Anusha Alamgir would spend at least a day every fortnight in the dingy back alley markets of Dhaka, browsing through piles of secondhand clothing and lugging massive bags of used tops, skirts, and dresses in rickshaws. Onlookers would often stare at her continuously, perhaps wondering what she did with hundreds of items of castoff clothing that are shipped here from countries like Italy and Japan.

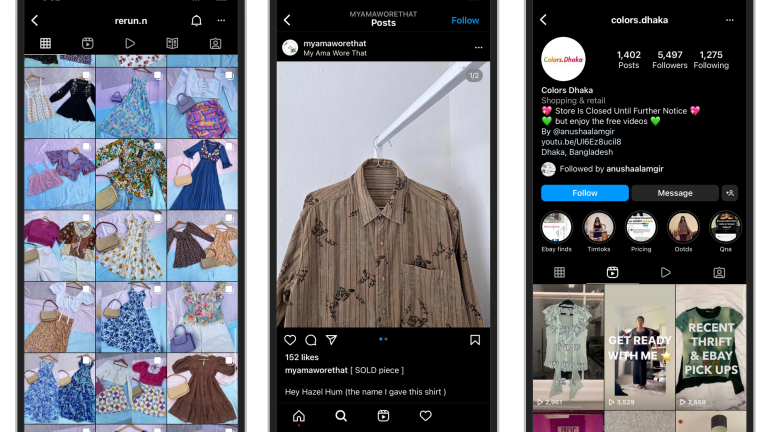

Alamgir sold these clothes through her Instagram thrift store, Colors Dhaka, which has more than 5,500 followers. (The thrift store is currently on pause as Alamgir is studying in the U.K.) Colors Dhaka was launched in October 2019 as a way for Alamgir to raise money for her book publishing business. What began as her selling items from her own wardrobe eventually turned into a profitable venture, earning between $200 and $2,100 each month, depending on how frequently she posted.

A few years ago, running a successful thrift store would have been unthinkable, as buying used clothes was seen in a negative light across most of South Asia. “This notion of being middle class or wearing other people’s clothing is seen as something that’s so taboo and so looked down upon,” Alamgir told Rest of World.

But Instagram, with its aesthetic visuals, low-entry barriers, and growth potential, has flipped this belief on its head. Across Asia, the changing attitudes of Gen Z and millennials have propelled the boom of the secondhand clothing market. Customers see used clothes as a cheaper and environmentally sustainable alternative.

Numerous Instagram-based thrift stores have emerged across India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal over the last three years, making the concept of secondhand fashion popular – even desirable – among young shoppers. These thrift stores have become a lucrative business for many young entrepreneurs. One Indian thrift store owner told Rest of World that if a dress sells for 850 rupees (around $10), including shipping, the profit margin could be as much as 500 (around $6) rupees.

Shah Mehsan Hafiz, a 26-year-old doctor from Dhaka who shops from Colors Dhaka regularly, said there is an individuality aspect of shopping thrift, since each product is one-of-a-kind. “[Alamgir] would include small notes telling me how to style and thanking me. She packages everything in eco-friendly parcels and sends them over on very short notice, conveniently. I love everything I got from her. I can’t say the same about my local retailers, sadly,” Hafiz told Rest of World.

The popularity of these Instagram thrift stores is growing so rapidly that Silvina Pradhan, who runs Dohoran Nepal, which has more than 8,500 followers and is one of the most popular thrifting pages in the Himalayan country, has upgraded her operations from her bedroom to a spare space in her parent’s home, where she plans to have a warehouse and a studio. She hopes to expand her business inventory capacity from 500 to over 5,000 pieces of Western clothing and vintage saris, all sourced from secondhand items discarded by local Nepalis.

Pradhan now employs a team of two part-time workers, one responsible for bookkeeping and dealing with buyers and sellers, while the other takes care of content planning and creation. “People in Nepal are still reluctant to shop through a website; they find the means of social media easier to buy and sell their products,” Pradhan told Rest of World. Although her team is building a website for Dohoran Nepal, she said the company will continue to focus on Instagram-based selling.

With the addition of short-form Reel videos on the platform, demands from customers have turned page creators into influencers. Delhi-based Yashna Malik and Ishita Bajaj, who run Revival Pile, an account with over 15,800 followers that sources from local factory and export rejects, sometimes offer styling tips via Reels and Guides. The two law school students with an interest in fashion developed Revival Pile during the Covid-19 lockdown, and now generate enough money to become financially independent.

Malik and Bajaj say they prefer Instagram to platforms like Poshmark because the social media network offers them a personal connection to customers.

“It’s not just a client-customer relationship,” Bajaj told Rest of World. The young people who message thrift store creators sometimes seek advice about how to style their clothes, starting a dialogue that determines the kinds of items the store creators source, and the content and trends the page follows. The two also believe that Instagram thrifting has democratized the distribution of fashion, since not all places across India have access to diverse markets.

The sellers take their role as influencers very seriously. “A lot of these customers are pretty young and they’re still trying to discover their sense of self,” Alamgir said. “You really shouldn’t entice them like that. As the creator… you have to prioritize the fact that these are kids that are spending money on your brand. You have to understand your power.”

After customers successfully book items through comments and messages on Instagram, shop owners coordinate with local delivery companies to ship packages. Cash on delivery is the common mode of payment in Bangladesh and Nepal, while digital payments are popular in India.

“Young kids [in Bangladesh] don’t have bank accounts,” said Alamgir. “I knew that Instagram was something where people could share and like things very instantly. There was already a built-in audience that was going to be seeing my things, because the algorithm would ultimately promote Colors Dhaka to my followers.”

But there are limitations to using a social media platform as a storefront.

Occasionally, Instagram’s algorithm becomes a hurdle. If a store owner posts too many “drops”– pre-announced limited edition clothing releases – Instagram labels those posts as spam, or blocks them due to vague community guidelines. The thrift store’s cohesively planned grid becomes disrupted as a post gets taken down. Glitches and failed “drops” mean customers fail to book orders, which can cause a loss of followers.

Half the Instagram thrift store owners who spoke to Rest of World said they experienced warnings that their posts violated guidelines if they posted more than 30 times a day.

“If you are thinking of bringing in big numbers, maybe Instagram is not the right way to go.”

Megha Luthra, who manages Rerunn, a thrift sale account on Instagram with 33,200 followers, said she only posts 25 items a day to her page, and showcases the rest on Stories. Luthra adds a question box in these Stories, and whoever sees the item and wants to book can reply within 24 hours.

“If you are thinking of bringing in big numbers, maybe Instagram is not the right way to go,” said Manish Jung Thapa, the owner of Antidote, a thrift store and clothing rental service in Nepal. The design of local online classified shopping platforms such as Hamrobazar are not optimized for selling clothing. As a result, Thapa has assembled a team to build an Antidote app.

As of January 31, 2022, Instagram has stated that it is unable to support the Shopping feature in India, which means advertisements run by creators still lead to traditional booking through direct messages and comments, rather than an automated checkout. Instagram declined to comment on when it might launch the feature in India.

Alamgir, who also wants to eventually open a physical concept store, has seen some thrift store owners in Bangladesh move from Instagram to TikTok live streaming for sales. TikTok, she said, is a lot more fast-paced and saturated compared to Instagram, and creators must promote their businesses daily to hold people’s attention and have the algorithm promote their content.