A Virginia man helped bilk the US Navy out of nearly $200,000 by setting up a sham company to sell the service nonexistent training devices, say federal prosecutors.

Michael Kitrel, 42, was charged this week with conspiracy to commit larceny of government money. His alleged crimes were part of a larger $2.7 million scheme involving two Navy lieutenants and a senior chief petty officer who are already serving punishments for their roles in the brazen operation.

“The potential damage from procurement fraud extends well beyond financial losses,” explains a 2018 report from the Department of Defense (pdf). “This crime poses a serious threat to the DoD’s ability to achieve its objectives and can undermine the safety and operational readiness of the warfighter.”

Between 2013 and 2017, the department gave more than 15 million contracts (pdf) to companies that had been indicted, fined, or convicted of fraud, valued at more than $334 billion, according to the DoD’s own data. It was only a slight improvement over the period between 2001 and 2010, when the department awarded more than $1.1 trillion worth of contracts (pdf) to companies that had been found guilty of fraud against the government. Some recent frauds, as first reported by Quartz, have included vendors selling the Navy Chinese-made ballistic vests and helmets that were labeled as having been manufactured in America, and shipping hundreds of counterfeit radio antennas to the Navy SEALs.

According to court filings, Kitrel was operating at the direction of Lt. Randolph “Kaz” Prince, who is mistakenly identified as “Rudolph” in charging documents related to the Kitrel case. (The US Attorney’s Office acknowledged the error and confirmed that it is the same person, but declined to comment further.) Prince, 46, was the supply officer for his Virginia Beach–based unit, Explosive Ordnance Disposal Training and Evaluation Unit 2 (EODTEU 2). He had the authority to make purchases for his unit, and could steer the orders wherever he chose. So Prince, who had an expensive gambling habit, hatched a plan to funnel some of that money into his own pocket.

To set the operation in motion, Prince approached Kitrel, a civilian, with an idea: If Kitrel established an LLC, Prince would send no-bid contracts his way. The LLC wouldn’t actually provide any product, however. Upon “delivery,” Prince, who was responsible for confirming receipt of all goods coming in to EODTEU 2, would sign phony packing slips indicating the phantom items had arrived. Prince and Kitrel would then split the proceeds between themselves.

But Kitrel had never set up a company before. He asked Lt. Courtney Cloman, a naval flight officer with experience operating an LLC, to help him start the business. (How Prince, Kitrel, and Cloman knew one another to begin with is not specified in court documents.)

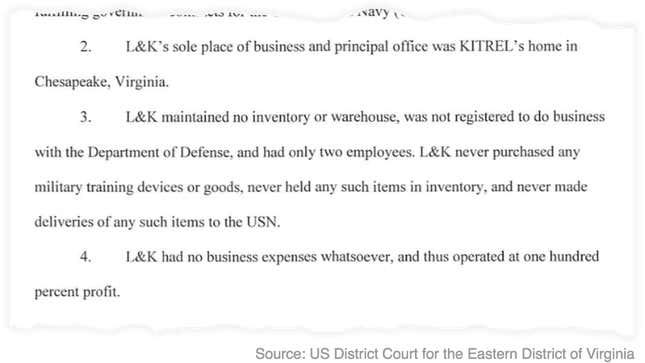

At the beginning of June 2014, with the help of Cloman, Kitrel registered a company he called L&K Technology and Logistics. Run out of Kitrel’s house in Chesapeake, Virginia, L&K “maintained no inventory or warehouse, was not registered to do business with the Department of Defense…never purchased any military training devices or goods, never held any such items in inventory, and never made deliveries of any such items to the USN,” a charging document explains. “L&K had no business expenses whatsoever, and thus operated at one hundred percent profit.”

Next, Prince drew up regular purchase orders for inert explosive devices—which are used for bomb-disposal training—that he steered to L&K. Kitrel or Cloman generated paperwork for each request under the pseudonym “Dave Freese,” which was then passed through an intermediary contractor identified in court documents only as “Firm V.”

“In total, the USN provided L&K approximately $190,386.00 despite receiving nothing in return,” from which Kitrel “personally obtained approximately $78,000.00 in fraud proceeds,” say filings in the case.

Prince divided up his unit’s purchases from L&K and (and from two other phony companies controlled by Cloman and a third co-conspirator) into multiple orders of less than $100,000. With an annual budget of more than $700 billion, it is extremely difficult for the service to maintain close oversight of smaller contracts like these, said Terence McKnight, a retired US Navy rear admiral who now works in the defense industry. Still, the swindle was so obvious that it was only a matter of time before the Prince crew was shut down.

