It’s Okay to Leave Your Headphones at Home

How one writer learned an accidental lesson in the joys of silence

A striking thing happened to me the day after Christmas while I was visiting home. In the middle of a long run on a grassy levee that walls off an untamed estuary from the rest of New Orleans, my phone died. The music blaring from my Bluetooth earbuds ceased with an impolite bloop and halted me mid-stride. Already sweating, I became even clammier at the thought of running multiple miles to get back home in dead, early-morning silence. No high-bpm jams from Travis Scott or the Pretenders to ward off boredom and propel my knees along. With no other options, I began the return leg cold.

A few moments passed, with no nearby sound but the rhythm of my footsteps and my labored breathing on a loop, and it hit me that this was the first time in weeks (or was it months?) that I had actually been alone with my thoughts for more than 12 minutes.

I live by myself in a studio in New York. But even when I’m home, I can’t help but watch something, text or read an email from someone, listen to some podcast, or put on some album. On the way to work, I listen to the news. At work, I’m scrolling, calling, clicking, meeting, editing—or reporting on policy and reacting to news. Once I’m “off” work, I head to drinks or dinner with my partner or friends. Shower, (maybe) read (probably for work), sneak in a bit more work, sleep, repeat.

I’ve forgotten what it’s like to be bored, but also what life is like without a static hum of interstitial stimuli in between live conversation. Twenty years on from the dot-com bubble, the internet has made access to knowledge and entertainment frictionless. Yet the web is now also creepily centripetal, making our ever-antsier lives warp and orbit more tightly around it. Reflecting on how humans have become too absorbed to enjoy analog existence itself is admittedly very 2016. But surely like many readers of those reflections, my tech itch didn’t feel acute then.

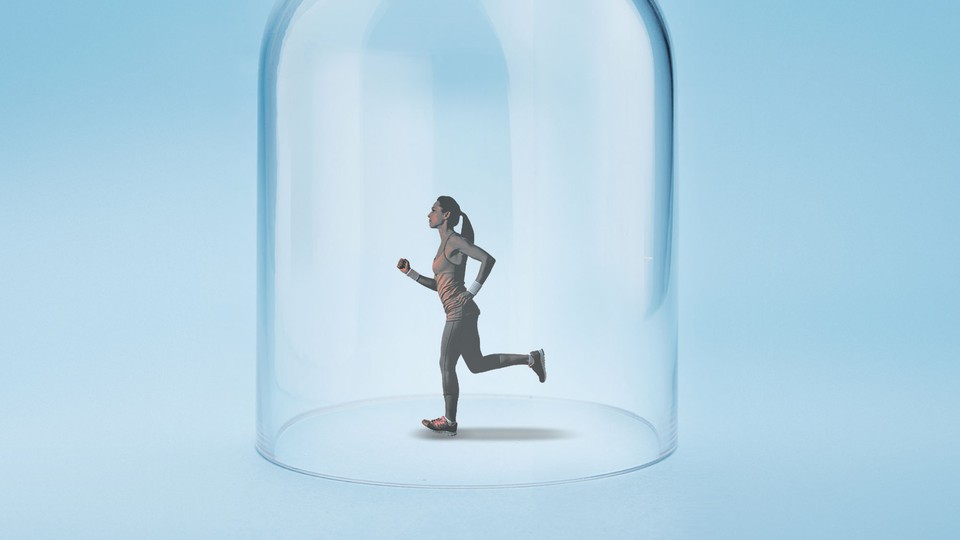

Now, along with countless people I know, my resting posture has become a neck craned and back hunched over a screen, fingers twitching across an endless well of info and images; chest slightly tightened. When solo—in bed, in an elevator, or almost anywhere in between—there always seems to be something more immediately rewarding to do (whether productive or dawdling in nature) than to be in our own heads. Better that than risk letting daily anxiety and existential panic set in.

By the end of that accidental silent jog over the holiday season, however, I was reminded of what clearing one’s mind must truly feel like: Things I suppressed or hadn’t given full reflection—like the appropriate guilt I felt for forgetting a promise to a friend or the warmth I still felt from a Christmas morning spent listening to B. B. King with my 89-year-old grandfather—had happily been processed or had mercifully floated away.

Better than the quotidian runner’s high I get when jogging with music, I felt reset. And I wondered whether this ancient practice of cardio in solitude—which was honestly a bit dull for the first few hundred steps—was, in fact, a key to easing postmodernity’s malaise. Long hailed as a stress release, much of exercising has been noisily swallowed back into the tech-laden productivity and self-help craze: how many steps, how many calories, how good compared with everyone else—on this app, in this gym, in this class. As The New Yorker’s Jia Tolentino and others have mournfully written, wasn’t all of this supposed to help?

For many, organized religion is, frankly, useless. Therapy isn’t for everyone. And I’m among those who can’t meditate, at least not well; the stillness it requires makes me only more aware of my own restlessness. So instead of patiently sitting with my thoughts, I’ve begun to run with them instead, a few times a week if I can, ears free of all input besides the ambient noise of the streetscape. No high-octane, borderline-embarrassing EDM to temporarily blast worries away nor any high-brow radio to distract me from distilling my own cultural opinions. Only heaving lungs, lurching limbs, and toxins being exorcised via sweat.

It’s true that it’s become harder to stay quite as excited about running miles three and four. Yet the rare, hushed stretches of mental isolation flush away petty gripes and reinforce what I love, which makes it an attractive Zen-like habit, if not exactly addictive. I’ve grown to leaving my earphones in my pocket on the subway (most times), scrolling less, and people watching more. And on weekends, I try to go on errands sans phone. Generally, I feel jauntier, more in tune.

That’s likely no coincidence: In recent years, groups of scientists have discovered that extended moments of quietude lead directly to increases in cognition and the regeneration of brain cells. Being in your head isn’t usually written about or spoken of in a positive context; probably because the phrase is typically a chastened explanation for appearing maladjusted in public. But even these godlike machines that we’ve created and surrendered ourselves to have to turn off and reboot in order to function.

I’m not fully rehabilitated. Sometimes acts of digital omission can feel forced even though they are, literally, natural. Convincing myself not to scratch that itch—or that the stranger at happy hour could be more fascinating than the Twitter thread in my pocket—is still a lively internal debate. I still play tug of war and fetch with Turtle, my 10-month-old puppy, and have to fight the urge to put on a podcast in the background to be a little more productive.

The other week, on some pleasantly normal night, I reached for my phone mid-tug after it zizzed. Turtle gave me a single, guileless, low-register woof. I couldn't help but laugh, and take the hint.