1.

Cindy Powell began to worry as soon as she pulled into the driveway of Dwight Gooden’s house in Port St. Lucie, Florida. Earlier that night, the 30-year-old architect had met the New York Mets’ most famous player at a nightclub called Banana Max. Gooden was hanging out with a pair of teammates, Vince Coleman and Daryl Boston. It wasn’t surprising that they’d approached her—she’d been on some dates with Mets pitcher David Cone, and they seemed to know that. So she’d danced with Boston and chatted with the guys as they shared some calamari. At some point, Coleman and Boston took off, leaving Gooden without a car. He needed to get home, he said. Powell offered him a ride.

Around 40 minutes later, in the early morning hours of March 30, 1991, they arrived at the house Gooden had rented for spring training, halfway down a street called Crystal Mist. Two other cars were in the driveway. Gooden said they belonged to his friends. Powell found that odd—she hadn’t realized that anyone else would be home. She had to pee, though, so she went inside. Boston and Coleman were in the living room, playing R.B.I. Baseball on Nintendo.

“My gut feeling said something is wrong here,” Powell would say, one year later, in a detailed statement to police. “Some bad karma or something; something did not feel right.” When the other Mets had left Banana Max, she recalled, they’d said they were going in a different direction. “You guys lied to me,” she remembered telling them. She said they laughed and offered her a beer.

Powell said she’d have a glass of water and that she’d leave right after. The guys asked her to sit and stay a while, she told police. She said thanks, but no; she had a long ride home.

At that point, Powell told investigators, Gooden took her wrists and began to tug her into his bedroom. “He kept saying, ‘I want to talk to you for a minute, I want to tell you something,’ ” she reported. “I kept saying, ‘What? Why?’ ”

First in a 30-page handwritten statement, and then again during a pair of taped interviews with the Port St. Lucie Police Department, Powell described twisting free of Gooden’s grasp and retreating toward the front door. She said that Boston was behind her, and that he asked “Where are you going?” as he herded her back toward Gooden. She told police that Coleman followed them into the bedroom, pulled the door shut, and turned out the light. She remembered that Coleman then pulled a suitcase over and sat on it, blocking the exit.

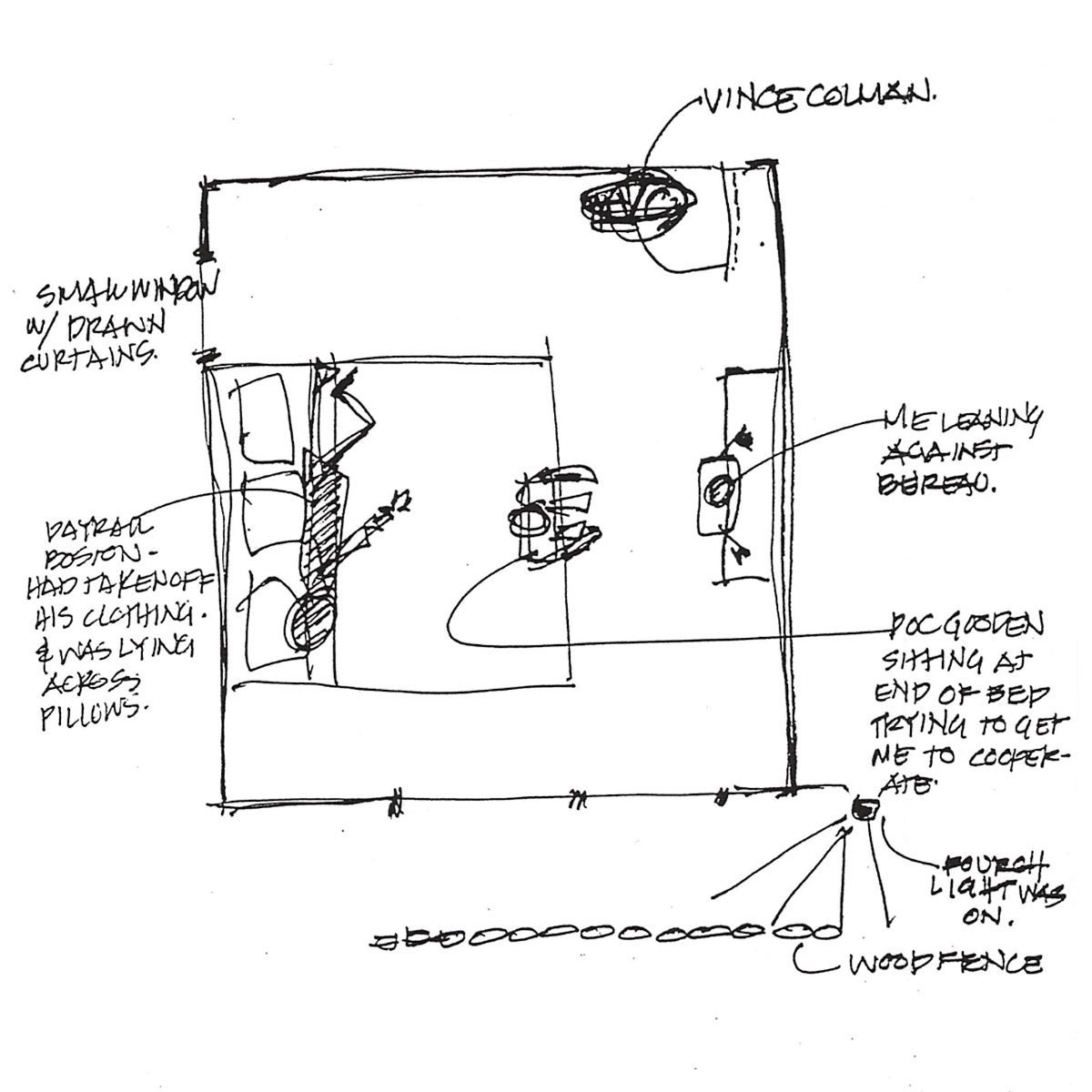

Powell told police a window-drape was partly open, that the room was cast in the dim reflection from a porch light. She said the men took off their clothes, and that Gooden sat at the foot of the bed. Boston laid himself across the pillows, naked. Coleman stayed where he was, between Powell and the door.

“You guys are scaring me,” she told them, according to her statements to police. She was leaning against a bureau, opposite the bed. “I’m not into this, I don’t know what you’re doing—you’re scaring me.”

