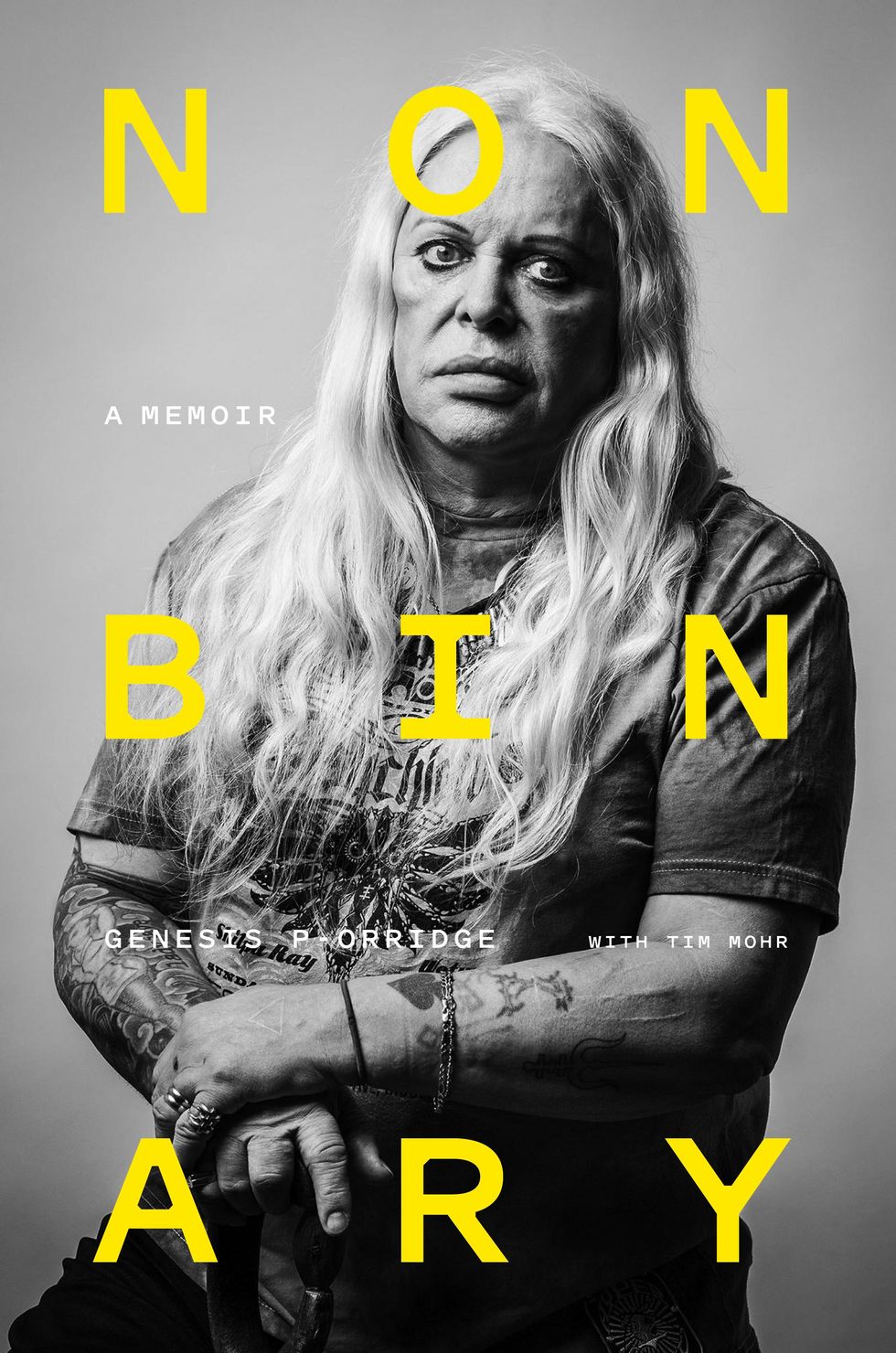

Genesis P-Orridge, who passed away in March 2020 from leukemia, has left behind an unmatched legacy — and he/r new memoir, Nonbinary, cowritten by best-selling author Tim Mohr, is considered the artist's final work to inspire new generations of queer trailblazers and thought-leaders.

The iconic inventor of "industrial music" and advocate for eradicating gender norms has never been stuck in one place. Between he/r upbringing in Britain, which circled an explosion of radical, new music in the '60s, to developing he/r own projects Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV, Nonbinary traces this 70-year-long evolution in the arts.

Below, read a PAPER exclusive excerpt from chapter 39 of Nonbinary, available now via Abrams Press, which focuses on P-Orridge's relationship with Ian Curtis of Joy Division fame.

