On the morning of 25 August 2014, a 16-year-old girl arrived at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in a baffling condition. She was short of breath but had no chest pain. She had no history of any lung condition and no abnormal sounds in her breathing. But when the emergency room doctor on duty pressed on her neck and chest, he heard noises like Rice Krispies crackling in a bowl of milk. Spaces behind her throat, around her heart and between her lungs and chest wall were studded with pockets of air, an X-ray confirmed, and her lungs were very slightly collapsed.

The doctors were confused until she said that she’d been screaming for hours the night before at the Dallas stop on One Direction’s Where We Are Tour. The exertion, they hypothesised, had forced open a small hole in her respiratory tract. It wasn’t really a big deal – she was given extra oxygen and kept overnight for observation and she required no follow-up treatment. But the incident was described in all its absurd, gory detail in a paper published in the Journal of Emergency Medicine three years later. The lead physician wrote that such a case had “yet to be described in the medical literature”. Doctors were familiar with military pilots, scuba divers and weightlifters straining their respiratory tract, but this case presented the first evidence that “forceful screaming during pop concerts” could have the same physical toll.This was a novelty news item: an easy headline and a culturally salient joke about the overzealousness of teenage girls. It was parody made real and recorded with the deepest of seriousness, for all time, in a medical journal. I know nothing else about the girl who loved One Direction so much that she collapsed her lungs over it. Her doctor wrote to me that he’d asked, at the time, for her permission to tweet at TV host Jimmy Fallon about the incident – he’d argued that maybe she would get to meet One Direction. “But she was too bashful!!!! Classic teenager,” he said, adding a laugh-crying emoji.

I’ll never know who she is or hear her personal explanation of what made her scream so much. In this specific circumstance, that’s because of medical privacy laws, which are good. But it’s also emblematic of a bigger lack: we have seen so many screaming girls. Every time we see them, we’re like, “They’re screaming”. And that’s it. Yet the screaming fan doesn’t scream for nothing and screaming isn’t all the fan is doing. It never has been.

At “Harryween”, Harry Styles’s “fancy dress party” at Madison Square Garden last year, fewer girls dressed to impress in the “fancy” sense than in the meme sense, signalling fandom knowledge of in-jokes and stories more than a desire to look attractive. My sister dressed as Harry Styles working in a bakery in England in the 00s, while I dressed as the shrine that one fan erected at the site where Styles vomited beside the 101 freeway in Los Angeles in 2014. Of course, part of my costume was confiscated by arena security because if you let one piece of posterboard into the arena you’ll end up letting a chaotic amount of posterboard into the arena – and no one will be able to see the show.

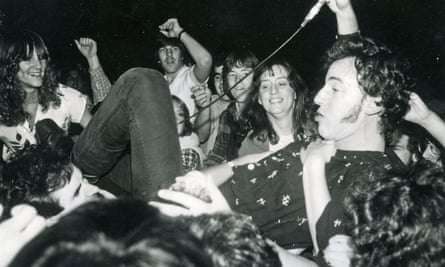

Reports about screaming girl fans – like those from Styles’s current tour, which kicked off last week in Glasgow – have rarely, if ever, noticed these kind of subtleties. When the Beatles visited Dublin for the first time, in 1963, the New York Times reported that “young limbs snapped like twigs in a tremendous free-for-all”. When they arrived in New York City in February 1964 – a little more than a month into the US-radio-chart reign of I Want to Hold Your Hand – there were 4,000 fans (and 100 cops) waiting at the airport and reports of a “wild-eyed mob” in front of the Plaza Hotel.

Nearly all of the writing about the Beatles in mainstream American publications was done by established white male journalists. Al Aronowitz, the rock critic best known for introducing the Beatles to Bob Dylan and to marijuana (simultaneously) in the summer of 1964, reported that 2,000 fans “mobbed the locked metal gates of Union Station” when the Beatles performed in Washington DC. Then, when the Beatles came to Miami, 7,000 teenagers created a four-mile-long traffic jam at the airport and fans “shattered 23 windows and a plateglass door”. A plateglass door!

“Being a fan is very much associated with feminine excess, with working-class people, people of colour, people whose emotions are seen as being out of control,” Allison McCracken, an associate professor and director of the American-studies programme at DePaul University, told me. “Everything is set up against this idea of white straight masculinity, where the emotions are in control and the body is in control.”

McCracken is an expert on the history of the “crooner” in American culture and her 2015 book, Real Men Don’t Sing, credits Rudy Vallée and Bing Crosby with making the blueprint for a pop sensation in the late 1920s and early 30s. McCracken visited the American Radio Archives, in Thousand Oaks, California, to see Vallée’s personal archive of fan letters, dating back to 1928. She was fascinated by the way the women who were writing to him were surprised by their own emotional reactions to his music and were confused by the idea of falling in love with a voice they’d heard only over the radio. “They were responding to his voice and saying, ‘I don’t understand why I’m so happy and joyous and why you’re moving me so much,’” she said. “They were writing to him and saying, ‘Can you explain what’s happening to me?’”

Though psychologists had in the early 1900s started describing adolescence as a unique stage of life, the word teenager itself wasn’t widely used until the late 1940s, McCracken explained, and the most eager speakers of the term were also marketers. They realised in the postwar boom years that far fewer kids were dropping out of school to earn money for their families and that far more were being given allowances and plenty of leisure time. The 1950s and 60s saw more and more products marketed explicitly to teenagers, often reinforcing the idea that they were a distinct group of people with a separate identity from their parents and with the rise of teen-marketed products came teen-oriented TV shows during which they could be advertised.

So long as teens existed as a lucrative market category, the industry would supply them with a teenybopper idol. When these idols were written about by journalists and critics, it was often with full acquiescence to their marketing, tinged with disdain. This was the case as recently as 2010, when the idol was Justin Bieber. When he performed his first sold-out show at Madison Square Garden that September, the New York Times music critic Jon Caramanica titled his review “Send in the Heart-throbs, Cue the Shrieks” and wrote that Bieber “teased the crowd with flashes of direct emotional manipulation”.

Two years later, One Direction were battling Bieber for the No 1 spot on the US charts, and in the hearts of American teenagers, and Caramanica started reviewing the band’s output with equal attentiveness. He called their 2012 second album, Take Me Home, “a reliable shriek-inducer in girls who have not yet decided that shrieking doesn’t become them”. He panned the band’s 2013 album, Midnight Memories, writing: “They play the part almost resentfully, with the mien of people who know better… Whether this is transparent to the squealers who make up their fanbase is tough to tell.”

This idea that fans are an amorphous mass and that culture is something that happens to all of them in the same way can be traced back to Theodor Adorno, whose 1938 essay, cited in the New York Times’s coverage of Beatlemania, described fans at live music performances as empty vessels: “Their ecstasy is without content.” Adorno’s work has been the starting point for the past 70 years of pop culture analysis, perhaps right up until the 1990s when cultural historian Daniel Cavicchi spent three years interviewing Bruce Springsteen fans about where their love of Bruce had come from and how it had coloured their lives for his book Tramps Like Us. At the time it was still up for serious debate whether the adoration of a pop star turned a person into an idiot. The cultural anxiety around popular culture then – which has relaxed now, even if it hasn’t totally disappeared – was that it was a homogenising force that turned every participant into a mindless consumer. But in speaking to hundreds of fans, Cavicchi found something different. These people were exploiting the ultra-popular things they loved in order to become more completely themselves. “Springsteen fans… do not indicate that popular culture is shaping their identity but rather that they are shaping their identity with popular culture,” he wrote.

What many commentators couldn’t – or wouldn’t – see was that fans have not just passively enjoyed or loudly desired the objects of their fandom. They’ve also edited them and recirculated them and used them as the inspiration for a range of creative works on and offline. The art, the stories, the fan fiction and the in-jokes are as much a part of what it means to be a fan as staking out an airport or memorising dozens of songs. Fans transform their own image by playing with expectations and flouting the rules; dress themselves up in the spirit of Harry Styles – indulging in elaborate cosplay – as an expression of devotion that is also a prolonged creative exercise. When Styles started wearing blouses and pearls and high-waisted trousers, so did they. They bought old-school rocker platform boots or knitted their own sweaters in the styles of his expensive, designer ones and expressed their fandom through aesthetic iteration.

There’s something else the critics didn’t realise: fan girls are funny. In 1964, a group of girls in Encino, California, founded an organisation they called Beatlesaniacs Ltd. It was advertised as “group therapy” and offered “withdrawal literature” for fans of the Beatles who felt that their emotions had got out of hand. In a 1964 issue of Life magazine, the group is covered credulously. (The spread on Beatlemania features a full-page image of a girl kneeling on the ground, grass clenched in her hand, tears streaming down her face – whether or not she was actually thinking, “Ringo! Ringo walked on this grass!”, that is how the photo is captioned.) The club is mentioned in a small sidebar, entitled “How to Kick the Beatle Habit”. “What Beatlesaniacs Ltd offers is group therapy and withdrawal literature,” it reads. “Its membership card immediately identifies the bearer as someone who needs help.”