“You should be flattered,” she said Boston told her. “Here we are, three black men, and we all want you.” According to her statements, Boston and Gooden began to kiss her on her neck and back. Then, she said, they bumped their heads together and began to laugh.

The rape lasted for two hours, Powell told police. “I just wanted them to do what the fuck they had to do and get off me,” she said. “Once I gave in, I felt no pain.”

Powell said that when it was over, Gooden offered her his autograph.

2.

New York’s celebration for the Mets, in the fall of 1986, was among the biggest in the city’s history. More than 2 million people came out for the ticker-tape parade; one group of fans squeezed so hard against a Modell’s store on Chambers Street that they smashed through its plate-glass window. “The Mets made us a small town with love and affection,” Mayor Ed Koch called out to the throngs. “Today we’re all one family.”

These champion Mets weren’t just local heroes. They were mega-stars on a national scale. Catcher Gary Carter was the face of Ivory soap. First baseman Keith Hernandez made the cover of GQ, and a few years later he took an acting gig on Seinfeld. Gooden, the pitching ace, was profiled by 60 Minutes, and his likeness was blown up on a five-story billboard at the Lincoln Tunnel entrance to Manhattan.

The 1986 Mets won a franchise-record 108 games during the regular season, then became baseball legends thanks to a pair of classic playoff comebacks: a 16-inning seesaw win over the Astros to take the National League pennant and a strike-away-from-elimination rally on the way to winning one of the greatest World Series ever played. I didn’t get to see Game 6 against the Red Sox on live TV. It was on too late, and I’d been sent to bed before Mookie Wilson hit the dribbler through poor Bill Buckner’s legs. I still remember laying rigid in the dark, guessing at the meaning of the cheers that drifted through my Manhattan bedroom window.

I was 8 years old when Dwight Gooden made his major-league debut in 1984. I was 9 when he won the Cy Young Award. And at 10, my favorite player and favorite team won the championship. That was all it took for Gooden and those Mets to become imprinted on my soul. They taught me how to be a sports fan—how to think of other people as representatives of me. I remember memorizing stats for every player on the team. I remember that my father sometimes watched the games with me, and that he’d say “Ooh, that’s a shot!” every time a Met hit the ball into the outfield. (That phrase became a hated jinx.) I remember reading Hernandez’s memoir and not knowing what it meant when he said he’d once paraded naked through the clubhouse, “flag at half-mast,” in front of female journalists; I had to ask my mother to explain. I remember that the Mets were the best team in the league, and good enough to win another title in 1988, but that we couldn’t make it happen. And I remember how, around the time Daryl Boston and Vince Coleman joined the roster in the early 1990s, the Mets got really bad. I remember that decline, the ugly tabloid headlines and embarrassments. I remember so much about the Mets, so many useless facts and anecdotes. But I did not remember the story of Cindy Powell.

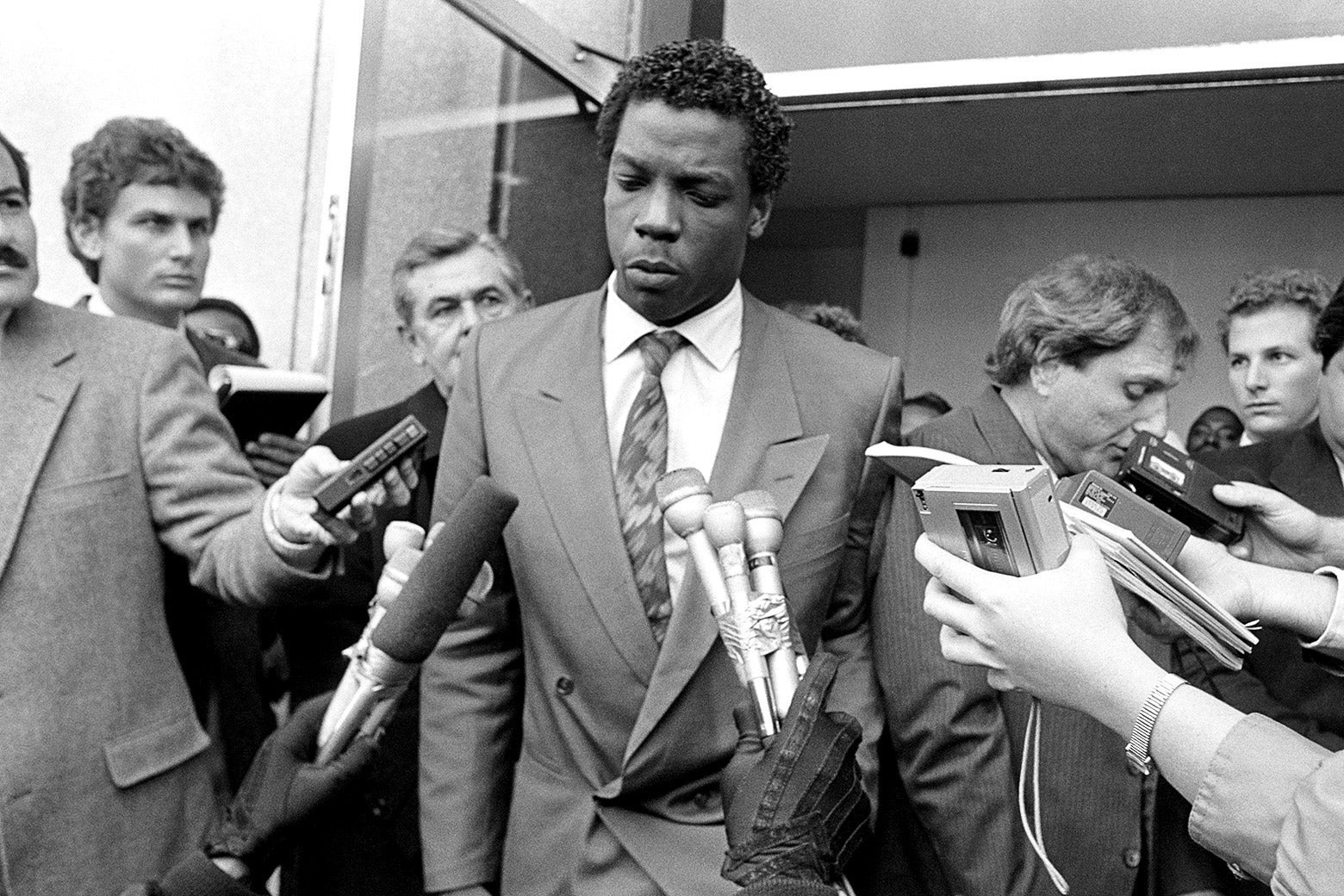

The alleged gang rape at spring training was an enormous scandal. The police in Port St. Lucie said they’d fielded 200 calls from reporters in the 24 hours after Gooden’s name had been linked to the case. The New York tabloids covered it exhaustively, as did sports-talk radio and shock-jock morning shows. The New York Times alone ran two dozen pieces on the investigation.

