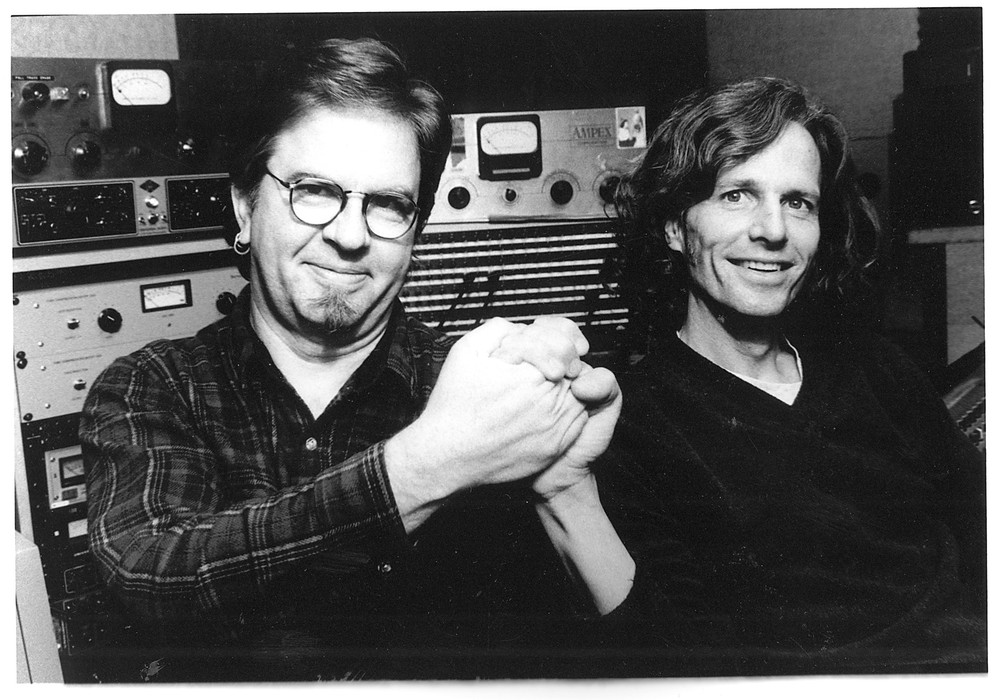

I first met Jesse Lauter in 2009, when we interviewed him for his production and engineering work on the Low Anthem’s Oh My God, Charlie Darwin [Tape Op #114]. We’ve stayed in touch over the years, and even mixed a record together (Sea of Bees, Build a Boat to The Sun) a few years ago. In 2017, Jesse was one of the producers on a documentary about the 50th anniversary Monterey International Pop Festival, and he asked me to help record audio for the production [#120. Since then, Jesse’s worked with a variety of artists, including Tedeschi Trucks Band, Stephen Stills and Judy Collins, and Elvis Perkins. Jesse lives in NYC, but while visiting his native San Francisco, it seemed like a good time to sit down together and chat about Jesse’s views on what it takes to survive as a freelance engineer these days.

As a studio owner, I’ve seen all levels of people calling themselves engineers coming through here. When I see younger engineers coming in who really know their shit, I wonder, “What did they do right that makes them so much more competent?” You’re in that group of highly competent and busy engineers.

That’s very kind of you! I wanted to be a producer, starting at a very early age. I started interning at a recording studio while in high school, around 2002 or 2003 in Atlanta, and the music scene there was booming. I assisted on sessions for CeeLo [Green] and Usher. Outkast was working on Speakerboxx/The Love Below next door, so all of this excitement and musical energy made a big impression on me. But without even really knowing it at the time, I was seeing the fall of the studio industry. Then I went to college for recording at NYU. I was accepted into the Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music in 2005. In many ways I was a natural casualty of the time – someone who wanted to become a music producer at a serious juncture in the music business. I quickly realized, “Okay, this isn’t going to entirely work like it used to. How do you work as a studio engineer in this new environment?” I feel like I was lucky to see the days of yore, and also feel like I’ve been lucky to find my way around in the modern environment.

What do you see as the new skill set that one needs to make their way as an engineer or producer?

I’m a child of Phish and the Grateful Dead, so I was not only raised in studios but concert venues as well. I believe it’s critical for anyone who wants to be an engineer today to have some experience in the live environment. Working in venues, or on the road, both front-of-house and monitors, and learning to multitrack live, is not only going to make you a better engineer but will help you learn how to handle the volume of work that’s required to have a successful career. When I was in college in New York, I started working at every venue that had an available slot. I managed to snag gigs in smaller rooms, and then I started working at Brooklyn Bowl, where I got to work with bigger touring bands, as well as on digital consoles. I actually still keep a day job in the “live realm.” I oversee production at Central Synagogue in midtown Manhattan. I’m not mixing their services on Fridays and Saturdays anymore, but I supervise the production crew and maintain the sound and video systems for one of the most beautiful and historic rooms in the country. It’s very rewarding work, because it’s work of value. And the “God industry” is not going anywhere. I get to employ musicians and engineers who are on the road with major acts. They’re mixing in the room and for livestream, and it’s the most-watched Jewish broadcast in the world. Living in New York does makes for a different economic situation than most places in the country, but you’re seeing it get harder everywhere. Even Nashville’s getting more expensive. Having a day gig and trying to create a situation that works with a producer’s life is hard to come across; but if you manifest it and try to make it work, it can really help.

I’ve always thought that if you want to make records that you care about and like, there’s not always a lot of money there. It’s important to be able to support yourself with some secondary gig so that when a project comes along that may not pay well, you can do it. Is that part of your plan?

No question about it! By having day work and managing my schedule efficiently, I’m actually able to take on low-budget projects and work my prices to make sure it suits an artist’s budget. Because of that, I get to help people out and work with some amazing artists. I would love to get my full rate for every project, but we all know that’s not realistic.

...