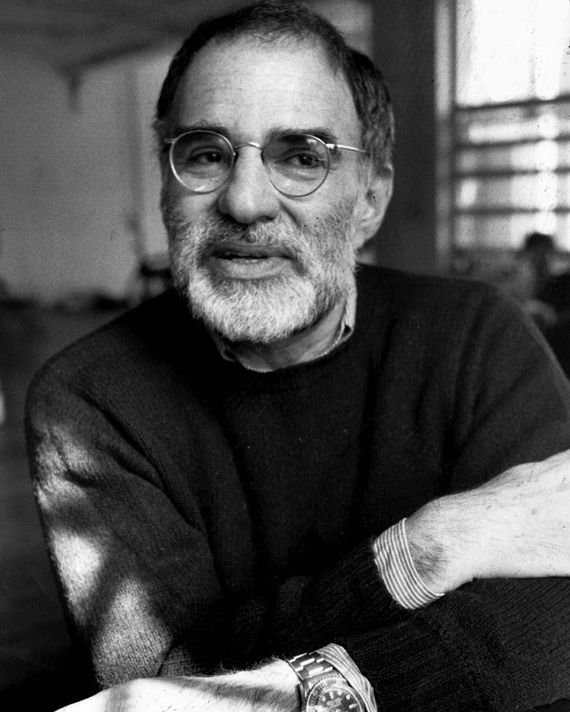

Larry Kramer died yesterday. The playwright, novelist, and implacable activist’s fury set the world on fire and into action during the early years of the AIDS epidemic. But for younger men, born well after a mysterious plague raged unchecked through the gay community, he could seem like a figure from history by the time of his death, even after the 2011 Broadway revival and Ryan Murphy’s 2014 all-star HBO version of his most famous play, The Normal Heart. He’s a part of the canon, and also in a way canonized, but for the current generation of gay men, he can seem like an abstract figure, important but distant even (or maybe especially) because of his anger. Kramer had different meanings to those who knew — and often fought with — him at the time and those who grew up benefiting from the causes he fought for. Jackson McHenry (born 1992) spoke with Mark Harris (born 1963):

Jackson McHenry: How did you first hear of Larry Kramer?

Mark Harris: I think I know the answer to that. It was when I was really young, being in a bookstore and suddenly seeing this word, “faggots,” on the cover of a paperback, which just roared out at me like some kind of, I don’t know what — threat or salute or challenge or something. I instantly wanted to pick it up and look at it, because it seemed like it was full of secrets that the other paperbacks on the rack did not know, but I was way too scared to. That was the first time I knew who he was, and it was well before The Normal Heart [which premiered at the Public Theater in 1985] or his big AIDS essay “1,112 and Counting” [which ran on the cover of the New York Native in 1983]. Probably the second time was seeing his name on the credits of Women in Love as a screenwriter. Novelist and screenwriter and scary provocateur who would call a novel Faggots. Those were my first exposures to Larry.

JM: It was so interesting to me to see, in all the obits that came out and everything, that he might have just sort of been a successful screenwriter or provocative novelist.

MH: There was an alternate life that Larry Kramer could have and might have had. He was a rising studio executive in the 1960s at Columbia, and really plugged in and kind of knew everyone, and then made this transition to screenwriting with Women in Love. Had AIDS not happened, it’s incredibly easy to imagine him as someone who would have spent his life in the movie business — maybe as a writer, maybe as a producer, maybe both. Maybe he would have written plays anyway. I can imagine that, even had that been the case, he would have pushed things forward for gay people, but the stakes would have been so much lower and his life would have been so much easier.

JM: And yet, even with Faggots, he was going for provocation straight off the bat, and that was 1978.

MH: That was a planted flag. I don’t think there’s any circumstance under which he would have been quiet. I believe that probably there was activism in him that would have come out no matter what, but AIDS just made the stakes so much higher. It cost him so much. That’s the other thing: He was really fighting for his life, metaphorically and literally.

JM: I think that’s what’s interesting for gay men of my generation. I know that he was, you said, a legendary figure of that era, and you’d sort of meet him through, or at least I did, reading The Normal Heart and seeing him as Ned Weeks — that it becomes abstracted in a way — but his real fury and anger and the cost of those fights that he was waging must have been so much to bear.

