The Master Thief

Sean Murphy was an epic weed smoker, a devoted Tom Brady fan, and the best cat burglar that Lynn, Mass., had ever seen.

It was the play that turned “Manning” into a bad word in Boston. There was a minute left in Super Bowl XLII. The New England Patriots—Tom Brady’s undefeated New England Patriots—needed one defensive stop to beat the New York Giants. On third down, multiple Patriot defenders pushed through the line and grabbed quarterback Eli Manning’s jersey. But Manning slipped away and chucked a wobbly pass downfield, where a mediocre receiver, David Tyree, leapt, pinned the ball against his helmet, and somehow hung on to it as he crashed to the turf. Manning, the interception-prone doofus with the look of a confused middle schooler, would go on to beat Brady in the sport’s biggest game.

Sean Murphy seethed as he watched from his weed dealer’s couch. It was February 2008. Skinny, with deep-set brown eyes, Murphy was a typical Patriots fan. He pronounced “cars” as “cahs,” got his coffee at Dunkin’ Donuts, and had a mullet and a horseshoe mustache, at least when his girlfriend didn’t make him clean up. He moved furniture for a living in Lynn, Mass., a down-and-out suburb on the North Shore, and on Sundays, when he could get tickets, he made the 40-mile drive south to Foxborough to root for the Pats.

But there was another side to Murph, as his friends called him. On Saturday nights he put on an all-black ninja suit and went out looking for things to steal. He was a cat burglar—the best in a town where burglary was still regarded as an art form.

A few weeks after the game, Murphy was at the Boston Public Library, browsing the internet and planning his next break-in, when he came across an article about the Giants’ Super Bowl rings.

Michael Strahan, the team’s star defensive end, had told Tiffany & Co. that he wanted a “10-table stunner”—one that could be seen from 10 tables away in a restaurant. Tiffany had complied, designing a bling-encrusted monstrosity: a thick white-gold band with the team logo and three Super Bowl trophies rendered in diamonds on top. Each ring, engraved on the side with the score, “NYG 17 NE 14,” was to have 1.72 carats. The Giants were producing 150, enough for the players, the front office, and the owners’ families. More noteworthy to Murphy, the rings, according to the article, were going to be manufactured by E.A. Dion Inc., a family-owned jeweler in Attleboro, two towns south of Foxborough.

After dark on June 8, Murphy and a friend slinked behind the company’s office and workshop. The industrial park surrounding the white, one-story building was deserted, and it was so quiet they could hear cars pass on the highway a half-mile away. They wore their usual—black jumpsuits, black gloves, black booties over their shoes, and black masks with slits cut for their eyes—and carried crowbars, power saws, drills, and a cellphone jammer, a large metal box with four antennas.

They climbed onto the roof. Murphy found an outlet, plugged in the jammer, and turned it on. His accomplice walked the perimeter, trying to make calls with a burner cellphone as he went. No signal. Perfect.

Murphy leaned over the edge and cut a black wire coming from a telephone pole. Then he plugged in a drill and a power saw and started going at the roof itself. The grinding of metal on metal echoed through the industrial park. Once he completed a square hole, he jumped down onto a cage on the shop floor.

Inside the building, Murphy and his buddy found gold rings, gold necklaces, gold plates, boxes of gold beads, and drawers full of melted-down gold. Unable to crack the safe, they lifted it on a jack and pushed it through the loading dock onto their 24-foot box truck. Murphy was sweeping gold dust off the workstations when his accomplice came out of an office, his hands glittering with diamonds. There was a Super Bowl ring engraved “Strahan” and a few others that read “Manning.” By the time Murphy had finished loading up the box truck, he had more than $2 million of gold and jewelry and more than two dozen Super Bowl rings.

F--- ’em, he thought. They don’t deserve them.

In Lynn, a town of 90,000 filled with vinyl-sided houses and abandoned factories, burglary was a trade, passed down from criminal to criminal. “Lynn, Lynn, the city of sin / You’ll never come out the way you went in,” a popular rhyme went. In the 1970s and ’80s, when Murphy was growing up, local thieves specialized in prying open the doors to pharmacies at night and stealing pain pills to resell. “I didn’t think we were doing anything wrong—we’re from Lynn,” a burglar joked after a drugstore break-in, according to a police officer.

