Hamish says he’s not at all vain. He wouldn’t consider getting his teeth whitened. He has an average life, with a happy marriage and two children. But when he caught sight of the top of his head in a family photo about eight years ago, something consumed him.

“I just saw this massive receding hairline and it triggered intense emotions,” he says from his home in Edinburgh, where he works in marketing. “I can feel my heart rate has increased just talking about it. It somehow threatens my identity so much that the ground feels shaky.”

For years Hamish, who is in his mid 40s and prefers not to share his real name, did little about his loss. He was busy, and paralysing shame mingled with dread. But the pandemic changed that. “I’ve had too much time to think, too much time to look in the mirror,” he says. “And throw into that the whole Zoom malarkey, where I was constantly faced with the last thing I wanted to see … It took over my life and I thought: ‘Look, I’m going to get this fixed.’”

Lockdowns have presented a challenge and opportunity to men who are worried about hair loss. Many looked down from unforgiving mirrors and webcams to healthy bank balances. With offices closed, and nights out and holidays on hold, social confinement has also provided the perfect cover for recovery, out of sight. The result is that the procedure is now in unprecedented demand.

The British Association of Hair Restoration Surgery (Bahrs) estimates that the country has about 100 doctors doing hair transplant surgery via more than 200 clinics – 10 times the number there was a decade ago. Transplant tourism has also exploded, particularly in Turkey, where clinics offer package deals including hotels for as little as £1,000 – half the rate at even the cheapest UK clinics. But pandemic travel restrictions have concentrated demand at clinics in this country. Dr Richard Rogers, a veteran surgeon at the Westminster Clinic in London, has a packed diary, and reports a 50% pandemic bounce in inquiries.

Many surgeons do impeccable work. But an increasing number of clinics operate in a follicular wild west, where competition is fierce and regulation is patchy. They tend to prioritise tough sales tactics and search engine optimisation over training and well-equipped treatment rooms. And now they are exploiting the pandemic and the male insecurity it has fuelled.

“Relationships have broken down, jobs have been lost and people want to better themselves,” says Spencer Stevenson, a mentor for balding men, who is known online as Spex. He says inquiries to his own site have quadrupled in the past year – up to 50 messages a day. He says a culture of peer permission is taking root, challenging the stigma associated with balding cures; everyone seems to have a mate of a mate who has had a transplant. “But I feel really sorry for new patients,” he adds. “You’ve got vulnerable, naive men walking into this brutal place.”

Stevenson, 45, was that man when he got his first transplant 20 years ago in the US. It was the era when hair plugs were sparse and unnaturally spaced, like a doll’s hair. Stevenson has since had 12 corrective and further transplants, spending more than £30,000. He now has an enviable mop, and says if he were starting the same journey, transplant technology is such that one or two good operations would do the same job.

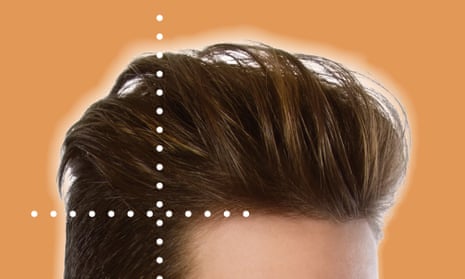

After administering local anaesthetic, surgeons today use a needle-like tool to punch out units of up to four healthy hairs, including their root-like follicles. Thousands of these follicular units can be smuggled out of thicker areas of hair, usually at the back of the head. Doctors then insert these units, or grafts, into balding areas via tiny cuts to the scalp. Some clinics use robots to make the incisions. Patients emerge with thousands of sting-like scars, which heal quickly. The implanted hairs typically drop out in shock but regrow over the coming weeks, like green shoots after a forest fire. It can take a year to see the full results. Done well, a transplant should look totally natural.

Follicular unit extraction (FUE), as this method is known, is in the highest demand, including at less reputable clinics. An alternative, known as follicular unit transplantation (FUT), involves the slicing out of a strip of scalp. This string-like length of hairy flesh is then sliced into units for implantation. FUT can yield more grafts for extensive transplants, but also leaves a bigger, permanent scar.

