Editor's Note: In this story, we use the tribe names preferred by the Séliš-Q’lispé Culture Committee, a governmental body established by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in the 1970s. The spelling of Séliš you see here is used by the Culture Committee in ongoing projects and publications related to language, history, and ethnogeography. When citing or quoting individuals from other tribes, we defer to them. Some people prefer Indigenous names (for example, Diné, Amskapi Pikuni, or Apsáalooke). Some people prefer anglicized ones (Navajo, Blackfeet, or Crow).

The boy and the old woman let the silence gather. He was used to her talking with her hands and cracking jokes over French toast. Now she was quiet and still, a hospital gown hanging off her shoulders. It was Wednesday, March 8, 2017. From the second-story window at Providence St. Patrick Hospital, in Missoula, Montana, Will Mesteth Jr. could see low clouds clinging to the timbered hillsides. Soon it would snow. He looked down to the parking lot. The bus was due any minute. When his t̓úpyeʔ eventually spoke, she told him to go, that she would be fine, the same thing he had heard his whole life: Don’t worry ’bout me. She always said she was tough enough to handle anything the world could offer, and he had no reason to doubt her. But there was something different about her stillness, and the space between her words. He felt weird. Frozen, almost.

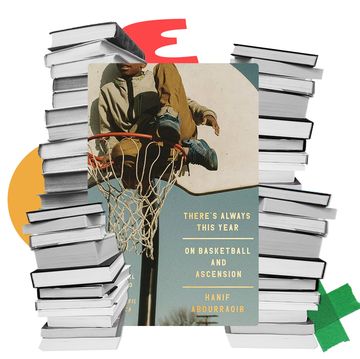

In front of Sophie Cullooyah Stasso Haynes were two versions of her great-grandson. On the wall of her hospital room hung a poster of him in the air, moving toward a basketball rim in his red-and-white Arlee Warriors jersey, mouth agape, the memorial tattoo for his sínceʔ—his brother Yona—visible on his muscled left shoulder. Seated in front of the image was the child she raised, William Mesteth Jr. He was sixteen now, about five foot nine and solidly built, with the first wisps of reddish brown hair sticking out of his chin and the last of his baby fat clinging to his cheeks. His hair hung to his shoulders. She called him Willie.

He was a quiet kid. In class he didn’t say anything; girls thought he was shy, and teachers wondered what was wrong. His mother, Chasity, said he was just quiet. His father, a tribal policeman whose name he took, worried his son had trained himself to disappear. With Sophie it was different. A Séliš elder, she had raised him from birth. Will and his t̓úpyeʔ talked about everything: hunting, the past, trucks, his siblings, his dreams. He called her “the most kindhearted person you’ll ever meet.” Other family members saw a different side of her. “Mean,” “strict,” and “o’nery”— those were the words more often used.

Will grew up on seventy acres of the Jocko River Valley in Arlee, Montana, near the southern end of the Flathead Indian Reservation, home to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. The property was a tribal allotment with horse pastures, a neat family cemetery, and multiple homes. Sophie lived near the entrance, in a warm wooden house where she raised Will. Chasity resided just up the way, in a newer modular home. Beyond that were places belonging to Sharon, Chasity’s mother and Will’s grandmother, and various aunties and uncles. Everyone just called it Haynesville, and there was little doubt as to who was in charge. Chasity was a teenage mother, so when Will arrived, Sophie took him in. She spoiled him, giving him Cream of Wheat, pancakes, or burgers whenever he wanted. It was as though his arrival had given rise to some soft new hope. Later on, when he heard thumps in the house, he rushed to Sophie, knowing she had fallen. He helped her up, then she got back to whatever she had been doing. “Pretty tough woman,” he said. Beeps and hushed voices filled the hospital. Along with Will’s yayá Sharon and aunties, Chasity sat in a nearby waiting room. Séliš and Navajo, she was thirty-two now, a working single mother of six with long hair, well-kept nails, and a cluster of tattooed stars descending from behind one ear. She wouldn’t interrupt. “When he comes,” said Chasity, “we let them have their time.” But the women in the waiting room all wanted Will to leave when the bus arrived to drive him to the state tournament, which was to take place over the next three days. In the past year, he had transformed from a failing student and potential dropout to a star shooting guard on a dominant team. People now put him on posters and talked about him in barbershops.

Down below, Broadway was busy, cars kicking slush to the side of the road. Beyond it, the Clark Fork River carried ice toward Idaho. In March, western Montana combines the cold of the Northern Rockies with the moisture of the Pacific Northwest. It’s a season of low skies, heavy snow, perilous roads, and radio announcements imploring basketball fans to drive safely. In Montana, March means frenzied travel over icy passes to high school tournaments. The bus was coming to pick up Will for the most consequential of them all.

In rural Montana, on the weekend of the state tournament, small towns evacuate, their residents filling arenas designed for rock bands and college teams. The Warriors competed in Class C, the division representing the state’s smallest schools, where basketball occupies emotional terrain somewhere between escape and religion. Arlee, Montana, has an estimated population of 641, if you choose to believe the US Census, which no one locally does. That weekend, Will was scheduled to play in front of a crowd approximately ten times that size in Bozeman, two hundred miles to the southeast. Despite years of high expectations, and despite the presence of one of the state’s most dynamic players, Will’s cousin Phillip Malatare, a Séliš and Cree point guard, the Arlee Warriors had never won the state championship. Will’s addition had turned the team into something formidable, a pressing, blitzing group that outscored opponents in dizzying runs. Will’s sudden ascendance brought his family intense pride. Chasity filmed each contest on a smartphone, while Will’s father, Big Will, took his place by a large drum alongside the boy’s grandfather and uncles, singing before the team took the court.

Twenty-five miles north of Missoula, in Arlee, people made last-minute preparations, painting truck windows with the names of players and trying to book hotel rooms in Bozeman for the three-day tournament. For the Arlee Warriors, the pride of the Flathead Indian Reservation, state was not just a matter of boyish fun. The previous year, they had made it to the championship but lost. They’d entered this season hoping to avenge that disappointment, but by now, it had taken on an entirely different significance. To the Warriors’ coach, Zanen Pitts, a thirty-one-year-old rancher and a first descendant of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, the trip meant something so great it was almost ineffable. “This is your opportunity to relieve the pain,” he said, of the boys. “This is your guys’s calling.”

Two weeks earlier, on Wednesday, February 22, word of a death had rippled through the Jocko Valley. The deceased, Roberta Roullier Haynes, was an aunt of Will’s and a foster mother, with a kind smile and long auburn hair, who often organized community events. She and her husband, TJ, a tribal policeman, were close with many of the Warriors, and the boys grew up playing in their yard. The cause of death was suicide, but Will did not know that at first. His family initially kept it quiet. It was not the first such tragedy to strike Arlee that season. Since the fall, the community had been in the midst of what public health officials call a suicide cluster, a darkness that spasmodically took its toll. Roberta’s passing had been a jolt to the heart of the team. “She was family,” Will said. He had wondered if he should skip the next games, the divisional tournament preceding state, to be with his family. His cousin Phil, the Warriors’ electric point guard, was particularly close to Roberta; to him, she was “like an auntie.” When Phil’s parents shared the news, he padded downstairs in his socked feet and shut the door to his room, closing himself in among the basketball jerseys and tournament brackets. But that same afternoon, Phil was at the gym, preparing for all that was asked of him. For him, to miss a practice would have been impossible. “It was time to get down,” he said.

That weekend, the Warriors had blitzed their opponents. Over a three-game span, Will scored 49 points, Phil, 67. Then, on the Monday following the divisional tournament, and less than two weeks before state, there followed another suicide, the deceased an uncle of a talented sophomore on the team named Lane Johnson. A wiry, shy Séliš kid who was all eyelashes, Lane missed practice that week. At practice, Zanen and the boys started calling out the names of those they were playing for. It was a wild, building feeling—“like cooking with jet fuel,” according to a senior named Ivory Brien, who was Amskapi Pikuni (Blackfeet) and Apsáalooke (Crow). “We’re not just playing for ourselves, we’re playing for this community. And specific members of the community.” Phil’s father, John Malatare, a Séliš and Cree wildland firefighter, told his son and nephews that when they played, they allowed people to briefly forget their worries. Lane Johnson returned to practice on Friday, March 3, to ensure his eligibility for state. “I knew,” he said of his uncle, “he wouldn’t want me to miss out.”

Only Will’s attendance was unassured. Just a few days before the team was to leave for Bozeman, Sophie suddenly lost the ability to form words. She was rushed to the hospital, where it was determined she’d suffered a mild stroke. Will disappeared from both the school and the team, planting himself in the recliner next to her hospital bed. Coach Pitts brought the poster of Will to cheer Sophie up. He assured Will that his t̓úpyeʔ would want him to play, as did Chasity, his yayá Sharon, his aunties, and Big Will. Will loved and trusted them. But they were not in the hospital room, just as they had not been there on the summer mornings when Will learned to shoot.

