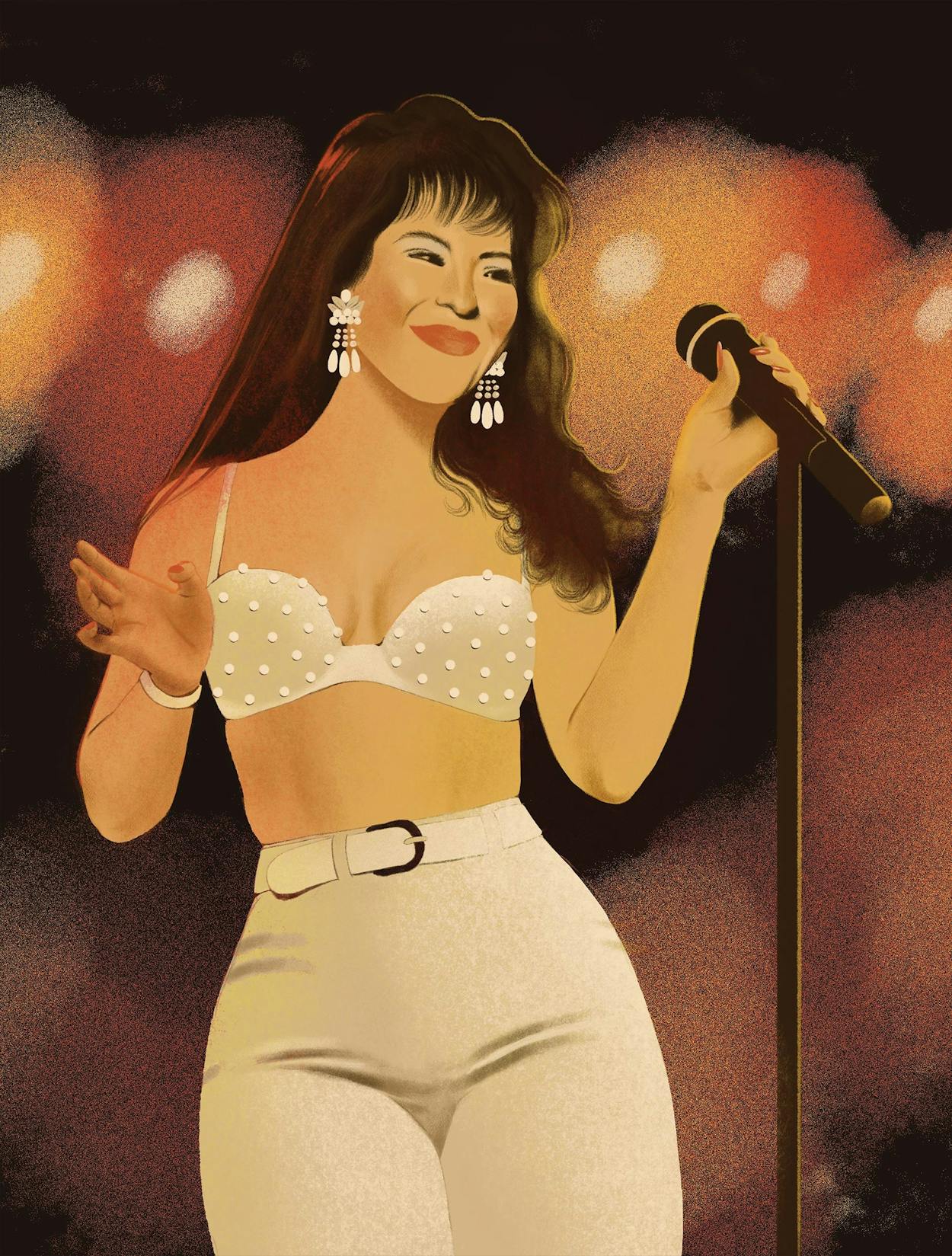

You have to start with the right bra. If you start gluing rhinestones onto any old brassiere lying around, you’re bound to fail. “It won’t look the same,” says Monica Peralta, a 27-year-old Selena fan from Los Angeles. “It really won’t!” She recommends a sturdy bra from Victoria’s Secret or Carnival Creations—one like Selena would have used.

