We’ve lost too many important rappers over these past few years, in startling succession and at tragically young ages.

Throughout April, DMX, Black Rob, and Shock G, all genre pioneers in their 50s, died within weeks of one another. Just a few months earlier, in December 2020, MF DOOM’s wife revealed the masked-face villain had died two months before—a jarring announcement that couldn’t help but remind many fans of the 1993 death of the rapper Subroc, DOOM’s brother, in a fatal car accident. (DOOM’s cause of death remains unknown.) 2020 also claimed Malik B, a founding member of the Roots, along with too many other up-and-coming talents like FBG Duck, King Von, and Jordan Groggs, a member of Injury Reserve. In New York City alone last year, the coronavirus took Fred the Godson’s life, while 20-year-old (and already legendary) Pop Smoke was shot and killed. To this day, I still regularly hear Pop Smoke and DMX’s ferocious, gripping songs blasting from cars in my Brooklyn neighborhood.

Hip-hop heads are no strangers to the shockwaves of death. The two single most acclaimed and influential rappers of all time were gunned down in their prime, their murders still unsolved nearly three decades later. Countless other rappers have explicitly resigned themselves in their songs to just two paths forward in life, death or the system, while paying tribute to friends they’ve lost along the way. The scale of this morbidity has now reached a new pitch: murders, overdoses, suicides, vehicle accidents, chronic health conditions, all occurring again and again. In 2018, writer and academic Jesse McCarthy dedicated his magisterial essay “Notes on Trap” to “the many thousands gone,” specifically naming six rappers who never made it past their teens, 20s, or 30s; in 2019, music critic Craig Jenkins wrote that we were “losing another rap generation right before our eyes,” noting, among many others, the successive deaths of Lil Peep, Fredo Santana, Mac Miller, and Nipsey Hussle. The toll has only heightened since then.

These deaths hurt so acutely for many reasons: They are emblems of the longtime oppression of Black Americans, the discriminatory systems that either failed or actively neglected them, and the consistent persecution of their modes of expression; several of these rappers never made it past their middle ages, if they even made it there at all; the mourning and calls for an end to these tragedies have been sounded for decades; hip-hop’s long fight for mainstream acceptance, and its staggering success and longevity across nearly five decades, cannot save its artists alone. I’ve recently been thinking a lot about two more gutting elements of these casualties: the loss of the stories these rappers had yet to tell, and the sheer decimation of hip-hop’s recorded history.

This came to mind when I watched the Season 4 opener of Uncensored, the TV One docuseries that features hourlong interviews with notable Black celebrities about their lives. In March, the producers of the series landed an interview with DMX; three weeks later, he was dead, his body having given in after a heart attack sent him into a seven-day battle for his life. The Uncensored special ended up being the last interview he would ever give. It is this footage, and a posthumous album due this Friday, that we now can add to his legacy, with regrets that there could only be more.

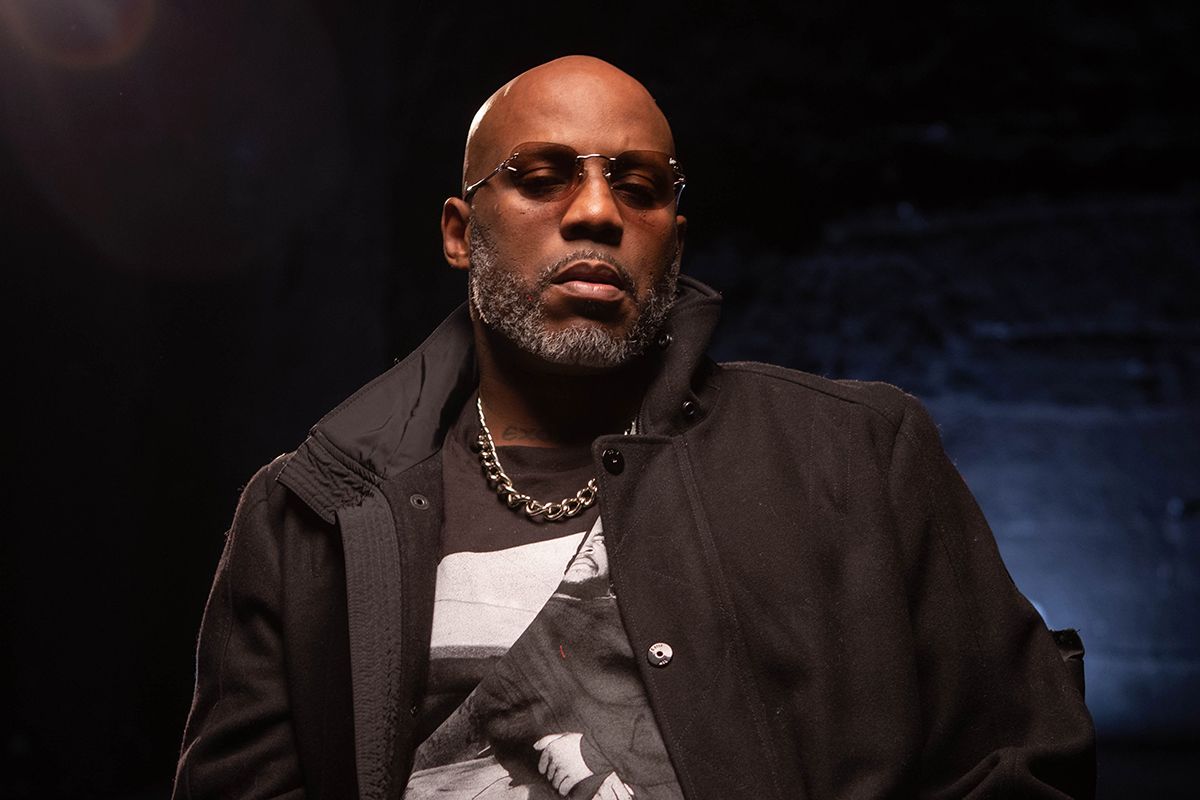

The special provides an incredibly detailed, poignant, and moving interview. DMX, clad in glasses, a chain, and a shirt with a vintage photo of Ice Cube, thoughtfully recalls details of his struggle-filled, influential life and career. Spanning his entire life, from his childhood troubles to his early career and eventual world-shaking fame, the interview shows us the late rapper in many different modes. We see him pray on camera and invoke his devout faith; we hear him candidly recount his difficult relationships with his parents and ex-wife, as well as his love for his children and his deceased dog, Boomer; we receive life advice from him, told straight to the camera. Most piercingly, X refers to how he once thought he “wouldn’t live to see past 20” and mentions how blessed he feels to have proved himself wrong. He says that he “would like to look back on my life before I go and just thank God for everything.” What we get from the interview, beyond the awe-inspiring stories of X’s life, is a true American story, an honest reflection of life in a cruel country that forces Black artists into nightmare circumstances and relentlessly punishes them for trying to escape.

Watching this special, I was transfixed by its rugged candor, the legacy reckoning, and the eye-popping archival footage. It made me wish that X’s contemporary Black Rob—who’d been in and out of prison since his Bad Boy days, screwed over by Diddy, suffered from myriad conditions, and was homeless for a while—had also gotten a chance to tell his stories in this way, and not from a hospital bed shortly before his April 17 death. I wished that Shock G could’ve reminded the world about how the Digital Underground changed popular music altogether, beyond even the monumental achievements of giving the world “The Humpty Dance” and a rapper named 2Pac. I wished posthumous albums from rappers like these weren’t mostly incomplete, hastily clobbered-together affairs likely out of line with the artists’ visions. I wished that all the rappers who’d suffered so much pain and died so young could’ve had forums like this one to be so thorough and vulnerable on camera, free spaces to expound on the personal details that mean the most to them, instead of being pushed by podcast hosts and radio shock jocks to start shit or act antagonistic toward one another.

Today, rap scholarship is in a disappointing place. So many of the websites that populated the blog era are gone now, nigh unsearchable even through the Internet Archive. The incredible rap magazines of the ’90s—Murder Dog, Vibe, the Source, Rap Pages—that boosted the careers of a number of the rappers I’ve named here are all either defunct or have become merely aggregation and nostalgia machines that get basic facts wrong, while their important old material remains inconveniently archived at best. General music publications that may not have the resources—or frankly, interest—to dive into the continually incredible underground rap scenes out there are shuttering or phoning in their coverage of Black music. Recent rap documentaries have often been heavily flawed, fudging facts or deferring too much to the genre’s Great Men, discounting the producers, engineers, background artists who made the genre great—not to mention, also often overlooking rap’s women. There’s never been a truly excellent rap biopic (no, not even Straight Outta Compton), and there is a whole host of others that could stand to be made. The already stark generational gaps in rap knowledge are deepening by the day, in part thanks to this decimation of rap media with editorial, factual standards that’s gotten to the point where readers and writers ask if there are any good rap publications anymore. Countless albums, compilations, and mixtapes are missing from streaming services and the file-sharing websites that used to host them. Fragile CDs and tapes and records and digital files stored in scattershot places are often the only remaining archives of so many artists and scenes. We’ve long known that corporations don’t care about preservation, but it’s still shocking to see the wasteland their disinterest has created.

To be fair, there are astounding hip-hop archives and exhibits around the country, with more, like the Bronx’s Universal Hip Hop Museum, being developed. There are still writers and historians and websites and podcasts and newsletters keeping up the good fight, and books being released that are absolute treasures of knowledge. There are journalists taking it upon themselves to figure out the circumstances of, say, Mac Dre’s murder, while police shrug such cases off. But it’s overall a bleaker, emptier, less-well-funded operation than ever before. When we lose old-school rappers or neglect the ones who are still alive, we miss out not only on their amazing lives, but also on their stories and their chances to correct the record—which they’d be happy to do, if someone asked. Why should DJ Quik have to burn his Death Row royalty check on Instagram Live in order to call attention toward his reasonable ask: for credit on and compensation for songs that most people don’t know he directly worked on?

I mention all this to emphasize, again, the abyss left behind when rappers die young, without support or ample coverage of their life and times. All the people I’ve mentioned in this piece—and many more I wish I could fit in—made undeniable impacts in all sorts of ways, shifting the creative landscape, inspiring other artists and downtrodden people, connecting deeply with fans who can relate, telling their urgent stories about life is really like in a neoliberal society. Their words mattered too much to too many people to allow their legacies to be undercovered and underappreciated by neglect, incomplete histories, messy media archives.

We need to be better to our marginalized communities and creatives. Rappers may still often be demonized by the American mainstream—but they are humans making human works, and they should have the chance to live the long, fulfilled lives they are entitled to. And when they pass, no matter how young, we need to keep their memories alive and refuse to lose them. I do not exaggerate when I say there’s too much at stake.