By the end of the 80s, it seemed certain that Metallica would be the biggest metal band in the world. Their 1988 album, … And Justice for All, had been in the US chart for a year and a half. Their first music video, One, had finally earned them MTV airplay, blasting their intricately crafted savagery through every TV set in the US. Their Damaged Justice tour had packed arenas across the US and Europe.

They seized their moment with the Black Album, as their self-titled next LP became known. Released 30 years ago this month, no metal album since has matched its impact; every parameter was reset for what such belligerent music could achieve. It went 16 times platinum in the US and has spent 622 weeks (and counting) in the US album chart. Its third single, the swelling Nothing Else Matters, passed 1bn YouTube views last month. The band are commemorating the record’s 30th anniversary by releasing a 52-track covers album, The Metallica Blacklist, with stars as giant and eclectic as Miley Cyrus, Elton John, Phoebe Bridgers and Biffy Clyro giving their takes on the album’s tracks.

“Thirty years of the Black Album, it’s a pretty big year,” says Metallica’s singer, guitarist and co-founder, James Hetfield, rather drily – by his own admission, they are a band not usually given to looking back. “We’re overachievers and we’re perfectionists. We think outside the box and we try to be the first at things. There’s no nostalgia driving this band; we used to be very fearful of it.”

True to that spirit, Metallica defined a new subgenre – thrash metal – with their 1983 debut album, Kill ’Em All. The searing sound of hard rock virtuosity grinding with punk, it was a counterattack against hair metal’s domination of the scene. The next year’s follow-up, Ride the Lightning, controversially introduced acoustic guitars and bass solos, before 1986’s Master of Puppets became an underground smash, incorporating never-before-heard song structures and eight-minute-long instrumentals.

The subsequent Justice was an even bolder test of metal’s limits. For up to 10 minutes apiece, its monolithic tracks marched between countless time signatures. “The band’s breakneck tempos and staggering chops would impress even the most elitist jazz-fusion aficionado,” wrote the Rolling Stone critic Michael Azerrad in his review.

“There was a lot of ego and showing off on Justice,” says Hetfield. “Going out and playing Justice live, the songs were eight, nine, 10 minutes long.” The Black Album was the polar opposite. The previous albums had vibrant, politicised paintings on their covers; this one was jet black, broken only by an embossed image of a snake, while the songs were stripped-back rockers. No 10-minute suites, no wacky rhythms – just stomping, catchy, heavy metal.

This music became so prominent in global pop culture that Tomi Owó, the Nigerian R&B singer whose rendition of Through the Never appears on The Metallica Blacklist, remembers “seeing Metallica without even listening to the music. When I was in high school, my friends would come back from their summer holidays with Metallica shirts.”

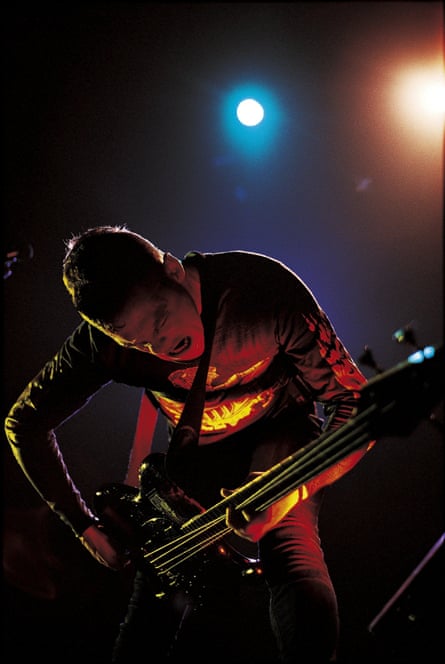

“It was an amazing time that could never happen again,” summarises Jason Newsted, the band’s bassist from 1986 to 2001 (he was replaced by Robert Trujillo). “Demographically, the way the world lined up – the amount of people that were 12 to 22 years old, before the internet – it was such an important movement in time. We played 50 countries and they were all the same, as far as the togetherness and commitment to being a part of something so much bigger than you.”

For Hetfield and Kirk Hammett, Metallica’s lead guitarist, the first aim when writing the Black Album was to sprint as far away as possible from Justice’s incessant technicality. “One of the things that we all agreed upon was simpler, bouncier riffs,” remembers Hammett. For Lars Ulrich, the drummer, the reinvention meshed perfectly with his mission to invade as many ears as possible. “I’ve heard a story about them going to a strip club,” says Ben Thatcher, the drummer in Royal Blood. The garage rockers cover Sad But True on The Metallica Blacklist and Thatcher has long been friends with Ulrich. “A Mötley Crüe song came on and Lars went: ‘Man, why doesn’t a Metallica song come on when we’re in these places?!’”

Hammett corroborates: “That’s true, but there’s more to that conversation, too. He’d always think: ‘Those drums sound really good!’”

Already exhausted by their involuted songs, Metallica had jammed the riff of Sad But True – the Black Album’s slowest, heaviest cut – on the Damaged Justice tour. However, songwriting didn’t start properly until they got home in late 1989; much free time on the road had been occupied by what Newsted euphemistically calls “powders”.

“We discovered cocaine years before, but we brought it to new heights on that tour,” Hammett says. “We’ve always dialled it back while we’ve had responsibilities writing, rehearsing and recording an album. The way we work is every day for 15 hours a day. There’s no time for that sort of thing!”

By late summer 1990, six new songs were all but finished and Hetfield and Ulrich met in the drummer’s basement to record demos. Alongside Sad But True were Holier Than Thou, The Unforgiven, Wherever I May Roam, a lyricless Enter Sandman and Nothing Else Matters – a smitten ballad Hetfield never wanted the world to hear.

“It was something I’d been messing with after shows, when it was dark and the crowds were gone,” he says. “It was like: ‘The rest of the guys are gonna laugh at this. Maybe it’s not Metallica; maybe it’s too vulnerable.’”

In a seemingly out-of-character move for the fire-spewing “Papa Het”, the track was a love letter to his then girlfriend, written while homesick on tour. He even conceived its opening – four open guitar strings – while on the phone with her. “I was probably bored of the conversation,” he laughs. It was only after nudging from his bandmates that the song was shared: “That was the beginning of: ‘It’s OK.’ Any feeling you experience as a human, you should be able to write and talk about it.”

Today, decades after the couple’s breakup, Nothing Else Matters has become an ode to long-distance relationships. “It’s written vaguely enough – ‘So close no matter how far’ – that it can mean anything,” Hetfield says. “It’s a wedding song and the Hells Angels have used it in their documentaries.”

Hammett, Ulrich and Newsted didn’t share Hetfield’s feelings of romantic longing; between the releases of Justice and the Black Album, all three got divorced. The guitarist and drummer each got married in 1987, before splitting from their wives after the Damaged Justice tour. The bassist wed in 1989, only for the union to be annulled after a few months.

“There were a lot of factors that contributed to my divorce, not least of all my own behaviour,” Hammett says. “But there was also being away for 12 weeks at a time in Europe and then going straight into an American tour with only eight days off in between. It wreaked havoc on that relationship.”

Hammett says marital strife had brought the trio closer together before Metallica entered One on One Recording (now 17 Hertz Studio) in Los Angeles in October 1990. Yet, over the eight-month-long sessions, cracks emerged within the unit. Ulrich’s intensely methodical approach got under the skin of his peers; as seen in the 1992 documentary A Year and a Half in the Life of Metallica, he demanded Hetfield sing during one of his drum takes, despite the frontman resisting due to vocal troubles.