When the Guardian asked men to share their experiences of hair transplant surgery, more than 100 responded. Most were happy. “It was fantastic,” says Matt, 40, a postman from Devon, who went to Istanbul for his transplant last October, when travel restrictions were relaxed. He paid £1,450, including three nights in a hotel. “It didn’t really hurt and I’m very happy with the results so far.”

James Collins, 26, is from Newcastle and travelled to Birmingham in January for his £5,000 transplant. He had always avoided being photographed because his receding hairline got him down. He says that while he wasn’t hiding his transplant, lockdown let him recover without facing questions from friends. “It has made a world of difference to my confidence,” he says.

While none of the respondents had suffered serious adverse effects, some patients said they had regrets. They sought a comforting bedside manner and value for money, and were shocked to discover a world of upselling, poor communication, unqualified technicians, and treatment rooms that, in the words of one dismayed patient, felt more like a “store cupboard”.

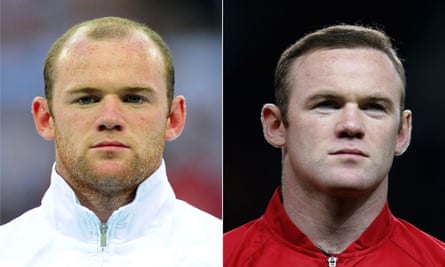

Tom is in his late 30s, and also prefers not to use his real name. He has watched his hair retreat for eight years. “My other half loves it – Jason Statham is his ideal man – but it just didn’t make me feel confident,” he says. At first Tom’s partner talked him out of surgery. But the comedian Jimmy Carr changed his mind. Celebrity recipients have helped drive the boom since Wayne Rooney restored his hairline in 2011. Carr revealed his pandemic transplant on TV last year. “What else are you going to do in lockdown?” he said.

Tom hit Google, which is often where the trouble starts. Searches for “hair transplant” yield millions of results, the vast majority of which are for competing clinics. “Classic red flags are: ‘We can get you in tomorrow’, ‘We’ll offer you a discount’, and ‘We’ve just had a cancellation’,” Stevenson says. “What you want is a clinic who can’t get you in for six months; where the price is the price. But when you’re vulnerable, you hear what you want to hear and a lot of clinics know what buttons to press.” Other warning signs, he says, include claims of “guaranteed results”, “unlimited grafts” and “scarless surgery”.

Reports of botched transplants are common and Rogers, at the Westminster Clinic, says he is frequently called to repair them. Greg Williams, a former NHS burns surgeon, switched to hair transplants in 2012. He is now president of Bahrs and lobbies for better regulation. There is no register for cosmetic surgery because it’s not a recognised medical specialism. “But I would suggest hair transplant surgery isn’t cosmetic – it’s a treatment for a medical condition,” he says. Recognition would increase regulation. In the meantime, it is left largely to clinics to set their own standards.

Tom went with a clinicthat said it would charge £2,000 for FUE, transferring an “unlimited” number of grafts (a maximum of 3,500, when you check the contract). Within minutes of a brief consultation, Tom says he was pressured into paying a deposit of £1,000. He says there was no talk of additional fees. He was called to a second consultation in February, three days before the procedure. “They said: ‘We suggest these PRP injections or the transplant might not succeed,’” Tom recalls.

Platelet-rich plasma treatment (PRP) involves re-injecting a patient’s own blood after the platelet cells that play a role in blood clotting and healing have been concentrated. Athletes use it to help recover from injury, and there is some evidence that it may improve recovery in some patients after FUE. “I’d paid the deposit so I didn’t feel like I had a choice,” Tom says. “I didn’t want to give them any option of the transplant failing and then them saying: ‘Well, we warned you.’” He paid another £800 for PRP to be administered in the weeks after the transplant.

Tom found the FUE procedure painful. “Apparently I’m a bit of a bleeder so they had to give me blood clot pills,” he says. He says technicians chatted among themselves, and that he was only given information about what was happening when he asked for it. Tom said the doctor in charge of the procedure frequently left the room to supervise other patients. His account is echoed by Arjun (not his real name), who had a FUE transplant at another clinic last month. “They have doctors to supervise but they’re not doing the entire procedure,” he says.

