‘I remember going to parties,” says Anna Haigh, “and dancing on buses as we sped along the motorway – to Step On, Hallelujah, Loaded, Come Together, Fools Gold, The Only One I Know, Only Love Can Break Your Heart, Sit Down.” She pauses then more memories come pouring out. “First meeting the Primal Scream boys at the Milk Bar. Hot Soho streets and cold glasses of beer.”

Haigh has every excuse to get misty-eyed about the balmy summer of 1990. Just out of her teens and fresh from backpacking in Morocco, she found herself in the studio with Terry Farley, Pete Heller, Hugo Nicolson and Andrew Weatherall, of the Boy’s Own party crew, adding her fierce Siouxsie-ish vocal to the Bocca Juniors track Raise. Now 30 years old, Raise was a pinnacle of an indie-dance hybrid, one that soundtracked Bacchanalian scenes with its mischievous defiance, rave optimism and punk sass.

Across Britain, dozens of bands from newcomers to old lags were getting remixers in, absorbing the acid house of the previous two summers of love. Gigs became all-night raves. England surged ahead in the Italia 90 World Cup, soundtracked by New Order’s E For England (as World in Motion was originally and flagrantly titled). Pop Will Eat Itself, Jesus Jones, the Shamen, and any number of pilled-up geezers, scallies and urchins such as Flowered Up were crashing guitars and samplers together in the studio. Even the Cure got funky with 1990’s requisite Paul Oakenfold remix of Close to Me.

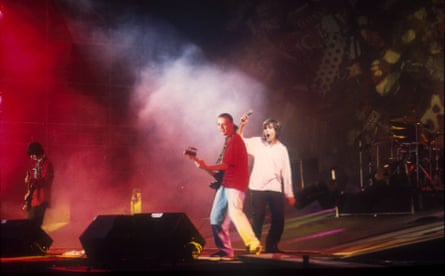

Others are a little less starry-eyed, though. Of the Happy Mondays’ era-defining Glastonbury triumph in 1990, frontman Shaun Ryder says: “I only remember the sex and drugs. I had a bird in me hotel. I’d see her, then I’d go back and sit in the luggage compartment of the tourbus with my smackhead buddies doing gear. The intro to our set was so long because they had to drag me out of the boot of the bus.” And of the Stone Roses’ most fabled gig, the writer Jane Bussman says: “Spike Island was a bit shit. Not anyone’s fault, mind. Everyone desperately wanted it to be Woodstock, anarchy, freedom, joy. But it was on a pile of scorching concrete in a silage swamp.”

The seeds of indie-dance were planted in the preceding acid house years. “Indie-dance is what I was doing all along,” says Paul Oakenfold. “We had two clubs from 1988. Spectrum was acid house, Future was indie-dance. I used to play the Clash, Thrashing Doves, Woodentops, a bit of hip-hop, some Bob Marley.” He cites the sound’s early proponents as “me, Nancy Noise, then Boy’s Own – Weatherall and Farley doing their own thing”.

In 1986, Nancy Noise had gone to live in Ibiza where she heard “Billy Idol, Talking Heads, Yello” and mixed them in DJ sets alongside the Stone Roses and other modern indie. She brought Killing Joke’s Youth, his roadie Alex Paterson and their friends to Future, inadvertently sparking both the Orb and the KLF.

Oakenfold meanwhile worked on two remixes for the Happy Mondays, assisted by Farley on Wrote for Luck and Weatherall on Hallelujah. “They’re both major modern records – pure sex and violence,” says Primal Scream’s Bobby Gillespie. “The Mondays were threatening and we loved that, plus DJs like Danny Rampling and Oakenfold were nice, open, friendly, unpretentious guys who loved music. The scene was inclusive unlike the elitism of indie.”

Creation Records svengali Alan McGee remembers indie and dance colliding thus: “I took Bobby to a Shoom rave in the countryside outside Brighton. Weatherall found me on my hands and knees trying to see if there were any Es on the floor. Bobby was all in black in Chelsea boots like one of the Ramones, and Weatherall looked like some kind of Hell’s Angel. I think there was a spark there.”

Weatherall would produce Primal Scream’s cornerstone album Screamadelica. “There were no boundaries,” Gillespie remembers. Weatherall also remixed My Bloody Valentine’s Soon for Creation (“I forced that one on the band,” laughs McGee, “and I was right to”) as well as James, Saint Etienne and many more. Farley connected with such bands as the Soup Dragons, from the Glasgow suburbs, and Scousers the Farm. Peter Hooton, Farm frontman, says Farley’s touch made them “the toast of London”, while Farley says: “It was the Farm reaching out to me that got my career off and running.”

Other guitar bands had started mutating, too. “People like us and the Shamen started in that C86 guitar indie thing,” says Jon Marsh of the Beloved, whose Happiness album was a comedown soundtrack of summer 1990. “But we’d got our hands on technology and went to clubs. We had become completely electronic by the start of 1989. So much was driven by minds being expanded, by a load of drugs obviously, but also by certain samplers coming out. If you’ve got the imagination or the desire, you can become genuinely different.”

