Lose the earbuds. Ditch the phone. How to get the most out of your music

At some point during the pandemic, we’ve all sighed some variation on Willie Nelson’s timeless lyric: “Hello walls. How’d things go for you today?”

Some moments were better than others, Willie. Battling fear, anxiety, rage, mourning and another furious wildfire season, during the most harrowing moments many of us, during the most harrowing moments, desperately lurched into recorded music’s ever-loving arms.

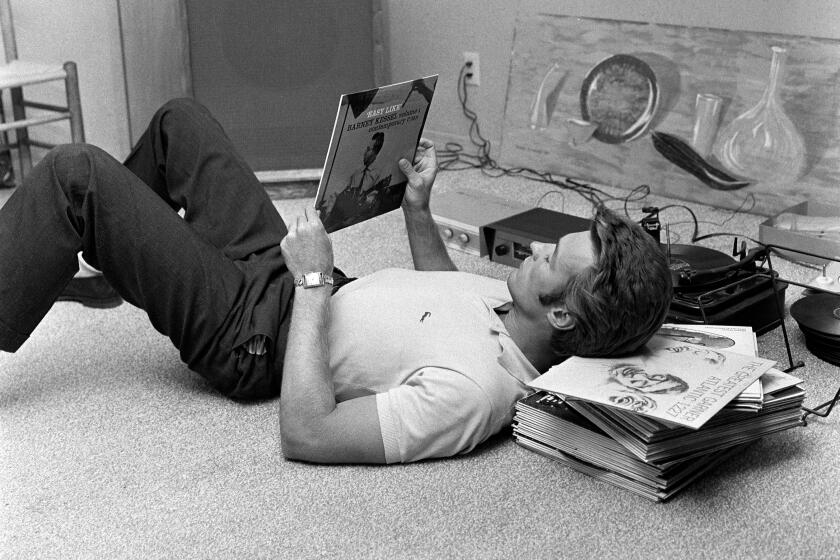

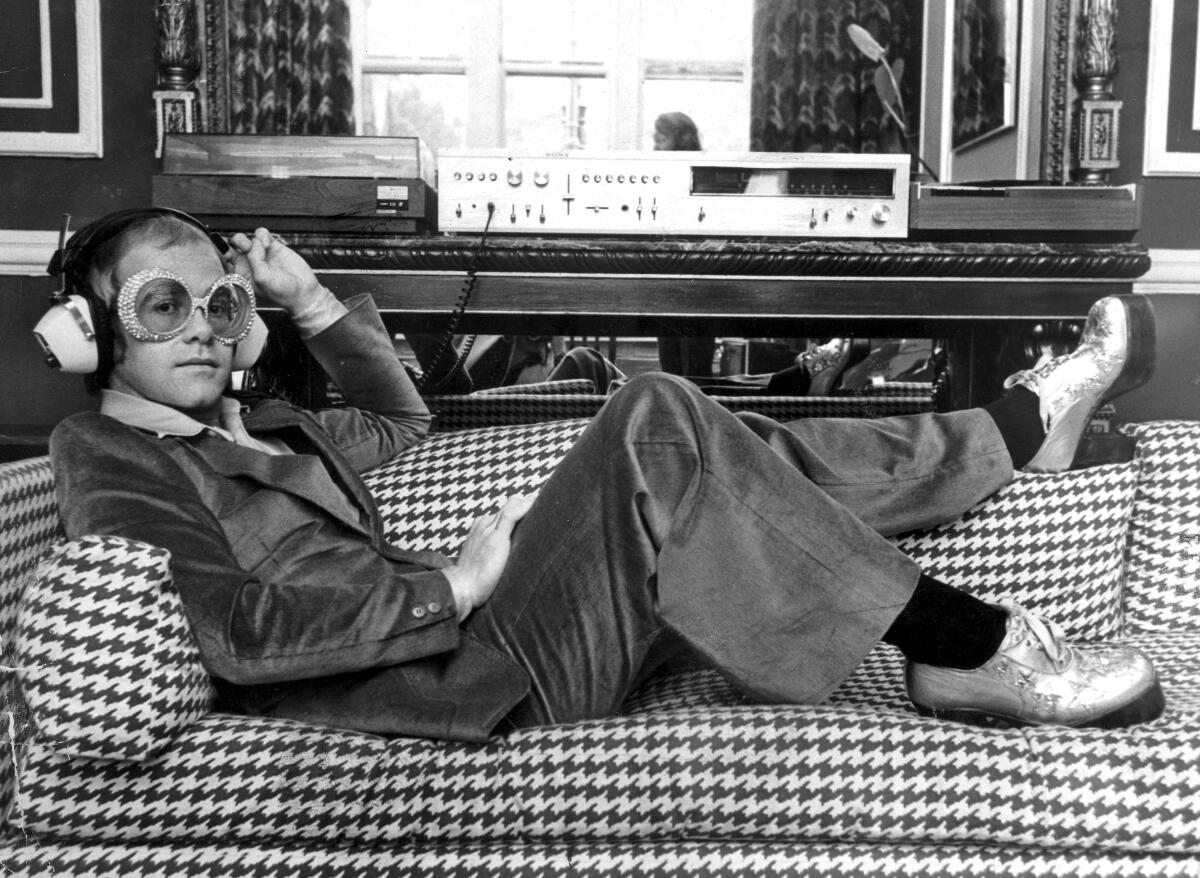

A few months into Our Year of Horribleness, an article I wrote on the value of “deep listening” — making time to experience, with no distractions and at ample volume, great albums from start to finish — went viral. The pitch was simple, a variation on a term that the late composer Pauline Oliveros coined. Hearing and listening are two different things, she advised. During this chaotic expanse, it’s more important than ever to turn off your eyes, the TV and especially your phone for a few hours by absorbing, with intention, excellent full-length records.

How to keep Coronavirus stress at bay: Listen, really listen, to your favorite albums, front to back, without distraction.

The suggestion resonated with readers, many of whom described spending the endless days with specific albums as a kind of salve. Although New York Times critic Jon Caramanica recently confessed to being unable in 2020 to enjoy full albums — or even full songs — in favor of 15-second TikTok clips, for many the act of long-playing wasn’t just a coping mechanism, but offered a revelatory, profoundly spiritual respite. Maybe it’s a West Coast thing, but like very good dogs begging for belly rubs, music freaks willfully opened their eardrums to extended conversations — “Hello, speakers” — with sound.

After watching psyche-testing sorrow and reality-denying anti-mask ignorance on TVs and phones, vanishing into extended therapeutic sessions with Nina Simone, Madlib or Kid Cudi felt like the only rational response.

“We’re bombarded with so much negative press — from the political to the catastrophes of people dying — and all of this is communicated through screens,” says Wes Katzir, owner of the Arts District-based audio store Common Wave. “Music’s a valid escape — ‘I can’t take anymore. I’ve got to tune this out.’ People found music again, and it’s a beautiful thing to witness.”

Absent the option of live music, this listener craved proximity and clarity, or at least the illusion of it. I figured that, like a powerful telescope aimed at distant galaxies, a serious amplifier fueling my estate-sale-procured 1975 vintage large Advent speakers and cobbled-together component chain would bring me closer to the magic itself.

At least that was the rationale when, on a journalist’s budget, I set out to transform my home office (a raw, unconverted garage) into an acoustically sublime listening room.

When finished, I’d strategically rearranged my mess of storage containers, rolled-up rugs, bookshelves, cardboard boxes and VHS tapes along walls to absorb sound waves and build an acoustically awesome listening space. Cardboard egg cartons rule. Would Marie Kondo approve? God, no. Though not every object in here brings me “joy,” the combined mess sounds remarkable.

A $120 investment in a digital-to-analog converter (DAC) early in the pandemic seriously upped the fidelity in my sound cave when using Bandcamp, Spotify, Tidal or Apple Music. When used in conjunction with a laptop, that DAC, teamed with two recently introduced high-definition music streaming services, Qobuz and mega-platform Amazon Music HD, confirmed that on-demand audio for even the most persnickety listener has arrived.

One listen to the recently unveiled remaster of Janet Jackson’s “Control” offers indisputable evidence. When, during the title track, the sound of a sampled car crash captures her state as she sings the line, “I didn’t know what hit me,” it sounds as though the wreckage is flying across the floor in front of you. Synthetic hand claps seem to pop near your eardrums like a string of cartoon bubbles.

Coupling a high-definition service with a basic, no-frills stereo amplifier, laptop, DAC, pair of secondhand speakers (and nice speaker wire) and quality headphones will noticeably improve your listening experience.

But know: You might soon find yourself cruising Craigslist for used audio gear during off hours. If you’re not careful, a few days later you might even end up at a house on a secluded block in Monrovia, $600 in hand, where a genius audiophile named Anthony captures, restores and refines the good stuff. He sold me a late 1970s Harman Kardon power amp that turns your speakers into Mystic Vessels of Sonic Truth.

I know this to be fact after repeatedly — some would say compulsively — playing at full volume Los Angeles-based composer and harpist Mary Lattimore’s 2020 instrumental album “Silver Ladders.” Sound seems to inhabit the room in three dimensions.

When at one point the sound of gusting wind hitting a microphone drifts into Lattimore’s ethereal harp tones, it seems to come at you from the far end of the horizon. On the mesmerizing 10-minute piece “Til a Mermaid Drags You Under,” frequencies feel like they’re cascading from one back corner of the room to the other, with heavy bass tones whirlpooling below.

