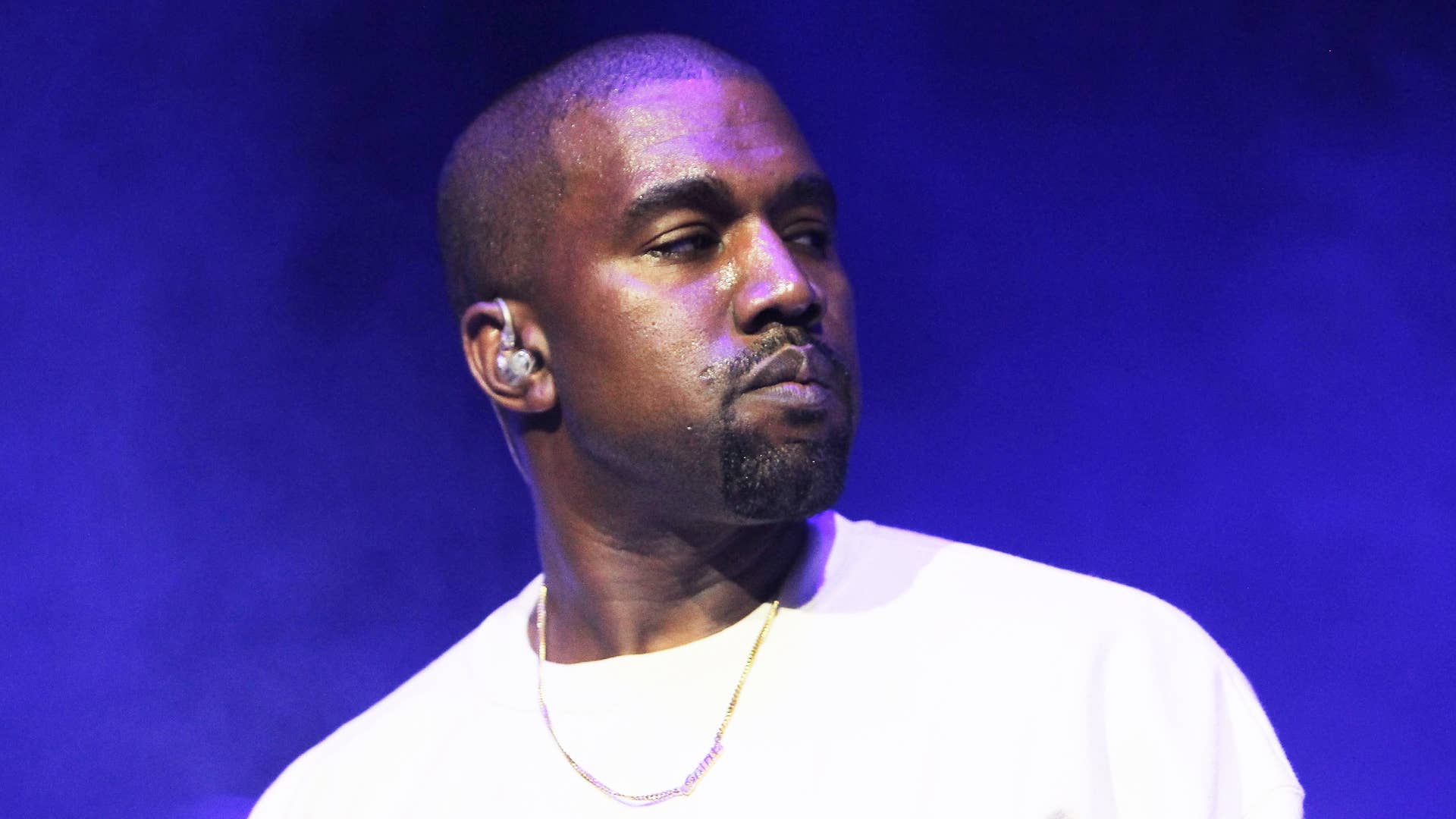

After a tumultuous week in Kanye West’s world—one in which he released over 100 pages of his recording contracts on Twitter, claimed he was the “head of adidas,” and called himself “the new Moses” who would free artists from their recording contracts—he proposed a series of “new recording and publishing deal guidelines” on Twitter yesterday, suggesting that they reflected a strategy for future negotiations on behalf of artists. Like most things involving Kanye, the chaos is paired with bits of truth.

Are Kanye’s new guidelines realistic? What do they mean? In a point-by-point analysis, we break it down for you.

