‘Genesis have always been slightly below the radar,” says keyboardist Tony Banks. “We’ve never been part of a current trend; we don’t tend to get awards; we’re just sort of … there. People that like us really like us, though, and that’s all we care about.”

“Below the radar” may be a strange way of describing a band who have sold more than 150m albums. But, then, Genesis have always been peculiarly self-effacing. From their early-70s, Peter Gabriel-fronted iteration, where they quickly ascended to the upper echelons of progressive rock with a combination of theatrical whimsy and fiendish technical complexity, to their slicker, poppier, staggeringly successful 80s years, they remain a wildly popular – yet pleasingly eccentric – proposition.

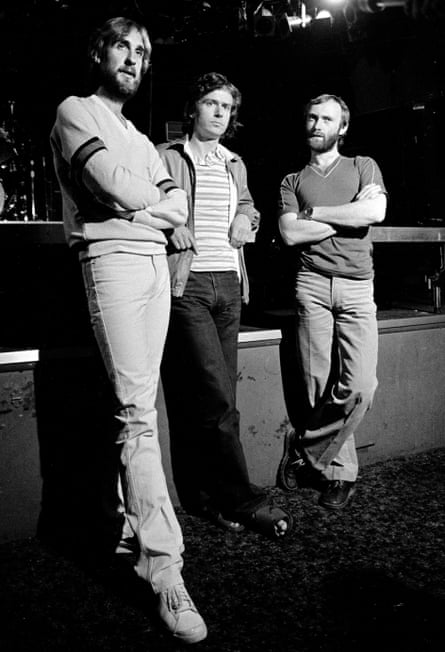

Rehearsing for the band’s The Last Domino? world tour (their first since 2007, and twice delayed by the pandemic), the band are in a warehouse studio in a London industrial estate. Amid black drapes and hundreds of flight cases, lights are set up for a BBC TV interview that is interrupted comically frequently by hammering and drilling from building works outside. After about half a dozen false starts, a bearded roadie is dispatched to “make it stop”. Beeb interview duly in the can, I am ushered into a side room to meet Banks, Phil Collins and guitarist-bassist Mike Rutherford.

Collins has suffered a well-documented period of extended ill health over the past few years: dislocated vertebrae led to nerve problems that have stopped him drumming, and he is diabetic. He is frail and seems slightly distracted, walks with the aid of a stick, but is in good spirits. Banks and Rutherford are self-deprecating and relaxed.

Formed at Charterhouse school in 1967 by Gabriel, Banks, Rutherford and guitarist Anthony Phillips, the band started out making fey acoustic pop, unrepresentative of what was to come. Their 1969 debut LP, From Genesis to Revelation, tanked (supposedly, copies often ended up in the religious section of record shops) and various lineup changes followed before the stronger second album, Trespass. Needing a drummer who could drive their increasingly complex material, the band found a young Collins, in 1971, along with virtuoso guitarist Steve Hackett, in time to record the bona fide prog classic album Nursery Cryme. Typified by the heavy 10-minute epic The Musical Box – a macabre tale involving croquet, decapitation and a haunting – Nursery Cryme had a keenly chiselled dynamic range and fantastical lyrics.

Subsequent albums such as Foxtrot, Selling England By the Pound and The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway positioned Genesis at the top of the progressive tree alongside the likes of Yes, King Crimson and Emerson, Lake & Palmer. By 1974, relations with Gabriel had become fraught. After he informed the band that he was leaving during the Lamb Lies Down on Broadway tour, Genesis auditioned more than 400 potential singers, with Collins taking on the arduous task of guiding them through the melodies. Eventually, it dawned on everyone that he had a better voice than the lot of them. Did he actually enjoy singing, though?

“I did enjoy it,” he explains. “I set out what I would do and what I wouldn’t do. I personally felt that some of the visuals, the costumes and so on, were getting in the way of the vocals.” Gabriel had variously dressed up as a flower, fox, bat and the fascinatingly pustular creation Slipperman. “I didn’t think I’d be very good at doing that theatrical stuff anyway. So I said: ‘Look, I can sing the songs, but anything else will be a bit of a question mark.’” Collins did get in on a bit of Gabrielian horseplay in the end. “I was on stage running around and talking to the audience … the only [costume] I did was Robbery, Assault and Battery. I put on a jacket and a hat and became the Artful Dodger.”

The first Collins-fronted LP – 1976’s A Trick of the Tail – was well received, while next, Wind & Wuthering, saw a conscious taming of some of Genesis’ more fantastical elements. More turbulence was on the cards, however, as Hackett left in 1977 to pursue a solo career. Collins, Rutherford and Banks recorded And Then There Were Three the following year.

Banks remains surprisingly sanguine about Hackett’s departure. “Mike suddenly had to play more lead guitar so there was a moment or two of getting that together.” He turns to Rutherford: “I think you did a good job, actually!” Collins pinpoints 1980’s Duke as “the more progressive change. And then [the 1981 LP] Abacab was where there was a really conscious change. But the comings and goings of the various musicians? It didn’t affect our trajectory as much as all that. After all, a large percentage of the group – us three – was the same. And we were all writers.”

