The Los Angeles police department targeted the late rapper Nipsey Hussle’s street corner and his The Marathon Clothing store before his death in 2019, labeling the intersection a “hot spot” for crime and sending special patrols that stopped and questioned people in the area, according to records reviewed by the Guardian.

Hussle, whose name became synonymous with the corner of Crenshaw Boulevard and Slauson Avenue, spent years investing in projects in the area until he was fatally shot at the intersection in March 2019. City leaders publicly mourned the artist and entrepreneur, but it was revealed soon after his death that LA law enforcement leaders had been quietly targeting his businesses with a criminal investigation, alleging it was a site of gang activity.

Internal records obtained by the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition and shared with the Guardian shed new light on how LAPD invested resources into policing at Crenshaw and Slauson, suggesting that for years the department focused enforcement efforts around the community gathering spot where Hussle had bought commercial space and was working to redevelop a corner strip mall.

The files, which were acquired through public records requests, are part of the coalition’s new report on “data-driven” LAPD initiatives that will be released on Monday. The report scrutinizes a controversial and now-shuttered LAPD program called Operation Laser (an acronym for Los Angeles Strategic Extraction and Restoration), which aimed to prevent crime and “restore peace”.

Launched in 2011, the program purported to use data to identify “chronic offenders” and specific locations linked to gun violence and gangs, in an effort to “extract” criminal activity from communities. But critics said the initiative was ineffective and biased, and that it enabled surveillance, racial profiling and harassment of Black and Latino residents, with little oversight. In the face of backlash, LAPD discontinued Laser in 2019, acknowledged its results had been “inconsistent”.

Samiel Asghedom, Hussle’s brother and business partner, told the Guardian he did not know of Operation Laser, but was not surprised to learn that the initiative focused on their store and the surrounding plaza: “It was a target point … It was like everybody walking out of the shop would get harassed or arrested.”

Mass stops at Crenshaw and Slauson

The full extent of the operation targeting Hussle and his businesses is unclear. Hussle had raised questions about the department’s activities in his community long before the start of the program – in a 2013 interview, he said officers would regularly stop and question people, and collect their information for no reason.

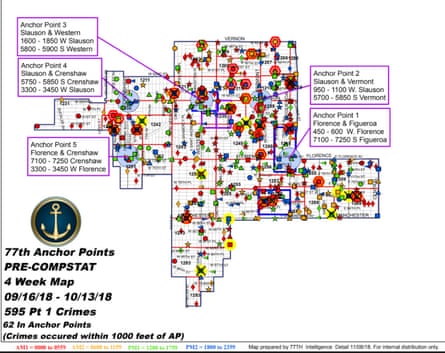

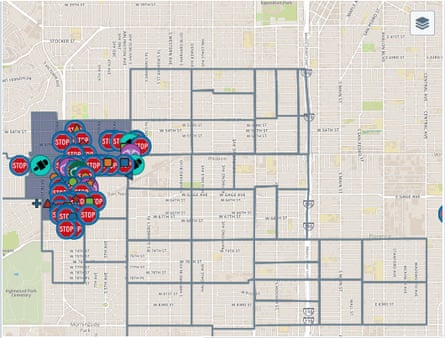

But it appears that LAPD first brought the Laser program to Crenshaw and surrounding neighborhoods in 2015, identifying six “zones” of interest (corridors that allegedly had high crime rates). Within those zones, LAPD selected specific locations to target, known as “anchor points”.

The Crenshaw and Slauson location was marked as an anchor point in 2016, one of about five locations targeted in the district. (By 2019, before the program was shuttered, the city had roughly 70 anchor points across LA, which included businesses, homeless encampments, parks, sidewalks and train stations.)

Hussle, who was 33 when he died, had deep ties to the plaza. “Age 14 on up – my whole life took place on these four corners,” he said of the intersection in an interview in 2010.

The artist and entrepreneur spoke openly about gang culture in the neighborhood and being a part of the Rollin’ 60s, a local Crips gang, at a young age. He also said he wanted to invest in economic opportunities for his community, with projects led by locals, instead of allowing outside groups to gentrify his neighborhood. Throughout the years, Hussle and his brother ran several stores on the corner, including an apparel store called Slauson Tees, which opened in 2006.

Hussle opened The Marathon Clothing store in 2017, with a launch event on 17 June. In the days after the grand opening, LAPD intensified its presence on the block, the internal records suggest.

A “patrol mission report” from 21-27 June suggests that officers were deployed to the “anchor point” at Hussle’s intersection in a crime “suppression” effort. During that week at the location and surrounding blocks, LAPD recorded 58 stops, but made only seven arrests, suggesting that for the vast majority of people stopped or detained, there was no probable cause to arrest them.

In a mission the following week, LAPD stopped 103 people, and made only three arrests; the records say LAPD was looking for a robbery suspect described only as a Black male between 16 and 18 years old.

The stops could carry serious consequences, even without arrest. As part of the Laser program, officers would routinely fill out “field interview cards” for civilians they questioned, even if they weren’t taken to jail, and would put their information into LAPD databases, which could later be used against them. Police across the city have allegedly used the cards to falsely label people as gang members and to collect their social media information.

“LAPD was speculatively criminalizing the location,” said Shakeer Rahman, a Stop LAPD Spying organizer and lawyer. The data that the officers collected could then be used to justify further targeting, he added: “Police are deployed to these locations, armed with what they’re told are these ‘data-driven trends’ … but those trends are just the racial profiling that police have always done.”

In one 2016 paper, the architect of the Laser program explicitly argued that LA crime data showed how certain violent crimes were “more likely to be located in areas where there is a higher percentage of African-American residents”.

Asghedom said LAPD had frequently harassed his family and passersby at the plaza in the years leading up to the 2017 launch, at one point arresting him while he was working at one of his shops on his birthday for a probation violation. But the police activity escalated dramatically after The Marathon Clothing launch, he said.

“It was like every ten minutes a [police] car is coming through the lot, and officers are hopping out. It was nonstop,” he said. In one instance, LAPD even stopped and questioned shoppers who appeared to be tourists, he said. The shoppers turned out to be off-duty police officers from out of state.

“It became, ‘Don’t come here if you don’t want police contact.’ If you did have a warrant, you ain’t coming to buy nothing from us. It was like, ‘Shit, I’m gonna get pulled over. I’m gonna get targeted,’” he said.

Asghedom said it felt as if the LAPD officers were angry about the success of the store, which was a source of pride for the local community and drew fans and supporters from across the US: “We’re here every day selling clothes, so there is less crime. This is something that y’all should be happy about. But instead, their whole goal was just to shut it down.”

The push to evict Nipsey Hussle

Operation Laser’s focus on Crenshaw and Slauson appeared to continue for years, with one October 2018 map included in the records specifying the Marathon store among a group of addresses as an ongoing anchor point.

The Stop LAPD Spying report also raises fresh questions about Los Angeles’ efforts to evict Hussle and his brother from the plaza.

After Hussle’s death, the New York Times uncovered that the city had been targeting his store as a “nuisance” property and the site of alleged gang activity, pressuring the landlord to evict the rapper and his business partners.

LA’s “nuisance abatement” program allows the city to file evictions based on alleged criminal activity at a property, and records show that the city considered evictions a key “strategy” to address issues with Laser anchor points.

Emails reviewed by the group also suggest that some city law enforcement officials had communications with developers in South Central and other parts of the city about eviction and enforcement efforts. The emails, the report’s authors argue, show that data-driven policing programs target areas with growing interest from real estate developers and have accelerated gentrification and displacement there.

Asghedom said that he and his brother had worked hard to make the corner of Crenshaw and Slauson a positive force in the neighborhood, and he argued that their shops had helped reduce crime in the neighborhood, not perpetuate it. Their landlord supported them, he said: “He was making money. We were making improvements to the lot. He tried to voice that to the police, and they didn’t give a fuck about none of it. They said, ‘We’re trying to label this as a city ‘nuisance’, and if you don’t sever their lease, we’re going to seize the lot from you.’”

