The DJ Lag case is one of many where the West ‘forgets’ to credit African musicians

Last week, a track involving will.i.am appeared to heavily lift from DJ Lag’s song ‘Ice Drop’ – but this is just one example in a long history of the Western music industry failing to credit African artists.

Kampire Bahana

04 Dec 2020

Photo credit: composite of DJ Lag ‘Ice Drop’ video (YouTube), will.iam Wikimedia Commons photo, plus record covers for Solomon Linda, Manu Dibango and Golden Sounds)

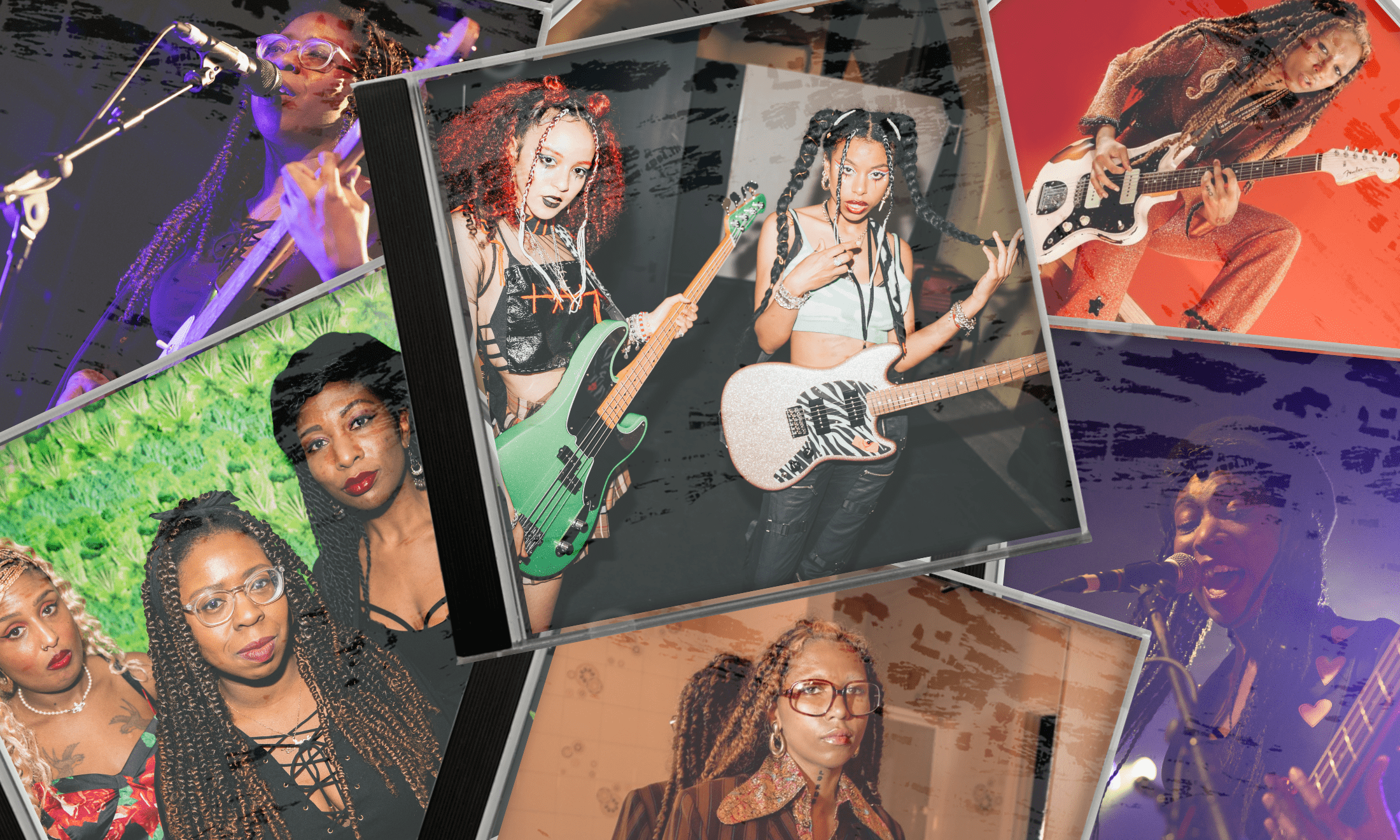

I don’t know what I was expecting when I clicked on DJ Megan Ryte’s new music video for ‘Culture’, featuring will.I.am and A$AP Ferg, last week. As the video began, the definition of the phrase “culture vulture” floated across the screen first. a beat played, sounding familiar, and then the unmistakable double-clap of a loud snare drum.

“That’s the beat for ‘Ice Drop’” says my partner behind me. I didn’t even realise they were paying attention but my partner is right. The similarities between Ryte’s ‘Culture’ and DJ Lag’s ‘Ice Drop’ are numerous and immediately recognisable. The music video for ‘Culture’ too, shares a resemblance to DJ Lag’s 2018 music video for ‘Ice Drop’, which made liberal use of slow-motion and grayscale to present a gritty portrait of Lag’s hometown in Durban, South Africa.

“The history of blatant theft of African music for the enrichment of American corporations is older than ‘M’Bube (The Lion Sleeps Tonight)’”

For those unaware, DJ Lag is one of the originators of gqom, a genre of sparse, rhythm-led music from the townships of Durban. I say “for those unaware” because Lag is gqom’s most successful son, a Grammy-nominated artist, one of South Africa’s bigger electronic music exports alongside Black Coffee and one of the biggest names in the global dance industry. The history of blatant theft of African music for the enrichment of American corporations is older than ‘M’Bube (The Lion Sleeps Tonight)’, but DJ Lag has a song on Beyoncé’s most recent album – he’s not “nobody”.

The phrase “culture vulture” recognises the long history of multinational corporations like UMG and Disney, as well as huge mainstream artists, who repeatedly profit from lifting inspiration from non-Western musical traditions where copyright infringement is poorly defended. “This song is a statement record that recognises the importance of Black cultural contributions around the world,” Megan Ryte originally told Complex, who premiered the ‘Culture’ single. Artists like Drake and M.I.A have been accused of helicoptering into musical traditions from Black communities in the UK and the Caribbean, and unjustly reaping the benefits of collaboration – but at least they credit their collaborators. What’s the expression for American artists who use musical ideas without crediting the author at all?

“The circulation of several thousand nonprofit ethnomusicological records is now directly linked to several million dollars” worth of contemporary record sales, copyrights, royalty and ownership claims, many of them held by the largest music entertainment conglomerates in the world,” says Steven Feld, a professor of anthropology and music at the University of New Mexico in a radio piece for Afropop Worldwide.

“African music, like other resources from the continent, is seen as belonging to no one and everyone; consigned to historical, ‘tribal’ or ‘folk’ collective origins, rather than the individual property of the person who composed it”

The copyright infringement of Manu Dibango’s ‘Soul Makossa’ and Golden Stars’ ‘Zangalewa’ are the stories we know, but American music history is littered with the bodies of African artists who have died paupers while their music lives on in popular consciousness (and rakes in money for Western record labels).

African music, like other resources from the continent, is seen as belonging to no one and everyone; consigned to historical, “tribal” or “folk” collective origins, rather than the individual property of the person who composed it, the way Western musical compositions are seen as intellectual assets. In the digital era, “sampling” or using tracks from existing musical works to create something new, is an accepted element of the popular music industry. In these cases, American and western artists are protected by robust legal frameworks.

Labels and artists register with performing rights societies that track performances and distribution at events, on radio, tv and online. When you play a Black Eyed Peas tune on YouTube, an algorithm recognises it and automatically sends a takedown warning. African artists, many of whose countries do not have active performing rights societies, continue to struggle to collect royalties on their own music, let alone keep track of others’ use of it.

Since the video’s release, South Africans have rallied around DJ Lag, leading Megan Ryte to first turn off comments on the video and several social media posts. The music video, which hit 2.5 million views and 18,000 dislikes in the week it was up, has since been removed. Shortly after the controversy broke will.i.am released a video to apologise…to Megan Ryte first.

“I wanna take the time to apologise to Megan Ryte from the bottom of my heart: Megan, I am truly sorry for putting you in this situation. And I want everyone to know that Megan doesn’t deserve the hate you’re throwing at her because Megan didn’t do anything wrong. […] The person that’s at fault is myself. When the song was turned in, I turned in the credit information to Megan. And I obviously got the credit information wrong. And when I realised I made a mistake, I tried to fix it. And at that point in time it was already too late.”

“While Africans may not have the protection of national music rights bodies or the legal and financial power of major music labels behind them, we do have the internet”

He did not comment on the similarities between the two videos, and also got the name of the DJ Lag song incorrect, calling it ‘Drop Ice’.

If American music history is a long record of uncredited contributions from African musicians, then will.i.am’s career is a lengthy record of music samples that he failed or “forgot” to clear. In some cases, he and his record label have been successfully prosecuted to the tune of many hundreds of thousands of dollars. In other cases, like the mysterious similarities between South African artist Toya deLazy’s song ‘Dreamer’ and will.i.am’s song ‘Dreaming About the Future’, which was licensed for a Lexus car advert, the burden of proof has proved too high to clear against the legal might of Universal Music Group, one of the biggest companies in the world.

On Twitter, DJ Lag’s management company Black Major have assured the public that they are “handling it” and it seems they are, with the video pulled from YouTube less than five days after its release. While Africans may not have the protection of national music rights bodies or the legal and financial power of major music labels behind them, we do have the internet. Last week, South Africans made their collective frustration known and in that way prevented ‘Ice Drop’ from being included in the long list of African songs that remain exploited and uncredited by the American recording music industry.