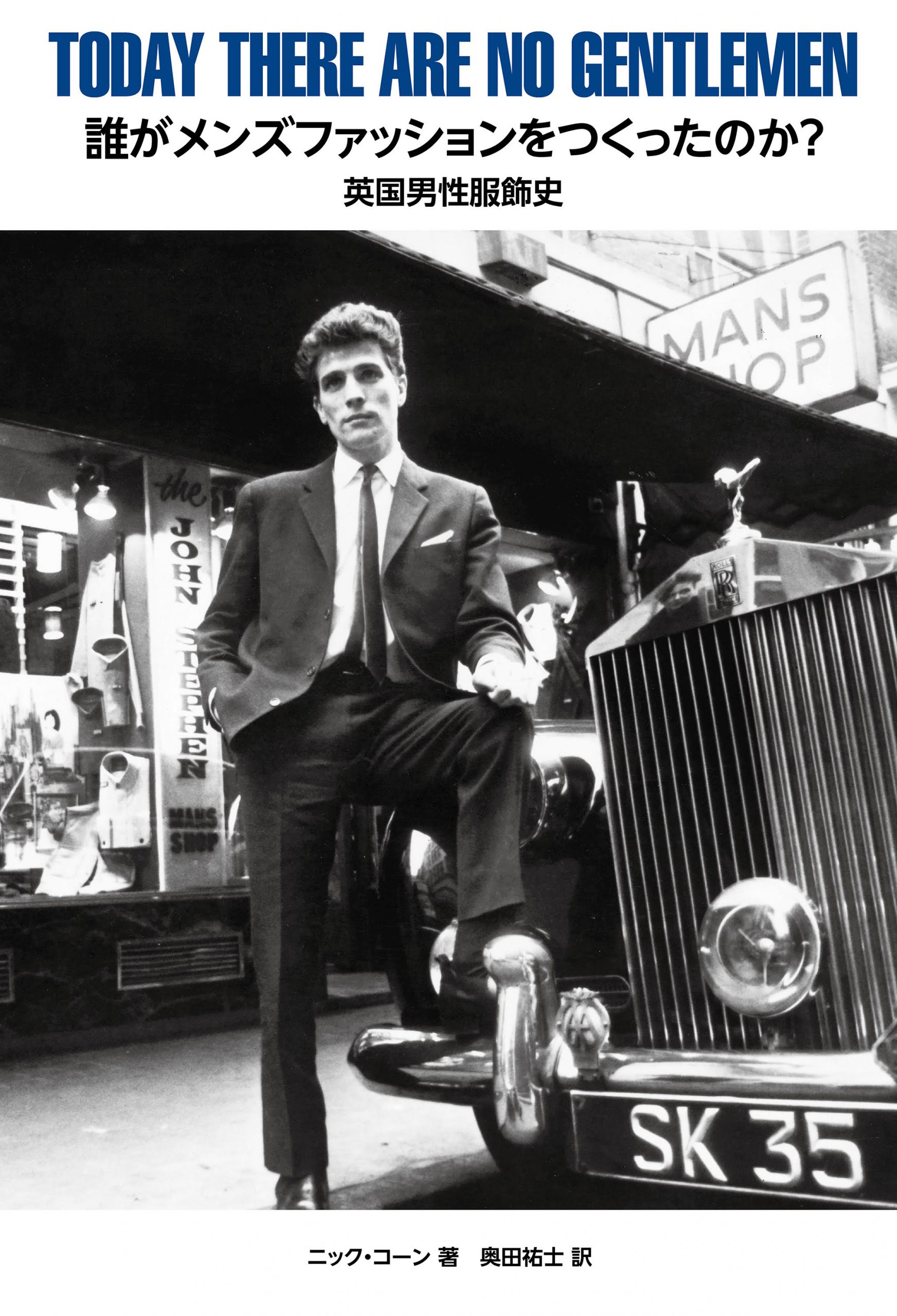

London, 1971: fifty years ago, Nik Cohn wrote the first great text on men’s fashion. Today There Are No Gentlemen— which took its title from a line offered by a dejected cobbler— brilliantly illuminated changes in the clothing of English men after the second world war. Cohn, only twenty-five when the book was finished, was gathering information in the wake of 1969’s Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom, an explosive text that discarded mainstream opinion and declared the spirit of rock dead while reflecting on the movement’s original pulse. With invaluable experience chronicling the London music scenes of the ‘60s, the critic-cum-storyteller was prepared to write a book that approached fashion seriously, with vivid depictions of subcultures emerging and clashing, shop owners swiftly redefining neighborhoods, and working-class youths spending their last coin on tailored suits.

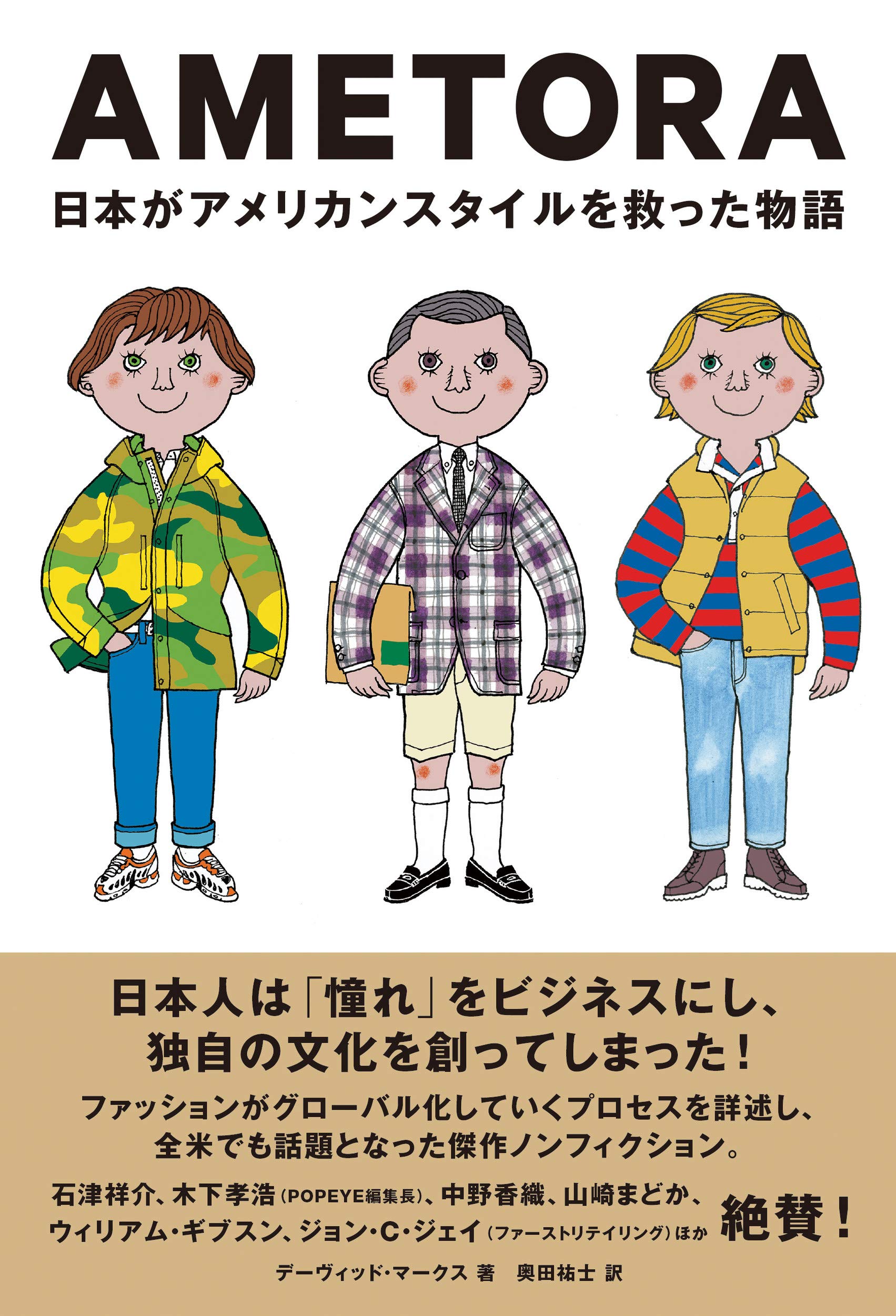

Last autumn, Today There Are No Gentlemen returned to bookshelves for the first time ever since its publication— in Japan, exclusively. W. David Marx, who wrote Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style, was the driving force behind the new life of Gentlemen, yet he had never spoken to Cohn. I was able to bring the two together to discuss Cohn’s book— what does it mean today, in Japan and beyond?

Right: David Marx

Right: Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style

The context of Today There Are No Gentlemen and its Japanese translation.

David Marx: In 2015, Ametora was published. Nick Sullivan, the fashion editor at Esquire, somehow got a copy— I don’t know if he bought it or if it was sent to him — he posted a photo on Instagram, and he said, I’ve only read the first page, and this is the best book about men’s fashion since Today There Are No Gentlemen.

Nik Cohn: [laughs]

Marx: And I said wow, Nick Sullivan likes my book…and then I thought, wait a minute, what is Today There Are No Gentlemen? I had never heard of it. I immediately looked it up, and the few used copies were going for $900, which dashed my hope of just quickly grabbing a copy to read. I ended up having a friend at a library who scanned the entire book for me and sent it over as a PDF. When I finally opened it up and started reading it, I was shocked about how close it was to Ametora in terms of methodology and story. It really felt like you had done what I had done, but forty years before…and I was embarrassed that I hadn’t known about the book, or read it, or referenced it.

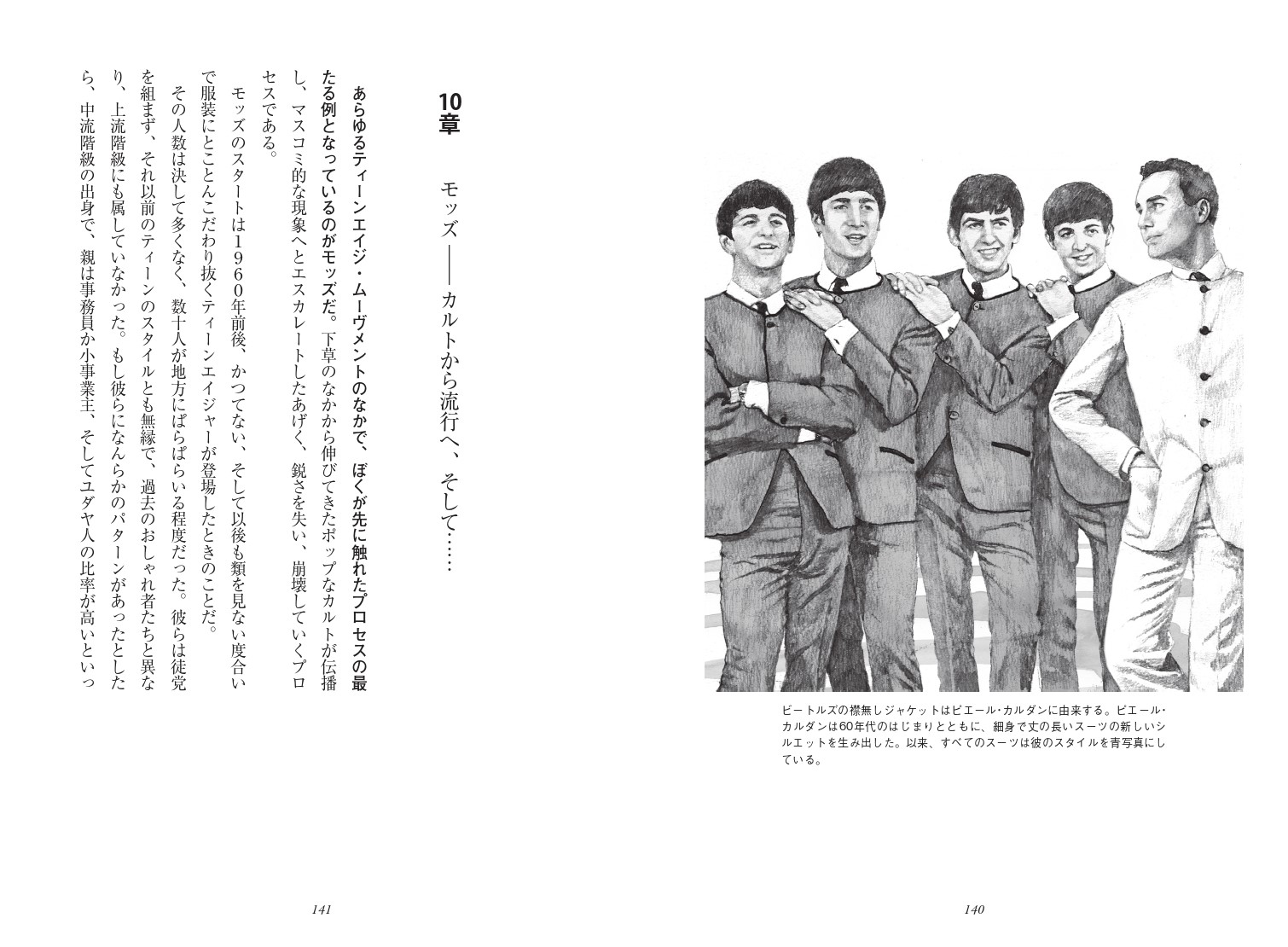

What I often complain about with fashion books is that they talk about trends just magically appearing. One day there are mods, and one day there are skinheads. Your book, because it was written in almost real time, talked about the specific people who did the things that led to these groups: the specific stores, the specific designers. Even in the case of subcultures, you talked to the original kids who became mods. With Ametora, I was also trying to show that cultural movements don’t come out of nowhere: They come from specific people.

I thought Today There are No Gentlemen was such a valuable piece of fashion history, and I wanted to see if I could help bring it back in print. I couldn’t figure out how to do this in English, but once I located your agent, Nik, I realized I could help a publisher in Japan get the translation rights. So I spent about a year pitching the Japanese publisher of Ametora, Disk Union Books, on a translation, and we then went to work on the translation. The translator for the Japanese edition of Gentlemen had done Ametora, and I helped him by reading through the text and identifying things that I knew would be difficult to translate, like 1950s British idioms. (Like “Super-mac” being Prime Minister Harold Macmillan). I did all that work and looked over the translation, then I wrote a preface to the book, to explain why I thought it was important.

The reason I wanted the book to come out again is that I think there’s more audience for this book now than in 1971 when it came out, because menswear suddenly has so much momentum behind it.

Cohn: Well— I have to say thank you for your kind words, but I think that the root of Today There Are No Gentlemen was a very simple idea, that people express themselves by their choice of clothing— that no piece of clothing is arbitrary, that it says something about you and how you want to be in the world. And that seems, now, an elementary thought— but when the book came out, it wasn’t. It made men very angry— “I just throw on whatever was in my wardrobe, and all this stuff about expressing myself is arty-farty rubbish,” and so on. So I got a lot of pushback, which is why it didn’t have a long life…but the other reason, of course, is because it’s very specific to England. So really, at that time, I’d have had to do a companion volume in America, and a companion volume elsewhere, and they’d have to publish it one by one by one…so it had a brief life, it hardly had a life at all, and then it disappeared…I think it’s the only one of my books that has had no reprints till now, the Japanese edition you’ve been talking about. It feels as if people are finally ready to talk about fashion at a non-trend level and focus on what fashion says.

Marx: You were writing about rock’n’roll, and music…where did the original idea come from for you to also write about fashion? Was that from the publisher, or did you yourself decide that you wanted to write about it?

Cohn: Well, I think it was decided over lunch, with my publisher, who’d also published Awopbopaloobop, and obviously had done well with that, so he was pretty receptive…my publisher, Tony Godwin, had said ‘Okay…have you got any more where that came from?’, meaning Awopbopaloobop.

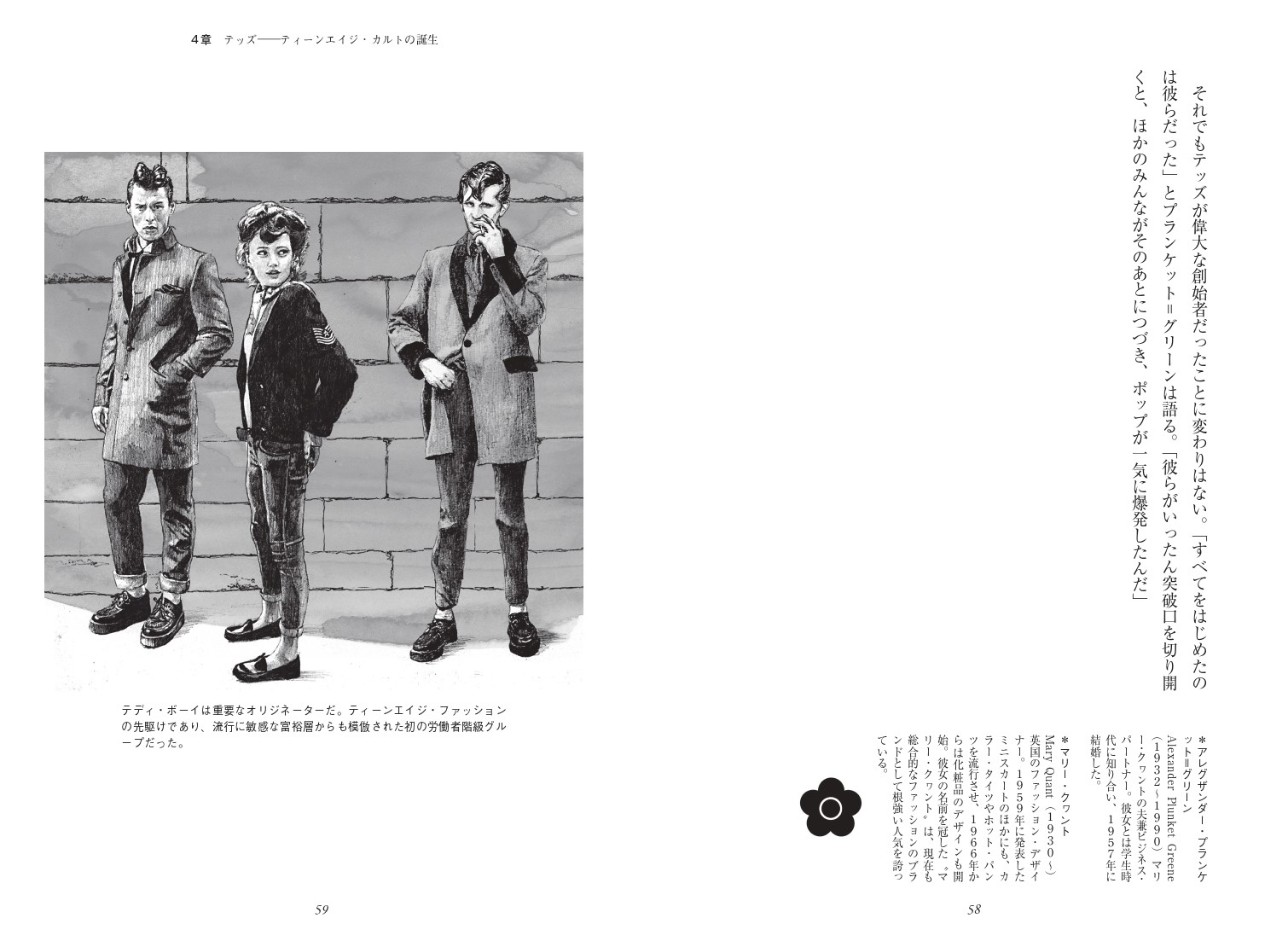

Marx: Today people talk about teddy boys, skinheads, mods, as iconic and respected subcultures. But obviously, at the time, they were widely loathed, right?

Cohn: Yes, absolutely.

Marx: How did readers at the time react to you taking them seriously as social movements? Because your book is not mocking them nor criticizing them. It treats them as legitimately expressing their feelings through clothing.

Cohn: Well, it was kind of my trademark, in a sense, because that’s what I always did. I mean, I went to the streets when writers weren’t going to the streets, they were going to the elite. I was saying this is where the energy is, this is where the reality is. And that’s what informed my rock book, it informed Gentlemen, and of course, later on, that’s exactly what informed Saturday Night Fever, which also got a lot of pushback…until the film came along, that is.

Marx: Certainly a lot of tension in your book [is in the idea] that British clothing was meant for “gentlemen.” In other words, fashion is an upper-class practice that trickles down to everyone else. In your book, you write about how working class youth were stealing those fashions directly and making them their own, or creating new fashions, almost like junior aristocrats. A lot of this parallels what Tom Wolfe was writing about American youth culture, and I wondered how you felt about his work at the time.

Cohn: Well, of course I was aware of Tom Wolfe…and I was never a fan of his. I didn’t like writing where the attention is meant to be on the writer, rather than on the subject. There’s a lot of grandstanding with Wolfe, a lot of look at me, I’m so clever, and the real story tended to get lost. He wrote, what was it, “The Noonday Underground” [on British mods], I knew those people, that club, and it didn’t have the kiss of reality at all to me. I felt here was a snooty guy, taking a day off being snooty, never getting below the surface. He wrote like a day tripper, where I didn’t have to go very far from my front door. This was my life. I wasn’t just there for the weekend.

Marx: That’s very interesting.

The waning appeal of ephemera

Cohn: It was my life, and then suddenly it wasn’t. In my late twenties, I suddenly lost interest in fashion.

— That was in the late ‘70s?

Cohn: Yeah, that was in the mid-70s. Suddenly there were a lot of other youngish male writers who started writing about “style.” And they referred to me as if I’d invented “style.” And I couldn’t respond to that…I didn’t invent “style” any more than I’d invented the “rock critic.” I just wrote about something that interested me.

Marx: I get that sense at the end of your book, because you talk a lot about how suddenly not being into fashion was the fashionable option. Were you talking about yourself?

Cohn: I think so, to a degree, yes. I think I was very attracted to ephemera— the idea that rock or fashion was simply a moment, here it was, and then, just like that, gone. And therefore, whether it was with rock or with fashion, the idea that somebody would open a boutique, make fabulous clothes, and forty years later, they’d still be in the same boutique, making replicas of the original styles, that was anathema to me. My thought was, you create something new, you revel in the moment, enjoy it to the max, and then you move on.

−− Nik, you have a great line in the book, about taste, where you mention something Donovan says, that he thinks of taste as “very boring and meaningless.” You write: “This was great ignorance on his part: taste is not an absolute but evolves constantly, and what is good taste in one age may be rotten in the next. During our time, it has been used as a synonym for orthodoxy and politeness but that’s a misuse. Good taste, if it can be defined, means whatever works in its own moment and certainly, in the sixties, white shirts and baggy grey suits weren’t it.”

Cohn: [laughs]

Marx: I think you’re chronicling a very important turning point for the concept of taste there. For a long time there was an authoritative idea that there is a good taste, and yes it shifts, but it shifts slowly. What you write about in the 1960s is that moment in which taste becomes detached from an upper-class establishment, and becomes much more protean, and really becomes what does work in the moment. Now that’s the world we live in, and [in the book] you’re capturing this change as it’s happening in real time.

Cohn: Hm…yes, I think that’s right. I think that one of the subtexts which, obviously, publishers really didn’t want me to go into to much, in 1971, was this curious thing— that you had the working class creating fashion, but they hadn’t really created it: they took it from gay culture. I’m just talking about England now. Almost everything important, everything that really changed the feel of things originated in gay culture, gay clubs. That’s where it was born. And then the working-class kids took it over. Many of them would be homophobic, but they still knew a great new look when they saw one.

Marx: On top of that, there is also the Jewish influence. In the U.S., many of the prominent clothing industry pioneers were Jewish: Ralph Lauren, J. Press, and all of these brands that are foundational for what American style is. Did you feel like you had a specific perspective on that going into it?

Cohn: You know, I didn’t really think about it at the time…I was too close-up, and it didn’t really resonate with me. And I didn’t identify particularly as Jewish…even though both my parents were Jewish, they didn’t give me any Jewish culture. In retrospect, looking back…of course it’s not only gay, it’s Jewish-gay.

Marx: And would you put Brian Epstein in this world as well?

Cohn: Yes, very much. There were exceptions, like Robert Stigwood, but that’s the base narrative. Because they were, in those days, outsiders, rebels, and so they could empathize with working-class rebellion and see how to market it. And of course, in many cases, they fell in love with everything they were helping to create.

Marx: In reading your chapters about the mod movement, I wasn’t under the impression that the pioneers were gay, but I’m guessing, because of the prejudices of the moment, I’m guessing you had to underplay the gay influence.

Cohn: I think so, yes. I don’t think it was compulsory to be gay, but when I look back on it…at the time I wrote the book, I didn’t categorize people in my mind as ‘he’s gay, he’s straight.’ Now, with perspective, I see that the change in mens’ fashion, the creation of Carnaby Street, the creation of King’s Road…many entrepreneurs were both Jewish and gay. Exception was John Stephen, who almost single-handedly made Carnaby Street the hub of teenage fashion.

*Continue to Part 2

Nik Cohn

Born in London in 1946, and raised in Derry, Ireland. Sometimes known as a “father of rock criticism.” The film Saturday Night Fever was based on an article Cohn wrote for New York Magazine in 1976. In 2020, Today There are No Gentlemen (DU Books), which details changes in mens’ clothes through the boutique owners, designers, and rock stars who revolutionized English fashion, was translated and reprinted for the first time in Japan. Other works from Cohn translated into Japanese include The Heart of the World (Kawade Shobo Shinsha).

David Marx

Born in Oklahoma in 1978 and raised in Florida, he graduated from Harvard University with a B.A. in Oriental Studies in 2001, and from Keio University with an M.A. in 2006. He has contributed articles on Japanese music, fashion, and art to The New Yorker and GQ among other publications. He is a founder and editor-in-chief of the web journal Neojaponisme. His book Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style, published in 2017, became a hit with six printings in Japan, an unprecedented number for a book focused on the history of clothes.

Twitter: @wdavidmarx