Murphy was introduced to burglary in the summer after eighth grade. One night his brother and some friends came home riding freshly stolen Yamaha dirt bikes. They told him if he wanted one, he’d have to sneak into the store and grab it for himself. He did. That Christmas, on a sleepover at his aunt’s house, a cousin helped him crack his first pharmacy.

Murphy’s father, Teddy, worked at the General Electric Co. jet engine plant that’s still the town’s biggest employer. But in the ’70s, when his son was in school, Teddy spent most of his free time at the Lynn Tap & Grill, where he sometimes brought his kid to bet on Pats games. This was before Bill Belichick, before Tom Brady—back when the Pats usually lost. Teddy never asked his son about his new source of cash, not even when he bought a midnight-blue Camaro. In high school, Murphy spent his loot on epic keggers and smoked as much weed as he wanted, which was a lot.

He first went to prison at age 17, after spinning out a stolen Corvette in a police chase and then, when the cops showed up at his parents’ house, fleeing on foot. It wasn’t as bad as he’d imagined. “Everybody’s scared about jail,” Murphy says during one of our many conversations over the past year. “I got there, and my whole neighborhood was there.”

Murphy got out after a few months and spent much of the ’80s and ’90s hanging with his buddies, cruising Lynn in his Camaro blasting Mötley Crüe, and burglarizing stores. He wanted to be the best the town had ever seen. He abstained from alcohol, mostly, and he didn’t use any of the painkillers he stole. But he loved lighting up a joint, sitting back in a chair, and thinking through his next caper.

Heist by heist, Murphy honed his technique. He practiced how to disable alarms, how to tie a climbing rope to rappel down from a roof, how to cut steel with a plasma torch, and how to crack a safe with an electromagnetic drill press. He was fanatical about not leaving evidence, concealing his fingerprints with gloves, his footprints with rubber booties. He once even sprinkled a crime scene with cigarette butts collected from a homeless shelter to confuse any attempt at DNA analysis.

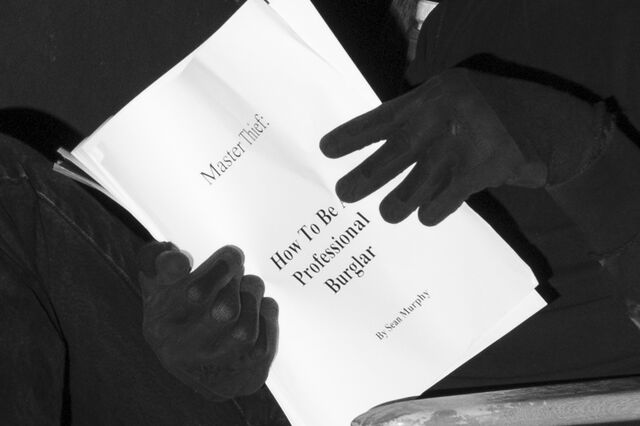

During a prison stint, he wrote an instruction manual titled Master Thief: How to Be a Professional Burglar, which he planned to sell to wannabes. Among his rules: Break in at nightfall on a Saturday, leave as the sun rises on Sunday. Cut the phone line, smash the alarm, and take the security tapes. Take half the score and let everyone else split the rest. And no weapons, because they lead to a longer prison sentence, and most places aren’t guarded at night anyway.

“I’m not one of those cowboy-type guys,” Murphy says. “The idea is, sneak in, do what you gotta do, and get out of there with nobody seeing you.”

Each time he got busted, Murphy saw it as a fluke, chalking up his failure to an unreliable accomplice or bad luck, even as he compiled a rap sheet of convictions on more than 80 counts. Somehow, prison time only increased his determination to be a criminal genius. During one seven-year stretch in the ’90s, he taught himself law so he could argue his arrests were improper. He also read widely on electronics; he was particularly impressed by a Popular Science article that explained how some alarm systems had cellular connections to police that could be defeated using an industrial-strength signal jammer. “An alarm is only as good as its ability to call for help,” he says.

Armed with a jammer, Murphy felt like he had superpowers. He could break into safes at leisure, free from fear that the authorities were coming. He coined a verb: to murph, meaning to cut communications lines and block wireless transmitters. He was so proud of his trick that he wrote to the president of Costco saying his “elite team of experts” had robbed its stores in “high-tech heists” and offering his services to stop other criminals. “You can now hire my security consulting firm to utilize our expertise,” Murphy wrote, signing his full name and address. Costco referred the letter to the FBI as a possible extortion attempt, but the feds didn’t pursue it.

By the early 2000s the Patriots were the best team in football, and Murphy was the undisputed top burglar in Lynn—the one other burglars turned to for loaner tools or legal advice. He started a furniture-moving company, Northshore Movers, which really did move people’s furniture, but also gave him a convenient excuse to keep a warehouse full of tools and trucks. Other than that, not much had changed. He was approaching middle age, but he still lived in the house where he’d grown up. He still watched the Pats with the same guys, drove the same muscle cars, listened to the same hair-metal music, and smoked weed every day. He also still threw keggers for high school kids.

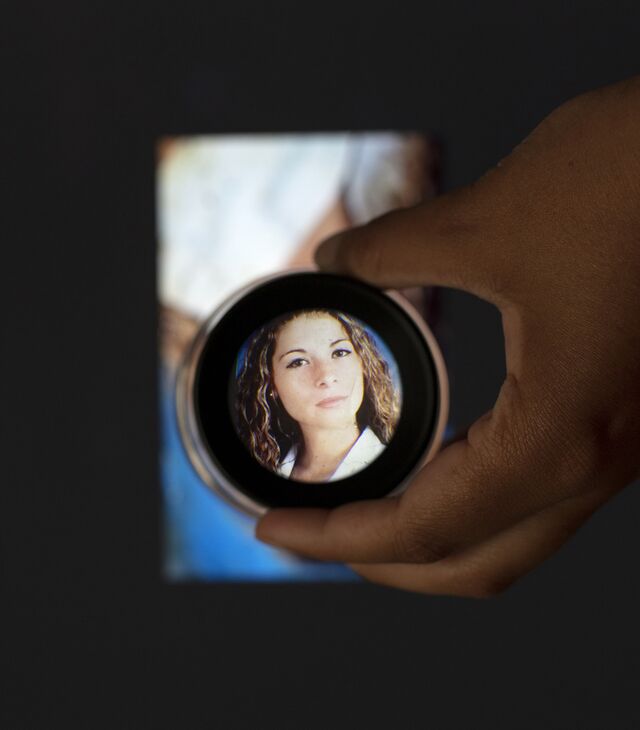

At one of them in 2003, he met Rikkile (pronounced “Ricky-Lee”) Brown, then a junior at Lynn English High School. She’d come to the party with some girls from her social studies class, who’d told her about an older guy who gave them cash to buy DV8 jeans that other kids couldn’t afford. A few years later, after meeting again by chance at a courthouse, they started dating.

Brown was 19, an aspiring radio news anchor with wavy brown hair. She also was addicted to prescription painkillers. Murphy, by then 42, kept a roll of cash and would give her some whenever she asked. “My life was always hard,” Brown says. “He made things very easy.”

Four or five other women Brown’s age had similar arrangements with Murphy. They settled into a bizarre imitation of domesticity: dinners out, group trips to the movies or a Kid Rock concert, vacations in the Bahamas and Hawaii. The women would alternate who spent the night with Murphy. They helped him run the moving company, and sometimes they’d sell stolen cosmetics for him at a flea market in neighboring Revere. When he was flush from a score, he bought all of them breast implants. “When you’re a young girl and you’re having whatever you want thrown at you, that’s tempting,” says another former girlfriend of Murphy’s, who was 20 when they met. “You grow up and you realize the creepiness. It was a very weird, twisted situation.”

Brown eventually moved in with Murphy. She says he called her the “Queen of the Castle” and talked about going straight and settling down with her—just as soon as he pulled off one last big job. But there was always one more. And though he told her he didn’t love the other girls, he kept looking for more of them. In August 2007, one came home from rehab with a 21-year-old friend. Her name was “J,” and she soon became Murphy’s favorite. (Bloomberg Businessweek is withholding J’s name to protect her privacy.) She moved in, and Murphy soon suspected her of stealing his electronics, to pawn them for drug money. Brown was baffled by Murphy’s patience with the new girl, especially because he told her J was just a friend. “It didn’t make sense to me,” Brown says. “Kick this bitch slut out!” Instead, he told Brown to move out, though they kept seeing each other.