MH: Right. I didn’t see the first production of The Normal Heart in 1985 — I think I was in college. You read it, and you saw the HBO film version, so you know that it’s this lit stick of dynamite. It does this almost impossible thing: It was about what was happening right then. It’s so hard for art to do that. That’s not a thing that art generally does all that well because it takes a long time to create something and get it into a condition and a place where it can be seen, whether you’re talking about a play or a movie. You can understand the urgency of The Normal Heart not just from studying that moment, 1985 or ’86 — but in every scene of it, you feel the urgency. That’s incredibly unusual.

JM: Yeah. And it’s unusual that something like that would be able to be revived and be able to be not just a document of its era but something to still wrestle with. That’s a difficult accomplishment.

MH: Yeah. It’s a complicated and pretty fantastically powerful play. Part of its power, I think, is that it isn’t the AIDS play that would have been written five or 15 or 25 years later. It was a bulletin from that moment. I don’t think it was trying to be timeless; I think it was trying to be timely. In some ways, that probably makes it endure better. It’s this scream for people to pay attention.

JM: Yeah. I remember in college we had a big LGBT-U.S.-history survey course, and we didn’t read The Normal Heart. We read “1,112 and Counting,” but it was harsh, partially because the professor was just like, “The Normal Heart is too much to manage in a survey course.” It’s so much about Larry and about the crisis and everything that it sort of requires a lot more grappling than you could handle.

MH: How did you feel about “1,112 and Counting” when you read it?

JM: The thing I remember is the sort of relentlessness of it, the fury of it and the numbers. So much listing of numbers. It overwhelms you with statistics.

MH: And it can be repetitious. In a lot of his work, there’s a vibe of “never say in 200 words what you can say in 2,000.” It’s not a rage that burns itself out; it’s a rage that somehow keeps refilling its own tank. I think I read the essay fairly soon after it was first published, but I honestly don’t know. I think if I did, knowing myself at that age, it’s possible that I would have recoiled from the fury in it. I’m not sure.

JM: Yeah. And the sort of inwardly directed fury, which, I don’t know. When I first read it, you sort of feel distant from it. At least, for my generation, there’s the sense of “We have condoms, we have PrEP” — not that the epidemic has ended at all, but you’re more distant from being caught in the fear of the moment. I guess the — as we would say today — sex-negative aspect of it doesn’t register as hard.

MH: A lot of people could relate to this really intense screed saying, The government is failing us. The medical community is failing us. Our political leaders are failing us. Our scientists are failing us. But then, with his writing, it’s just as much that we are failing each other. And that’s a pivot that a lot of people find really hard to take. It’s very out of fashion now, and it was not exactly in fashion then. It’s always made him a difficult figure to contend with, that idea that, once his rage was turned on, it didn’t easily turn off.

JM: I remember reading it and thinking it was so incredible, in The Normal Heart, that he could have that distance from himself in the middle of that moment to make that character, to make Ned, so self-destructive. To be able to see that about himself.

MH: Right, right. There are ways in which The Normal Heart flatters Ned, but also ways in which it doesn’t. Those must’ve been really painful to write. I’m curious about whether for you, for people of your generation: Does it feel like Larry Kramer belonged to another era? Are there lessons about art and activism from how he lived and how he worked that you think resonate now? Or does he feel more like a historical figure to you?

JM: I think he definitely felt like a historical figure when I first knew of his existence — it was probably from high-school reading about The Normal Heart and reading about the existence of Faggots and watching And the Band Played On. Learning about his work in ACT UP was a way I, and I guess other privileged gay guys like me, got more radicalized in college or started to think about our political agency. The sense of infighting that people talk about falls away. You end up feeling a great debt to these people and all the people who are alive because of their work. There’s definitely a lot that I’ve taken for granted, and probably still do, but if you do the reading, that work seems so valuable.

MH: Sometimes when I hear younger gay men talk about Larry Kramer as an activist, I think that they’re talking about the side of his activism that goes down very easily, which is the part of him that was fighting against a world that was either indifferent or actively hostile to the plight of gay men. But if you only focus on that, it’s easy to forget how much shit he took for being “sex-negative” or a scold or someone who had never had fun himself and just didn’t want gay people to have fun or someone who was aligning himself with the worst kind of homophobes and saying, “You have to change your behavior.”

It took a really, really long time for Larry to be seen as a hero within the gay community. He was vilified by a lot of gay people, and that’s maybe a tougher part of his legacy to look at because it’s also a tough part of the history of the movement. “We have to change the way we behave” was such an explosive thing to say; just look at what we’re all going through now with the pandemic — it’s still an explosive thing to say we have to change the way we behave. It’s an explosive thing to say to anyone, and it was especially explosive to say to a community that was very few years into post-Stonewall openness and sexual liberation. It becomes easy to kill the messenger, and he did not mind being the messenger.

JM: Did you have many personal interactions with Larry? He and your husband, Tony Kushner, must have known each other.

MH: Yeah, they did. My interactions with Larry were not complicated. They were really lovely and pretty atypical, I think, because I interviewed him for my first book, which was about a period of movie history that coincided with the time that he was in the movie business. And I remember going to his apartment and being nervous, as you would be, because God knows I certainly knew that he didn’t suffer fools gladly. But to go to his apartment and to meet this very soft-spoken man in overalls, which he loved to wear with jewelry, who was more than happy to spend a lunchtime sharing great, funny, wicked, nasty, perceptive stories about the movie business …

He didn’t live the life he bargained for. I doubt very much he lived the life that he thought he was going to live when he was a college student at Yale in the 1950s. It seems just extraordinary to me that someone who is maybe not a natural firebrand — I don’t know his story well enough to know if he would have become an activist leader no matter what, but it seems to me that like the circumstances of the AIDS pandemic changed his life on a personal level and on a professional level and on a political level. The degree to which he rose to it and became this person who, in retrospect, seems like he was fated to be this leader of men is extraordinary. His follow-up to Normal Heart is called The Destiny of Me. But what if it wasn’t his destiny? If it wasn’t a destiny but just something he took on, that is even more incredible to me.

JM: And his history with Yale is fascinating. His love for it and then sense of betrayal — trying to get them to do the gay-studies department and having that fall apart — that he seems to have still harbored such anger over, is such an interesting thread in his life.

MH: Larry was Jewish, but he was a white man who went to Yale at a time when Yale was admitting Jews. He was of the generation that thought that kind of cut you out for leadership. I think he had respect for big venerable institutions and rage when he felt they didn’t live up to what he expected them to live up to. We talk so much now, when we’re talking about activism, about marginalized communities and people who grow up from a very young age understanding that they are on the fringes of something, and then they’re going to have to fight for everything they got.

But I don’t think that was his experience necessarily. Other than the terror and confusion that he may have felt initially realizing that he was gay, I think he was of a generation that expects to have access to the halls of power and the instruments of power. I don’t think he was uncomfortable with that at all, and I think it probably served him very well. I think that a sense of being entitled to do that — even though entitlement is now a very dirty word — is maybe more of an asset in activism than we sometimes give it credit for being.

JM: It’s old-fashioned, I guess we would say today, his understanding of gayness and gay men and his insistence that Abraham Lincoln was gay. It’s this idea of male gay identity as like a secret club, like you’re researching Greek love as a Victorian scholar at Oxford or something.

MH: The “Everyone was gay” version of history. We can leave that for another time. Even with him, it wasn’t, “My arguments deserve to be heard, so let’s hash it out.” I think it was, “My arguments deserve to win, so listen to me — I’m right.” I think in some ways he probably felt that he got into arguments only because there were people who were too stupid to hear what he was saying: There wouldn’t be any argument if you would just listen to me.

JM: Like, I figured it out — I have to lay it out for you.

MH: There’s no question that it cost him a great deal in terms of personal relationships. The list of people who admired Larry Kramer but stopped speaking to him at one point or another is very long. It’s a hard thing to wrestle with that side of him as an activist, the degree to which self-certainty is or is not an asset. I mean, that’s a really tough question.

JM: Yeah, and I think later in his life, that became more of a hindrance. I was also thinking about — for gay men my age and queer people in general — the infighting and the aspects of what was bruising and personal for him in those battles hasn’t remained as strongly in people’s memory. I feel like a lot of people could recognize the ACT UP slogans — the graphic design and all of that — with a sense of the value of what they accomplished. Larry Kramer was turned into an icon even before his death.

MH: And someone whose anger is in a way cuddly, which really does him a disservice. It also does a disservice to the complexities of that anger and how much anger costs you and the people around you. I don’t think he would ever have put it that simply or suggested that his anger hadn’t come with a very big cost. He was much smarter than that.

JM: What do you think he would’ve made over the subheadline the Times put on his obituary originally? About his “abusive” anger costing him.

MH: Yeah, I guess they’ve dialed it down to “confrontational” now. First of all, he would be, like, on page four of the most blistering letter to the editor they’d ever seen. And second, just as important, he would have known who to get it to. He would have sent it to five other people in case the person he wanted to get it to tried to bury it. That is a really important part of activism. And one that I don’t think you can fully pursue, unless you are reasonably comfortable with the idea of power.

JM: I wonder what it was like for him to see … it’s too easy to just compare AIDS and coronavirus, but to see another plague. In that interview in the Times, he talked about how he was working on another play about plagues. But I just want to know what was on his mind about now.

MH: He was 84, and he’d been in such frail health for a long time. Obviously, that was not a secret. Everything tried to kill him that could try, but it’s hard to believe that he’s not around. On a gay-theater-history level, it’s stunning and sad to me that we’ve lost Mart Crowley, Terrence McNally, and Larry Kramer in three months. As different as they all were as people, as different as their approaches were, that is just a gigantic swath of the history of gay American theater-making. Among so many losses, that’s a very big one that hopefully we’ll get time to process and room to process at some point.

JM: We lost so much of that generation, but to lose the people who bore witness to that loss themselves so heartbreaking, to not have even that second layer of knowing that moment.

MH: It’s also incredibly moving to me that he did not end up alone. That Larry was very loved and did not spend the last act of his life in isolation or anything like that. That he left behind a husband. That’s a meaningful thing and I think an advance that at one time he probably would not have imagined.

I’m curious, because I know you love theater and feel very connected to it and I know you care about the issues that Larry cared about. Do you want the art you see to be activist? Do you want to see more Normal Hearts?

JM: I do, but I think the thing that’s really hard is that you want them to be as good as The Normal Heart. You want it to be both activist and haranguing, but compelling and energetic and emotional, which is what’s so hard. Politically provocative theater can end up being boring.

MH: Anger in itself isn’t either a positive or a negative quality in art. You can write a really angry, really bad play.

JM: Recently, What the Constitution Means to Me was such an angry play in a lot of ways but was also compelling and a great performance and that kind of thing. Or Slave Play, which has a lot of unsettlement and fear and anger in it too, is also clever and winking and playing with you. But I think you do want it to feel alive. You want something that feels like a document of the moment.

MH: But when I think of What the Constitution Means to Me and of Slave Play, both of which I really love, I think of them both as plays that were perhaps to a degree written out of anger, but not as plays that were written in anger. They are like the incredibly lucid work of artists who were able to take the rage that they may have felt or that they may feel about any number of things, and do the work that artists do, which is process it into something that’s polished and surprising and personal and unexpected and thoughtful. Right?

But The Normal Heart feels like a play that was written out of anger and in anger. And usually that doesn’t work, but for The Normal Heart, it did. Usually that is not a great formula for writing an enduring play. But there’s no question in my mind that The Normal Heart is one that ten or 15 or 20 years from now could be staged and absolutely make the hairs on the back of your neck stand up.

JM: It has so much anger at the audience, at you in the audience. Almost like, “Why are you sitting here? Why are you not madder?” Which I would love to see.

MH: There are some plays now — I mean, there are certainly acclaimed plays that indict the audience to some degree. I mean, would you say Fairview?

JM: Yeah. And A Strange Loop, and Donja Love’s One in Two, which continued a lot of the rage about AIDS into its depiction of the epidemic among black gay men right now.

MH: The original production for The Normal Heart is something I think about. It’s one of those for which I wish I could travel back in time. God knows I don’t want to live in 1985 again, but to be in a theater when that was being performed in 1985 — I would like to know what that felt like. I really would.

JM: What were the people saying to each other or under their breath as they left the theater? That’s almost what I would love to know. What do they say as they’re walking out to the street?

MH: I saw Angels in America when it opened in 1993, which was long before I met Tony. And even though it was set seven years earlier, there were people with AIDS in the audience at any performance who were clearly very sick. And you absolutely felt like you were seeing a play about now. What shocks me, in retrospect, is that The Normal Heart is a play that seems to understand how much worse it was going to get. And I think that’s why Larry got sentimentalized in some ways as kind of an oracle, because he really did seem to see ahead in that play.

When I last saw The Normal Heart onstage, which I guess was the Broadway revival, I found that I had to remind myself of all of the things that people didn’t know yet about the course of this in 1985, about what had and hadn’t happened yet, because the play seemed to know it all. Usually, you get jolted back into history when you see an old play by coming face-to-face with what the play was oblivious about. That has not been my experience anytime I’ve seen The Normal Heart.