Instead of evicting them, the landlord sold the property to Hussle and his business partners, which they considered a huge accomplishment, Asghedom said.

But even after Hussle’s death, the city continued to target the shop with a “nuisance” case, Asghedom said.

“It felt like a cat and mouse game. Their agenda was, ‘Whatever they are doing over there, crush it, stop it,’” said Asghedom.

It’s unclear to what extent that data collected through Laser may have been used to target The Marathon store for eviction in the final year of his life. The city attorney’s office, which was pursuing the eviction, declined to comment.

Over the years, they had serious discussions about whether to move the shop elsewhere, where they might face less police harassment. But ultimately, Asghedom said, his brother refused to leave Crenshaw and Slauson.

Asghedom said he and the other business partners eventually decided to temporarily close down the plaza, so that the city could no longer claim it was a “nuisance”. In the future, he hopes to reopen the Steve’s Barber Shop at the location, to give free haircuts to youth, and to launch a youth center there, along with some kind of museum or gathering spot where fans can pay tribute to his brother.

“Nip wanted to stay in the area and inspire the youth, and we want people to know this is something that Nip bought, knowing where Nip started and where Nip took it to.”

LAPD declined to respond to repeated requests for comment about the Laser program and the Marathon store.

LAPD’s deadly record in South LA Laser zones

Operation Laser’s reach in South Central went far beyond The Marathon Clothing. The Stop LAPD Spying report documents incidents of police violence that occurred in Laser “zones”, arguing that these surveillance and “extraction” tactics can be deadly.

Keith Bursey Jr, 31, was killed by an LAPD officer on Slauson Avenue, a block away from Crenshaw, on 10 June 2016. Officials said LAPD was in the area because 10 June was “Hood Day” when “gang members celebrate their gang”. Bursey was a passenger in a car that LAPD approached in a parking lot to investigate the “odor of marijuana”. Officers ordered the passengers to exit, and shot Bursey, hitting him in the back when he tried to flee, officials said.

“It seems like they were stopping anybody for any infraction that day,” said Cliff Dorsey, Bursey’s cousin, to the Guardian. Dorsey, a South Central native, who now works as a public defender, said he wasn’t familiar with Operation Laser, but that it aligned with the experiences of people in his neighborhood where LAPD gang operations rely on “guilt by association”.

LAPD frequently labeled South Central natives as criminal gang members based on their families and upbringing, Dorsey said. Bursey was not ashamed of his ties to the Rollin’ 60s, which family members had been a part of, but the gang did not define him and did not mean he was a criminal, Dorsey said: “It can be like family. These are young men that grew up in the same circumstances, surrounded by the same poverty, the same drugs. And they’re trying to survive as best they can.”

Mary Williams, Bursey’s grandmother who raised him, said her grandson was a talented tap dancer and football player and lamented that police stopped him that day “for no reason”. “They can’t just go around, harassing people and putting their names in databases. It was such an unnecessary murder.” She said that two weeks after the killing, one of Keith’s cousins was also stopped at the same intersection, without justification, and eventually released.

LAPD’s “data-driven” missions also targeted the Crenshaw mall, just north of Hussle’s store, which was labeled a Laser zone in 2015.

“This is a mall frequented by Black and brown people,” said Quintus Moore, whose son, Grechario Mack, was killed by police inside the mall in 2018 while suffering a mental health crisis. His son was holding a knife, but witnesses said he wasn’t threatening, and the police commission later ruled that officers violated policy when they shot him.

Moore said it seemed that the LAPD was often bringing new tactics and programs to his community and the area around the Crenshaw mall “because they want to try out their new gadgets and weapons in the Black neighborhood”.

While LAPD has launched efforts over the last decade aimed at improving community relations in South Central, Moore said it felt as if little had changed.

He said he had been unjustly pulled over twice while driving in the area in recent years – once when an officer peered into his car, and another time when an officer asked him if he had tattoos. Both times, after short interactions, he was released.

Johana Bhuiyan contributed reporting