As the 2007 Patriots crushed team after team, Murphy’s luck went cold, and he started to run low on cash. He was double-crossed by an accomplice who stole a large part of a 1.8 million-pill score. A few other burglaries were foiled when he or his tools were spotted ahead of time. After reading about the Super Bowl rings in the library, Murphy had high hopes. He told J that after this, they wouldn’t be poor anymore.

But then, a week before the robbery, he saw the Giants on TV: They were receiving their rings. “You can buy a lot of stuff, you can’t buy one of these,” Strahan said at an after-party at the Hawaiian Tropic Zone in Times Square. “You can’t take it away.”

Murphy decided to go through with the plan anyway, figuring that E.A. Dion, which he’d read had revenue of at least $10 million a year, would have other jewelry worth stealing. But as he discovered the night of the burglary, many of the Super Bowl rings hadn’t been distributed yet. Now they were his.

When Murphy got home, he spread the haul on his bed, where his girlfriends could admire it. Brown was on his good side that day, so he gave her one of the rings. J got the booby prize: a different ring intended for RadioShack employees with the store’s logo on it.

Murphy was thrilled when the burglary made the news. “A GIANT HEIST” was the New York Post headline. “Giant Jewel Heist Baffles FBI,” wrote the Boston Herald. Kate Mara, the House of Cards actor whose family co-owns the Giants, told New York magazine that her ring was among those missing. Some writers joked that the Patriots’ Belichick was the prime suspect. But the notoriety also meant that Murphy couldn’t sell the rings. He stashed his share in a safe deposit box and sold, traded, or gave away most of the rest of the E.A. Dion loot within a few months.

In October, Brown finally lost it over Murphy’s relationship with J. One day, she scratched the word “SLUT” onto the hood of one of his cars. A scuffle ensued. Brown said at the time that Murphy hit her, though she now says they shoved each other. In any event, he was charged with domestic assault and battery, but he was allowed to remain free. He figured he’d make up with Brown before the case reached trial.

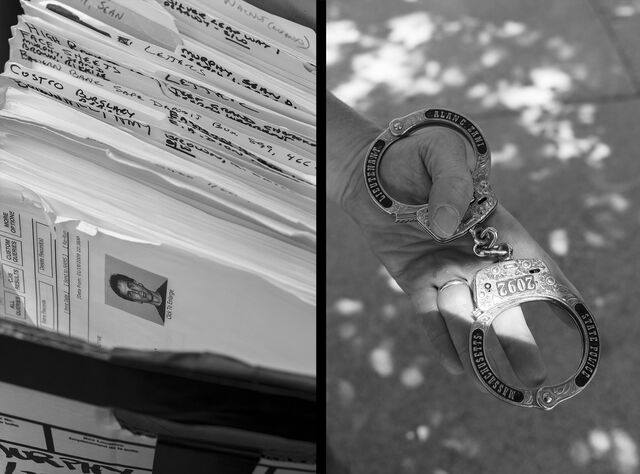

Lieutenant Al Zani had been after Murphy since about 1990, when he was an overachieving Massachusetts State Police officer assigned to Lynn. Raised in Danvers, a nicer suburb a few miles north, he was built like a fire hydrant, liked to box with other cops for fun, and believed he could personally make a dent in Lynn’s crime problem. He and two local detectives made a list of more than 135 professional burglars and associates in the city and set out to bust them all. He dubbed them “the Lynn Breakers.” Murphy topped the list.

Over the years, Zani earned a reputation in Lynn’s underworld as someone to avoid. He wasn’t the smartest officer, but he was the most dogged. Once, the story went, Zani jumped down from a hiding spot in a tree to make an arrest. Other times he posed as a drug addict or delivery driver.

In 2008, Zani was assigned to the FBI’s Boston bank robbery task force. It wasn’t as exciting as it sounded. Bulletproof barriers, dye packs, timer locks, and high-resolution security cameras had scared off all but the most desperate criminals. Most bank robberies were being committed by “note passers,” drug addicts who hand a piece of paper to a teller asking for money and walk out with a couple thousand dollars. Zani would wait for them to slip up. They usually did. When he found one at a homeless shelter near the scene of a crime, the man still had a note in his pocket that read “Count $3,000 no dye pack I have a gun.”

The E.A. Dion burglary had initially been investigated by local police. But after a couple months with few leads, the task force was called in to help. Zani says he knew right away that Murphy was the only burglar in the area who could pull off such a sophisticated break-in. He also knew Murphy was so cocky that he’d almost certainly hold on to the Super Bowl rings. “He’s a smart kid,” Zani says. “But he’s not smart enough.”

Zani and his partner, FBI agent Jason Costello, started driving by Murphy’s house and his moving company’s warehouse, but they didn’t see much. Zani called an old accomplice of Murphy’s, who wouldn’t talk. Then he found the domestic violence report. It listed Rikkile Brown as a victim and J as a witness. Costello paid a visit to Brown’s apartment. She wasn’t home, but he noticed her doormat, which read, “Come Back With a Warrant.”

Zani had more luck with J. She had an outstanding warrant for burglary, so he arranged to have her arrested. On Jan. 15, 2009, he and Costello approached her at the courthouse. They told her they wanted to talk about her boyfriend, Sean Murphy. They expected her to be unhelpful, but it turned out her relationship with Murphy had soured. When she later asked if Murphy would know it had been her who’d informed on him, Zani sheepishly admitted that he would. “Great,” J replied. “I want him to know it was me who did him.”

She said Murphy had bragged about his burglary skills and showed off his ninja suit and cellphone jammer. She also said Murphy had talked about doing something big that summer. Then she gave Zani what he needed: She complained that Murphy had given Brown a Super Bowl ring.

The next day, Zani went to the task force offices in downtown Boston to plan Murphy’s arrest. Unfortunately for Zani, no officers were stationed outside Murphy’s home that morning as he set off in a moving truck for Columbus, Ohio. And so no one was watching when he arrived at a squat, white-and-blue warehouse surrounded by a barbed wire fence in a corner of an industrial park. It was a Brink’s armored car depot. And if Murphy was right about how much money was inside, he was about to attempt the biggest cash heist in U.S. history.

Asked why he robbed banks, the famed bank robber Willie Sutton supposedly said, “Because that’s where the money is.” Credit cards, ATMs, and e-commerce mean that’s no longer true. A bank branch might hold as little as $50,000 to cover a week’s withdrawals. But a Brink’s depot is a different story, with enough cash in its vault to fill a dozen or more armored cars, each of which could supply several branches. Murphy had seen 40 trucks parked at the Columbus depot on a scouting trip, which he figured meant at least $20 million. That would have cleared the U.S. record: $18.9 million taken from a Dunbar Armored depot in Los Angeles in 1997. And, crucially for Murphy, all the workers who came in the morning left at closing time, suggesting it was unguarded overnight.

It was a Saturday, as usual, when Murphy cut through the fence behind the depot. He’d brought two accomplices: Rob Doucette, the weed dealer he’d watched the Super Bowl with, and Joe Morgan, a 26-year-old part-time car salesman who’d become Murphy’s right-hand man. Murphy climbed onto the roof, set up the jammer, and cut the phone lines. “The building’s been murphed,” he told Doucette. Then he sawed through the roof, dropped to the floor, and epoxied the front door shut so no one could surprise them. Morgan pulled their truck up to a shipping dock, and they unloaded an oxygen tank, an oxy-acetylene torch, and a 10-foot-long steel pipe packed with smaller rods.

These were the components of a thermal lance, a heavy-duty tool normally used to demolish bridges or decommission battleships. The mechanism is simple: Pump pure oxygen to the end of the long pipe, then use the smaller welder’s torch to light it. With enough oxygen, the fire can burn as hot as 8,000F—almost the same temperature as the surface of the sun. The lance consumes itself, melting down to a nub within a few minutes of cutting.

Murphy put on a welder’s mask and a leather jacket. With Morgan supporting the back end of the lance, he brought the welder’s torch to the tip and set off an explosion of sparks. The warehouse filled with smoke as Murphy touched the lance to the vault door, melting through it instantly. Molten steel dripped like lava, and the pipe burned toward Murphy’s hands as he traced a small hole. A square of steel hit the floor.

Murphy looked through the smoking hole. He’d cut too deep. The money was burning. He sent Morgan for a hose.

Murphy didn’t know it, but Brink’s had stuffed its vault in anticipation of a busy week. There was $54 million waiting to be delivered to banks, $12 million on its way to the Federal Reserve and $27 million for ATM refills—a total of $93 million. Some of the bags of money were just inches from the door.

The burning cash smelled horrible. Doucette started vomiting. Murphy rigged a fan he’d brought so it would draw smoke out through the ceiling. Once the hole had cooled down, Murphy strapped on a painting respirator and squeezed through, burning his nose on an edge. It was so tight his buddies had to push him in by his feet.

Murphy had grabbed only one cash brick when he started to feel lightheaded from the smoke. He realized that if he passed out, he’d probably be left to die. He wiggled back out into the warehouse, and the three took turns reaching through the hole and pulling out as much as they could. The bills that weren’t burnt were soggy from Morgan’s hose. They borrowed a forklift and loaded their truck with 5 tons of coins—$396,290 worth. At 8:45 a.m., with the fumes still suffocating, Murphy left. When the Brink’s guards arrived a half-hour later, smoldering bills were fluttering in the air.

After a stop at a hotel and a 12-hour drive back to Doucette’s house in Lynn, they dumped out the money and started counting. Murphy and his crew had stolen more than $1 million in cash. But the bills smelled terrible, and many were damaged. Doucette sprayed Febreze on them to try to cut the smell, but that didn’t do much. They tried putting some of the bills through a laundry machine, which only crumpled them into balls.

They still hadn’t dried and smoothed out all the money four days later when, just before sunrise, 19 police officers and FBI agents surrounded Murphy’s house, shined a spotlight into his bedroom, and stormed in to arrest him. Murphy was wearing only boxer briefs when they cuffed his hands behind his back. Another group followed Brown to a methadone clinic, pulled her over, and brought her in for interrogation. A third team searched Northshore Movers.

Costello tried to butter up Murphy. “For my money, you’re one of the top guys out there,” the agent told him. Murphy just smirked. The cops had no idea he’d just robbed Brink’s, and he was hoping they wouldn’t find out. Brown threw up during her interrogation, but she didn’t crack either.

At Murphy’s house, police found two safe deposit keys and traced them to a bank in nearby Saugus, where Zani found 27 Super Bowl rings. They also found paperwork from a cash-for-gold liquidator where Murphy had been selling the stock from E.A. Dion. The liquidator told them that another man, David Nassor, had been selling gold for Murphy. After Costello arrested Nassor, he told the FBI agent that he’d gone to Ohio to scout a Brink’s depot and that he believed Murphy had broken into it with Doucette and Morgan.

Costello decided to visit Doucette and bluff him. The agent told Doucette he knew all about the Brink’s burglary. “I’m not here to arrest you today, but we will be coming back for you,” Costello said. Within a day, Doucette agreed to cooperate, the agent says.

Murphy was held in prison, unable to raise the $3 million bail. After about a year, he was ready to make a deal. Given temporary immunity to negotiate a plea agreement, he confessed to everything. He gave tips about other burglars and even sat for a videotaped interview about his techniques for the FBI to show new agents. But the tips were too stale to be useful, Costello says, and the videotape was never used in training. (Murphy says this was intentional; he avoided giving the FBI anything it could use to charge anyone else.) The best deal prosecutors offered Murphy was about 10 years in prison for the Brink’s burglary if he pleaded guilty, then a trial—and likely more prison time—for E.A. Dion.

Murphy wasn’t about to accept that. His first lawyer quit after realizing Murphy wanted to try his luck in front of a jury. When his replacement told him to take the deal, Murphy decided to represent himself.

On Oct. 17, 2011, Murphy stood at a lectern in an Ohio courtroom dressed in a shirt and slacks from Men’s Wearhouse for the occasion, with a remote-controlled shock band around his calf to make sure he didn’t run away. He’d spent the night in his cell writing an opening statement. It was a tricky situation. Under plea bargaining rules, his confession couldn’t be used against him, unless he contradicted himself in court. That meant he couldn’t directly deny committing the crime. Doucette and Nassor had pleaded guilty and agreed to testify against him. (“We got caught because he gave a f---ing 20-year-old girl a Super Bowl ring,” Nassor says. “F--- him.”) And the prosecution had a copy of Master Thief, which had incriminating tips such as “be extremely careful when piercing the last layer of steel on the vault door.”