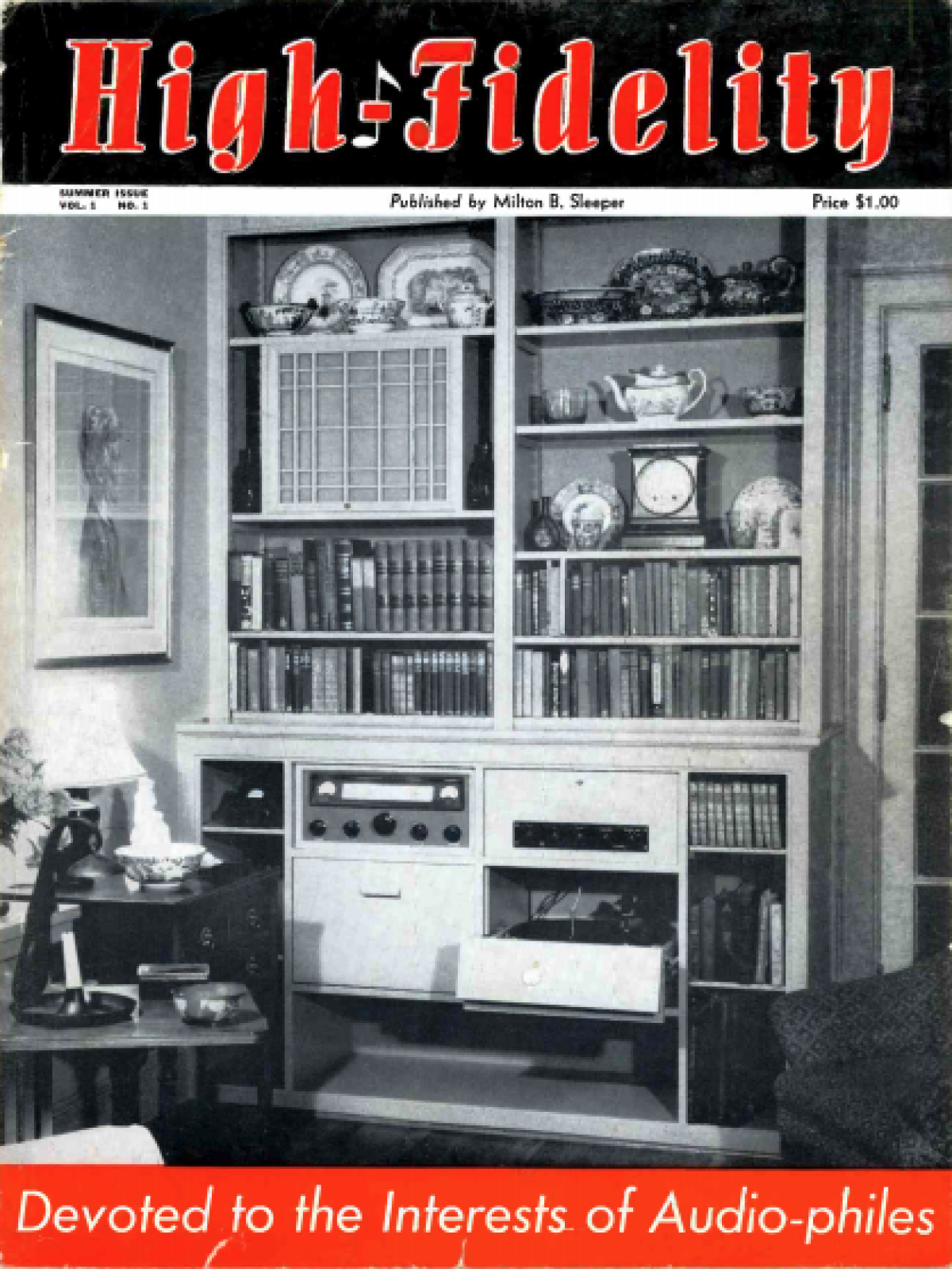

In the first issue of High Fidelity magazine in 1951, founder Milton Sleeper described a letter he’d received from a subscriber whose husband was an audiophile. He loved to show off his stereo to visitors, she wrote, and “has made everyone who hears his system very unhappy, because it is so much better than that with which they are familiar.”

Noting that she was “disturbed at first,” her husband corrected her, mansplaining “that people do not know what high-fidelity reproduction is, and therefore they have to be shown. I now see his point and agree one hundred percent.”

Seventy years later, many people again don’t know what high-fidelity reproduction is and need to be shown. Conditioned across the ’00s by compressed MP3 files and 320kbs streaming files, a plurality of music fans long ago ditched the tangle of wires, boxy speakers and black stereo components in favor of wireless, clock-radio-sized Bluetooth speakers, a Sonos system or Alexa-powered smart speakers. Soundbars have supplanted stereophonic setups. If a home does have a stereo, it’s often in the den chained to the TV, Playstation or an old-school CD/DVD black box.