“1. The artist owns the copyright in the recordings and songs and leases them to the record label / publisher for a limited term. 1 year deals”

In the first tweet of his “guidelines,” Kanye appears to be requesting that all copyrighted materials remain in the hands of artists (including master recordings), and that they are licensed to record labels for distribution for one-year periods. Most standard major label deals leave the songs in the hands of the songwriters, and grant ownership of the master recordings to the record label. Kanye has been pretty consistent on this message for the last week or so—he strongly believes that artists should own their masters—but convincing major record labels to accept such less favorable terms seems unlikely without a sea change in market expectations. This short term “license” structure is unrealistic because it is wildly unfavorable for record labels. It provides artists with an ability to elude any contractual obligation they may have to the label on a yearly basis, and that in and of itself substantially increases the leverage artists have in any negotiation. Master ownership is seen as part of the bargain (albeit perhaps a disproportionate one) that provides a label the ability to see a return on their investment in financing young artists.

“2. The record label / publisher is a service provider that receives a share of the income for a limited term. The split can be 80/20 in the artists favor”

In the next tweet, Kanye suggests that record labels should accept an 80/20 split in the artists’ favor on all revenue. This tweet falls into the same category as the first: a contractual provision that isn’t likely to become industry standard without big changes. As we saw last week when Kanye released his contracts, even after becoming a major act, the royalties he obtained for use of his work were between 14 and 1 percent. The framework he suggests, as well “artist/service provider,” is unmatched with today’s expectation, and would require a truly different model for it to become reality.

“3. DEPENDANTS: Artists must be dependent on no one but themselves to manage their catalog. You should need NO ONE else to understand the business you’re in.”

Kanye’s next few tweets seem to represent a high-level wish list to make artists' careers easier to manage. Kanye first states that artists should not be dependent on others to understand their rights and “manage their catalog.” He has a point here: an entire ecosystem has been built around artists to serve various interests, and simplifying or streamlining some of these processes could cut down external costs associated with managing an artist’s career. This is not unlike other areas of innovation in the tech industry. Example: Who uses travel agents anymore?

“4. LAWYERS: The first thing that changes about Record Deals is actually lawyers. We need Plain English contracts. A Lawyers role is to IMPROVE deals…. not charge for contracts we cannot understand or track. Re-write deals to be understandable from FIRST READ.”

The next proclamation points specifically to lawyers, stating that contracts should be in “plain English” and expounding that “a lawyers’ role is to IMPROVE deals...not charge for contracts we cannot understand or track.” It’s important to disclose here that the author of this piece is a lawyer, but this claim is a little presumptuous. As a general principal, lawyers are ethically bound to act in their client’s favor. It is never the intention of a good lawyer to overcomplicate deals so that the artists cannot understand them, but oftentimes negotiating innovative compromises means aggravating simple language. Copyright, especially copyright associated with music rights, is wildly difficult to understand, mostly because it has been written and evolved over time to accommodate both the artist’s right to maintain a range of rights over their work and the public’s benefit in access to the work. This request is not unique to the music industry. As an example, privacy policies have undergone a shift in recent years to become more user-friendly. It’s not impossible that we could see a similar trend with artist agreements at some point.

“5. EQUITY & BLANKET LICENSES ARE THE MAJORITY OF FUTURE NEW INCOME. If you’re with a major you have invested your ‘songs’ as shares in their power to get equity and deals. Almost ALL new deals now are based on ALL songs going to a store or app. The equity is the Artists. NO MORE blanket licenses. It should be clear from day one… what shares you get NOW and when you leave. If your song helps a deal over the line you invested in that store / app same as they did. UMG now has a 2.2 billion share holding stake in Spotify. This is the artists. The system as to how we get share balances on our royalty statement needs to be created and a system on when Artists can cash in.”

This point is a little convoluted. Kanye begins by saying that the majority of future income will come from “blanket licenses” and then ends the tweet by proclaiming “NO MORE blanket licenses.” A blanket license is when a record label (or other group of owners) can license a collection of rights to a user, such that the user does not need to obtain individual permissions. In many contexts that they are used, blanket licenses make licensing music easier for the licensing party. As an example, TikTok and Facebook have blanket licenses for the use of music within their platforms. Similarly, bars and restaurants obtain blanket licenses from ASCAP and BMI to play music in their venues. Without a blanket license, Facebook and TikTok would need to procure individual use licenses from all artists individually; a process that would take time, money and resources. Blanket licenses are an easy, affordable solution to a problem that is otherwise very complicated to fix.

With this background, and seemingly what Kanye is railing against, is the underlying reality that blanket licenses take negotiating power out of the hands of artists and put it in the hands of major labels (as the owners of most of the high value masters). If you think about blanket licenses like a class action lawsuit, individual members of the class may not see much money on their own, but the lawyer will run away with a large chunk of the total award because their royalty is a percentage of the whole group of artist royalties. It’s not that different here. The label has every incentive to enter into the blanket license, but the artists may not believe they are compensated fairly or that their interests are adequately represented. Furthermore, the use case for blanket licenses is, by virtue of its purpose, bent towards a TikTok or Facebook who wants to streamline as many rights as possible and avoid the need to expend resources negotiating licensing agreements with individual rights holders.

Kanye’s appeal here is that platforms like TikTok and Facebook negotiate with artists and grant ownership or shares of the business in exchange for use of music on their platforms. Shares have the ability to increase in value in accordance with the value of the company, whereas a flat rate or percentage may not. Terms of major label license agreements between TikTok and Facebook are not public, but we do know that most (if not all) blanket licenses with performance societies like ASCAP and BMI are tied to a percentage of revenue, which in some ways is not too far off from what he’s looking for.

His next tweet begins, “UMG now has a 2.2 billion share holding stake in Spotify. This is the artists.” UMG has been reported to own a 3.5% stake in Spotify, meaning that UMG makes money not only on revenue as a consequence of license agreements (where the artists share as well) but also on share value as it goes up. Artists will see none of that. From Kanye’s perspective, the label’s prominence and negotiating power is a result of the artist’s works, and thus, this stake should really be owned between their artists and not the label.

Of all of his requests, this is the one that highlights an easy-to-understand unfair concept, and practically speaking, makes sense to fix. In fact, when Warner Music Group sold its $504 million stake of Spotify in 2018, it shared a quarter of those profits amongst artists. Arguably, the only true assets major record labels have are works created by artists. And fairness would dictate that, like a shareholder in a company, artists should be able to properly capitalize on the wealth that a collection of their works creates. Nonetheless, record labels are businesses like any other, and until there are shifts in law or collective action, they will continue to act in their own interests and treat artists’ work like any other commodified asset.

“ADVANCES ARE JUST LOANS!! On Artists re-signing these stop. Advances are Loans with 75% interest rates (or worse). NO other business in the world takes a look at the business, buys shares, starts to profit when it profits. Record Companies have to buy into you, not loan you.”

Kanye goes on to indicate that artists should refuse advances because they are effectively “loans with 75% interest rates (or worse).” Advances often act somewhat like loans, in that they can be recoupable expenses, such that an artist will have to repay the amount of the advance through royalties back to the label before cashing in on the artist’s share. But it’s worth pointing out here that Kanye’s 2012 contract indicates that he negotiated at least some of his advances to be non-recoupable. Also, a significant difference between a loan and a contractual advance. If all goes wrong or a record completely flops, artists are not typically on the hook to pay those costs back, with interest, as a loan would require.

“6. ROYALTIES: Again back to dependents. You need a business manager to read how you did? So you pay to see your money!!! NO MORE. Royalty portals need to show (and do not now) Every song you delivered. Every store you are in. How many streams per song. Income per song. It sounds basic and logical but it does NOT exist. They focus on top earners and ZERO look at the 440 stores…. Only the top few. Artists are global. That’s why their contract territory says GLOBAL royalty department in EVERY label. No more separating finance teams from the music”

“7. PORTALS: Are not just for royalties. They are for your entire business. Every audio file, every asset, every deal stored WITH the money. Money and Music must stay together. When your term ends, download it all. Leave.”

The next two tweets are about “Royalties” and “Portals.” Royalties are the monies paid to an artist for use of their work and portals are the online platforms on which an artist can see their royalty statements. Major label royalty statements are notoriously opaque. These tweets seem to point to that issue, while requesting more transparency in royalty statements. Additionally, major labels usually have royalty departments that operate across multiple labels (under the major) and therefore are a step removed from the artist’s day-to-day contacts. To his point, very few artists make enough money to make the label’s investment in them bear fruit, so it is clearly in the label’s interest to focus on “top earners.”

Kanye concludes his Twitter spree on a hopeful note (and probably the most realistic and strategic point) by saying: “This is a call for all artists to unify. I will get my masters. I got the most powerful lawyer in music and I can afford them but every artist must be freed and treated fairly.”

As I covered in more detail in a piece last week, collective action, like we’ve previously seen in the film industry or professional athletics, is an acute way to ensure more fair contractual terms. This kind of approach, effectively a union, is the most obvious framework for artists to bargain for some of these terms and effectively upend the market standards in a changing world back in their favor. SAG changed the way royalties are dispersed for even the most unknown screen actor member. And it’s not unreasonable for musical artists to bargain in a similar fashion. An action with the most impact here would be to start a union or collective of musicians—only as a group will artists have the leverage needed to undermine these years of exploitation.

Overall, Kanye makes some good points, and he seems, if nothing else, committed to making some impact in the industry however he can. While some of these guidelines are rooted in real industry-wide problems, others are a bit unrealistic and tend to be more likely classified as “part of the bargain” an artist makes with a major label. He is, however, unlikely to be able to do anything on his own here, and there’s been no response from anyone who would indicate these guidelines are, so far, even close to being implemented. It is likely to take collective action amongst many artists to force implementation, but nothing starts without education, and there’s apparently no forum like Kanye West’s Twitter account to garner the world’s attention.

Jessica Meiselman is a New York licensed attorney specializing in entertainment and intellectual property issues