Before I learned my body was fat, all I knew was I was a little bigger than other kids my age. I recognized this in small moments, but it didn’t feel too significant.

There was the time my kindergarten best friend and I were in the backseat of her mom’s car, and I glanced over to see her sitting with her thighs easily pressed together. The size of one of my legs took up the same width as both of hers. Where her legs were thin branches that could rest beside one another, mine were sprawling tree trunks I could only bring together with effort.

Or the time a thick layer of fresh snow had fallen in the backyard of our Connecticut home and my cousin and I decided it was the perfect time to go out and play. Armed with plastic sleds, we ran and jumped onto them, ready to glide down the hill. But he was the only one soaring on top of the ice. My body and the sled sunk into the snow with a loud crunch.

Or the time I visited a friend and she wanted to play outside in the melting snow. I hadn’t worn snow pants, so she grabbed an extra pair from her older sister. They barely fit up my thighs, let alone over my belly. Rather than admit this out loud, I pretended I suddenly felt sick and had to go home.

I just knew I was different. Big. Bigger. But it took some time before I knew that I was fat.

By fourth grade, I had already experienced my fair share of body struggles: In gym class, I couldn’t climb the rope nor balance on my hand during gymnastics; I was already sizing out of the kids section in stores; and on top of all of that, I needed glasses (a not-at-all cool thing for kids in the late ’90s).

But at least I loved my class. My best friends and I called ourselves the Jr. Spice Girls. (As the only brown girl in our clique, I was Scary Spice, obviously.) I had a crush on a cute boy. My teacher was the cool dude with a Jeep. Aside from the glasses thing, life seemed pretty great.

During free time one day, I was kneeling at the chalkboard and drawing with some friends. A classmate wanted to use the chalkboard, too. He kept trying to nudge me over to make room, but I wouldn’t budge. Couldn’t he see I was creating a masterpiece here?

Frustrated, he blurted out, “Jeez, do you have to be so fat?!”

There was a sharpness to the way he said the word “fat,” so biting and precise, as if cutting into my lungs and slowly drawing all of the air from inside. I sunk away from the chalkboard, still kneeling, staring at him.

I couldn’t unhear what he’d said. I couldn’t stop the sting from that word that had been directed at me so angrily. I couldn’t go back to the before, when my body was something I used to climb trees or to race across the playground or to play hopscotch. Suddenly, my body was a thing I needed to be aware of, something to be controlled, something bad, something the world had opinions on.

My body was no longer mine.

I wish I could say I have been immune from society’s expectations, that I never wasted a birthday wish yearning to be smaller, that I never hid my body away by swearing off beaches and bathing suits, that I hadn’t stopped myself from having fun because I felt I only deserved happiness once I was tinier, that I never avoided mirrors and windows to stop myself from seeing my reflection.

But those would be lies.

The hate for my body was simply too great — a seed planted by that classmate in the fourth grade and watered by the world around me, from the media I consumed that made fat folks the butt of every joke to the magazines that criticized even thin bodies as imperfect to people in my own family who were perpetually dieting because that’s simply what you did.

The hate came from the doctors who never looked up from their clipboard to listen to any of my issues and instead, with a stern look and dismissive hand, told me losing weight would solve any problem I had. Or the surprise they didn’t hide in their voice when my blood pressure was normal and they’d have to reluctantly tell me I “seemed” healthy. That couldn’t be right, they’d say; lose the weight anyway.

The hate came from the stores that never made clothes in my size, meaning I couldn’t wear the same kinds of styles as my friends, a devastating reality for a girl who loved fashion. Delia’s catalogs and Limited Too simply weren’t meant for girls like me. I was banished from low-rise jeans and baby doll tees not because I didn’t feel like I could rock them but because others had decided my body didn’t deserve them.