It’s way more efficient to drop a few hundred dollars on decent headphones and beam waves directly onto your eardrums than suffer through a dozen “well, actually” corrections from an in-store audio nerd. There’s a reason why Apple recently introduced its new Airpods Max luxury headphones ($549) and not an Apple stereo receiver.

Consumption habits have, for obvious reasons, changed during the pandemic. Less commuting has meant less solo time with podcasts, playlists and terrestrial radio. Doomscrolling and endless news alerts have sucked time away from exercise playlists. For music fans in particular, the absence of festivals, concerts, gigs and DJ sets has meant that listeners have lost their ability to deeply engage with an artist’s music for a solid length of time.

Data hints at a shift in spending on audio stuff. In December, vinyl posted its biggest single-week sales tally since Soundscan started keeping accurate numbers in 1991. Surely those buyers are making time to listen to album sides, right? And the Consumer Technology Assn., a trade group representing hardware manufacturers, estimates that turntable units shipped to dealers will shoot up 15% year-over-year and stereo receivers will amp up by 6% in 2021. Sales of these components, however, are dwarfed when compared to the volume of smart speakers and soundbars spreading music into homes.

Anecdotally, component and system sales are up “a little bit” compared with last year at Common Wave. Owner Katzir believes something bigger is at play than mere commerce, though. Whether through headphones, desktop speakers or a fancy system, he says, “the consumption of music has changed, because people now have time to give the music the time it actually deserves.”

He says that some customer interactions have turned into virtual therapy sessions. “Being cooped up at home, now they finally have time to listen to music the way an artist might intend.”

“Awesome audio quality really is within reach. It’s not some esoteric ideal that you would never be able to attain,” says Dan Mackta, managing director of Qobuz USA, which entered the U.S. market in 2019. “If you’ve got a couple hundred bucks to invest, you can upgrade your listen 8,000-fold.”

The French company, born in 2008, was the first music service to sell CD-quality, 16-bit/44.1kHz downloads and the first to offer CD-quality, 16-bit/44kHz files for streaming. Unlike giants Spotify and Apple Music, both of which focus on popular music across their landing pages, Qobuz targets appreciators of jazz, classical and more niche genres — though it offers the same top sellers as other services.

Cranked when listening on Qobuz to “Iron Path,” the ferocious 1987 metal-jazz masterpiece by the quartet Last Exit, the end sounds nigh. A 10-song, 36-minute instrumental record built by bassist-producer Bill Laswell, electric guitarist Sonny Sharrock, tenor saxophonist Peter Brötzmann and drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson, it roars out of the system when the volume knob’s upped. Played loud enough, it can almost drown out the interminable sound of sirens headed to Huntington Hospital.

Amazon Music HD is powered by the largest retail company in the world. More of an upgrade to Amazon Music Unlimited than a standalone platform, the HD tier costs $12.99 a month for Amazon Prime members and $14.99 for outsiders. In addition to thousands of CD-quality albums labeled as “HD” on the platform, volumes of more recent releases and select reissues are available as “ultra HD” exclusives.

The idea, says Amazon Music’s Stephen Brower, who heads artist relations, “was very simply to provide streaming music in a quality as close to the artist intended in the original recording as possible, and eliminate the tradeoff between quality and convenience.”

Willie Nelson first released his song “Hello Walls” in 1962. Faron Young had already hit with it by then, but as one of the era’s rising songwriters, Nelson wanted to make his own mark, so he took to the Liberty Records studios in Hollywood with a band that included session players Billy Strange, the Maddox Bros.’ Roy Nichols and drummer Earl Palmer. The result of those sessions became Nelson’s debut album, “And Then I Wrote.” A masterfully engineered work, it also features Nelson’s now-classic renditions of “Crazy” and “Funny How Time Slips Away.”

For reasons already stated, though, “Hello Walls” has lingered across the past 10 months. No, it’s not about stay-at-home orders or social distancing; it’s a literal conversation between a lonesome, heartbroken fellow and the house that surrounds him. It’s wryly produced: Each time Nelson sings the greeting of the title, backing singers reply with indifferent cheer, “Hello! Hello!”

A great song is a great song no matter how it makes its way into your head. Whether on AM radio or through a $100,000 system, Beyoncé’s “Crazy in Love” will whip your wits every time. If protesters are chanting Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright,” nobody’s asking them to adjust their levels to account for the outdoor acoustics.

That said, love the melodies, hooks and bridges all you want, but don’t neglect the tones, dynamics and precisely placed aural Easter eggs, for within them lie entire universes.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.