There is a story that Sylvain Sylvain liked to tell about his arrival in New York City. He was Sylvain Mizrahi then, a seven-year-old Syrian Jew whose family had fled Egypt for the US during the Suez crisis. “I was probably one of the last immigrants to sail into New York harbour to be greeted by the Statue of Liberty,” he recalled. “I would be standing there in my fucking brown shoes and people would say, ‘You speak English?’ I’d say no. They’d say, ‘Fuck you.’ The first words I learned when I got off the boat were ‘fuck you.’”

On one level, it’s a grim story about racism. On another, it’s tempting to suggest that Sylvain Sylvain made exceptionally good use of this newfound information: few bands in the early 70s said “fuck you” quite as loudly and repeatedly as the New York Dolls, the quintet Sylvain Sylvain joined in 1971. They were two words that seemed to inform everything about them: their appearance, their sound, their attitude – “belligerent, hostile and defiantly loud”, as a local news report from 1973 suggested; they “don’t give a shit,” asDavid Bowie more succinctly put it – plus the button-pushing and the personal habits that kept them teetering on the verge of collapse and ultimately led to their downfall. Punk rock would almost definitely have happened without them: its confluence of influences that took in the Stooges, the garage rock and British mod bands of the mid-60s and – if you believe Dee Dee Ramone’s account of his listening habits – the Wombles and Bay City Rollers. But it might have been markedly different.

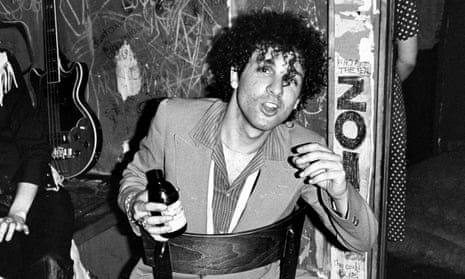

The interplay between singer David Johansen and guitarist Johnny Thunders might have provided the New York Dolls’ visual focus, but Sylvain Sylvain always seemed like the centre of the band. It was him that came up with their name, after a toy repair shop called The New York Doll Hospital, located across the street from the clothes store where he and the band’s original drummer Billy Murcia worked. He came from a family of tailors, bolstering the band’s unique approach to clothing, which bore the influence of New York’s glitter-bedecked queer fringe drama group the Theatre of the Ridiculous and which Johansson described as “very ecological”: their penchant for reappropriating female garments was “just about taking old clothes and wearing them again”.

His rhythm guitar playing was the one rock-solid thing about their sound, which otherwise had a wilfully sloppy, flailing quality that was thrillingly at odds not just with mainstream early-70s rock but also their glam rock peers. It bore little resemblance to the virtuosic guitar playing of Bowie’s foil Mick Ronson, or the taut precision of Chinn and Chapman or Mike Leander’s productions, which was part of their appeal: one of the ways the Dolls presaged punk was that aspiring musicians saw them and thought their limited musical proficiency was no barrier to achieving something similar. And it was Sylvain – relatively abstemious by the band’s standards – who appeared to take on the job of keeping the show on the road.

It proved a thankless task: the New York Dolls had an unerring ability to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory. They quickly provoked a vast amount of press interest – less than six months after their first gig, Melody Maker was calling them “the best rock’n’roll band in the world” – which led to an invitation to come to England and support Rod Stewart, unthinkable for an unsigned artist. But during the trip, Murcia died after overdosing on downers. It was left to Sylvain to call his mother.

The band’s shows at Manhattan’s Mercer Arts Centre garnered a huge following, but they proved unable to capture the excitement of their gigs on their eponymous 1973 debut album or its follow-up, Too Much Too Soon. Producers were incapable of dealing with their shambolic sound. They were booked for a prestigious week-long residency at LA’s Whisky a Go-Go, but the night before they were due to leave, the girlfriend of bassist Arthur Kane attempted to cut his thumb off with a knife while he slept. Sylvain was the first person he called from the hospital.

Another trip to England resulted in a high-profile TV appearance on The Old Grey Whistle Test, where their performance so horrified host Bob Harris that he felt obliged to disassociate himself from them onscreen. “Mock rock,” he sneered, an example of the divisive reaction they provoked, which saw the Eagles slagging them off on stage and Mick Jagger disparaging them in interviews.

As the heroin use of Thunders and drummer Jerry Nolan threatened to tear the band apart, they drafted in Malcolm McLaren as their manager. But his tenure was a disaster: not even their fans were ready for McLaren’s brand of situationist-inspired provocation, which had the New York Dolls playing in front of a hammer and sickle flag and Johansen performing while clutching Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book. By the end there was only Sylvain and Johansen left of the original lineup. McLaren suggested Sylvain join a band he was assembling in London called the Sex Pistols, but the job never materialised.

But the very existence of the Sex Pistols highlighted the impact of the New York Dolls. Johnny Rotten might have written the snippy New York to scorn the suggestion that British punk owed them any debt – borrowing lyrics from the Dolls’ anthems Pills and Looking for a Kiss to underline his point – but it smacked of protesting too much. Pistols guitarist Steve Jones later said that “Johnny Thunders’ guitar was what I really dug” and when Mick Jones was recruiting musicians for his pre-Clash band London SS, the ad stated “New York Dolls style” was “essential”.

Over the years, you could detect their DNA not just in punk but in Kiss’s makeup-caked theatrics (“We broke down the walls for them,” Sylvain noted) and in umpteen hair metal bands, their look a glossier 80s update of the Dolls’.

After their demise, Sylvain occasionally reunited with fellow former members – he played on Johansen’s solo albums and appeared onstage with Thunders – and pursued a solo career: his eponymous 1979 album is an overlooked gem of tight, 50s-influenced power pop. Eventually the band reunited, at least partly at the behest of obsessive Dolls fan Morrissey. Thunders and Nolan were long dead, but a 2004 comeback show at the Royal Festival Hall was rapturously received, before the bad luck struck again: a month after the gig, Kane died of leukemia.

Sylvain and Johansson persevered, and the trio of New York Dolls albums they made between 2006 and 2011 were far better than anyone might have expected, a more mature, lean and disciplined take on the band’s sound. None were big sellers, which if nothing else seemed in keeping with the New York Dolls’ legacy, one in which importance was never matched by commercial success.

It was something Sylvain remained philosophical about to the end, albeit with a hint of “fuck you” thrown in. “Selling out arenas for me is called success in the music business,” he noted a couple of years ago. “We had success with the people. We had success with the artists. We had success with the downtrodden. We had success with the weird. That success lives for ever, because they’re the ones that are creating everything.”