The hate came from my own mother, who once took a family photo of me, Pop, and my brother while we were on vacation. It was so hot that I’d decided to wear something sleeveless. After reviewing the photo, my mom — once fat, then thin — pulled me aside. “I cropped this for you,” she said, eyes full of pity as she pointed to where my bare arm would’ve been in the photo. “Because, well… I know what it’s like.”

I believed everything they said about me, and internalized all of the implications that came with it: I was disgusting. I didn’t deserve happiness. No one would ever love me. There was something wrong with me. I needed to change.

In high school, I embarked on an endless round of diets, programs like South Beach and Atkins and Weight Watchers.

I started poring through magazines and online message boards, desperate for tips on how everyone else seemingly remained thin. I learned that Madonna ate mostly popcorn, so I tried that. I learned that some people chewed bubblegum so their mouth was always minty and food didn’t taste so great, so I tried that. I learned that others ate only carefully measured chicken breasts and vegetables, so I tried that. I learned you could try eating very slowly and cutting your food into minuscule portions as a way to disguise how little you were actually eating, so I tried that.

When I inevitably failed, a hunger rumbling so deep in my belly, I’d cry and curse my body and blame myself. It wasn’t the diet that was wrong; it was me, I was sure of it. I wasn’t committed enough. I wasn’t dedicated. Everyone else could do it, so why couldn’t I?

I started going for early morning and late night runs, sometimes tears streaming down my face as I internally hurled insults toward my body as a way to motivate myself to keep going. By the eleventh grade, I was trying to eat as few calories a day as I could, often skipping breakfast or lunch or both. I’d sometimes give myself a paltry daily calorie limit, subsisting on granola bars and diet Red Bull and wondering why I felt faint and had headaches. Then, when the hunger became too much to bear, I might binge on McDonald’s or an entire sheet of Oreos and feel horrible about myself — and then do it all over again the next day. “Tomorrow” became this magical day just within my reach when I would be better, I’d eat all the right things, I’d exercise for hours on end, and suddenly I’d be thin.

I drew inward, away from my friends and family, and isolated myself. If I wasn’t skinny, I told myself I wasn’t allowed to hang out with people or be seen or do much of anything. Yet even at my smallest weight, I still felt I wasn’t thin enough, berating myself daily.

My worst fears about my body were confirmed when I was walking home from school the day before Thanksgiving break. A group of older boys drove by me and one of them leaned out of the car window.

“Hey, fatass!” he shouted, and the rest of them erupted into laughter as they sped away.

I ate nothing that Thanksgiving.

If those around me suspected I might be taking extreme measures to try and get smaller, no one said anything. Instead, every pound I lost was cause for public celebration.

“Have you lost weight?” was a phrase I came to crave. It was all I wanted to hear. It was the validation for which I so deeply yearned.

“Yes!” I would beam, and when they smiled, their eyes looking me up and down in approval, telling me I looked great, I would think, finally, they’re starting to accept me.

Yet the acceptance was fleeting. So often when you lose weight, you gain it back. When that happens, the silence you’re met with from those same people who had been singing your praises is absolutely, unbearably, heartbreakingly deafening.

When you’re at your smallest weight and everyone, including you, is still cruel to your body, then what?

For me, I knew something had to give. In college, I was experiencing debilitating depression and anxiety. I had gained a bunch of weight and I was full of self-loathing. I cursed myself for hating my body when it had been so small, angry for not appreciating what I had then. I retreated into video games and the internet, two things that had always brought me so much comfort as a kid.

Though this was in the late 2000s, I was still clinging to Livejournal, an online blogging platform where people shared updates on their lives. There, I could find two things I loved: fandoms and fashion.

On one of my late night scrolling sessions, I stumbled across a community called Fatshionista and did a double take. Fatshionista? As in, fat fashionista? I was almost afraid to click, worried that this might be a community that existed solely to make fun of fat people; it wouldn’t be the first time something like this existed.

But there were no fat jokes to be found. Instead, the Fatshionista Livejournal community embraced the term “fat” as a simple descriptive term — much like thin — and proudly described itself as “a diverse fat-positive, anti-racist, disabled-friendly, multi-gendered, queer-flavored, politically-engaged community.”

I was stunned. I read and reread the phrase “fat-positive,” trying to understand. Here was this small-ish community, rocking my entire world, and challenging all I had ever believed, with two simple words.

The community was filled with fat folks who were taking and sharing photos of their fat, fashionable bodies. These were real photos of real fat people who didn’t shy away from the camera; they posed proudly and showed off their pictures to others. They were wearing dresses and skirts! They wore short sleeves and sleeveless tops! They showed off their visible belly outline (or VBO for short)! They wore bikinis (AKA fatkinis)! They were unashamed — or, at the very least, in the process of trying to be — and breathtakingly beautiful. For the first time in my life, I was looking at other bodies that resembled mine. That alone felt revolutionary.

The community had rules in place that banned diet and weight loss talk, and on each post, community members complimented and celebrated one another. They had open, frank discussions about the very real fat bias we were experiencing every single day. Here, in this corner of the internet, we could talk about our own experiences freely and openly and know that we’d be understood. Suddenly, the years of grief and anguish I had experienced were validated by others around me. I wasn’t alone; I finally felt seen.

I started to follow self-proclaimed fat bloggers. I tried to get comfortable with the word “fat.” I read discourse about fat politics from people like Lesley Kinzel and Marianne Kirby; I drooled over looks by Gabi Fresh; I read books on health at every size by authors like Lindo Bacon. I realized there was a whole world of fat people out there who were so damn tired of hating themselves and they were fighting to take back their power by demanding respect. I embraced the ideas that fat people — including me — deserved kindness, that we should be able to live our lives free from judgment, that we didn’t owe people our health, that we didn’t need to dedicate our entire lives to shrinking.

These ideas were life-changing. I realized I didn’t owe anyone anything. The only person I owed was myself.

It’s not like I woke up one day and suddenly loved what I looked like. The journey to self acceptance is long and slow and, quite frankly, ongoing. But I started trying to talk to myself the way I might talk to a friend I loved. Would I let a friend speak to themselves that way I spoke to myself? Would I let a friend keep the world from experiencing their greatness?

My efforts started small, the victories seemingly tiny. Wearing something slightly more form-fitting. Deciding that the size on my clothes mattered less than how I felt in them. Buying things I thought were cute. Experimenting with fashion. Embracing mirrors. Taking selfies. Not hiding my belly outline. Wearing a bathing suit again.

These actions slowly but surely gave me back some of my confidence, something I probably hadn’t felt consistently since my elementary school days. I learned to focus less on how big or small I was and more on all the things I could do as I was. I said farewell to the idea of perfection. I tried to embrace the now.

It hasn’t been easy, of course. People on the street, medical professionals, folks in my own circles didn’t all magically start treating me well just because I changed how I viewed myself. Fat people who don’t hate themselves are often seen as threatening, as people who need to be put in their place. But I know my place.

The reality is that I’m fat. But I refuse to let my sentence end there. I’m not just fat. I’m fat and I dream. I’m fat and I’m in love. I’m fat and I create cherished friendships. I’m fat and I’m a mother. I’m fat and I dance. I’m fat and I’m silly. I’m fat and I’ve built a beautiful family. I’m fat and I’ll take up space. I’m fat and doing my best to live life unapologetically. I’m fat and happy.

The secret is there is no magic amount of weight you can lose that will make society give you a stamp of approval and say you’ve done well.

So, we might as well just live.

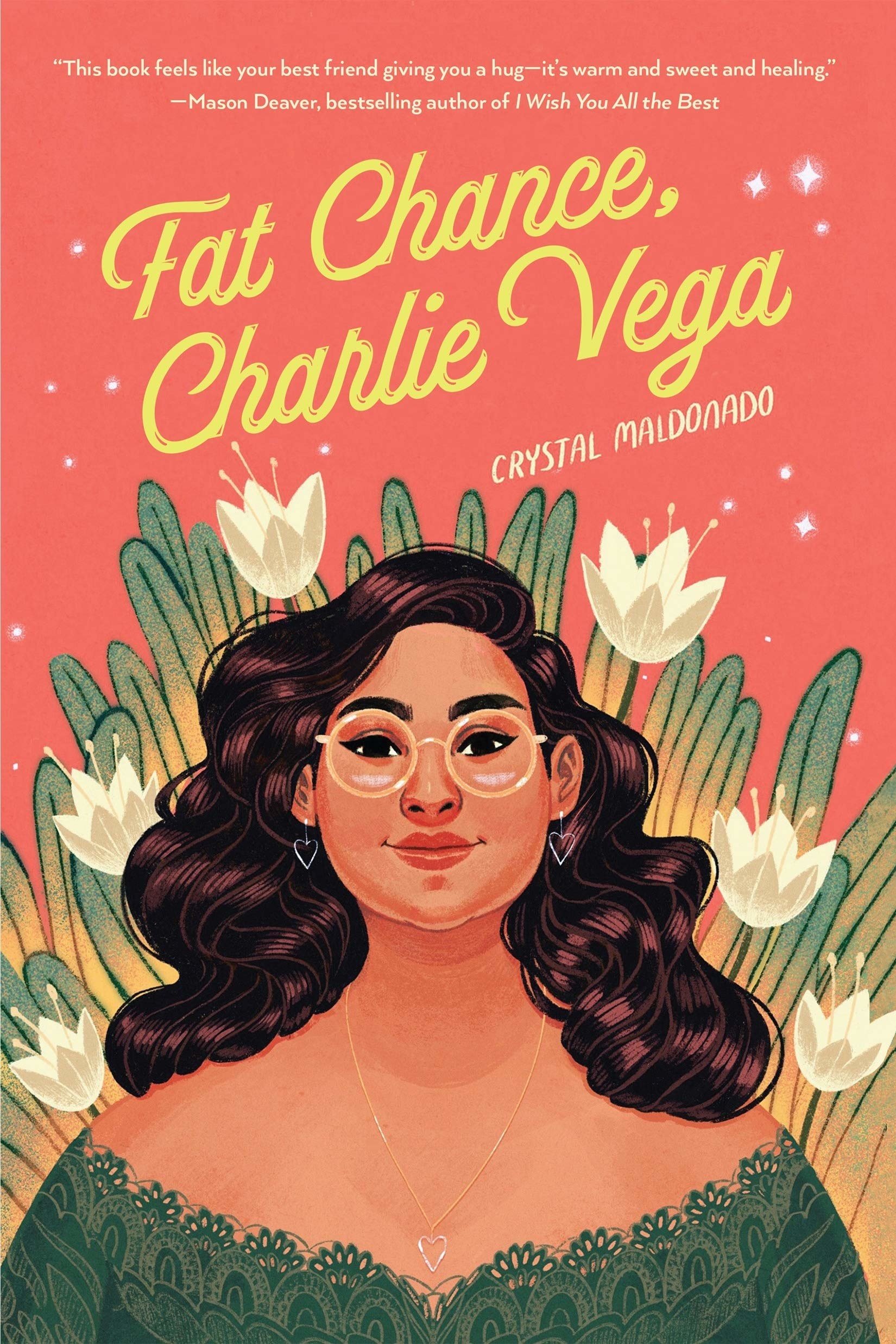

Crystal Maldonado is a young adult author who lives in western Massachusetts with her husband, daughter, and dog. Her debut novel, Fat Chance, Charlie Vega, is a sensitive, funny, and painful coming-of-age story with a wry voice and tons of chisme that tackles our relationships to our parents, our bodies, our cultures, and ourselves. It will be released on Feb. 2, 2021.

Get the book from Bookshop here.