Soup Dragon Sean Dickson says getting the Akai S950 sampler, released in 1989, was “like having a psychedelic tool from above handed to you that could bend and twist whatever came into your head”. New Order’s Gillian Gilbert adds: “People were listening to dance hits like Voodoo Ray by A Guy Called Gerald and going, ‘How do they do that?’ It was a bit like the second wave of punk – people being inspired by it then doing something.”

Like all good movements, indie-dance had its own clothes, helping the sound earn another name: baggy. Scallies in Liverpool were first to revive flares, but Mancunians took them to extremes. Fiona Cartledge of the Sign of the Times shop, where ravers in London sourced their Duffer and Stüssy, remembers: “I sold clothes to Leo, who did the ‘On the sixth day God created Manchester’ T-shirts. He introduced me to Go Vicinity, who made the massive baggy jeans for the Stone Roses. We stocked them and had a queue from Kensington High Street through the market to the shop.”

Farley prefers to think of dancers “wearing white jeans and Patrick Cox loafers, ‘No alla violenza’ T-shirts and Destroy jackets, doing the south London mooch to Lullaby by the Cure”. He loathed baggy: “The clobber they wore during Spike Island really was up there with the Wigan Casino brigade [of northern soul fans] in the league table of dance music shockers.”

Something that drew in so many elements, and revelled in such hedonism, would inevitably fall apart. And it was a turbulent time. The poll tax riots, which the Farm’s Hooton calls “a blow to the twitching corpse of Thatcherism”, had happened in March, and the Gulf war loomed. By 1991, the recession had hit hard. Scenes splintered and rave became hardcore.

But perhaps the worm was in the apple all along. “If you went to the Hacienda,” remembers Happy Mondays singer Rowetta, “you’d be on the dancefloor all loved-up. But if you sat in the corner where we sat, everyone was on heroin, cocaine, speed and acid – and arguing about anything.”

One particular drug is remembered as spoiling things. “1990 was the cocaine revival,” says Jane Bussman, “and it is the antithesis of ecstasy: go and buy another waistcoat and stand by the loo, you berk!” Gillespie recalls: “Later that year, when people moved to cocaine, things started to become more paranoid and edgy.”

Hooton agrees: “There was a genuine feeling of brotherhood, but cocaine reared its ugly head and people started to become self-centred and violent again. I hated the lad culture of the mid-90s: it epitomised everything we were against, even though some people wrongly argue we started it. Some of the Britpop bands copied our hairstyles and clothes, but they were a million miles from the attitude of 89-91.”

Nonetheless, while it lasted, the sense of creative possibility was real and intense. Oakenfold remembers Spike Island fondly, from his vantage point in a DJ booth up on a tower: “It was electric, a sea of people. It came right in the middle of something that was changing music - and we knew it. I thought, ‘Wow, I’m part of this!’”

Hooton thinks the fraternity between scenes and cities was genuine. “During that summer,” he says, “there was a feeling that it was the end of an era and a new dawn.”

“You’d had the Berlin Wall coming down, you had Mandela coming out of prison,” says the Beloved’s Marsh. “Those things fuelled the optimism I wanted to put into the music. It honestly felt like the whole world was changing for the better.” Football was part of it, as singer Denise Johnson, then with Primal Scream, remembers. “Fourth place in the World Cup wasn’t too dusty! It felt like a big party was ahead of us, celebrating being English in a positive way through football, music, the arts and fashion.”

Even the Happy Mondays, for all their debauchery, felt it. “My first song with them went in at No 5,” laughs Rowetta, “then the first tour took in Glastonbury and Ku Club Ibiza. Bloody hell, that’s not the band I went to see in Widnes six months before! It was great in 1989, people were dancing, but it wasn’t the phenomenon it was by the middle of 1990. When the Mondays played the G-Mex Arena in Manchester, or Glastonbury, it was like the whole of Manchester was there, seeing their own up there on stage singing about real things. It was such a celebration.”

And music did change for ever. “We’d had 87, 88, the E thing,” says Shaun Ryder. “By 1990, I was just like, ‘Ah, this is finished now.’ But of course it was just getting started.”

Even if Britpop could be conservative, the nature of music had been transformed: from the Prodigy to Björk, Radiohead and beyond, the possibilities seemed endless. All from, as Terry Farley puts it, “a Frankenstein monster created by young DJs who were blagging it. Stick this breakbeat under it! Loop that guitar! Get the female backing singers up front!”

Shaun Ryder echoes this point: “I used to say to Bobby Gillespie, ‘Fucking Tony Wilson makes me sing on everything. You just do mad tracks with weird sounds and no lyrics. How’d you get away with it?’ It was definitely about what you could get away with.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion