Lana Del Rey and the Allure of Aestheticized Pain

With Born to Die, Tumblr became awash in soft-grunge imagery that romanticized self-harm and dissatisfied femininity. Some yearn for it today.

In DepthIn Depth

Illustration: Angelica Alzona

This story includes themes of self-harm, disordered eating, and nonconsensual sexual relationships.

It’s this time ten years ago, and my best friend Rachael is dancing at herself in her bedroom mirror. She is swaying to a suite of songs, caressing everywhere except her panty line. She is totally withdrawing into her own fantasy world. Lana Del Rey always turns her this way, I think, trying to muffle my curiosity with revulsion. (I’m a 17-year-old lesbian who, at this point, absolutely cannot understand Lana’s appeal.) She is singing things like “my old man is a bad man” and “it’s you, it’s you, it’s all for you” as she pouts her lips and grabs at her own throat. She is lost in the cinematography of her own desires.

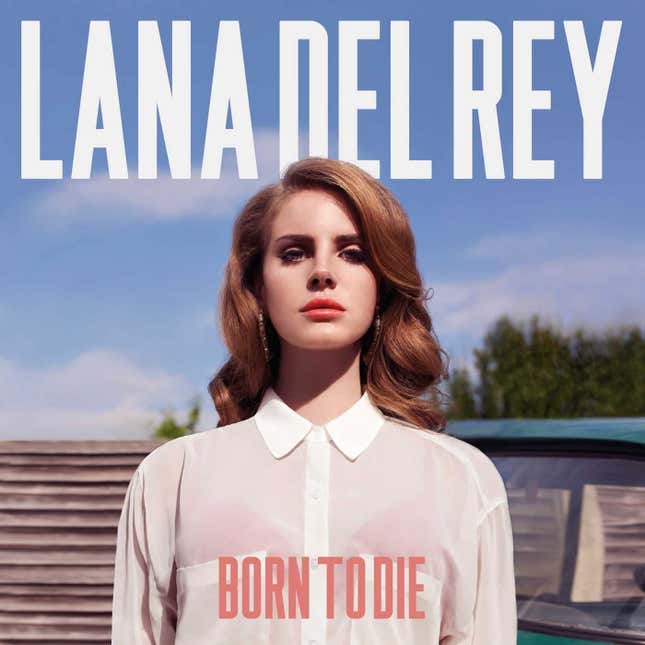

Born To Die, Lana’s second studio album, has just been released. It is an album full of self-destruction and willful submission, hellbent on a one-way death drive toward libidinal excess. It is also an album made by a recovering addict, one who hasn’t had a drink for nine years and is clearly nostalgic for the giddiness of mania. Lana lives out her alcoholism, addiction, and destructive tendencies through her art, populating the world of Born To Die with unsustainable fantasies: American maximalism, sadomasochism, too much liquor, older men, shitty men, unavailable men, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, money—as well as disappointment when those fantasies neither last nor materialize into real life. You can hear that tension in the music as she sings with a bored disaffection over soaring instrumentation.

With the album on repeat in the background, Rachael spends most of her days and nights on Tumblr, showing up to class wired on a dream-filled two-hour sleep. She often reblogs kink, sugarbaby, and nymphet content, as well as some images of self-harm and pro-ana (pro-anorexia). Lana plays a central role in each of these online communities, as they herald her as one of their own. Her love for daddies and older men (“I got sweet taste for men who are older,” she sings on “Cola”), her resistance to self-improvement (“I don’t wanna know what’s good for me,” she sings on “Gods & Monsters”), her mostly buried but nonetheless risqué lyrics on eating disorder culture (“I’m a fan of pro-ana nation/I do them drugs to stop the f-food cravings,” she sings on an old track called “Boarding School”)—not to mention her perfectly tacky glamor and hip-hop-meets-Old Hollywood high femme look—represent a new kind of dissatisfied femininity that is spread throughout Tumblr.

Ten years ago, the music Rachael danced to seemed to function like a Tumblr dashboard itself, Lana’s lyrics largely made up of petrified, recurring images: the American flag, Marilyn Monroe, gold coins, blue jeans, cognac, heart-shaped sunglasses. On entering that world, one’s emotions heightened, becoming fodder for an easily mimicked and coherent aesthetic on Tumblr known as “soft grunge.” Often filtered through pastel colors, soft grunge both beautified and subdued pain, making it consumable and even aspirational. Most of the images under the soft grunge rubric channeled illness, pain, and harm through a faded light, combining the cute with the abject. Parma violet-colored pills. Scars the shade of weakly drawn lines of water color. Bruises around throats where a hand had been, tones of twisted marshmallows. Lana in gif form with a pastel-colored flower crown on her head repeating the words “I wish I was dead.”

Now, a decade later, we seem to be living through peak Tumblr nostalgia, as the aesthetically symbiotic worlds between Lana and soft grunge Tumblr are being reimagined by Tiktokers and Girlbloggers. For many of the young women who spent their after-school hours online, trying to fantasize their way out of the mundanity of their teenage bedrooms, lockdown inspired a revisitation and a reckoning. Some grapple with the problematic context in which the Lana-Tumblr moment existed, where thinness was treated like divinity and self-harm brought in reblogs and engagement. Some yearn to return to it.

“I do vividly remember that after I started listening to Lana, the content I would reblog would be a more sensual, erotic BDSM, Lolita, soft blush pink sort of aesthetic,” Taylor (who, like most of sources in this story, goes by her forename to protect her identity) told me. She was part of Tumblr’s nymphet community a decade ago, while a sophomore in college. So too was Anna (a pseudonym), who says that while she ran a daddy-worshipping blog that she hid from her friends, self-harm was the only original content she ever posted on Tumblr in her young teens. She also was “guilty of browsing through [pro-ana] tags to try to find tips to lose weight quickly.” Her blogs, adorned with Lana Del Rey lyrics, were largely a form of escapism. “I used them as (unhealthy) coping mechanisms for past trauma and the mental health issues I was dealing with at the time,” she told me.

Since its 2007 beginnings, Tumblr has been a popular hub for blogs about self-harm, as well as disordered eating and suicidal ideation. It gave rise to a deeply confessional and earnest emotional register, possibly because the website felt so much like an enclave, a hidden corner of the internet where most users remained totally anonymous, finding community with others who shared a similar aesthetic and disaffection with life itself. Jenna, who was in Tumblr’s nymphet and pro-ana communities (a common overlap), told me, “For some people, you need to start off making sad posts to learn how to make friends online; it’s instant community.” Taylor wanted both that sense of community, as well as “a more romantic, indulgent life.” She found it in the nexus of Lana Del Rey-touting Tumblr blogs.

Much like Lana herself, the soft-grunge images of the time were both wildly popular and widely hated. Remember, this is back when Amy Poehler’s popularity was at an all-time high, Hillary Clinton was yet to be culturally acknowledged as cringe, and Katy Perry’s “Roar” was 2013’s song of the year; liberal feminism was tantamount to empowerment and health. In this climate in particular, Lana appeared unapologetically unhealthy. It’s unsurprising, then, that Born To Die was largely panned by critics who wrote that she was dangerous, that she glamorized terrible men and codependent relationships.

“I had the most cathartic realization ever: I can be sad and miserable and still make my life beautiful and worth living, even if just as a performance.”

Lana romanticized pain, and most people took that as a moral failing. But when your situation was one of unrelenting, inarticulate, unyielding, incomprehensible, inescapable sadness—how else were you to bear it than to glamorize it? How else were you to find others, who’d also yet to rearticulate their cry for help into an intelligible yelp, than to aestheticize your situation? Even ten years on, when the pained exhibit their pain, the world tends to act with revulsion and distrust. This was, and is, the Tumblr conundrum.

The Instagram user @chateaumarmontxx is one of today’s more renowned Girlbloggers—a new collective of aesthetes made up of Tumblr revivalists who are recreating the Lana era of Tumblr yore, bringing it to a new generation. “I think I was attracted to that imagery because it was a place where I wasn’t shamed for, or made to feel uncomfortable about, my own extreme sensibility or femininity,” she said. “When I first listened to [Lana] I had the most cathartic realization ever: I can be sad and miserable and still make my life beautiful and worth living, even if just as a performance.”

Helena, another of today’s Girlbloggers, says that she was drawn to Tumblr and Lana because she considered them antidotes to a false and invasive wellness culture. “Both Lana and Tumblr became the most popular at a time when feminism meant having a very positive attitude towards womanhood, being independent, wanting power, ‘self love,’” she said. Unlike the empowerment-core artists of the time, like Perry, Kelly Clarkson, and Taylor Swift, Jenna told me that Lana was different because Lana was not interested in being a savior, “and I think people found that particularly uncomfortable.”

While being sad and performing a kind of self-destructive impasse on the internet preceded Lana—“I would tweet lyrics from emo bands between sharing MyFitnessPal screenshots before I later reblogged gifs of Lana between photos of thighs,” recalled Jenna—Lana-era internet sadness invited more disdain than ever. Heavy pushback could be seen on Tumblr itself, in Boomer outcry, and in numerous thinkpieces. “I think there is an element of people hating things that teen girls like here,” said Jenna. “People want to protect girls from media that might make them go wayward, when going wayward is just part of growing up sometimes.”

In late February 2012, less than a month after the release of Born To Die, Tumblr announced that it would ban self-harm blogs. “Don’t post content that actively promotes or glorifies self-injury,” it wrote. However, “joking that you need to starve yourself after Thanksgiving or that you wanted to kill yourself after a humiliating date is fine,” it advised. Exhibiting pain was okay so long as it was de-aestheticized and poked fun at.

Many of the self-harm and self-harm-adjacent blogs survived Tumblr’s initial ban, but Jenna noticed a turning of the tides sometime around 2016. While scrolling through her Tumblr archives, she saw that her once sentimental, soft-grungey page had become ironic jokes and shitposts, though still with Lana’s lyrics captioning them. The communities on Tumblr who had once turned their pain into romance began turning their pain into self-deprecating punchlines instead. They became too self-aware; the fantasy died, leaving those who depended on it as a form of escapism to seek nostalgia instead.

Today, as Lana herself appears to be the independent, empowered woman 2012 so desperately wanted her to be (despite multiple stumbles), singing about trading in violets for roses, this is how most of us perform our suffering on the internet. We turn our pain into ironic punchlines and treat seriousness unseriously. Captioning a photo of a minion with “I’m suicidal lol,” for example, is commonplace and fair game, but posting a black-and-white crying selfie with Lana’s lyrics overlaid would end up on a shitposting page like @on_a_downward_spiral. “I used to go to Tumblr to read deep, pretentious shit, and I still do, but now I just laugh about it as well,” said the user behind @chateaumarmontxx.

Anna, like most of the people I spoke to for this article, said that the way she expresses her pain online is in alignment with whatever style invites the most engagement from the online community. “I am someone who shitposts about my mental health now, and I know deep down that I am just using humor to deflect my problems so I don’t actually have to deal with them,” she said. “At the same time, aestheticizing my pain back then made it almost seem desirable…like I would lose part of who I was if I healed and became happy or healthy.”

“People want to protect girls from media that might make them go wayward, when going wayward is just part of growing up sometimes.”

Even though their mode of expression has shifted, the influence of Lana Tumblr—a place where young women and girls were able to “identify and articulate feelings, desires, and needs in a way [they] hadn’t been able to before,” as Taylor called it—is undeniable. Some say they miss it. “I can still feel myself—especially in this lockdown with nothing to do, and during university when I made the wrong friends and I was bored—wanting to live that fantasy world,” said Jenna. “But the world isn’t real, and you end up sitting in a room, in the dark, in a silk dress depressed out of your mind.”

As “the culture”—one of Lana’s favorite phrases—has largely de-aestheticized the way we exhibit pain, I can almost understand the allure that Lana Tumblr, a communally imagined world of pastel-pink, scars, thin bodies, and Lolita sunglasses, had on my friend. It was an escapist fantasy of pain and desire in which to dissolve.

As we remain in the soft-pink, nostalgic glow of Lana Tumblr, it’s important to question exactly what we’re longing for, and why. Is there no longer a digital space to truly communicate pain, where romance and fantasy like the kind you found on Lana Tumblr are encouraged? Should there be? Looking back on it now, I feel homesick for a time I personally didn’t live through. I wish I could see my friend spinning in front of that mirror, like a gif, forever.

Emma Madden is a writer based in Brighton, UK. They have written about music and digital culture for The New York Times, GQ, Pitchfork, and many others.