Back before anyone put Will on posters, Sophie drove him north from Haynesville on US 93. They’d pass through Arlee and go to the Bison Inn Cafe, at the head of Ravalli Curves, or farther up the hill to Old Timer Cafe in St. Ignatius, at the foot of the whitecapped Mission Mountains. They’d order French toast—he with sausage, she with bacon. They’d head back south toward Arlee in her white Buick, the Missions receding behind them, the Jocko River and the railroad off to the right. A little farther south and they’d emerge into the Jocko Valley, Schall Flats spreading beneath tawny hills. Out to the west, near the river and the railroad, was his grandpa Allen and grandma Kelly’s house. And in front of them, at the foot of the valley, was the place where the timber on a mountainside opened to reveal the shape of a heart. Not a Valentine’s heart but the kind that pumps.

They would find a court. Maybe the one the boys called the Battlefield, by the junior high, or the Lyles courts on Pow Wow Road, past the community center. Sophie sat in the car while Will hopped out with a ball and walked onto the blacktop underneath backboards that read, “In memory of Thomas Lyles,” honoring a ballplayer who passed away young. Will curled his little body together, gathering energy, then flung himself upward, snapping his left wrist. The ball rose toward the rim. Most of the time it clanged off and he ran to retrieve it. But sometimes it ripped the net. Will imagined doing that at the state tournament to the sound of a thousand voices.

That day had now arrived, but he wasn’t sure he could go. The prospect of something happening to Sophie in his absence caused a discomfort that was almost physical. Down below, he saw the bus pull into the parking lot. The boys rode the silver travel rig with dual rear tires and, on the side, a spear piercing the word Arlee. The windows were painted with their names: Malatare, Bolen, Schall, Fisher. And he could see his name, too: Mesteth #3. He wanted to go with them. But he also kind of didn’t. The doubt that filled him was fresh and strange. Gray light filtered through the room, and Sophie smiled with arcing eyes. “I’ll be there,” she said. “I’ll be there.” That settled the matter. Will hugged her and walked to the bus. “My gramma’d never lie to me,” he said.

Three nights later, on Saturday, March 11, he looked up into the darkness and felt the eyes. Cameras lined the floor of Bozeman’s Brick Breeden Fieldhouse; above them, a human galaxy in red-and-white shirts extended to the top of the gym. Half of Flathead Nation, it seemed, had made the three hour-plus commute. A dapper former Tribal Councilman held a homemade scorecard, as had been his practice since the 1980s. Nearly all of the members of the girls’ basketball team, the Scarlets, were in attendance. Chasity sat in the second deck with her five younger children, one of them wearing face paint on his forehead that read, simply, Will. And in front of them, in the handicapped section, as promised, sat Sophie Haynes.

“Ladies and gennnnnnnntlemen!” boomed the announcer. “We are Montana Class C! We are one hundred and three schools strong! And this, this is our 2016–2017 Montana boys basketball state chhhhhhham-pionshhhhhhhhip!”

The fans supporting their opponent, the Manhattan Christian Eagles, had a shorter commute, one of about twenty minutes. Manhattan Christian was a private school affiliated with the Christian Reformed Church in Churchill, an unincorporated community just twenty miles from Bozeman. The area was settled by Dutch farmers in the late nineteenth century, and some players had names that reflected that history. But the surrounding region was quickly changing, with out-of-state wealth coming for low taxes, a burgeoning tech industry in Bozeman, and Montana’s natural splendor. The man with the microphone introduced Manhattan Christian first. Then he said the word Arlee. The sound was strange, a live thing rumbling from the court to the top row. Will felt as if he had occupied someone else’s body. He took in the vastness of the crowd and stepped onto the floor.

After promising Will she’d make it to the tournament, Sophie’s energy surged and her speech soon followed. On Thursday, March 9, she had surprised everyone with her strength at physical therapy. Chasity was shocked. She packed up her car and Will’s five younger siblings and headed to Bozeman for the tournament’s first game. There Arlee beat Plenty Coups, a team named for the great Crow chief. Phil’s stat line looked like a typo: 32 points, 15 rebounds, 9 assists, 6 steals. “Malatare was everywhere—shifting, gliding, leaping, lurking, shaking and baking,” boomed the Billings Gazette. On Friday morning, before the state semifinal, the doctors said Sophie was free to leave. One of Will’s aunties planned to drive her home. But Sophie announced that she wanted to go watch some basketball. A nurse who saw the images of Will said he was handsome. Sophie said, “I know.” A few hours later, she rolled into the gym in Bozeman wearing black slacks, a pink fleece, and a pin bearing Will’s likeness. He was not even a little surprised to see her. Then he poured in 28 points, firing shots from absurd distances and sending Arlee to the championship.