The club was obviously a joke. Its rules included such items as “Do not mention the word Beatles (or beetles)”, “Do not mention the word England”. But nobody is primed to see self-critique or sarcasm in fans. Seeing them toy with their own image or recognise their own condition contradicts the popular image that has circulated for the past 100 or so years.

Take the story of the shrine to Harry Styles’s vomit. The facts are these: in October 2014, Styles went to a party at the British pop singer Lily Allen’s house in Los Angeles. The next morning, riding in a chauffeured Audi, in his gym clothes, on the way back from “a very long hike”, he requested that the driver pull over. On the side of the 101 freeway, just outside Calabasas, he threw up near a metal barrier, looked up and locked eyes with a camera.

The day they were taken, the photos circulated in tabloids and online, and a few hours later, a Los Angeles-based 18-year-old named Gabrielle Kopera set out to find the spot and label it for posterity. She taped a piece of posterboard to the barrier: “Harry Styles threw-up here 10-12-14,” she wrote in big letters. The grainy photo she posted first to her own Instagram circled the globe. It is referenced in articles about “the moment Harry Styles knew he’d made it”, which was supposedly the moment someone told him his vomit had been scooped off the ground and was up for sale on eBay.

At the time she took the shot, Kopera was bored: she didn’t have the money for a four-year university course so she’d stayed home to work and to study at a local community college while most of her friends moved away. Being a fan of Styles and One Direction made her feel as if she had something to do that wasn’t a chore.

She was surprised and confused by the way her photo was covered in the media, as if it was something more bizarre than a comedy routine she was performing, primarily with herself as the audience. “It was more a joke about my life than his,” she told me.

By the end of One Direction, the media’s treatment of the band’s music and its fans had changed significantly. In part, this was because of a rise in the estimation of pop music among critics and a new focus among content makers on women’s websites for celebrating almost everything any girl did as “inspiring” and “empowering”. Guilty pleasures were to be enjoyed, not insulted, and it was rude to call them guilty pleasures at all. It is inappropriate now to make fun of girls for screaming or boybands for existing or anybody for liking anything.

You could argue Harry Styles helped drive this cultural change when he appeared in spring 2017 on the cover of Rolling Stone, interviewed by the music journalist and Almost Famous writer-director Cameron Crowe. “Who’s to say that young girls who like pop music – short for popular, right? – have worse musical taste than a 30-year-old hipster guy? That’s not up to you to say,” he told Crowe. “Young girls like the Beatles. You gonna tell me they’re not serious? How can you say young girls don’t get it? They’re our future. Our future doctors, lawyers, mothers, presidents, they kind of keep the world going.” He really went for it. “Teenage-girl fans – they don’t lie. If they like you, they’re there. They don’t act ‘too cool’. They like you and they tell you. Which is sick.”

I’m happy that he said that, because I know it meant something important to a lot of people. But it’s hard to celebrate the fangirls’ coming of age the way I’d like to, because it is also being celebrated by the sort of people who will use it to make more money out of us. And it’s being celebrated by well-meaning people in sort of embarrassing ways – as if liking a boyband is a radical political act, the same way wearing well-designed T-shirts with punchy slogans on them is a sincere expression of feminism and Pantone creating a shade of red called “Period” is empowering for anyone who menstruates. Not all women are “our future doctors, lawyers, mothers, presidents”, I would love to tell Harry Styles. Not all women keep the world going!

But alongside the overenthusiastic “acceptance” lies an essential truth: the little indignities and the big disappointments of being young, of not finding the love you want or of not becoming the person you’d hoped – these things are tempered by fandom. Fandom is an interruption; it’s as simple as enjoying something for no reason and it’s as complicated as growing up. It should be celebrated for what it can provide in individual lives. What this is, exactly, is hard to know if you don’t bother to ask. It’s generally much more than a scream.

Kaitlyn Tiffany is a writer at the Atlantic. This is an edited extract from her book Everything I Need I Get from You: How Fangirls Created the Internet as We Know It, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux (£13.99). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply