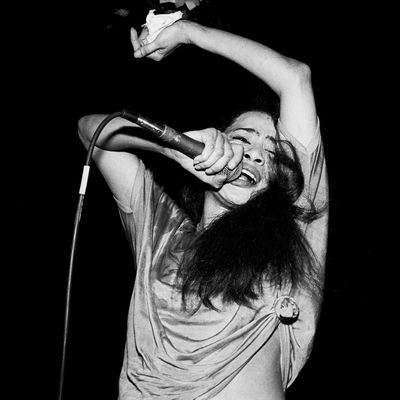

The first time Ronnie Spector, who passed away this week at age 78 after a short bout with cancer, altered the course of music history it was as the central voice of the essential 1960s girl group the Ronettes. With hair teased up to the heavens, dramatic black eyeliner, and skintight outfits, the Ronettes — the name the family act stuck with after stints as the Darling Sisters and then Ronnie and the Relatives — transcended the art of hitmaking. They set trends. What was originally a gimmick the girls developed to help them get noticed became a defining, definitive image that would be lovingly emulated and borrowed from throughout the decades to follow.

Born Veronica Bennett on 151st Street in Spanish Harlem, Ronnie’s distinctive vocal style, hallmarked by her instrument’s clarity and range combined with her ability to imbue each note with a tangible emotion, surfaced as early as 4 or 5 years old; soon, she was climbing on the coffee table in her living room — along with her older sister Estelle and cousin Nedra Talley — to perform for her extended family. Ronnie wanted to be a star and the girls jumped on every possible opportunity to get there, be it performing at bar mitzvahs, talking their way into a slot at amateur night at the Apollo Theater, or dressing up and going to the Peppermint Lounge, where they were mistaken for go-go dancers, and peppermint-twisting their way into an official gig at the famous rock-and-roll nightclub.

The girls had already made a few singles for the Colpix label, but it wasn’t until a gig opening the Peppermint Lounge’s outpost in Miami that they met influential disc jockey Murray “Murray the K” Kaufman, who curated epic packages of rock and roll, soul, and R&B groups into all-day extravaganzas at the Brooklyn Fox. The Ronettes began under Murray as eye candy, dancing in the background and serving as the straight women for Murray’s snappy patter between sets, but their talent and hustle were undeniable; quickly, they worked their way into singing backup for groups without backing singers (or whose backing singers weren’t very good).

In 1963, they joined forces with the inventor of the Wall of Sound, producer Phil Spector, through the most prosaic of methods: They cold-called him. While Spector (who loved a gimmick) made it seem like they had hit the jackpot, the truth of course was that he had seen them at the Fox many times. At their audition, Spector asked them to sing the kind of thing they’d do for fun. Ronnie didn’t get through the first line of “Why Do Fools Fall in Love” — the 1950s hit by doo-wop marvel Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, whose voice Ronnie adored and strove to replicate standing on that living room coffee table all those years ago — before Spector interrupted them. “Stop! That’s it. That is it! That is the voice I’ve been looking for,” he yelled, as recounted by Ronnie in her 1990 memoir, Be My Baby. The rest is tempestuous history.

The Ronettes went on to have nine top-ten hits working with Spector, and also sang on the producer’s now-classic A Christmas Gift for You. Ronnie and Phil wed in 1968 and the marriage lasted four years, during which time Spector was infamously violent and abusive, subjecting her to physical and emotional torment and threats, refusing to let her leave. She finally managed to escape from their house, barefoot and with the clothes on her back, with the help of her mother. Spector continued to try to inflict harm on her, both professionally and personally, for decades afterwards. Upon his death in January 2021, she wrote, “As I said many times while he was alive, he was a brilliant producer, but a lousy husband.”

Ronnie Spector’s work, both with and without Phil, remains a vital resource. Despite struggle and hardship, she never lost the qualities that made her voice wrap around your heart, and no one has ever been able to imitate her unforgettable tone and delivery. It’s no surprise that such talent inspired her peers and future generations alike to try to match her impact, or that people who grew up on her music and then became musicians themselves wished to reciprocate what they took from her work by helping her reclaim the spotlight that she rightfully earned, but that her former husband had tried relentlessly to diminish.

Here are just some of the best moments of Ronnie Spector’s historic career.

“Be My Baby” (1963)

There are endless elements that make this song timeless — the arrangement! The production! The performance! The lyrics! — but there is only one reason there are zero good cover versions of it, owed to the way Ronnie’s voice conveys the unconscious throbbing of a heartbeat. It’s a mixture of love, adoration, and longing in its purest sense, and it’s capped off by the unforgettable whoa-oh-oh-oh that became her trademark. There tends to be an understandable focus on Ronnie’s vibrato, that vocal modulation in the whoa-oh-ohs, but it isn’t the existence of the vibrato that makes her voice so captivating. Rather, it’s how she uses it to deliver emotion, to express the inexpressible — and for a song written for teenagers and about youthful love, there’s a lot of things you don’t have the words for yet. Here, Ronnie gives a voice to it.

“Say Goodbye to Hollywood” (1977)

Billy Joel wrote it with Ronnie in mind and tried to sing it like her, and that was going to be the end of it, until Steve Popovich, a fan and executive at Epic Records, found it in a pile of demo tapes (Joel’s Turnstiles hadn’t been released yet) and realized it would be just the thing to revitalize Ronnie’s career after her acrimonious split from her ex-husband, as well as give some much-needed work to Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band, themselves sidelined while their Boss was tied up in a lawsuit against his former manager. Ronnie said that she wanted it to be the best record she ever recorded; if it was a hit, she thought, she’d be able to restart her career, now that she was no longer married to Phil Spector. It was produced by Steve Van Zandt, who had the best knowledge of how to work effectively with Ronnie’s voice; she’s backed by a band completely thrilled to be performing with one of their idols, and you can hear it. It should have been a hit; it’s a match made in heaven, the kind of Wall-of-Sound-But-Make-It-Our-Own production that this group of individuals excel at, and Ronnie sells it beautifully and with total precision.

“Walking in the Rain” (1964)

Ronnie recorded this in one take! One take! As a vocalist she embodied so much prowess that she could walk into the studio, put on the headphones, and immediately give full focus on the quality of the emotion required of the performance. It feels loose and daydream-y but endlessly hopeful, perfect for the song. As Ronnie told the story. when she came to the studio to lay down the vocal, she was surprised to hear how Phil Spector and Larry Leine had mixed the rumble of the thunder and the sound of the rain into the song’s intro, and how it helped her step into the song — “I was in a whole other world,” she recalled. She thought she was just singing a rough demo to get a sense of the song, but when she finished the song and opened her eyes, Spector said, “We can go home now.” She wanted to do it again, but after listening, agreed with his assessment: It was indeed a perfect take.

“Baby, I Love You” (1963)

The original is canon, opening with that whoa-oh-oh-oh; it sounds smoother, because Ronnie, at this point, is now more comfortable in the studio; it’s less teenage yearning than a delightful statement of intent. Listen to the way she revs up the emotional intensity of her plea as the song progresses — it’s a master class in vocal control and modulation. Trivia: Nedra and Estelle aren’t on this one (it’s complicated) so you’re hearing Darlene Love, Cher, and Sonny Bono on backing vocals.

“Work Out Fine” (2006)

Here, Ronnie sings the Ike & Tina Turner duet with Keith Richards, and it’s delightful to hear the two old friends work together because the teasing banter set up by the song’s lyrics is completely believable. The Ronettes took care of the Stones when they were first trying to make it in the States — there are stories in Ronnie’s memoir about them coming to have breakfast at her house in Queens and how her mom would make them eggs — and Keith got to do the honors to induct the Ronettes into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2007. (He’s even written a new foreword to a reissue of the memoir, which will be published later in 2022.)

“She Talks to Rainbows” (1998)

Joey Ramone produced this five-track EP for Ronnie as a labor of love. She covers two Ramones songs, “Bye Bye Baby,” a duet with Joey, and the title track, a wonder on which she takes the original composition to a deeper level of pathos. While they both are singing in third person, Joey’s perspective is from the outside looking in, while the pathos in Ronnie’s voice is almost tangible: “She’s a little lost girl in her own little world / She looks so happy but she seems so sad” has always felt like it derived from her time in Los Angeles after her marriage, where she wasn’t singing any more and was stuck inside her husband’s mansion. She also covers the Beach Boys’ “Don’t Worry Baby,” the song that Brian Wilson wrote in response to the first time he heard “Be My Baby,” and delivers a heartbreaking version of Johnny Thunders’ “You Can’t Put Your Arms Around A Memory,” one of those deeply emotional songs about loss and survival where there’s an almost unearthly vibe. For any other singer, that’d make it a challenge to interpret — but she does and it lands as deeply as the original. Her version here just proves that Ronnie Spector could sing anything.

HONORABLE MENTION: “Take Me Home Tonight,” Eddie Money (1986)

No, this isn’t a Ronnie Spector song, but it is one of the greatest rock-and-roll cameos ever, and whether you like Eddie Money or not, its composition and the intent is complete genius: “Take me home tonight / Just like Ronnie says,” Money sings, before cutting to Spector herself: “Be my little baby.” She reappears later in the song, for another couple of lines, and to let loose that glorious whoa-oh-oh another few times as the song draws to a close.