That night, Zanen Pitts, the Warriors’ coach, sat in his hotel room, stewing as though preparing to enter a fight. Zanen had a shock of reddish-blond hair, ruddy cheeks, cutting blue eyes, and seemingly boundless energy. He had grown up with a painful understanding that his family had yet to win on the state’s largest stage. He called it “the Pitts curse.” His mom, Crystal, had come in second while coaching track at Ronan High School. His brother, an all-state guard, had scored 35 points in the state championship in 2002, but lost. And before that came the defeat that Zanen remembered most.

In 1995, Terry Pitts, Zanen’s father, an enrolled tribal member, had coached the Arlee Warriors to the state tournament. Zanen was nine. He remembered walking into an arena in Great Falls and hearing a noise he thought would cleave his chest in two. He remembered the astounding feeling following a victory in the semifinal, against Lodge Grass, out of Crow Nation; he remembered being so happy he didn’t care when one of the Warriors gave him an atomic wedgie. His big brother, Zachary, spent that weekend alongside their buddy Thomas Lyles. Smart beyond his years, Tom was a thoughtful poet in school. He also loved basketball, knew every set. That weekend he introduced Zachary to a chant: “Nuts and bolts, nuts and bolts, we got screwed!” Zachary loved it. “Nuts and bolts!”

In the championship, Arlee had lost to Fairfield, a team from across the Rockies. Arlee Schools treated it like a success, with a motorcade leading the team bus home. In public, Terry said the right things: the boys had given it their all and learned about teamwork. But back at the Pitts ranch, there were long, long silences. Nothing was worse than second place.

Zanen now had a chance to redeem that loss. He knew what to expect from his opponent, Manhattan Christian. Their coach, Jeff Bellach, ran a motion offense, baseline screens, and plays designed to get the ball to towering post players or to create space for his son, a slashing sophomore. It was methodical and disciplined and utilized size: two of the Eagles starters stood six-foot-four or taller. Both of those players had transferred into the school. Arlee’s tallest starter was Phil, generously listed at six feet. Zanen ran few offensive plays, instead relying on elaborate presses to force turnovers. The defensive rotations were fast and coordinated, requiring a deep understanding between players and the ability to read passing lanes. A cousin of Phil’s named Tyler Tanner (Séliš) anchored it, calling out rotations; Phil, Will, and a sophomore named Greg Whitesell (Diné/ Lakota), the son of Arlee Schools’ superintendent, brought speed. The defense slowly wore the opponent down until the boys unleashed, leaving the other team gasping for air and the scoreboard lopsided. Zanen suspected that Bellach would use a zone defense to slow the pace, force the boys to attempt long shots, and stifle Phil’s acrobatic drives. On offense, the Eagles would likely try to attack Phil, hoping to get him in foul trouble and force Zanen to ease off on defense. Arlee had lost just three games in the previous two seasons. During each of them, Phil had fouled out. “If you get in foul trouble and they get in zone, we will not win,” Zanen said. He kept repeating two words to his wife, Kendra, that night: “unfinished business.”

His promise to his family hovered in his mind, as did the date. The championship fell on March 11—the anniversary of Thomas Lyles’s death. Zanen always remembered the way Tom had supported him as a young basketball player. He remembered telling Tom, as a teenager, that he’d one day marry Kendra. He remembered where he was when he heard about the accident that took Tom—on a bus to a college basketball tournament. With crackling grief setting in, he’d wanted to come right home. But someone had told him, then, that Tom would have wanted him to play. So he did. For Zanen, the basketball court was almost sacred. He thought about all the community had been through in recent weeks, and the names they called out in practice. He had unfinished business.

In the seconds before the Warriors took the court, the boys hopped around in the tunnel. Ivory thought about his job. He had to box out and take a charge. Strange butterflies filled him. He rushed off and vomited. The noise thundered. Greg tuned it out, a trick he’d learned from his father, David, the superintendent. Then he let it back in. Before the game, John Malatare had told his son and nephews, Tyler Tanner and Alex Moran (Séliš/ Cree), that this was the moment they’d been preparing for since age six.

Phil, Alex, and Ty had grown up playing together, and Alex’s mother, John’s sister Lynette, had told the boys that they would one day win state together.

From his seat, David Whitesell tried to quiet the worries that lurked in the back of his mind. Whitesell was a first descendant of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and a career educator. He knew that suicide is unfortunately common in Montana, and more prevalent still within Indigenous communities. In 2016, Montana had the nation’s highest suicide rate. Native youth were by far its most vulnerable demographic. In the event of a loss, he planned to increase counseling resources at the school. “It’s a lot to place on the shoulders of a bunch of adolescent boys,” he said. But he also wore his son’s jersey on his back that night. The superintendent recognized basketball’s complex effect, the pride and pressure it brought. “I see both sides of it,” he once said. “I love it.”

The crowd was simply huge, nearly filling the Brick Breeden Fieldhouse. That same weekend, in Great Falls, two hundred miles north, the Class A boys’ tournament brought in $57,000 in ticket sales. The boys’ Class C tournament brought in $106,000. At center court, Tyler Tanner lined up for the opening tip-off against a six-foot-five boy. Phil raised his arms, urging the crowd on. The ref threw the ball up, and despite the height differential, Arlee corralled the opening tip. Alex came down with it and kicked it to Phil, who made a move everyone knew was coming but few could stop: he crossed over, then quickly spun. But his shot clanged out of the basket, and Manhattan Christian pushed the ball to Caleb Bellach, the coach’s son, an athletic six-foot-three kid one year younger than Phil. He drove and Phil tried to close for a block. He fouled Caleb, who muscled the ball into the hoop. This was Zanen’s worst fear: Phil receiving his first foul just seconds into the game. Caleb missed the free throw, long. One of Manhattan Christian’s tall forwards came down with the rebound and flipped it in. It was 4–0. Phil drove and passed to Greg, who saw an opening, split a double-team, then shot a right-handed floater. It bounced off the front rim. Manhattan Christian grabbed the rebound. Caleb Bellach, on the wing, drove, took off, and leaped under the basket, laying the ball in. Manhattan Christian was up 6–0. Zanen liked to think of himself as a master of mind games. He was often calm during tense moments. Now, though, he thought, We’re going to lose this game. He called time-out and came undone.

Ty scored out of the time-out, showing up as he always did when it mattered most, and Arlee started to trap. Greg stole the ball and kicked it to Will, who in one motion dropped it to Phil, streaking up the court for a layup. It was now a close game, but Manhattan Christian’s size kept them on top for the first half. Early in the third quarter, Arlee trailed, 37–32. Then Phil saw something. As one of Manhattan Christian’s tall players grabbed a rebound, Phil’s eyebrows arched. He reached in and seized the ball. The other kid easily outweighed him, but Phil ripped it away and scored. Back on defense, Phil collapsed to the middle of the floor to stop Caleb Bellach’s drive. Caleb whipped the ball to the corner, where a tall, thin wing player named Parker Dyksterhouse caught the pass and released a three-pointer. But as he did so, Phil took two long steps and launched into the air. At the apex of his leap he blocked the shot; the ball floated like a shot bird. As Phil soared out of bounds, Ty recovered it, brought it up, and passed to the far corner, where Will waited. His three-pointer snapped the net, tying the game. John Malatare’s voice cut through the gym: “Here we go now!”

With five minutes and twenty-seven seconds remaining in the season, the game was tied. Phil brought the ball up, defended by Caleb Bellach. Phil drove right, then crossed to his left. Caleb followed, but when Phil crossed back to his right, the defender briefly lost his balance. Phil brought the ball up, a pump fake. Caleb overcorrected just enough to allow Phil to pull the ball down, duck underneath, and scoop in a left- handed layup. Zanen yelled. It was time.

Arlee’s devastating press hadn’t yet fully materialized, but at the end of the third quarter, Zanen had run time off the clock, letting his team rest to prepare for one great surge. Now, as the Eagles inbounded the ball, Ty Tanner and Alex Moran dropped back toward the far basket. Greg and Will stayed up near the inbound line. Greg fronted the point guard, denying the entry pass. Phil shadowed Caleb at midcourt, threatening to intercept a lob to him while still maintaining position to descend on the point guard should he break free from Greg. Will offered a small amount of room to Parker Dyksterhouse—a trap. The Eagles inbounded the ball to Parker and Will was everywhere, his hands like windshield wipers. Parker dribbled from side to side, looking for an opening. As he turned, Will poked the ball away, back toward the basket. He grabbed it and jumped, laying the ball in. Four-point game. Phil and Greg trapped again, forcing a turnover; Alex dove for a loose ball; Tyler spun for a layup, then Alex shot a great arcing three-pointer and ran up the court, thinking of his late mother’s promise and knowing it would rip the net.

