I’m not sure there’s a more uneven body of work in contemporary television than that of ESPN Films, but sometimes the rollercoaster proves worth the ride. This Sunday, just a few weeks after the network finished airing its incoherent, bloated, and breathlessly hyped Michael Jordan advertisement The Last Dance, it will premiere Be Water, a nimble, nuanced, and at times even poetic documentary about martial arts legend Bruce Lee. Directed by Bao Nguyen, Be Water is one of the best entries in ESPN’s longstanding 30 for 30 documentary series, and a welcome reminder that the network is capable of producing terrific original content when it’s not under the thumb of those it’s covering.

Bruce Lee is, in many ways, a singular presence in popular culture. He is among the most famous action stars of all time, yet still something of a hazy figure. I would venture that almost every American has heard of Bruce Lee and can immediately conjure his image, but far fewer have actually seen one of his films, in part because there are so few of them. Lee starred in only four completed martial arts films in his lifetime, the last and most famous of which, Enter the Dragon, was released one month after his sudden death by cerebral edema in the summer of 1973. With the possible exception of James Dean, it’s difficult to think of another movie star who’s exerted such monumental influence in such a relatively slim body of work.

Be Water is an intimate film in both content and form. Instead of employing a voice-over narrator, the film relies entirely on interviews, many of which are with Lee’s surviving family, including his wife Linda, daughter Shannon, and brother Robert. (In a sickeningly tragic irony, Lee’s son, Brandon, was killed in 1993 in an on-set accident while filming The Crow, a movie poised to deliver him to the very Hollywood stardom that had eluded his father in life.) Nguyen also smartly eschews onscreen talking heads, letting his film’s testimonials play out in audible form over archival footage of Lee. Aside from assorted family members, those voices also include cultural critics Jeff Chang and Sam Ho, as well as Lee’s friends and collaborators, such as basketball great Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

Be Water is a somewhat unusual entry for the 30 for 30 series, since most people would first tend to think of Lee as a movie star rather than an athlete. The film corrects this, rightly insisting that for Lee, those two categories were completely intertwined. On top of being a naturally electric screen presence—in his youth, Lee had been one of the most successful child actors in the Hong Kong film industry—Lee was a truly groundbreaking martial artist who saw himself as a sort of global evangelist for Jeet Kune Do, the hybrid “fighting without fighting” philosophy that he created. At one point in the film, a moviegoer in Hong Kong likens Lee to Rudolf Nureyev, and there is indeed something acutely balletic to Lee’s physicality, the complete and total control over his own body and its breathtakingly dangerous extremities.

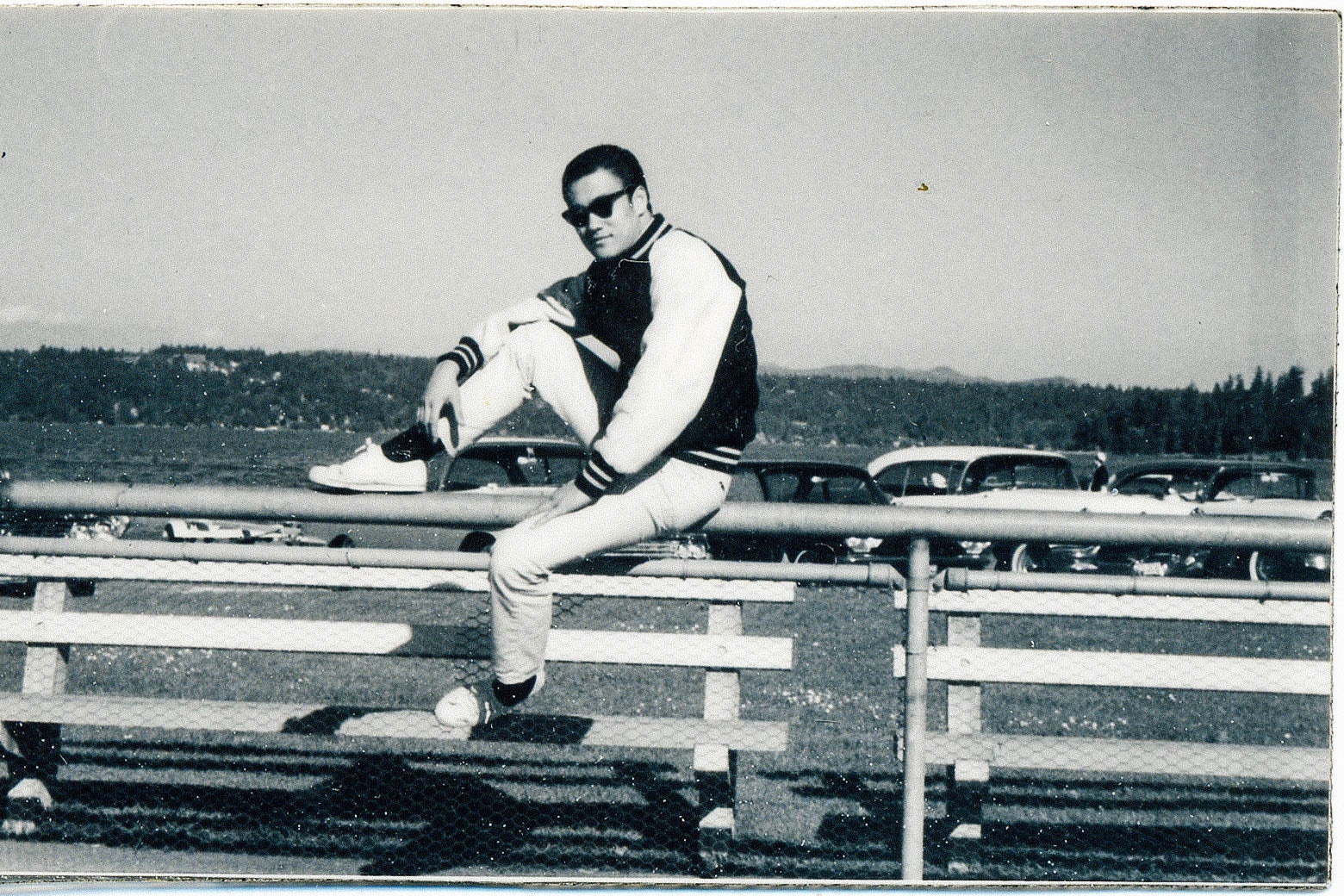

Lee was a truly transnational figure, in ways that sometimes haunted him. He was born in San Francisco but raised in Hong Kong. His father, Lee Hoi-chuen, was a Cantonese opera star, and his mother, Grace Ho, came from a wealthy Eurasian family. Lee was a child of privilege, raised in a context fraught with the turmoil and fissures of colonialism. He returned to the States at age 18, where he enrolled at the University of Washington, established a racially mixed group of friends and fell in love with a white American, Linda Emery, whom he would later marry.

Be Water is best when exploring the subject of race, a topic that it approaches with rare sensitivity for an ESPN production. In the mid-1960s, when Lee was trying to break into Hollywood, there were essentially no roles for Asian men that were not variations on yellowface caricatures, casting them as either the wacky comic relief or the sinister embodiment of otherness. (To emphasize the former, the film touches on Mickey Rooney’s appalling turn as Mr. Yunioshi in 1961’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s.) Lee had to fight tooth and nail to work outside of these constraints, and was still met with indignities at every turn. He relentlessly (and successfully) pressured producers to give Kato, his character in ABC’s The Green Hornet, more lines and screen time, but he remained woefully underpaid in comparison to his white co-stars. Crushingly, he lost out on the lead part in Kung Fu to David Carradine, despite the fact that many have contended that it was Lee himself who first brought the show’s concept to Warner Bros. (In Be Water we hear an executive feebly arguing that Lee was passed over because of his “accent,” a depressing feat of show-biz euphemization.)

In the early 1970s idea of an Asian American man—a demographic that had been relentlessly emasculated in American culture going back to the early 19th century—taking on anything resembling a conventional “hero” role was anathema to white Hollywood, but when Lee returned to Hong Kong for his first martial arts film, 1971’s The Big Boss, he became something of an overnight sensation. Fist of Fury and The Way of the Dragon soon followed in 1972; all three films shattered box office records. Enter the Dragon, co-produced by Warner Bros., was intended as Lee’s international breakthrough and succeeded as such, grossing $90 million worldwide (roughly half a billion in today’s dollars). By this time, Lee was dead, and had already crossed over into myth.

Be Water’s biggest shortcoming is that it fails to offer much insight into Lee as a person, one weakness it shares with The Last Dance, if little else. Some of the insights from Lee’s acquaintances are broad or verge on hagiography, and his daughter, who was only four years old when he died, openly acknowledges that she doesn’t remember much about him. But while The Last Dance sought to cover its dearth of revelation with puffed-up bluster, trying to pass off clichés as scoops, Be Water seems more at ease with the story it is able to tell. By the film’s end, we’re left with the sense that, like many great artists, Lee was and is to some degree fundamentally unknowable, a man myopically focused on perfecting a vision of himself that only he could truly see.

At one point in the documentary, Lee is described as “mid-Pacific,” a condition Chang likens to being suspended between continents and cultures. In life he was not fully at home in either the United States or in Hong Kong, where, even at the height of success, the sheer enormity of his stardom (along with his mixed-race family) set him apart. In death, Lee became a powerful symbol, the very bridge that, in life, he himself was never able to cross. Martial arts films exploded in popularity in the 1970s and 1980s, and soon his legacy was evident in everything from The Karate Kid to the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles to the music of Wu-Tang Clan. The film’s title refers to Lee’s famous exhortation to “be water”: “Formless, shapeless … water can flow, or it can crash.” But of course water is also what we drink, bathe in, and swim in. It’s all around us.