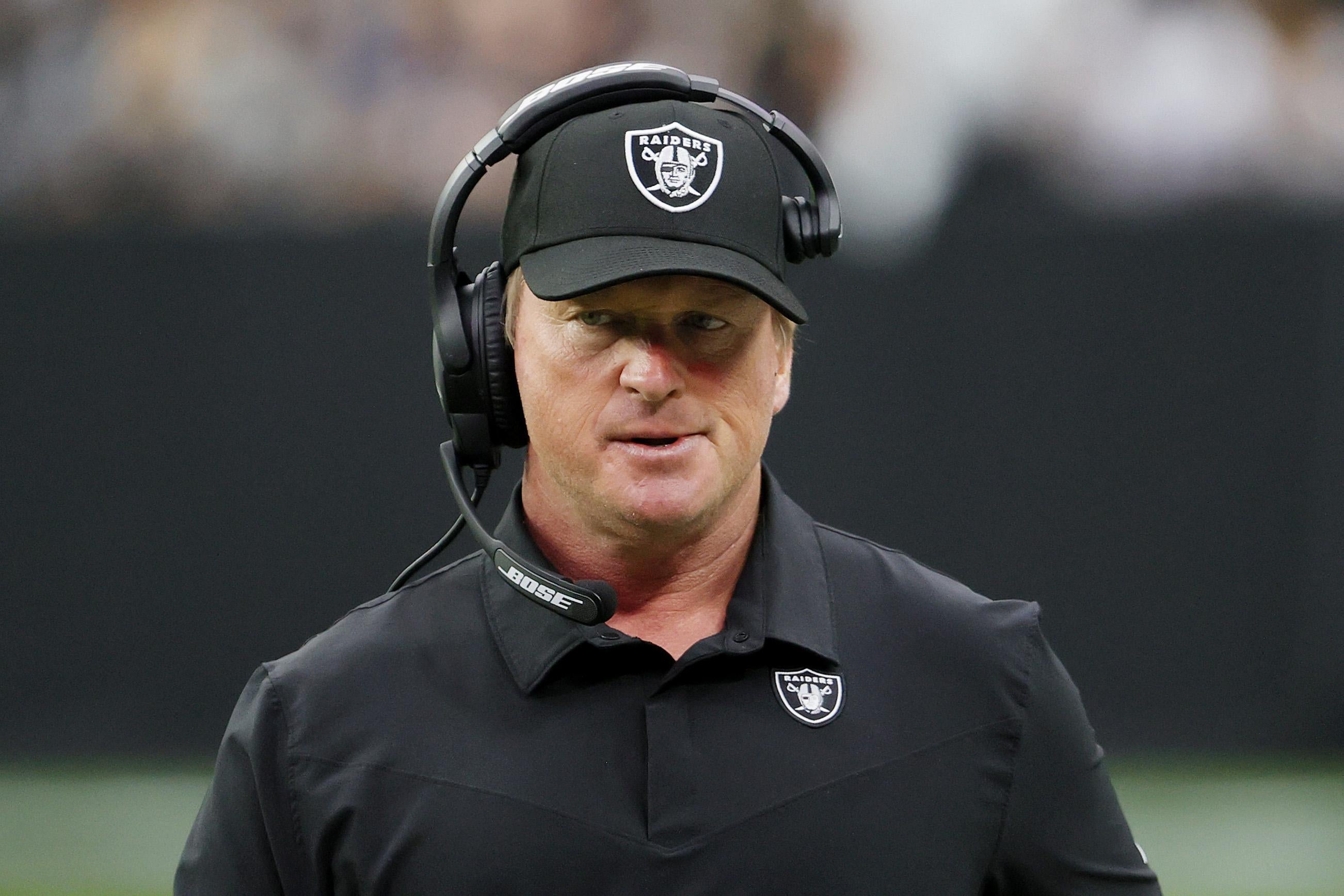

Jon Gruden, emails that he sent over several years have revealed, is a spitting image of the worst stereotype you had in your head of a meathead, authoritarian football coach.

First, the racism: On Friday, the Wall Street Journal surfaced a 2011 email in which Gruden, then a Monday Night Football analyst, said that NFL Players Association head DeMaurice Smith had “lips the size of michellin tires,” and called the union leader “Dumboriss.” By the day the story published, Gruden had been the head coach of the Las Vegas Raiders since 2018, on his second tour of duty with the franchise. He apologized and claimed he had not “a blade of racism in me.” The Raiders did not punish him, and he coached the team in a loss to the Chicago Bears on Sunday afternoon.

Then, on Monday, the homophobia and misogyny: The New York Times published excerpts from more Gruden emails sent over parts of seven years, up to 2018. Gruden called NFL commissioner Roger Goodell the anti-gay slur “f––––t” and a “clueless anti football pussy” and criticized him for pushing the St. Louis Rams to draft “queers,” a clear reference to 2014 draftee Michael Sam, the first out gay player that an NFL team had ever picked. The emails were part of exchanges with former Washington Football Team president Bruce Allen. Gruden’s brother Jay coached that team from 2014 to 2019, and Allen and Jon Gruden had worked together during Gruden’s first stint coaching the Raiders, from 1998 to 2001. The NFL discovered the emails between the two men during its investigation into the toxic work culture at the Washington Football Team, an environment that included bullying, intimidation, verbal abuse, neglect and dismissal of employee complaints, and rampant sexual harassment and denigration of women, including the team’s cheerleaders.

The Times story said the emails they exchanged also included “photos of women wearing only bikini bottoms,” including two Washington cheerleaders (who were Allen’s subordinates), as well as a request from Gruden to Allen to tell someone to perform oral sex on him. Gruden reportedly sent other emails that revealed him mocking female referees, criticizing players for kneeling during the national anthem, and criticizing Goodell for trying to reduce concussions.

The publication of that second batch of emails proved too much for Gruden to weather. On Monday night, almost immediately after the Times story hit, various NFL reporters said Gruden had told his team he would resign. For the first time in some of his players’ lives, Gruden will not have an official place in the NFL or in its immediate vicinity. The league, ever image-conscious, is likely relieved. When Gruden’s email about Smith came to light, a league spokesman, Brian McCarthy, called it “appalling, abhorrent and wholly contrary to the N.F.L.’s values.” The league never intervened, but now it won’t have to publicly square various “Football Is for Everyone” commercials and “END RACISM” sideline decals with Gruden’s continued employment.

The biggest problem with Gruden’s remarks, as the league should be concerned, is not that the ex-coach does not represent the NFL’s ideals. It should be that with every breath he draws, Gruden exhibits those ideals almost by default. Gruden is a more comprehensive encapsulation of an NFL poster boy than almost anyone else on Earth. That a man in his position would crumble in this fashion says more about the league itself than Goodell could ever admit.

Short of sitting in the commissioner’s chair, there isn’t much Gruden hasn’t done in his NFL life. He’s been in or immediately connected to the league since 1992 when he was a Green Bay Packers assistant. He was the Raiders’ head coach by 1998, when he was 35. He led the Tampa Bay Buccaneers to a Super Bowl in 2002. The franchise fired him after 2008, but that somehow only had the effect of making Gruden a more prominent fixture around the sport.

From 2009 to 2017, he was a booth analyst on Monday nights for ESPN. The telecast cycled through various play-by-play commentators and sideline reporters in those years, but Gruden was a constant, as well as one of the highest-paid people in the history of sports media. Gruden’s celebrity swelled in these years. His “Gruden Grinder,” the honor for nonstar players who showed out, became a mini-institution. He was a national pitchman for Corona and Hooters. Comedian Frank Caliendo’s Gruden impersonation was one of the earliest viral sensations of the sports Twitter age, and it was funny because people knew Gruden.

In his media perch, Gruden was part of the league’s unofficial welcoming committee for new players through his Gruden’s QB Camp series on ESPN. He’d sit in a room with quarterback prospects getting ready to enter the league, and he’d coach them up for the world to see. He’d talk with them about mental toughness and their life stories, like with Russell Wilson in 2012. He asked them how they’d handle the NFL circus and focus on their responsibilities, like with Johnny Manziel in 2014. His shtick was part football coach, part purveyor of wisdom.

To lure him back to the coaching ranks in 2018, the Raiders went as far as considering offering Gruden an ownership stake in the team, Gruden’s ESPN colleagues reported. They settled on a 10-year, $100 million deal, reported to be the largest by total value in league history (though NFL coach contract details are not routinely made public like college deals). When he took the job, he rejoined a head coaching club that by that time had multiple former assistants of his as members: the Rams’ Sean McVay, the San Francisco 49ers’ Kyle Shanahan, the Pittsburgh Steelers’ Mike Tomlin, and Washington’s aforementioned Gruden brother, Jay, who worked as Jon’s assistant coach in Tampa Bay. Gruden himself is part of an even larger Mike Holmgren coaching tree, underscoring the extent to which coaching is a network.

Gruden’s allies are situated all over the sport, including in its media apparatus. The vociferous defense that NBC’s Mike Tirico and Tony Dungy gave of Gruden on Sunday, before the second emails story came out, was instructive on its own terms. Dungy, another coaching lifer who preceded Gruden in Tampa Bay 20 years ago, urged people to accept Gruden’s apology and “move on.” Tirico, Gruden’s former broadcast partner on MNF, said he probably knew Gruden “better than anybody in the league, on a personal level.” Tirico said he never experienced or saw racism from Gruden when they worked together. That was before the second round of emails, which included blatant homophobia. (Dungy has his own history of homophobic remarks.)

The NFL is a lot of things. Among whatever else, it’s a fraternity, a made-for-TV spectacle, an advertising platform, and a place for coaches and executives to fancy themselves molders of young men, builders of people into something bigger than themselves. Most people in the league’s orbit do not get to wear all of those hats at different times, but Gruden did. Few have navigated from NFL station to station so seamlessly or for so long. Along the way—and it’s worth pointing out, some of these emails are less than four years old—Gruden decided he was comfortable sending a cocktail of shitty emails about people who were already fighting battles Gruden will never have to fight.

Gruden seemed determined to survive after his first racist email came out, despite knowing what else he’d said—a particularly audacious posture for the coach of the Raiders. As my colleague Joel Anderson pointed out, the franchise has a unique history of hiring minority trailblazers: The Raiders were the team that hired coaches of color in Art Shell and Tom Flores, and female executive Amy Trask. The Raiders also currently employ the first out gay player to make an NFL roster, defensive end Carl Nassib. Consider how comfortable Gruden needed to be in pro football circles to see any chance he’d make it through.

The answer: pretty comfortable. On the one hand, the emails showed poor judgment. How could he not see the risks to his own career of memorializing these thoughts in writing? On the other hand, though, there’s no reason to doubt Gruden’s judgment at all. He sent those emails because he didn’t figure his audience, which included the president of an NFL team, would have any big issue with them. For years, he was right. Gruden wasn’t an affront to the NFL as much as an embodiment of it.