Arjun, who is 44 and moved to the UK from Nepal 20 years ago, says he lost confidence after no longer being able to wear his once lustrous hair in a ponytail. “My hair was the last thing I wanted to lose,” he says.

Because transplant surgery involves cutting the skin, any provider in England must be registered with the Care Quality Commission (CQC) or the equivalent bodies elsewhere in the UK. The commission tells me inspections have been paused during the pandemic, but that “monitoring” continues (it encourages anyone with concerns about a clinic to get in touch).

Beyond that, there is only guidance for clinics to follow. The General Medical Council and the CQC recommend that only a registered and properly trained doctor should remove or implant hairs during a surgical procedure. But there is no law to prevent anyone cutting into a patient’s scalp. Nor is there recognised training for FUE. It is perfectly legal for a doctor to supervise multiple transplants a day, bringing down the price of treatment.

Tom remembers feeling groggy when the implantation stage started in the afternoon. He says the doctor came into the room and recommended yet more additional treatments – another round of PRP to be administered on the day, as well as mesotherapy (vitamin injections with a scientifically unproven effect on hair loss). This would cost another £750, bringing the quoted £2,000 up to a total of £3,550. Tom says the doctor himself brought a payment terminal to the operating table. “I’m sitting there, blood coming down my head with people sticking scalpels into my head and they say this will give me a better chance of success,” he says. “I was in their hands and was unable to even research what they were offering.”

Rogers, at the Westminster Clinic, says he carries out one transplant a day and completes all the work himself. As a result, he charges from £5,000 for extensive FUE treatment. He says there is no need for PRP to be decided, or payments to be taken, on the day of a procedure. “That should be taken care of beforehand,” he tells me.

After 10 hours in the clinic, Tom went home. He says he wasn’t warned about the rigorous care required after a transplant, including bandages, scarring and constant spraying of the head with saline solution to avoid infection. He told his employers his webcam had broken to avoid being seen on Zoom for the first few days. “I would never go through it again, it was just awful. It’s one of those things where knowledge is power,” he says. “You expect surgery to be traumatic but you also expect surgeons to do everything they can to ease it.”

Arjun, who works in a hospital, says he also felt pressured into buying PRP and that the operating room did not feel like a place for surgery. There was no sink in the room for handwashing, for example. “It felt like a store cupboard,” he says. He also thinks he didn’t receive as many grafts as he needed to fill in his balding areas. His procedure started hours later than scheduled, and Arjun thinks it was rushed.

A few days after Arjun left a one-star review on Trustpilot, the reviews site emailed him to say that the clinic had flagged his review as bogus. This is not an inconceivable claim; I have seen evidence of slanderous attacks on clinics generated by rivals via Facebook pages or fake reviews, and Stevenson tells me that fake five-star reviews are also rife. But Arjun left his review under his full name.

Stevenson is not remotely surprised to hear about the experience of Arjun and Tom, who are waiting to see the full effects of their transplants. Stevenson says hundreds of clinics around the world operate in the same way, because they can. “They’re vultures,” he adds.

Williams, the president of Bahrs, says standards are so low that many surgeons don’t know what a good transplant should look like. “Some men are just happy to have a few hairs back, but a great transplant today is something even your hairdresser won’t know about,” he says. A bad transplant can leave moved hairs unnaturally spaced or growing in strange directions. Donor regions at the back of the head can be left with noticeably sparse coverage.

Hamish’s own transplant journey is not yet over. When he made his decision, he considered jumping on a plane to Turkey. He says it’s easy to seek a quick fix when you’re vulnerable. But something told him to hit pause.

He did deeper research, including via Stevenson’s website and Bahrs, to help him navigate a blizzard of claims and offers. He is due to go under the knife this year at a reputable London clinic, where he is prepared to pay thousands more than he would have done in Turkey. “I’ve been looking for anything to get over the anxiety and panic,” he says. “I just want to get on with my life.”