Aside from baby boomers and lovers of midcentury whimsy like myself, not many people remember Bye Bye Birdie. It’s a stage-then-movie musical from the early 1960s that you might have seen on the shelves at your local video store as a kid. Maybe you remember it being a plot point on Mad Men, or heard about in 2016 when NBC vowed to make it their next live musical (they still haven’t). But I’ve been listening to the soundtrack a lot lately. I bought a copy of the 1975 Original Broadway Cast rerelease a few years ago, an ostensibly ironic purchase that, if I’m honest, was always sincere. It was the first step in my acceptance that I actually, genuinely like musicals—not just the experience of seeing one in a darkened theater, but the actual score itself. Over-the-top as they are, soundtracks from stage productions bring me as much joy as the rock ’n’ roll I cover at my day job. And in the past few years, it has felt almost necessary to stop hiding my love of the cheesiest American art form and embrace my status as a lifelong theater nerd.

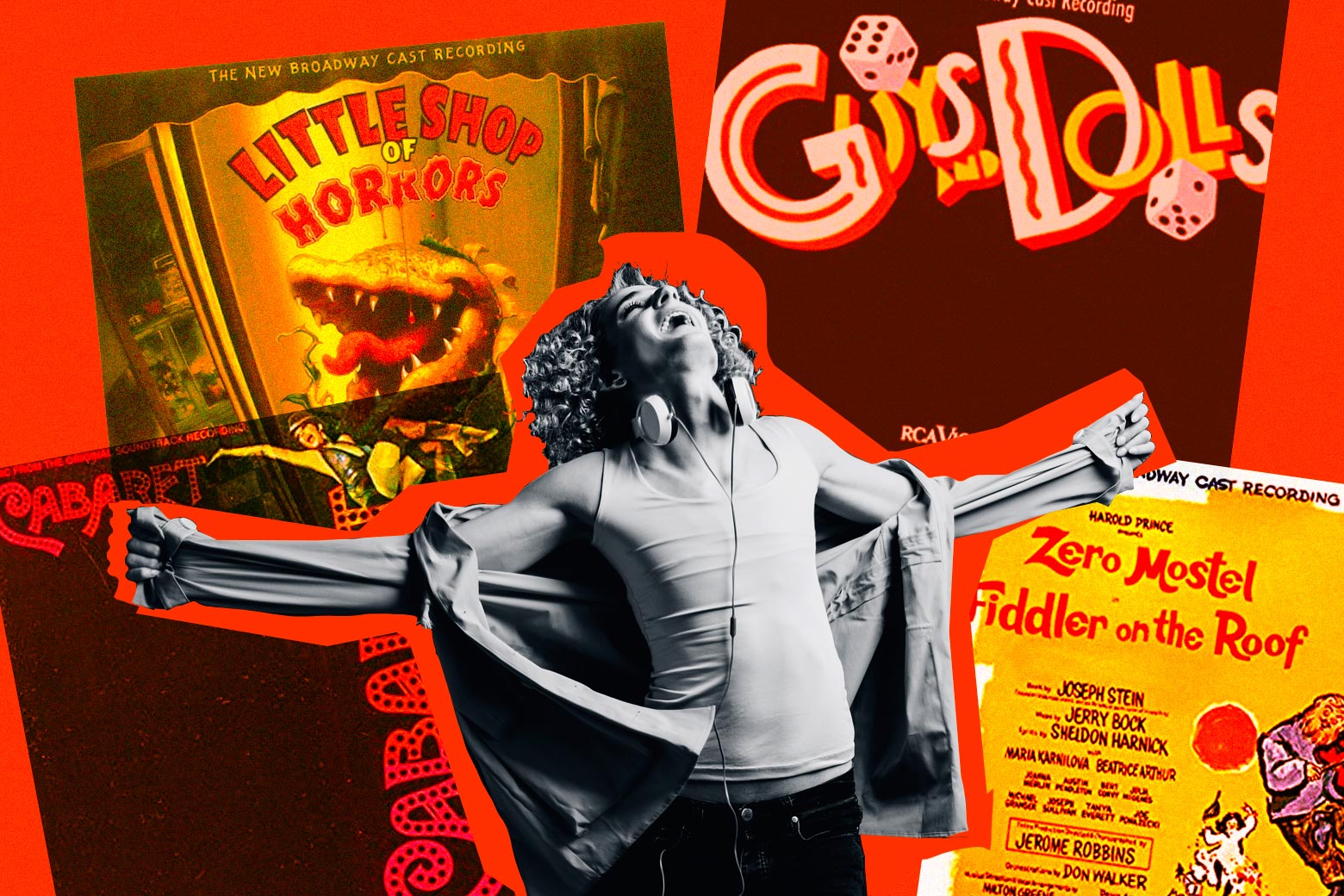

I love a long list of classic musicals: Cabaret, Little Shop of Horrors, Fiddler on the Roof, and many more. I like to call myself a “reformed theater kid”: I was active on school and community stages in my tween and teen years, but before that, I knew them through my immigrant family. (I’m ethnically Mexican but culturally white.) Both my grandparents crossed a border to settle in California and weathered the Depression and World War II in rapid succession (the deciding factor in my grandmother marrying my grandfather was that he had a stable job as a cab driver). They endured racist side-eyes from their white neighbors and made an effort to ditch any remaining Mexican culture they might have brought with them to the States in order to fit in. They filled their house with big-band music, American standards, and some popular soundtracks. As a result, I literally don’t know a single song in the Spanish language (aside from some snatches of Selena I’ve picked up over the years), but I do know “A Bushel and a Peck” from Guys and Dolls, because my grandmother used to sing it to me.

As an adult, I’ve try to keep my performing past under wraps. Being a theater nerd was never cool to begin with, but it’s worse to cling to memories of your time in the spotlight like a high school football star still shining up his trophies 20 years later. Polite society seems to find something sad about being nostalgic for the activities you loved in adolescence. But now that we’re in the midst of a worldwide pandemic, shame is no longer a concern of mine.

It seems a lot of other people are getting over any lingering self-consciousness surrounding show tunes, too. Over the past week, theater geeks everywhere have been breaking their long silence. Some are crowdsourcing recommendations on Twitter. Actors and enthusiasts are inviting students to sing their now-canceled solos for the masses via video. PBS knew exactly what we need for the long days of quarantine: a treasure trove of perennials like The Sound of Music, 42nd Street, and The King and I. And, perhaps most moving of all, infamous cinematic disaster Cats was released on iTunes for the good of the nation. If we can’t be together in a theater to take our mind off things, we’ll sing some light, fluffy songs at one another from a distance.

Sometimes, musicals soothe us because the music itself is like shooting cotton candy into a vein. But sometimes there’s an element of catharsis: While the classics are often the all-singing, all-dancing bursts of joy that give the musical genre it’s happy-go-lucky stereotype, more contemporary works can be complex, somber, and brimming with black humor. Fiddler on the Roof lays the horrors of displacement bare. Sweeney Todd sees people singing about feeding corpses to the public. Rent reflects the toll of the last great public health crisis in the United States. And as I have impressed upon my husband numerous times, Cabaret is not just another campy, flapper-focused, Fosse-choreograped vehicle about the onstage antics in a nightclub. These days, the theme of a carefree way of life being slowly chipped away at by world events is a little too real.

But even when they reflect troubled times, musicals offer a tantalizing escape from a dark reality. The music is, more often than not, bouncy and upbeat, and everything usually wraps up neatly by the end. They also seem to go mainstream when people need that the most: The Depression ushered in the first great wave of movie musicals, World War II and the handful of years after were the golden age of the American stage, and the genre went under an innovative overhaul in the Vietnam years with shows like Hair and Godspell. And though Hamilton, with its famously diverse cast, made its Broadway debut in 2015, its vision of a U.S. built by immigrant labor spread across the country as a rebuttal to a wave of white-nationalist fervor. It often feels glib to say that great tragedy inspires great art, as if the latter could ever make up for the former. There’s never a time when things aren’t tough to at least someone out there, but when ways of life start to be upended across the globe, the musical genre—especially the examples of it that are most well-known—acts as a communal comfort. But maybe the musical’s power to comfort in uncertain circumstances is why my grandparents loved them so much. And maybe that’s why the country has suddenly burst into song.