After four weeks of leering coverage, a Florida prosecutor announced that Dwight Gooden, Vince Coleman, and Daryl Boston would not be charged with any crimes. The odds of getting a conviction, he said, would be too low to warrant moving forward. “There are going to be people even eight, nine years from now, who are going to be bringing this up,” Gooden told the New York Daily News right after he’d been cleared. He was wrong. Two days later, Gooden took the mound in the Mets’ home opener: He pitched well, but lost. “NOT GOODENOUGH,” read the headline in the Daily News, with the story explaining that it was “his first appearance at Shea [Stadium] since rotator cuff surgery.” The rape inquiry wasn’t mentioned at all. Powell’s allegations had vanished. The story was over.

Last year, I came across a passing mention of the spring training rape case. When I looked more carefully, I found that Cindy Powell’s story, now forgotten, had unfolded in a context very similar to our own.

When Powell made her statement to police, she was stepping out alone against a venerated institution, one with deep support both where she lived and where she said she’d been attacked. At the same time, she was joining a cause much bigger than herself—an angry, hopeful push to identify and even redefine a plague of sexual violence against women. The year that Powell went to the police, 1992, was the Year of the Woman at the polls. It saw the dawn of third-wave feminism and the cresting of a furor over “date rape.” The Powell case made headlines not long after Anita Hill had testified in the Senate about the degradations she’d suffered in the workplace. Sexual harassment and assault were everywhere on prime-time television. L.A. Law even ran an episode about a baseball star accused of rape. (The player gets acquitted in the show, unjustly.)

In 1992, America was going through a reckoning: a moment when it seemed that rich, powerful, and well-connected men might, at last, be made to answer for abuse. And then, very quickly, it seemed that rich, powerful, and well-connected men might not be held to account at all.

Then, as now, there was a backlash: fear that men’s reputations could be too easily destroyed by idle claims of sex gone bad, angst about the spread of “victim culture,” and worries over the “polarizing discourse of political correctness.” Powell’s allegations against Gooden, Coleman, and Boston, coming when they did, got caught up in this broader storyline. And, like the movement itself, her case would founder.

Cindy Powell is a pseudonym. She died in 2012, never having expressed a willingness to associate her name publicly with the crime she said had been perpetrated against her. The New York papers and the national media kept her identity secret, even as she was made into a prop and her story was distorted and discredited.

Gooden and Coleman each told Slate that Powell’s allegations were entirely untrue. (Boston declined to comment for this story.) In her statements to police almost 30 years ago, Powell was unambiguous: She’d been raped by three members of the New York Mets, and she wanted them held to account for what they’d done.

3.

In the early 1990s, Cindy Powell was still living in the neighborhood where she grew up, in a prewar building on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The apartment in which she’d spent her childhood, with an older brother, had been filled with oddball pets—a rabbit, a monkey, a snake, a skunk—and furniture collected from the street. Their mother was a sometime journalist, a toy designer, and a former model who sold her homemade jewelry in Central Park. Their father was a playwright and a heavy drinker who’d philandered and decamped to Hollywood when the kids were young.

Both Powell and her brother were creative types, like their parents. He was an up-and-comer in the street art scene, a young talent whose reputation would be tied to those of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and Futura. She trained as an architect and had taken work designing hospitals. She also sold jewelry, as her mother had, mostly from a stall in Grand Central Station. That business started as a vision in a dream, of a necklace made from baubles held in glass: fragments of forgotten letters, cartographic scraps, faded rose petals, and silver charms.

Powell’s apartment was arranged like a personal museum: She had letterpress trays set up along the walls, their compartments filled with sewing buttons, doll heads, and whatever else she’d decided to collect. On the wall, she had a map of the world with pins in all the places that she’d been. Her friends describe her as a dreamer.

Powell liked to roller-skate, do aerobics, play Frisbee, and lift weights. She was always working out, and would sometimes challenge men to arm-wrestle. She could make her abdominal muscles undulate so it looked like they were rolling under her skin. When the first Equinox Fitness Club opened in 1991, management put a statue of a rock climber in the front. Powell had been the model.

Cindy Powell had blue eyes, an upturned nose, and “waist-length, butterscotch hair,” according to a story in the New York Post. She was festive, outgoing, the sort of person who made friends easily—on the street, in bars, while waiting on the unemployment line, wherever. She was just a bit taller than 5-foot-3 and weighed 105 pounds.

Powell had inherited a house near the Mets’ training camp in Florida, but she wasn’t much of a baseball fan herself, and it hadn’t been her idea to hang around the team. A fellow artist, Brenda, was the one who really loved the Mets, and who suggested they go to Florida to see some games. (Brenda is also a pseudonym, to protect her privacy.) The first player they got to know, in early March 1991, was David Cone. Brenda was the one who asked for his autograph. The pitcher chatted with both women for a bit, then Ron Darling joined the conversation.

“I was, like, really connecting with Dave at the ballpark,” Brenda would tell police. She and Powell accepted an invitation to hang out with Cone and Darling. They barbecued at Cone’s house—Darling made potato salad—and watched porn on the VCR. At one point, Brenda went for a skinny-dip in the pool. She and Cone had sex in the Jacuzzi. Later, Brenda explained to investigators, she had sex with Darling. Then Powell and Cone had sex. Everything was consensual. Everyone had a good time.

Cone was Brenda’s favorite player, but she said that she’d been just as pumped about the rendezvous with Darling. “This [was] my big chance,” she’d tell the Port St. Lucie police. “When we left that night, I was, like, screaming in the car, saying, ‘Pinch me, I know I’m dreaming!’ ”

Powell and Brenda met up with Cone again a few days later, and they all did Woo Woo shots at a nightclub called Coco Bay. A few other Mets were there, among them Daryl Boston. That night, both Powell and Brenda left the nightclub with Cone and stayed over at the pitcher’s house.