To recreate Selena’s timeless, bejeweled bustiers, Peralta has studied countless photos, as well as interviews with the late tejano singer’s family members, to glean clues as to how her intricate stage looks came together. On her YouTube channel, which has more than 10,000 followers, Peralta documents her process so that fans can learn how to pay homage to La Reina with meticulously embellished clothing. Over the years, she’s delivered tutorials on how to replicate Selena’s hair, makeup, statement hats—even the studded leather jacket she wore to the 1994 Tejano Music Awards. The demand for such tips makes clear that, for Selena devotees, there’s much more to the singer’s appeal than just the music.

Today, her songs remain a force for many reasons, none more powerful than her insistence on simultaneously elevating Tejano culture and propelling it into the future. Though she wasn’t raised speaking Spanish, early in her career, she sang tejano songs phonetically in their traditional language. At the same time, she and her band stretched the definition of the genre by singing in English and working disco, R & B, and funk flourishes into her tunes.

Yet we rarely talk about how Selena’s fashion sensibility evoked a similar tension. “I find that Selena’s interest in fashion often gets diminished to, ‘Oh, she likes glitter,’” says Maria Garcia, the El Paso County–raised creator of public radio’s Anything for Selena podcast. Such an attitude radically undersells how interesting Selena’s fashion sense was. As in her music, she refused to accept the binary of staying true to your culture or eschewing it. She chose a different path, embracing her culture while also demanding that it evolve.

As a fashion icon, Selena unabashedly celebrated her Mexican American heritage rather than conforming to Eurocentric beauty standards. Few Latino celebrities made much headway in nineties American popular culture, and those who did often dealt with the cruelties of racism. In his autobiography, for instance, Ricky Martin writes about never feeling truly comfortable on the set of General Hospital, where he landed a role in the mid-nineties, and coming to believe his Puerto Rican accent sounded “horrible.” Pop stars in the Mexican entertainment industry, such as Paulina Rubio and Thalía, tended to have fairer skin and lighter hair than Selena did. Both Rubio and Thalía attempted English-language crossovers and played up their whiteness to varying degrees.

That is what made Selena so different, says Garcia. “At the time, you never saw people like that on television, even in Latin American programming.” Selena chose to emphasize the shape of her lips with a bright, signature red tint; she embraced her perennially frizzy, dark brown hair and her body type, which didn’t fit a size-zero mold. (One episode of Anything for Selena is titled “Big Butt Politics.”)

Today, Selena’s image is an essential part of American style—which likely would have seemed unimaginable to her when she was trying to carve out a space for herself in U.S. pop culture.

Selena’s look mirrored the sartorial choices of Texas’s Mexican American working-class communities while simultaneously drawing on the influence of some of her pop star idols, such as Janet Jackson, Madonna, and Whitney Houston. Even when she was reaching for sophisticated styles, she did so on a budget. “She wore rhinestones that you could tell were rhinestones,” Garcia says, laughing. “She wasn’t trying to pretend that she was wearing diamonds.” To create the splotches on the cow-print outfit she wore at a 1991 performance in San Antonio, she used black sequins available for purchase at any craft store. She wore plenty of denim, too, often opting for tight, black, high-waisted jeans onstage, and occasionally employing more rugged, light-washed varieties. Selena took everyday ranchero references and glammed them up a bit—such as that studded motorcycle jacket that now sits in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. In Garcia’s words, she “legitimized” these aesthetics, adorning Tejano touchstones and making them into something to be coveted and admired.

And while Selena’s clothes often bore a handcrafted element, they also had an elegant sheen. At the 1994 Grammys, where she won Best Mexican-American Album, she sported red lipstick and a teased updo, and wore a shimmering beaded gown. The image of her clutching her Grammy while beaming at the camera cemented her status as a new member of pop music royalty—a point driven home when Whitney Houston, who took home Album of the Year and Record of the Year, graced the stage in a similar getup: a glistening, pearl-colored gown paired with a tousled updo.

Selena was shaped by the reigning artists of the day, especially the Black women whose music she was surrounded by during her childhood. “She constantly cited Janet Jackson as an influence,” both musically and visually, says Garcia. She often paid homage to Jackson, once introducing a cover of “Billie Jean” by telling the audience, “This little song is by Janet Jackson’s brother.” And the first time she donned one of her bustiers onstage, she was covering Jackson’s song “When I Think of You.”

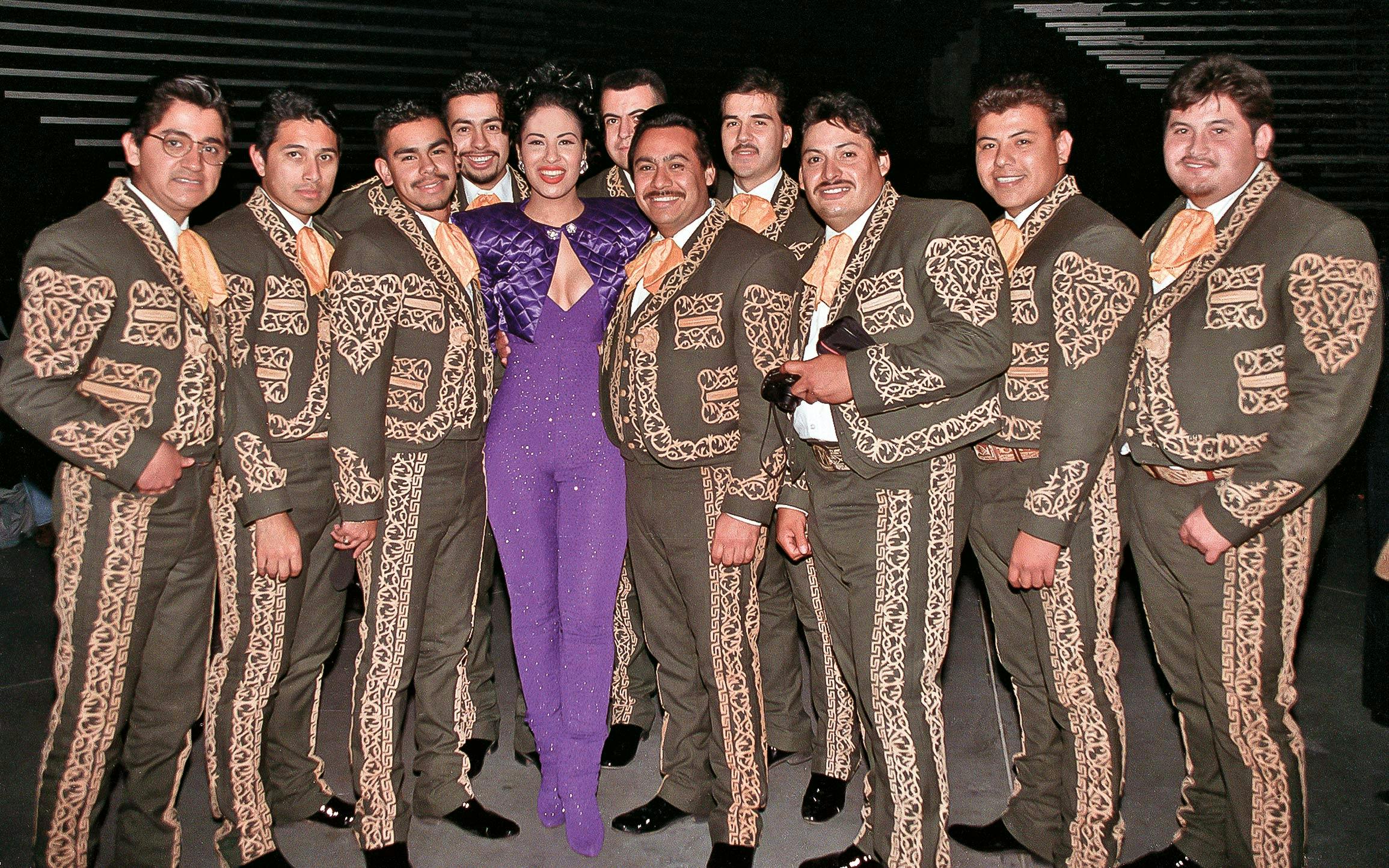

Martin Gomez, Selena’s fashion designer, has said that Diana Ross served as an inspiration for some of the outfits he created for her. This influence is clear in what is arguably Selena’s most well-known ensemble: the purple jumpsuit she wore to her last televised concert at the Astrodome, in 1995. With its bell-bottoms and midriff cutout, Selena was calling back to the seventies—the era she came up in. Her clunky earrings and bold lipstick synced perfectly with the medley of disco songs with which the band started the show. Selena was telling the world something about who she was: a Tejana who felt confident about her roots, and one who acknowledged her debt to Black forebears.

Selena’s outfits often challenged her family’s conservative standards. Her father and manager, Abraham Quintanilla, frequently objected that her aesthetic choices were too revealing. In the 1997 Selena biopic, Abraham and his wife, Marcella, squabble about Selena’s now-famous bustiers: “¡Es un bra!” he shouts in defiance.

As a breakout star in a male-dominated genre, Selena always had men weighing in on her image and her career ambitions. When she signed with EMI Latin, the label heads initially rejected her request to record an English-language album, even though José Behar, the executive who signed her, had presented it to the Quintanillas as a distinct possibility. Marketing decisions fell to men, too. Rubén Cubillos, who designed the cover for her debut album, has said he wanted to play up her “natural” features. Instead, the bizarre final product featured her walking through what appears to be a desert, done up in an outfit that seems nonspecifically exotic. Over the years, as she grew into stardom, Selena seized control of her image and established her own look. By the release of her third album, Entre a Mi Mundo, listeners, as the title suggests, got to enter her world—there, on the cover, is the Selena we know, in a bolero jacket, red lipstick, and gold earrings.

Emboldened by how influential her look became, Selena and Gomez launched a fashion line in the early nineties and opened Selena Etc., a boutique with branches in Corpus Christi and San Antonio. Though much of Selena’s career “had been tethered to her family’s dreams,” as Garcia notes, fashion offered her an outlet to make something truly her own. The stores no longer exist today, despite an unending public interest in the details of Selena’s life and no shortage of fans who seek to recreate her looks. But perhaps that’s because parts of her look have since become ubiquitous. “People still draw from that visual language,” Garcia says.

Today, Selena’s image is an essential part of American style—something that likely would have seemed unimaginable to her when she was trying to carve out a space for herself in U.S. pop culture. Search “Selena Quintanilla” on the online marketplace Etsy, and more than a thousand results for memorabilia—shirts, stickers, key chains, art—still come up, many of them bearing her signature white rose. Celebrities such as Demi Lovato have shown off their Selena Halloween costumes on social media. And these days, Monica Peralta still creates custom bustiers by request for fans who aren’t as confident about their home ec skills. “If Selena were here, I’m sure she would have hopped on the trend of creating a YouTube channel to talk to fans,” says Peralta. “If that were the case, I wouldn’t have to be doing it myself.”

Frida Garza is a writer and editor from El Paso who now lives in Brooklyn. Her work has appeared in Guardian US, Jezebel, ELLE.com, and more.

This article originally appeared in the April 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Selena, Fashionista.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Music

- Selena

- Corpus Christi