My feeling, looking back at my brief but precious friendship with Ian Curtis, is that he and I were intensely similar. We were both born in post-war, bombed-out Manchester, and we both viewed our experiences in a minute-to-minute way, seeing life as a metaphor for an ultimately fatalistic destiny. We would often express this futility in self-hatred. For failing to make people understand, failing to make them really SEE the hypocrisies and the betrayals, the pain of existential dilemmas.

Ian would usually call me late at night. This is back in the day of the landline. Perhaps it was from Jon Savage, or perhaps someone else, but he got hold of my private telephone number and began to call me. He would call me at odd hours to talk about Throbbing Gristle, to talk about my anarchic ideas on popular music. I had, after all, named a totally new genre of electronic rock, which imbued me with some serious credibility.

Ian was a great talker on the phone, and smart. He turned out to have been an aficionado of Throbbing Gristle from as early as 1977, when he bought our first album, Second Annual Report, mail order directly from us. Apart from any common drive to subvert and inflame popular music, we would also talk about militaria, transgressive acts, Nazis, William S. Burroughs, suicide, sociopathic tendencies, and, needless to say, depression and isolation.

When D.o.A. came out, Ian loved the track "Weeping."

It turned out I wasn't the only one who thought he was being used by his band. Ian felt the same way about Joy Division. We understood each other's hopeless situation completely. We wished we were somewhere else with a group of our own, a new group.

"Weeping" remained Ian's favorite song of mine. Sometimes he even scared me with his devotion to it. He'd play it to me over the phone and softly sing the words along with my vocal. Joy Division released "An Ideal for Living" in June of that same year, 1978, and he gave me a signed copy. People ask me years later what Ian Curtis was like. What did he dress like? What kind of drugs did he do? What were his political views? What kind of music did he listen to?

He dressed scruffy. Pullovers. Jeans. Unremarkable.

He drank beer. Smoked a cigarette now and then.

He didn't have any political views. Couldn't have cared less.

We both loved Frank Sinatra.

Listen to "Closer" sometime, really closely, and you can hear the Sinatra influence. The careful phrasing. Sinatra's phrasing blew Ian away. One time I can distinctly remember the two of us sitting in my squat in Hackney, listening to "Laura" sung by Sinatra. It must have been the middle of the day, because I remember turning up the stereo to drown out the sound of traffic outside. Ian was staring at the jacket of the LP as if it were some holy document.

He liked Jim Morrison, too. And the Velvet Underground's nihilism. But he liked Sinatra more.

Some afternoons we'd kill time in a Nazi memorabilia shop called Call to Arms, run by Chris Farlowe in an Islington antiques mall. Chris had had a hit single covering "Under My Thumb" by the Rolling Stones, using the resulting windfall to indulge his Nazi passion. I had bought one of Hitler's table knives from the Berlin bunker silverware there for just ten quid.

Ian would paw around some of the uniforms, try a jacket on. A Hitler Youth belt. He thought the Third Reich had the best uniforms, that Speer had a really sophisticated sense of style. Most of the time, we walked right back out, empty-handed.

The rest of his band was always into getting drunk in some pub somewhere. They didn't get him. Never would. They'd tell him to have another beer and shut up.

Do you think he'd ever dare tell them he'd been listening to Frank Sinatra?

Genesis and Tanith, 1980 (Photo courtesy of The Estate of Genesis P-Orridge)

There were only two people he really confided in by late 1979 and early 1980. One of them was Annik, this beautiful Belgian woman who worked for the record label Factory Benelux; he'd met her on tour, with her perfect pouty lips shaped by speaking French in that super-seductive way. He was so in love with her. He was still married to Debs, and they had a baby daughter, Natalie, too, but there was no going back.

I was the other person he confided in that fatal year. I was his father confessor, in a way. I was ten years older. It was never a matter of having some deep conversation, some tearful heart-to-heart. He wasn't like that. In fact, I remember the silences more. Long silences. So much guilt filled those brooding silences. His eyes lighting up when he suddenly had come to some firm conclusion deep in his mind.

Once he reached for his pack of cigarettes, then remembered I didn't allow him to smoke in my apartment. I hated the smell. We'd been talking about the upcoming Joy Division tour of America. The conversation had dropped off earlier. But now he'd circled back.

"I'm not going," Ian said.

"Then don't go," I said.

"They keep telling me I'm going to be on tour," he said. "But I'm not going to do it."

It seemed as if a weight had been lifted. Decision made. He had a sense of invisible, relentless steamrollering behind the scenes, and this was compounded by feeling he had ended up exactly where he didn't want to be. Feeling obliged to take part in a truly dreaded American tour. He spoke of a sense of betrayal, of being used, of claustrophobic relationships, his fear of flying, letting Deborah and Natalie down, disappointing Annik, who he truly loved, of being eaten alive by everyone and destroyed. He felt weak and trapped. Sucked dry. It was a toxic combination.

He believed that his own lack of courage had created this situation. Commercial blackmail and misplaced loyalties had destroyed the integrity of Joy Division. Matters had somehow been shabbily manipulated in such a way that, despite his cries for help, he was scheduled to fly to the U.S. on May 19, 1980.

"Shall we listen to 'Laura'?" I said, reaching for the Sinatra LP. He nodded his head, in a mildly better mood suddenly. "Cheer you up?"

"Laura is the face in the misty light...," Ian sang, smiling at me as I set the needle down. A few seconds of static and then that perfect, gem-like phrasing.

A few weeks went by before I heard from Ian again. It was one of those late-night phone calls. We were talking about Throbbing Gristle again, and he told me he wanted to be as irreverent, innovative, and provocative. He'd seen a small pressing of our single "We Hate You (Little Girls)" backed with "Five Knuckle Shuffle," which had been packaged and designed by Jean-Pierre Turmel of Sordide Sentimental. Ian loved all the artwork and the concept of a limited edition seven-inch single.

I'd met Jean-Pierre through the mail, because he'd ordered a copy of Second Annual Report and went head over heels for it. He felt it was the next step in culture, the next move. He sent me a copy of what was then a fanzine, Sordide Sentimental, and in a subsequent issue, he wrote a deeply philosophical six-page review of the LP. He sent me that, along with a translation, and I was pleased someone took us seriously: unlike most of the English music press, that, if they initially liked the record, liked it just for being "weird." Anyway, Jean-Pierre and I became pen pals, and he wanted to transform his zine into a label—a label that wasn't just releasing records, but was releasing packages that were sort of cultural anarchy, strategies to change the way people perceived things. Of course, he wanted TG to do the first, because we'd inspired the shift in his perceptions and his aesthetics. Then he invited Loulou Picasso to do the cover art, because he wanted to have different artists do the covers of the things he released, so that he was also engendering support of the art world and showing that that, too, was in flux.

"Do you think Jean-Pierre would be interested in doing a Joy Division single, Gen?" he asked, seemingly unsure.

"I know he would, Ian. He is already a great admirer of your band."

He seemed surprisingly unsure that their music would be interesting enough. I told him I'd connect him with Jean-Pierre in Rouen. And that's how "Atmosphere" happened, released as a limited single by Sordide Sentimental: Joy Division's most valuable musical artifact and, in my opinion, still their most perfect song.

Cynthia and Neil Megson, 1951 (Photo courtesy of The Estate of Genesis P-Orridge)

The experience with Jean-Pierre had planted a seed in Ian's mind.

Smaller instead of bigger. Taking risks instead of staying trapped in a band that had become stale to him. The same way that TG had become stale to me. It was during those late-night phone calls that we hatched a mischievous plan: we were going to organize a joint show in Paris where TG and Joy Division would perform together. Ian, Jean-Pierre, Brion Gysin, Joy Division's manager, Rob Gretton, and I would agree to keep things secret for now. The usual groupies would be there, the other six members of our two bands just going through the motions, waiting for their two lead singers to get over their little art kick and become the usual moneymaking spectacles again.

Ian was laughing on the other end. He didn't laugh much, so I knew this was really amusing him. He could really picture it.

"Then we all come back onstage and have a little jam," I said.

"'Laura,'" he said jokingly.

"They wouldn't get half way through it," I said. "How about 'Sister Ray'?" It was one of our favorite Velvet Underground songs. Joy Division

sometimes played it live as an encore.

"That's perfect," he said.

"And then we come back onstage—just you and me," I said. "And we

announce that we're quitting our bands and you and I are forming a new band together."

Looking back, it's bittersweet. Brion Gysin arranged for me to talk with a booker at La Palace, who loved the idea. Rob, the Joy Division manager, gave the show a green light. I had even traveled to Paris to confirm everything secretly.

But it's the show that never happened.

It's the band that never was.

It's this empty page that haunts me. The songs that aren't. I would love to hear what it would have sounded like. Two Frank Sinatras. I know it would've been something else. I know it would've saved Ian.

That's how close we came. Can you feel that almost erotic sense of purpose and that exquisitely tormenting sensation of irrevocability that devoured us?

We wanted to build something, in this case an aesthetic "jihad" that was not already publicly desired, that nobody in their right mind could possibly want, and then to relentlessly prove that they did want it after all—indeed, leave them feeling that it always existed.

All the while we were converting the outside world to our inner aesthetic, Ian and I were depressingly aware that in the end, the audience and critics understood nothing, respected nothing, and protected nothing of our vulnerability, our genuine pain.

We explained so much, we appeared silent. We moved so many, we appeared still.

I am forced to believe that Ian recognized a great part of himself in the role I was compelled to act out in Throbbing Gristle: careening, searingly adrift, and isolated. During more extreme performances, often bitter, suicidal, and callously nihilistic.

There were two more calls from Ian.

One night, it was short and to the point. He asked me if I was coming to a Joy Division gig at the Pavilion in Hemel Hempstead. I said I would.

The show was a mess. He had an epileptic seizure during the second-to-last song and they had to carry him offstage. Tony Wilson, that prick, was smiling at me. The houselights had been turned back on, making him look even more demonic.

"You're killing him," I said. "You know that?"

"Well, then," Wilson said. "Even better publicity. We'll really clean up." I wanted to punch him, I really did.

The last call from Ian was on the night of May 17, 1980. An abject Ian

phoned me for the last time. He was singing "Weeping" again, but his voice seemed farther away, strange. I was scared for him, because I could sense what was in his mind. I had tried to kill myself to a backdrop of "Weeping," too. He was distraught and severely depressed. He was alternately bewildered and angry. Sick of it all. Sick of not being heard when it was inconvenient for others. With his own personal contradictions and problems on top, I knew that there was not much time.

He felt that somehow he'd let matters slip out of his grasp and control; that nobody around him cared what he wanted, what he needed, and more importantly at that moment, how much he did not want to tour the States with Joy Division.

I listened to him sing "Weeping" and stayed silent.

Genesis P-Orridge playing drums in COUM Transmissions, 1971 (Photo courtesy of The Estate of Genesis P-Orridge)

He wasn't drunk. He wasn't deranged-sounding. He was concentrating on every word. The phrasing as important as ever.

"You didn't see me weeping on the floor / You didn't see me weeping on the floor...," he sang.

I was just listening. I had a terrible feeling. But in hindsight, anyone can say they had a terrible feeling.

"My arm is torn open like a wound," he sang, his voice getting even softer. "My universe is coming from my mouth / I spent a year or two, listening to you / Discrediting myself for you . . ."

When I see myself sitting in the corner of the couch, with the phone pressed tightly against my ear, I can't do more than just listen to him sing. The singing is where it began and ended. Maybe the darkest song I ever wrote could help him begin again.

He was singing me the final words.

"I don't want to carry on / Except I can't even cease to exist / And that's the worst."

He put the receiver down, and it disconnected.

I just knew something was wrong. I rang people I knew in Manchester. My calls went unanswered.

But why didn't I call the police?

The last thing I wanted was for Ian to be suddenly invaded by emergency services and perhaps carted off for more medical and even psychiatric evaluations. Perhaps this was just an extreme version of his usual motive for ringing me up. Perhaps he was just desperate for company and support, to be heard by a person he believed felt the same things just as intensely. I intended to travel up to see him that week if he managed to cancel the American tour.

I phoned someone else in Manchester and told them that I thought Ian was really going to try to kill himself and that they should get to him immediately at home. When I got a curt reply and was asked how I knew, I said I just knew. Somehow the person I spoke with succeeded in putting me into an almost hypnotic holding pattern, persuading me that everything was going to be fine; it was just a prima-donna tantrum and that I should not interfere directly and call anyone else or the police. They promised they'd do something anyway, and they never did. They thought he was just winding me up.

"Just Ian being dramatic," they said.

"No! I really think he's going to kill himself tonight," I pleaded.

It fell on jaded ears.

I was assured that if anything really serious was going on, the Joy Division inner circle would take care of it in their own way. They were used to this kind of thing.

A sense of awful inevitability still overwhelmed me as I hung up. I cried into the night until the Valium kicked in. I wept. The kind of weeping that wracks your body with sobs and screams so deep that they feel like spiritual convulsions.

I could have called the police, but I didn't.

In the end, I convinced myself, just like the rest, that nothing terrible had happened.

They found him the next morning. I'm not sure how long after we spoke he actually hung himself in the kitchen in that very working-class Manchester manner.

Years later, long after Ian's death, I saw Annik at a Psychic TV show in Brussels and we fell into each other's arms. We'd both been his secret friends at the time he most needed to feel he was being heard. The hidden, heart-torn Ian. We were wiping away tears, holding each other. Even after so much time had passed, I could sense, without her saying a word, how much she still loved him.

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge at "Thee Gates Institute," Ridgewood, New York (Photo courtesy of The Estate of Genesis P-Orridge)

From Your Site Articles

- Macy Rodman Tributes Genesis P-Orridge in "Runnin Down My Back" ›

- The Wisdom of Counterculture Icon Genesis P-Orridge - PAPER ›

- Genesis P-Orridge on Love, Death, Gender, and Politics - PAPER ›

- Nonbinary Model Fish Fiorucci on Walking Balenciaga in Paris ›

Related Articles Around the Web