In January 2019, Prince was sentenced to more than four years in federal prison. The following month, Cloman was sentenced to three years probation and ordered to pay restitution of $387,107.45.

“Jails are full of people who think they have the ‘perfect crime,’” McKnight told Quartz.

Kitrel’s lawyer, Waverly Winfield Jones, Jr., did not respond to a request for comment.

How they got caught

As often happens with such cases, it was a seemingly unrelated series of crimes that ultimately led to Prince and Co.

In the summer of 2015, about a year after Kitrel started L&K, a Navy sailor identified in court documents only as “JB” contacted the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS). He had received a letter of denial from Discover Financial Services regarding a loan he hadn’t applied for. Discover told JB that his name, address, and social security number had been used on the application. JB notified his Navy supervisor, senior chief petty officer Clayton Pressley III—who in 2007 received a Bronze Star for heroism—about the issue.

That January, another sailor under Pressley’s supervision, identified by prosecutors as “NH,” received a letter from Pioneer Services regarding late payments on a $10,000 loan he had taken out. But, NH had never taken out a loan with Pioneer.

It turned out that JB’s identity had also been used to obtain $14,000 in loans from Pioneer Services. A later transaction using a card linked to the loan account was made at a sandwich shop in Chesapeake, with the food being delivered to Clayton Pressley’s home address. And, according to bank investigators, Pressley’s name and phone number were also found on paperwork for a loan in JB’s name.

While pursuing identity theft and bank fraud charges against Pressley, who in 2017 was sentenced to 50 months in federal prison for those crimes, investigators learned he was involved in a much larger procurement fraud. This tip led them to Prince, Cloman, and Kitrel.

Like Kitrel, Pressley had also set up a number of front companies from which Prince, a onetime colleague of Pressley’s, ordered large quantities of nonexistent inert explosive training aids. And like Kitrel’s company L&K, Pressley’s companies maintained no inventory and never delivered anything to the Navy.

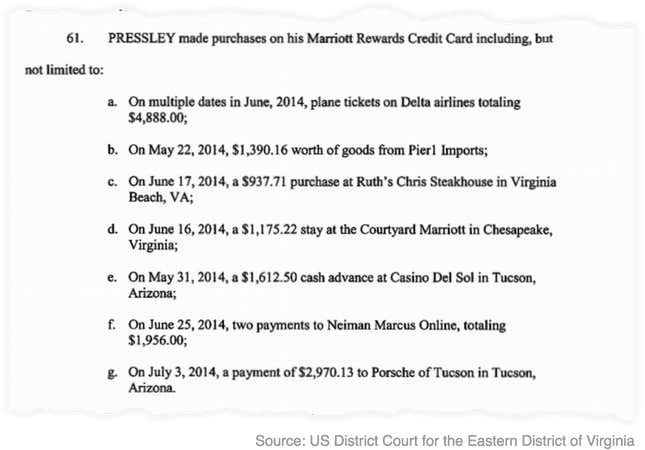

Pressley’s cut of the illicit proceeds came to $644,212.68, with which he bought, among other things, plane tickets, designer clothes, and meals at Ruth’s Chris Steak House.

In May 2018, while serving time for identity theft and bank fraud, Pressley was sentenced to two years in prison for his role in the procurement scheme.

“Inefficiency and stupidity”

Former CIA operative Robert Baer, who has deep knowledge of the relationship between the US government and private defense contractors, describes the business of military procurement as “the biggest transfer of wealth in American history, much worse than the robber barons.”

The way the Pentagon buys war matériel is “broken from the ground up,” Baer told Quartz.

“It’s the way the government works: inefficiency and stupidity,” he said. “Congress keeps giving DoD more and more money and they don’t know what to do with it. So you go get a contract and if you’re smart, you don’t get caught. And if you’re dumb like these guys, you get indicted.”

A scheme like the one perpetrated by Prince, Cloman, Pressley, and allegedly—at least for now—Kitrel, “throws up too many red flags” to be successful, said Cedric Leighton, a retired US Air Force colonel who now works as a private-sector risk consultant and specializes in insider threats.

“What’s interesting to me is how these people thought they could get away with this scheme,” Leighton told Quartz. “After all, any business you conduct with the government is subject to an audit, and if there’s no product to show for the money spent you’re in trouble…But, it looks like greed overcame good judgement.”

Kitrel is scheduled to appear in court on Jan. 27.