The pass came with two minutes remaining in the season. The Warriors had a nine-point lead. Phil darted toward the corner, chasing a rebound. Out at the three-point line, Will raised his arm, then put his head down and sprinted toward the far basket. His hair tailed behind him and his arms chugged in a stiff way, the tattooed wings on his left shoulder a blur.

Phil chased down the loose ball, drawing two defenders. Before they could trap, he made a brutal and swift motion, at once controlling the ball, whirling, and cocking his arm. His face took on its most clear expression: eyebrows arched, cheeks drawn, eyes hard. On the bench, Zanen knew what was coming and that he was powerless to stop it. The full-court Hail Mary brought mayhem under normal circumstances. To throw it with the season on the line was borderline insane. The noise in the gym was a boiling roar. Phil snapped his arm, sending the ball toward the gym’s roof. The sound flattened out, thousands of eyes followed the orange sphere’s path, and underneath it, Will ran.

Phil threw the pass intending for a final, decisive blow. It crested, tumbled, and landed in Will’s outstretched hands just beyond the three- point line. The crowd detonated. He moved to his left, one dribble, then two, and launched off his right leg, mouth open just beyond the defender. He flipped a layup off the backboard with his left hand. The ball rolled around the rim and fell out. Caleb Bellach grabbed the rebound and took off. Will tailed him, almost out of air. Caleb pirouetted through the defense and scored. Seven-point game. Zanen wanted the boys to bring the ball up slowly, to force Manhattan Christian to foul. They only needed patience. But Will once again saw an opening at the back of the defense. Again he took off, head down, a half step ahead of everyone. From behind the baseline, Phil arched his eyebrows, pursed his mouth, and reached back. Zanen could not believe it. Phil let it fly. This time the ball moved in a low plane, hard and fast. When it smacked against Will’s outstretched hands, it seemed to propel him. He planted his right foot ahead of the defender. He flung the ball upward; it floated off the backboard; his body crashed to the court, where it stayed, spasming. Zanen and Greg ran to him and pulled him off the floor. His sweat left a trail on the wood, and he smiled, because the ball had fallen through the hoop.

With fourteen seconds remaining, the game stopped. On one end of the court, most of the players stood with their hands on their hips or knees, waiting for Ty Tanner to shoot a free throw. On the far end of the floor, Phil’s attention was focused elsewhere, looking for a face to match to the voice in the crowd. He had first heard it coming from the stands moments earlier, following an inbound play during which he and Caleb Bellach shoved one another: Redskin.

Phil stalked away from his teammates with an elastic gait, brow down, mouth small, eyes hard, and glared into the seats.

John’s voice boomed through the gym: “Phillip! Phillip! Phillip!”

Phil never reacted to the crowd. But that word was different; it severed some internal cord. He yelled into the stands.

“Too close!” yelled John. “You got fourteen seconds left! Fourteen seconds!” Lane Johnson loped across the court and put his hand on Phil, offering deep teenage wisdom. In his recollection, he said, “Who cares about them?” Phil gave a final long look and returned to the game. Will went for a steal and committed a foul. During the free throws, Phil stepped in to box out Caleb, who stood at least three inches taller than him. Caleb could dunk; Phil could not. But when the shot bounced off the rim, Phil maintained his position, elevated, and grabbed it with one hand. He pulled it down as Caleb returned to the floor. Caleb fouled Phil and hung his head. Phil stalked to the far foul line. Greg came to slap his hand, but Phil took it and held on as though offering a gift. Then he made the free throw. The clock ran out, the buzzer sounded, Ty hurled the ball in the air, and the town of Arlee rushed the court. Zanen held his wife and wept. Then he turned to Thomas Lyles’s brother and they embraced. Lane Johnson put on a vest that had belonged to his deceased uncle. David Whitesell went to Greg, worried that his son’s tears were ones of relief rather than joy. Alex Moran wept for his mother, Lynette. Ivory felt something large rushing through the place, something he called “this crazy feeling of infinity.” Phil turned toward the voice in the crowd, flexed his skinny arms, and roared. Then he buried his head in John’s shoulder. Will wandered in a daze, a feeling of warmth flooding him. High above, in the second deck, Sophie Haynes left the confines of her wheelchair. She stood.

Adapted from Brothers on Three by Abe Streep. Copyright © 2021 by the author and reprinted by permission of Celadon Books.