But how, exactly, did Genesis move from being titans of prog – famed for 20-minute epics, lofty concept suites and bizarre costume changes – to stadium-filling 80s everyman popsters? The band remain adamant that the punk and new wave explosion of the late 70s had next to no impact on them, despite the fact that prog was – almost overnight, and with serious critical venom – deemed passé.

“The thing was, I didn’t like a lot of the bands that they didn’t like, too,” says Collins. “I always saw us as slightly separate from all of that. And when punk happened, we were away an awful lot – three American tours and three European tours. I used to get Melody Maker and all those papers every single week, but I wasn’t getting them any more. The short periods that I was at home, I don’t think I heard a single Clash record or Damned record. It just passed me by.”

“I always felt we were lucky to be the last ones left standing,” adds Banks. “Our competitors – people like Yes and ELP – had faded by that point. So we were the last of that prog bastion. We actually had our first hit record – Follow You Follow Me – during the height of punk. It kind carried us through that time.

“It’s funny, I remember walking down Wardour Street one day and saw this guy in full punk kit: ears pieced, pins, leather jacket. He ran up to me and said: ‘Tony Banks! I really need your autograph!’ And he pulls out this copy of Pretty Vacant for me to sign. It actually showed what I’d always known: that people have multiple tastes, people aren’t stuck in a rut. They like a bit of this and a bit of that.”

Duke and Abacab were markedly different – the trio entered the studio without any pre-written material, improvising in a spirit of equal collaboration. The former was punchier and rockier than anything that had come before; the latter colder and synth-led. Both were – by comparison to their 70s material – polished to a fine sheen. They also, however, became overshadowed by the profile of Collins who had – by 1981 and the release of his album Face Value – embarked on a phenomenally successful solo career (Banks and Rutherford also released significantly more leftfield solo work around this time). Immediately suited to the transatlantic AOR FM dial, the Collins solo sound was slick, emotive, personal – a different animal to Genesis, with more overt R&B and pop influences.

“Phil was on a roll in the 1980s,” Rutherford says. “Everything that he touched came good – everything. His first solo album went ballistic just when we were about to release Duke – it was good timing!”

“It helped us,” agrees Banks. “Most band members start solo careers because they aren’t happy with the band or they’re frustrated. We did it for variety and change. It made us look forward to coming back to Genesis. We’d come in with no idea and just see what happened. The drum machine might come on; I’d play a riff. We’d improvise.” Citing Land of Confusion from 1986’s Invisible Touch, he says: “I was amazed by how concise we could be.”

Invisible Touch remains Genesis’ biggest album, the title track reaching No 1 in the US. It is this iteration of Genesis that became a byword for slickly efficient pop, far removed from the Gabriel era. Genesis gained a younger, MTV-generation audience, many of whom were completely unaware of the band’s leftfield past. Bret Easton Ellis ended up including an entire chapter dedicated to the band – and the solo works of Collins – in American Psycho, with Patrick Bateman dissecting them in disturbingly forensic detail, making this era of Genesis a byword for 80s excess (needless to say, Bateman dislikes the Gabriel songs).

“Everything just kept getting bigger,” says Collins. “It just caught fire, and my solo records were doing very well in America, too – it all converged.”

“I don’t think we felt much pressure,” adds Banks. “We were confident. You have to remember: it had been such a slow trajectory for Genesis. It was 10 years before we even had anything played on radio!”

But what about pressure today? In the aforementioned BBC interview, Collins mentioned, as he frequently has in the past, his inability to play the drums; his 20-year-old son Nic will play them on the forthcoming tour. But what, I wonder, about singing? A three-hour arena show is a serious physical undertaking – what does he do to stay vocally fit?

“I don’t do anything at all,” says Collins, as Banks and Rutherford look on, uneasy for the first time. “I don’t practise singing at home, not at all. Rehearsing is the practice. These guys are always having a go at me for not, but I have to do it this way. Of course, my health does change things, doing the show seated changes things. But I actually found on my recent solo tours, it didn’t get in the way; the audience were still listening and responding. It’s not the way I would have written it, but it’s the way that it is.

“Playing with Nic, though? That’s been easy,” he continues. “He started playing with me when he was 16. If I feel that he should concentrate on something to make it better I’ll mention it and he’ll come back the next day and he will have done it. He doesn’t need constant nudging; he pulls it together with remarkable ease. I used to take him and his younger brother to school in the car, and they’d put on a Genesis live CD, so he’s been around it for a long time. I’d just let him play down in the playroom and I’d hear his progress; he’s been playing well for as long as I can remember. I’ve got videos of him from when he was five years old just standing and playing. He pretty much taught himself – occasionally I’d nudge him in the right directions.”

As The Last Domino? is likely to be the final major Genesis tour, do the three feel a sense of nervous energy? “A little,” says Banks. “But I always feel like a bit of spectator up there. It’s not real, in a way … You just do it. It’s gratifying to hear the songs you’ve written getting a great response but I’ve never …” He pauses. “The fame thing doesn’t interest me at all.”

“We’ve been doing this for 50 years now,” concludes Rutherford, slightly wistfully. “It’s just …” and he pauses, too. “It’s what we do.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion