated me like a celebrity. And then there was the table—do you know about the table? Plenty of men will buy overpriced vodka in exchange for proximity to pretty women, so certain nightclubs keep a table where female models eat and drink for free. The female models invite the male models to come along and serve as buffers against these men, and voilà! Enter main character.

That’s where I was, surrounded by tall women with nice teeth and cute accents, when the fissures began to appear in my facade. I’d be laying the charm on one of my coworkers, telling her my elaborate jokes and impressive stories, and she’d roll her eyes and express to me that she was never, ever going to make out with me, so I might as well relax and enjoy myself, and maybe we could be friends.

These women knew all the shticks. They saw right through the bluster I used to mask my insecurities. By calling bullshit at the models’ table, they planted the seeds of an eventual transformation. But I still had a long way to go. I accepted their offers of friendship, figuring that models might make good wingmen. But my women friends could be real buzzkills sometimes. For example, say you’re at a nightclub in Shanghai or Miami, grooving along to some brain-melting house music, and you shout to your friend Kimberly, “What’s up with your new roommate? She seems cool!”

And Kimberly shouts back, “She’s 14 years old, she just got here from Siberia, and she doesn’t speak a word of English!” Or: “She induces herself to vomit using a feather dipped in olive oil so that she doesn’t get calluses on her knuckles!”

Kimberly is not her real name, but these stories are true. I knew guys who went to the gym twice a day, and guys who subsisted on broccoli and tofu, but no guys who carried a feather, no guys who should’ve been in the eighth grade. The longer I worked in modeling, the more I saw that the demands on women were far more harmful.

And then something else happened: I experienced sexual harassment. It wasn’t as bad as some of the stuff you’ve heard about. What I’m talking about is unwelcome physical contact and lewd comments in workplace environments. I’m talking about being treated like a piece of meat with no opinion and no power. When I told my female friends about it, they’d reply, “Welcome to every day of my existence.” Deflecting unwanted male attention was an unavoidable part of their lives, they said, and most other women’s lives, too. And they had to live with the danger that a man might respond to rejection with aggression.

Learning how often my friends encountered harassment led me to think more deeply about women’s experience of male behavior than I ever had before. I asked my friends more questions, and I stopped interrupting the answers. Instead of filling every silence in social situations, I allowed myself to pipe down and observe, and I noticed how often men treated women like objects or audiences. I began to read books by women authors, such as Rachel Cusk, Rebecca Solnit, and bell hooks, who revealed to me the egocentricity of behaviors I’d thought were cool. I’d always aspired to become some slick, assertive hybrid of Dean Moriarty and James Bond. Now I was discovering that acting like the main character was a dismal approach to forming genuine human connections. It was a shock to the system. I’d thought I was ascending to the apex of manliness, only to learn that I was mimicking the manners of the bonobo. Why the hell had I drunk all those disgusting protein cocktails?

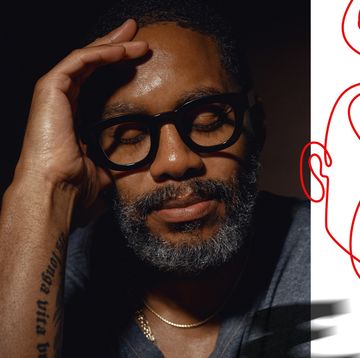

My modest modeling career peaked in 2012, the year I was painted life-size on all the yellow cabs in Singapore (above), grinning and paying with Mastercard. Modeling never made me rich or famous, but I got something more valuable from my experiences: I saw up close how the global economic spectacle machine treats women as objects. And I realized that I’d been doing the same.

These days, I have a new modest career writing crime novels. In my stories, I try to poke holes in the traditional formulas, in which badass men conceal their feelings behind gruff exteriors and hypersexualized women serve as their victims, prizes, pillows, and mirrors. In my personal life, chiseling my chest muscles has fallen off my list of priorities. Instead, I’ve been working on decommissioning my ego. This project involves such practices as meditation, journaling, and making a mindful effort to say words I rarely heard from men when I was a boy, such as “I don’t know,” “I’m sorry,” and “How can I help?”

I’m happy to report that this approach works much better than my old one. It turns out that being empathetic is much more lovable than being impressive. The big empty lie about the cool-guy masks men wear is that they give us power. On the contrary, nothing is more liberating than letting go of the drive to dominate. When I stopped trying so hard to make women like me, I uncorked my capacity for true intimacy. I met a soulful and hilarious woman, and together we learned to love each other in all our unvarnished, marvelous humanness. Our shared enthusiasm for adventure led us to an open relationship. Nonmonogamy sometimes resembles both having and eating our cake; at other times, it requires a black belt in selflessness. I hardly feel like the main character when she’s brimming with excitement about someone else. But I can dispel my insecurities with six simple words: “It’s not always about you, dude.”

This article appeared in the SEPTEMBER 2022 issue of Esquire

subscribe

Most of my model friends have retired or, in Kimberly’s words, have been “shuffled off to socks and underwear.” She’s 33, and recently her body appeared in a major fragrance campaign, attached to the head of a celebrity who’s 41. There’s less work available for men, but we’re welcome on camera much longer. I still book a handful of jobs each year. It seems that I’m graying into Ethnically Ambiguous Millennial Dad. (That’s me now, in the artwork up above.) My typical modeling job entails playing house with a couple of model children and a model wife, who might be, say, 25.

Nowadays I resist the impulse in such situations to regale the room or nonchalantly pop into a handstand. Such are my man issues: I’m unlearning behaviors that I once assiduously studied. It’s not always easy. Sometimes, just deciding where to allow my gaze to wander incites a shouting match inside my head. But of course, constantly performing my maleness wasn’t easy, either. And now I have twice as many friends.