Murphy decided to argue that he was, more or less, a burglary professor who was being set up by his pupils. “Have many of you seen the new movie, The Town?” he asked the jury, referring to one of his favorite films. He told them that his hometown of Lynn was full of professional burglars, like Boston’s Charlestown neighborhood in the Ben Affleck movie. The prosecutor, Salvador Dominguez, just had the wrong guy, he argued.

“Sal’s playing a game that we all played when we were little kids, every single one of yous played it when you were a little kid—it is called tag,” Murphy said, sounding like Clarence Darrow as interpreted by Mark Wahlberg. “And unfortunately, I am it. But, ladies and gentlemen of the jury, by the time this trial is over, you are going to realize that I have tagged two other people, and I am not it.”

While questioning witnesses, Murphy referred to himself in the third person and seemed to get sidetracked by his favorite subjects. Over the course of a five-hour cross-examination, he went over Doucette’s muscle car collection, car by car, and asked him if the weed he sold was clumpy.

Murphy: Why don’t you just admit to the jury that you took Murphy’s professional burglary course?Doucette: I’ve only hung out with you, and we smoked weed. And you told me, because you like to run your mouth, about how everything is.

Murphy: So you expect the jury to believe that you traveled halfway across the country, used cell jammers, deactivated alarm systems, cut open vaults, stole over a million dollars, and this was your first burglary?

Doucette: You are very convincing and good at what you do, and you only needed a follower. So, yes.

The jury found Murphy guilty on all charges, and the judge sentenced him to 20 years in federal prison for the Brink’s job, reduced to 13 years on appeal. Doucette was sentenced to 27 months for his role, Nassor got three years, and Morgan 55 months. Brown was put on probation for receiving stolen property.

I wrote to Murphy last year. I’d read a little about his case and was curious if he was a Patriots fan like me and if he’d been out to avenge Brady’s loss. Over dozens of phone calls, he told me his story. He’d been dragging the E.A. Dion case out for a decade in state court, outlasting two prosecutors, and in November, I went to see him represent himself at a hearing.

Murphy shuffled into court in Fall River, Mass., his ankles and wrists chained together. Now 55, he seemed small, wearing a way-too-large striped dress shirt and slacks, with reading glasses on top of his thinning gray hair. He carried his legal papers in a clear plastic bag. Happy to have an audience, he turned and gave me a thumbs-up.

Toward the end of the hearing, Murphy huddled with the prosecutor and the judge in a corner of the courtroom. He told me later that he’d cut a deal that should see him released next year, but the prosecutor on the Brink’s case says he still has years left on that sentence.

Murphy has been in prison since 2009, long enough to watch the Patriots win three more Super Bowls, lose another to the Giants, and see Manning retire and Brady leave for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. He’s been inside so long that he’s never used an iPhone or Instagram. He still doesn’t mind prison. These days, he works as a block runner, collecting other inmates’ meal trays and taking out their garbage. To raise money to pay his property taxes, he sues the prison, whether for opening his mail or charging him to make copies, and reads newspapers to look for tainted products so that he can sue, claiming food poisoning.

Amazingly, this sometimes works. Murphy says he’s won about $10,000 from prisons in four settlements and $750 in a dispute over a bad batch of salami. “You fill your day up with a routine, and time just goes by,” he says.

Murphy is proud that “murphed” has been adopted into Lynn burglar slang and that treasure hunters search for gold in his old house. But he says he’s retired from crime. The only score he’s plotting now is how he’s going to get someone, preferably Ben Affleck, to turn Master Thief into a movie. It would be like The Town, only even more thrilling, he says. “I’m just as good, if not better, than them guys,” he says.

Murphy says he’s still got some of the Super Bowl rings, including the one with Strahan’s name on it. (The Giants say the stolen rings were for team staff, and Strahan’s never went missing.) Once he’s out, maybe he’ll slip it on his finger. He says he’d like to open a marijuana business now that it’s legal, or maybe become a security consultant, for real this time.

“There’s a lot of ways to make legitimate money out there,” he says. “I’m just going to keep my hand out of the illegal cookie jar now.”