The American Faith I Was Raised In

Growing up in the Bible Belt, I was taught that Church and state should never have been separate.

I was raised in a very specific American faith. This American faith is not patriotism, not a love of this country—though it contains some of that. Nor is it Christianity—though it contains some of that too. It is the belief that Church and state should never have been separate in American life, despite all the un-Christian aspects of the Founders, such as their distinctly secular philosophies and their explicit, repeated commitment to that separation. Today’s Christian nationalists have fought for this particular faith over decades.

And that fight paid off when, at the end of June, the Supreme Court released its long-awaited decision in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District. Joseph Kennedy, a high-school coach, had sued the Bremerton School District for firing him for praying on the field at the conclusion of football games. Prayer in schools, a practice that had been considered illegal since Engel v. Vitale was decided in 1962, was instantly legal again. Conservative-Christian groups did nothing to hide their excitement. The American Center for Law and Justice, a legal-advocacy organization founded by Pat Robertson and run for decades by one of Donald Trump’s personal attorneys, Jay Sekulow, issued a statement that read, “For a long time, countless progressive elites and liberals have emphasized that a wall of separation has been established between public life and religion. In reality, of course, there has never been a wall of separation.”

There has never been a wall of separation. My younger self would have celebrated.

I grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the buckle of the Bible Belt. I imagine that my parents moved our family there because, among many reasons, Tulsa bore no resemblance to New York, the city where I was born. Tulsa’s brown, flat, predictable landscape; its many churches and Christian schools; its political leaders whose speeches sound like sermons and preachers whose sermons sound like political speeches—these features were a welcome relief to parents, not just mine, who wanted to raise “God-fearing kids” in a world that seemed ever bent on secularizing.

The Christian school I attended from sixth to 12th grade, most years as one of the only Black students, branded itself “classical.” By classical, the school’s leaders meant that the school’s traditions were not of this age, and not of this world. “To be in this world, but not of it” is a synthesis of biblical texts formed to command followers of Christ, then and now, to realize that being in this world, involved in its cultures, is not a choice. But to become of it—for our behaviors, political leanings, and the like to resemble those one would find in the “secular world”—is a sinful step too far. So the school tried to carve its own path.

Every Christian school I had attended before this one taught mathematics, English, history, a foreign language, and, if it had sufficient budget, physical education. Those institutions also shoehorned a Bible class into the course schedule. That’s what made it a “Christian education.” But this school was of the view that education wouldn’t be Christian without a Christian worldview finding its way into every single class. In science, we learned that God created the world some 10,000 years ago. Biology was one part biology and two parts disputing evolutionary biology.

What haunts me most today, what I am still unlearning, is the school’s accounting of this country’s history. My belief now—which was my hunch then—is that the purpose of the history education I received was to convince me that God has a plan and that that plan has always included America as a shining city on a hill. Although the public fights today about whether this country’s founding was in 1619, when enslaved people arrived on these shores, or in 1776, when enslavers who moonlighted as politicians declared independence from the Crown, our school had a third view: America had been in God’s mind from before the dawn of civilization.

History class was conducted in celebration of the Founders and their Christianity. We watched videos and read pamphlets and materials by David Barton, a noted Christian nationalist whose organization, WallBuilders, promotes the belief that the United States was founded as a Christian nation. Fringe figure though he may seem, Barton’s work has been praised by major political leaders on the right, including Newt Gingrich and Mike Huckabee. And if my tenth-grade history class was one 32-week, two-semester-long argument for why God was the true founder of America, my 11th-grade history class was a training ground for defending this view.

The book we relied on most was How Should We Then Live? by Francis A. Schaeffer. This 1976 book argued that Western thought had at one point—long ago—been rooted in Christianity and that with the decline of Christianity’s influence on the West, the vitality of Western life had been destroyed. Schaeffer examined the environmental movement, race, the emergence of hippies, the Enlightenment, evolutionary theories, art by Salvador Dalí, music by John Cage, the Renaissance, and more, only to conclude that philosophy and science were in catastrophic decline.

Schaeffer’s central thesis was simple: “When we base society on the Bible, on the infinite-personal God who is there and has spoken, this provides an absolute by which we can conduct our lives and by which we can judge society.” This fusion of a Western-oriented Jesus and the state was the only bulwark against the decline.

The West—and, more narrowly, the America that Schaeffer wanted to preserve—wasn’t just a more religious one, explicitly. It was, implicitly, a whiter one. In his book A Christian Manifesto, he wrote, “We, who are Christians, and others who love liberty, should be acting in our day as the founding fathers acted in their day,” without reckoning with the racially limited aperture through which liberty could be experienced then. To be fair to Schaeffer, he did decry the very notion of enslaving Black people. But he blamed Christians who built their justification for slavery on what he identified as secular philosophies, ignoring that many in the 19th century used the Bible, not secular ideas, to justify slavery.

My school was small—my graduating class was just 12 people—but it was part of a broader movement, with tens of millions of American adherents. For us, making public-school prayer illegal in 1962 represented a terrible backslide. Billy Graham, before he died, lamented that the Engel v. Vitale decision was representative of a “general trend in our society,” one that “is certainly away from God and against any public expressions of faith.” His son Franklin has remained strident, turning his aim during a Fox News broadcast earlier this year to teachers following the law: “Our educators have taken God out of schools,” he said, arguing that “our nation is worse” as a result. And he told viewers, “We need Christian men and women on school boards who can take control of their communities.”

For this sector of society, Coach Kennedy’s victory wasn’t just worthy of celebration. It was a moment to go on the offensive, to consolidate long-sought gains. Graham, whose organizations joined an amicus brief on behalf of Coach Kennedy, took to social media, writing, “This isn’t a time for Christians to roll over—it is a time to defend our religious freedoms so that they are not lost for our children and grandchildren.” The victory signaled to others that this was yet another example of God’s plan for America. Jason Yates, the CEO of the Christian voting-advocacy group My Faith Votes, said, “The high court’s decision is evidence that God is at work in our nation to see that nothing impedes the glory He deserves."

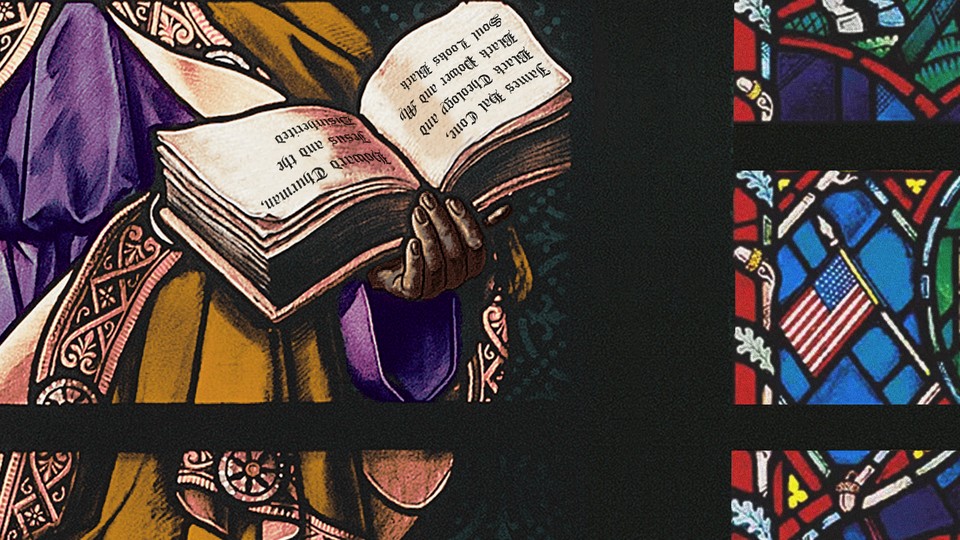

I couldn’t remain a believer in this American faith, because this American faith had no faith in me—a Black believer in Christ and the redemptive power of his sacrifice. To sit in those classrooms where my teachers obfuscated the true reasons for the Civil War and what the passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts meant was to feel alone in America. That loneliness sent me off in my own direction. I began to pick up texts at libraries written by authors who chose to mourn America’s failures with deep, religious conviction. Black scholars such as Howard Thurman, the author of Jesus and the Disinherited, and James Hal Cone, the author of Black Theology and Black Power and My Soul Looks Back, constructed space for me where my history books and my teachers had not. When I read Cone saying that “the Church knows that what is shame to the world is holiness to God. Black is holy, that is, it is a symbol of God’s presence in history on behalf of the oppressed man,” I found that my American faith had been replaced. I could no longer join their cause, the cause of those who have chosen to misremember our country’s history, one that valorizes the very people who would have seen me as less than what I am.

But they are the victors now, having crept their way into and established a foothold in our country’s jurisprudence. Their American faith has been vindicated; America seems to be their nation after all.