Newsted – still accustomed to the faster recording style of his prior band, Flotsam and Jetsam – also clashed with his hyperperfectionist comrade. He says: “I think you’ve seen a lot of stuff in the film as far as Lars’s behaviours: insisting on one more take and changing the snare head every take. Those kinds of things were new to me. On the 60th take of Nothing Else Matters, it’s like: ‘Come on, man! What the fuck, dude?’ I love Lars to pieces, but I don’t see why we have to do it 70 times. Can we just fucking play the music?”

Fighting to maintain order was the producer Bob Rock. Metallica hired him after hearing his work with Mötley Crüe and on the Cult’s Sonic Temple, knowing he could bring the low-end oomph that the Black Album needed. But as much as they admired Rock for overseeing what Hammett calls “a bunch of really great-sounding records”, his wheelhouse was in hair – the very subgenre Metallica seethed over during their ascension in the San Francisco Bay Area.

“He came from ‘the other side’,” says Hammett. “He was working for bands that were really radio-oriented, like Bon Jovi, Mötley Crüe, Loverboy and Aerosmith. We were that heavy metal band that just wanted to be a heavy metal band. We were worried about suggestions coming from Bob that we might not agree with, because they weren’t part of our own moral code.”

As a result, arguments frequently raged inside the studio, with tensions arising over everything from song arrangements to mixing. According to Newsted, Hetfield “would burn a hole in [Rock] with his eyes” whenever he suggested a musical change. Later, the producer butted heads with Ulrich over what the lead single should be; while Rock favoured Holier Than Thou, the drummer insisted it be Enter Sandman, a creeping anthem inspired by grunge upstarts such as Soundgarden. The production proved so arduous that Rock stated in a 2011 MusicRadar interview: “I told the guys when we were done that I’d never work with them again.” (In fact, he went on to co-produce three more Metallica studio albums.)

Meanwhile, the discourse among fans outside was no less acrimonious. News of Rock’s recruitment triggered tirades about Metallica “selling out”; Enter Sandman only exacerbated the outrage by cracking the Top 10 in numerous countries. Newsted’s reply to the dejected has long been the same. As he said in 1998: “Yes, we sell out – every seat in the house, every time we play, anywhere we play.”

“I think a lot of their original fanbase felt betrayed,” says Eamon Sandwith, the frontman of the Australian punks the Chats, who contribute Holier Than Thou to The Metallica Blacklist. “But, for kids like me that had never heard a metal band before, we had Enter Sandman on the TV.”

For The Metallica Blacklist, Hetfield predicts a legacy similar to that of the gamechanger that inspired it: a broadening of Metallica’s horizons, albeit one that won’t pass without a backlash. “We cast the net as wide as possible: to rock, alternative, country, bluegrass and rap,” he says. “I know there’s a lot of Metallica fans out there who are pretty concerned about that. Don’t worry; Metallica is Metallica. Somebody covering our song isn’t going to change us.”

If anything, the covers album is a reignition. A fortnight after its release, the band are starting a tour for the first time in two years (all dates between September 2019 and the Covid pandemic were cancelled due to Hetfield re-entering rehab for alcohol addiction). Hammett promises new music will follow: “Over the last year and a half, we’ve been consistently working. The fruits of all that will be heard sooner or later.”

As for Newsted, who stepped down in January 2001 after Hetfield voiced opposition to him joining other bands during Metallica’s downtime, he has since played for Ozzy Osbourne and the progressive thrashers Voivod. He also worked on a solo project from 2012 to 2014; its EP, album and tour were funded by Black Album royalties. Today, he leads the Chophouse Band, an Americana outfit for which he composed 50 songs during the pandemic.

With “a lot of water under the bridge”, Newsted considers himself “better friends with the Metallica guys now than I probably ever was. Obviously [leaving Metallica] was the right thing to do, because they’re still fucking crushing and I’m here smiling at you.”

“We’re still explorers,” says Hetfield. “A project like the Blacklist is proof of that. Someone once told me: ‘The rear-view mirror is smaller than the windshield for a reason.’”