Brenda told police that Powell didn’t care for female competition, and the two of them soon returned to New York City. At the end of March, Powell went back to the house in Florida. Brenda had wanted to come along, but Powell brushed her off. Her mother would be there, too, she said, and there wouldn’t be space for guests.

4.

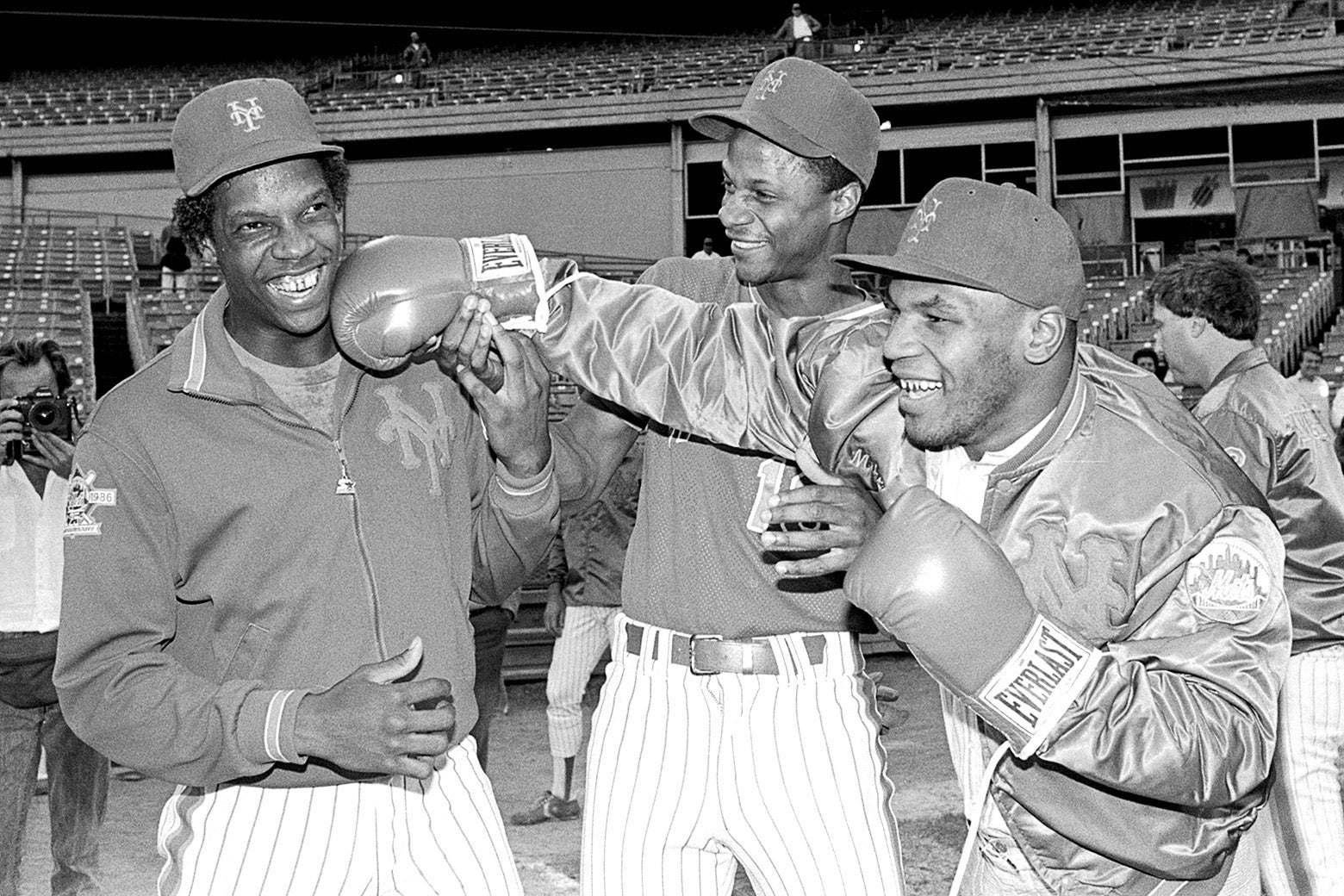

The 1986 Mets weren’t just baseball’s most famous and successful team. They were its meanest, too: the bullies of the league, known for their bragging and their brawls. “We’re going to drink all their alcohol, screw all their women, and kick their asses on the field,” the players would call out as a battle cry when they landed in a rival’s city. And then they’d do just that.

The Mets’ assholery—their clubhouse pranks and barroom mayhem—has been folded into lore. “As big a bunch of dicks as the ’86 Mets were, they were really lovable,” says Jeff Pearlman, author of The Bad Guys Won, a 2004 remembrance of the team’s title-winning season. “Yeah, they were gross and childish and whatever, but there was something really unique and special about [them].” That’s the thesis of his book and a tenet of nostalgia for my generation of fans. “There will never be another team like the ’86 Mets and it is sad,” Pearlman wrote in the preface to his book’s reissue. “In an era of corporate synergy and political correctness, baseball today lacks the fire and panache of yesteryear.”

Indeed, “those jackanapes Mets,” as the New Yorker’s Roger Angell called them, have long been celebrated for treating baseball as a kind of never-ending fraternity hazing. In Doc & Darryl, Judd Apatow and Michael Bonfiglio’s 2016 documentary about Gooden and fellow superstar Darryl Strawberry, Jon Stewart said of the ’86 team’s clowning ways: “Caligula is in the corner, like, ‘Whoa, guys, settle down.’ ” Yet the ugliest aspects of these escapades—the lawsuits and arrests, the times when raunchiness turned into abuse—have mostly been airbrushed out of their story.

The Mets were at their worst with women. In The Bad Guys Won, Pearlman claims that Gooden and Strawberry exposed their genitals to flight attendants on a team plane ride, inviting the women to “lick this and lick that.” “Strawberry and Gooden were just horrible guys on that flight—absolutely terrible human beings when they drank,” an unnamed airline staffer told Pearlman. “There could have been sexual harassment suits all over the place.” There was also the charter the team took back to New York after beating the Astros for the pennant in 1986. “We got blind drunk,” wrote Strawberry in one of his memoirs. “We snorted cocaine in the restrooms. We groped the flight attendants. We groped our wives. We shouted and howled. We threw our dinners at each other. We broke a lot of things. We threw up.” When they landed at the airport, Pearlman writes, the players and their wives were wrecked, their clothes half-off and vomit-stained.

These shenanigans, like most of what went on behind the scenes that season, were barely covered at the time. The Daily News soft-pedaled the post-pennant blowout with an item headlined “Mets’ flight of fun.” The players’ wives were “the life of the party on the plane trip home,” that story said; they’d danced and clapped as they sang, “Let’s hear it for the boys.”

Reporters also didn’t shed much light on the troubles brewing with Dwight Gooden. The pitcher’s downward spiral began in the hours after the Mets won Game 7 of the 1986 World Series. Years later, he’d admit that he spent that night in a housing project on Long Island, doing lines of coke and shots of vodka with a group of people that he barely knew. The next day, Gooden tried to sleep off the bender while his teammates rode up Broadway to City Hall in the ticker-tape parade.

Five months later, he failed a drug test for cocaine, and the first stories of his downfall broke. (He’d fail further tests in the years to come.) Gooden missed two months of the 1987 season while he did an inpatient stint at the Smithers Center for Alcohol and Drug Treatment.

Strawberry, too, would eventually check in to Smithers. After Game 2 of the 1986 National League Championship Series, Strawberry returned to his hotel room, drunk, and found that his wife Lisa had chained the door. Strawberry flew into a rage. When Lisa relented and opened the door, he admitted in his 2009 memoir Straw, he broke her nose with the heel of his hand. According to Mike Lupica and William Goldman’s book Wait Till Next Year, the beat writers joked that Lisa “should have told Darryl she was left-handed. Everybody knows he can’t hit lefties.”

More incidents of domestic violence followed. In 1990, Strawberry was arrested but wasn’t charged for punching Lisa and putting a gun to her head. In 1993, he was again arrested, this time for punching the woman who’d become his second wife. “Charisse, don’t ask me why, forgave me and refused to press charges,” he wrote in that 2009 autobiography.

Several of Strawberry’s Mets teammates would also get arrested for abusing women when their playing days were over. In 2005, Gooden pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor after being arrested for punching his girlfriend in the face. In 2011, three-time All-Star Lenny Dykstra’s former housekeeper accused him of forcing her to perform oral sex. Dykstra denied it—“This is a maid. That’s not even worth commenting on,” he said—and prosecutors decided not to file charges, saying there wasn’t enough evidence that the oral sex was forced. A year later, Dykstra went to jail after pleading no contest to charges of lewd conduct and assault with a deadly weapon; he’d recruited women for a job as his personal assistant via Craigslist, then stripped naked and demanded massages when they came in for interviews. When one of these women refused, he held a knife to her throat. Longtime Mets second baseman Wally Backman was arrested in 2001 for allegedly threatening to kill his wife; Backman denied that allegation and ultimately pleaded guilty to misdemeanor harassment. Backman was arrested again in August 2019 after allegedly pushing his girlfriend into a wall; that case is still ongoing, and Backman’s attorney says the allegations are “baseless and completely without merit.”

The Mets’ rosters from 1986 to 1991 would feature six players who’d be investigated for rape or sexual assault. All would deny wrongdoing, and none would be charged. One more Met from this era, pitcher Julio Machado, would be found guilty of killing a 23-year-old woman in Venezuela by shooting her in the head.

“We were a magnificent team,” pitcher Bob Ojeda said in an interview for Matthew Silverman’s 2016 book One-Year Dynasty. “The problem was we were out of control.”

5.

For the Mets of the 1980s and 1990s, as for many other baseball teams, sex was a sport. Trysts would happen after games, or before games started, or while games were going on. “If you’re talking about the number of guys who get a little head in the back of the bullpen during the course of the season, you’re talking about a pretty large number,” David Cone told beat writers Bob Klapisch and John Harper in The Worst Team Money Could Buy, a remembrance of the Mets’ 1992 campaign. That book lays out the team’s lexicon for sexual conquest. Ugly women were known as “mullions.” “Gamers” were women on the hunt for sex, while women who were small but fit were known as “spinners.” When a player “beat it up,” it meant he’d just had terrific sex.

It’s hard to know whether womanizing got more pronounced during the 1980s—or simply more transparent. At any rate, knowledge of the groupie scene in baseball would become mainstream by decade’s end, thanks to the Oscar-nominated film Bull Durham. Written by a former minor-leaguer, the movie starts with a monologue from its sexpot hero, Annie Savoy. “I’d never sleep with a player hitting under .250 … unless he had a lot of RBIs or was a great glove man up the middle,” she says, spritzing her bosom with perfume.

Almost all baseball groupies were white, according to a 1998 paper by anthropologists George Gmelch and Patricia M. San Antonio. Most were working class or lower-middle class and most had never gone to college. These women “enhance their seductiveness by wearing revealing clothes and ‘big hair,’ ” reported Gmelch and San Antonio, who conducted 15 interviews with groupies during the early 1990s, and another 105 with players. The women would move in pairs or threes, rather than alone, because it made it easier to meet athletes, and because it gave them “some measure of safety.”

A 1992 Associated Press story hinted at certain dangers of the scene. One woman said that she’d met a player at his hotel, expecting a night out. “He was just real pushy and aggressive,” she said. “Let’s put it this way. He had no intention of taking me out to dinner. I had to get very loud and bitchy to get out of there.” Another woman, whom the article described as “pretty if it weren’t for the hardness around her mouth and the bitterness in her eyes,” said she went out with an unnamed Mets minor-leaguer and his friend, and ended up getting taken to a hangar in a boatyard. She had only vague memories of having sex. “I couldn’t remember if I had a choice about it or not,” she said, explaining that she wouldn’t call it rape “because I was drunk.”

Stories from this time include just as many notes of caution for the players. A Newsweek article quotes one team employee as saying that groupies “are out for one thing only, and that’s to get money from a ballplayer.” Gmelch and San Antonio said that most teams asked the FBI to give lectures on groupie “scams.” A lawman would lay out this scenario: A girl takes a guy back to his room and then suggests they play some bondage games. Once he’s naked and tied up, a “co-conspirator” comes in with a camera so they can blackmail him.

Regardless of whether anyone ever perpetrated this particular scam, when men in baseball, or around it, evaluated the groupie scene, they figured that the athletes were the clearest targets for predation. “There is never a shortage of women,” Roger Angell wrote in his 2001 book about David Cone, A Pitcher’s Story. “All the players, right down to the coaches, are looked upon—except by children and out-of-it parents and geezer fans—as sexual animals and fair game.”

Writers and team employees suggest that the Mets of the 1980s and 1990s attracted a disproportionate share of groupies. In The Worst Team Money Could Buy, Klapisich and Harper described the “easy sex to be had in the bars” for any Met who wanted it. “Nobody showed up with more different women on his arm than the Mayor,” Klapisch and Harper continued, referring to Daryl Boston. “He didn’t discriminate, either: Black and single, Boston squired women of all races around town, and usually in style.”

“At night, we’d go out drinking and looking for women, and women would go out drinking and looking for Mets,” Gooden wrote in his 2013 autobiography. This is how he summed up the nightlife around training camp in Port St. Lucie: “The hookups were never hard to come by.”

6.

At home in New York City, Cindy Powell had her mind on David Cone. A friend she met around that time later told police that he saw Powell searching through the phone book, looking for a place that sold chocolate baseballs. “She wanted to buy [Cone] a little present,” the friend said. “I guess he had a bad game or something.”

About a week later, she let Cone know that she was back in Florida. He said his family was in town and he wouldn’t have time to get together. She tried again on Friday, March 29, 1991, but he said he was going out to dinner with his sister that night. Although Powell’s mother was in Florida with her, she told Cone that she didn’t feel like staying home. She might head to Banana Max, she said, the club right near her house.

Daryl Boston, Vince Coleman, and Dwight Gooden seemed drunk when they first approached her at the bar, Powell told police. She didn’t know Coleman and Gooden, but she remembered having seen Boston before. He remembered her, too—Powell said in her written statement that Boston blurted out Cone’s name at one point to get a rise out of her. Later, she said, the Mets claimed to be astounded that a white girl was willing to hang out with them. “That’s ridiculous,” Powell said she told the players. “I’ve lived in New York all my life and you can’t be prejudiced in New York.”

When she got to Gooden’s house, Powell wondered if her sense of dread—the “bad karma” that she felt—might be a sign of racial bias. “I was mad at myself for feeling prejudice,” she told police. It freaked her out to find Boston and Coleman in the living room, she said, but “I thought these ‘bad vibes’ were due to the fact that they were all black and I was white.”

Gooden forced himself on her twice, she told police, while she pressed against his shoulders with both hands. Boston and Coleman allegedly took turns coercing her into oral sex.

She recalled that when it was over, all three men left the room. Powell felt like she was moving very slowly. She looked around and decided she would straighten up the bed. Before she left the house, she said, she kissed Boston and Coleman goodnight.

For a while, she drove around in a daze. She got home after 3 a.m., then climbed into the bed she was sharing with her mother. “Did you have a good time?” her mother asked.

“Yeah, I did—but I drove Doc Gooden home, and then I kind of got lost,” she remembered saying.

She spent the next night with Cone. “I just wanted him to hold me and I didn’t understand why,” she told police. A few days later, she and Cone met up again. She brought him an Easter basket and helped him pack up some luggage to be shipped to New York. She stayed the night. On April 1, she dropped by the ballpark to watch Cone pitch his final spring training game, and proffered a half-wave from the bleachers to the men she’d later say had attacked her. In one of her interviews with investigators, she recalled crossing paths with Boston when the game was over. She thought she remembered him saying, “Mum’s the word.” She told police that she was pretty sure she repeated the phrase back to him.

Powell met another Mets player that afternoon, the outfielder Darren Reed. The two chatted for a while, and shared a drink, on the patio outside of Reed’s hotel. They exchanged contact information before she left for the airport.

It wasn’t until a few days after she got back to New York, in the middle of a conversation with a close friend, that Powell first came to think of herself as a victim. “I didn’t want to believe it,” she told police. “I was sitting there, and I turned to [my friend] and I said, ‘You know, I was raped.’ ”

At her friend’s urging, Powell spoke to the Port St. Lucie police. She refused to give them her name, or phone number, or the names of her attackers. “She was vague, very vague,” an investigator said. She did not file a report.

Early in the morning on April 4, Powell tried calling Cone but couldn’t reach him. Then she called Ron Darling, whom she’d met alongside Cone a month earlier. “Oh, my God. Oh, sweetheart. I can’t believe that,” she said Darling told her when she explained what had happened at Gooden’s house. “You’ve been in denial, haven’t you? You’ve got to do something.”

She replied: “I can’t, I’m scared.”

Darling promised he would have Cone get back to her, but she never heard from either of them again. In a later statement to police, Darling acknowledged that he’d talked to Powell and that she’d said “something bad had happened” involving sex with Gooden, Boston, and Coleman. He said that he hadn’t encouraged her to take any particular action, and that it wasn’t clear to him from their conversation whether she was claiming that she’d been raped. (When reached for comment on this story, Darling said he stands by that statement and has nothing more to add.)

A few days later, Powell called Darren Reed. He’d just been traded to the Montreal Expos, and she figured it might be easier to talk to him since he was no longer teammates with the men she said had attacked her. She told police that Reed seemed concerned when he heard her story and suggested that she tell someone—maybe the Mets’ manager.

Powell’s stepfather, a former police officer, suggested that she keep the outfit she’d been wearing on the night of the attack, which she said was stained with Gooden’s semen. She put that outfit—a long-sleeved, white cotton dress with a blue floral print—into a white bag. And then she waited.

7.

David Cone knew, in April 1991, that his teammates had been accused of rape. Ron Darling had passed along Cindy Powell’s message. But Cone chose not to get involved. “I really didn’t know what to do,” he later told police. “I just decided to wait and see what would happen, to see if she would go to the police with these allegations.”

Over the next 12 months, the Mets pitcher would himself be accused of sexual misconduct multiple times. In September 1991, three women filed a lawsuit against the pitcher, saying he’d confronted them when they were sitting in the stands at Shea Stadium in Queens and threatened to kill them. They also sued the team for $1.5 million, alleging that the Mets provided inadequate security at the stadium and failed to protect them from Cone. In a subsequent filing, the plaintiffs claimed that Cone had also exposed himself without consent on two occasions.

One of those incidents allegedly took place in the Shea Stadium bullpen, where one of the women said Cone had masturbated after inviting her and a friend behind a partition. (That friend, who was not a party to the lawsuit, backed up this claim to a reporter. “Anyone who’s even close to [Cone] knows about it,” she told the New York Post, which did not reveal her name. “Everyone has a dark side. We all do. His dark side has come to light.”) The other incident was said to have occurred in a hotel room; Cone allegedly entered after asking to borrow a towel, then proceeded to masturbate in front of two of the plaintiffs.

In his court filings, Cone would say that his confrontation with the women in the stands “did not contain or imply any threat of physical injury.” And in 1993, a judge would reject both masturbation claims, citing New York’s statute of limitations for cases of inflicted emotional distress. The New York Mets and the plaintiffs would reach a confidential settlement in September 1996. In his recent memoir, Cone admits only to calling the women “groupies.” He goes on to say that while he “wasn’t an angel,” he “definitely didn’t perform any weird sex act in the bullpen.”

Less than two weeks after those women filed the lawsuit, Cone faced a graver accusation: A woman in her early 20s told police in Philadelphia that he’d raped her. According to an interview she gave to the New York Daily News, Cone had invited her up to his hotel room and asked her for a back rub. She agreed, massaging him “from the waist up” until he flipped over and asked for a blowjob. She refused.

Then, she said, he forced oral sex on her and raped her. “I told him to stop. … He ignored me,” she told the Daily News, showing the reporter what she said were bite marks and bruises on her neck and breasts. She’d gone to the police early the next morning and was taken to the hospital.

Cone denied everything. “That’s a complete fabrication,” he told Frank Cashen, the Mets’ general manager. Cashen suggested that Cone sit out the last game of season. “Frank, you’ve got to let me pitch,” Cone said. He went on to have the best game of his life—better, by some metrics, than his 1999 perfect game. He allowed three hits, walked one batter, and struck out 19. “It was the most bizarre day of my whole life,” Cone would later tell the Daily News’ Mike Lupica. “I spent the whole day with one eye on the hitter and one eye on the tunnel, wondering if the police could actually show up in the middle of a game and arrest me.”

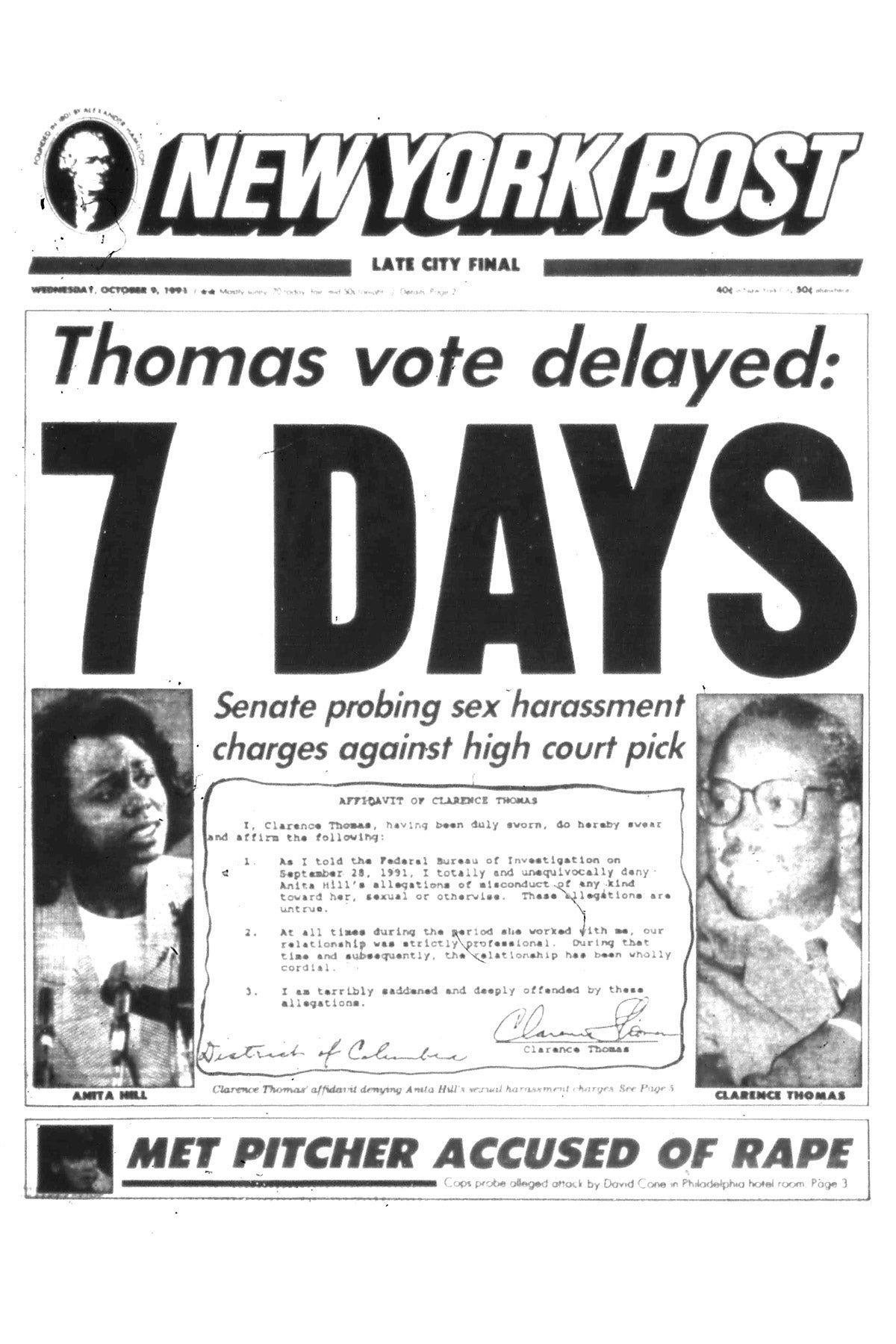

The story hit the tabloids three days later. A banner stretched across the front page of the New York Post: “MET PITCHER ACCUSED OF RAPE.” Above it was a headline about the other big story of the week, Anita Hill’s claims about Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas. Hill had gone public on the same day that Cone’s accuser went to the police. On Oct. 6, 1991, NPR aired an interview in which Hill described Thomas’ “very ugly and intimidating” behavior—including talking with her during work lunches about pornographic films involving bestiality, group sex, and rape.

A round of hearings to address Hill’s claims began on Oct. 11. Thomas called the coverage of her accusations “a national disgrace” and “a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks.” Pennsylvania Sen. Arlen Specter described Hill’s testimony as “flat-out perjury” and the “product of fantasy.”

That same day, news came out of Philadelphia that the rape investigation against Cone had been dropped. The woman’s “allegations were in conflict with other evidence we were able to obtain from witnesses and other sources,” a police spokesperson announced. Cone’s lawyer told the Post that the accuser had “admitted to at least one person that she fabricated the allegation to extract money from David.” He suggested that she be prosecuted for filing a false police report.

Cone’s accuser wasn’t identified in the press, and I’ve been unable to learn her identity. At the time, she suggested that the Philadelphia Police Department’s sex crimes unit had mishandled her case. “At the beginning I thought they were sympathetic, but they don’t seem to think I’m upset,” she told the Daily News just before the investigation was dropped. “One lieutenant told me, ‘I think you’re immature,’ that I shouldn’t be out by myself, and that I brought the whole thing on myself.”

About six weeks after the alleged incident with Cone, the head of the sex crimes unit was reassigned for publicly expressing doubts about a different woman’s story of sexual assault. Years later, in 1999, the Philadelphia Inquirer published an exposé showing that “the accounts of an unusual number of women victims” had been rejected by Philadelphia police. One investigator said that he’d learned to be suspicious of women who reported sex crimes. “Half the girls that came in, they were lying,” he later told the Inquirer. He even had a nickname for the office: “the Lying Bitches Unit.”

In the end it was Cone, not the woman he’d allegedly assaulted, who would gain the public’s sympathy. “I turned out to be the victim here,” he told Lupica on Oct. 25, 1991, a few days after Clarence Thomas was sworn in as a Supreme Court justice. “I found out firsthand how vulnerable you can be if someone wants to set you up. … And if she was out to trash my good name, she did it.”

Lupica opined that Cone “has always been one of the best of the Mets … somebody who stands in front of his locker, even when is in the middle of a controversy, and tells you the truth.”

Cone has said consistently that he never harmed or threatened anyone in connection with any of these cases. “First of all, I’m not a raper. Second of all, I’m not a pervert,” he told New York Magazine in 1999, adding that his “name was completely cleared.” He repeated those assertions (using slightly different words) in his 2019 memoir. In an email, Cone’s lawyer told Slate, “We simply see no point in commenting upon any of these matters, most of which are unfortunate, and all of which took place more than a quarter of a century ago.”

8.

Cindy Powell was having crying spells. She couldn’t sleep.

At a rooftop barbecue in June 1991, she told some guys she knew from her neighborhood what had allegedly happened to her at Gooden’s house. She also told them about the cotton dress. The guys advised her to get therapy before she took things any further. It would be best, they said, if she could “get her head straight first.”

Powell wasn’t sure if she ever wanted to come forward. She was uncertain, in part, because of another incident in Florida, one that happened the same night that Powell said she was attacked.

That Friday in West Palm Beach, at a swanky bar just seven miles down the road from where Powell met the Mets, a 29-year-old woman was hanging out with a medical student named William Kennedy Smith. Smith was with his uncle Ted, the senator from Massachusetts, and his cousin Patrick, who was in the Rhode Island House of Representatives. Later in the evening, the woman drove over to the Kennedy family compound. Smith invited her to go for a walk on the beach.

The next day, the woman went to the police. She said she’d tried to leave, but Smith tackled her and forced her into having sex. She tried to push him off, she said, and he told her, “Stop it, bitch.”

Powell was back in New York City when this story broke. Within a couple days, the woman’s name—Patricia Bowman—showed up in the newspaper. On April 17, 1991, the New York Times ran a detailed story on Bowman’s past, noting that she’d had a child out of wedlock, that she was known to have “a little wild streak,” that her driver’s license had been suspended on multiple occasions, and that “she liked to drink and have fun.”

As Smith’s trial date approached, more details about Bowman emerged: She’d been abused as a child; she’d had abortions; she’d used cocaine; she wore provocative underwear; she was, per Patrick Kennedy, “a Fatal Attraction type.” Meanwhile, prosecutors were barred from using testimony from three other women who’d come forward to say that Smith had attacked them, too, in similar ways. Several months later, Spy magazine published a dozen more accounts from women who said Smith had assaulted them, or tried to. In total, he would have 16 accusers. Smith’s lawyer dismissed these as “a lot of copycat claims.”

On Nov. 13, 1991, when Smith’s trial was about to start, Cindy Powell called the Port St. Lucie police a second time. Now she gave her name, but still balked at identifying her alleged attackers. Powell’s therapist would later tell police that the publicity around the Smith case had frightened her patient.

A few days later, the Times ran an op-ed by Katie Roiphe, then an unknown writer just out of Harvard College, with the headline “Date Rape Hysteria.” The culture of crying victimhood had gotten out of hand, Roiphe declared. “While real women get battered, while real mothers need day care, certain feminists are busy turning rape into fiction.”

At the end of that same month, the former Met Kevin Mitchell was arrested on suspicion of rape, battery, and false imprisonment. Mitchell was accused of inviting an acquaintance to his house, then dragging her into his bedroom and attacking her. The case was dropped soon after his arrest, though, because the alleged victim didn’t want to move forward; her lawyer said she “did not want to be put through the wringer” of testifying in a criminal case against a sports celebrity. Mitchell denied that he’d committed forcible rape, and his attorney told reporters that he was “personally satisfied that Kevin did not commit a crime.”

In the meantime, Powell struggled. She’d started therapy in October, trying to understand why she’d acted as she had at Gooden’s house. What had led her to tidy up his bed, she wondered, and to offer goodnight kisses to the Mets? She’d later say this was a way to “normalize the situation”—to protect herself from feeling violated.

One boyfriend from this period remembered how preoccupied she was with the incident in Florida. “It wasn’t going away,” he later told police. “She was constantly, in her mind, trying to figure out what she was going to do about it.” In another statement to police, a female friend—a successful indie rock musician—said Powell had started crying on a date after seeing “this huge billboard with Doc Gooden’s face on it.”

Smith’s trial began on Dec. 2, and 10 days later it was done. Powell watched on TV—“she was glued to [it],” the musician friend would tell police—and saw Bowman testify, and then be cross-examined, with a blue dot covering her face. It took the jury about an hour to reach its verdict: not guilty. Bowman gave an interview to ABC’s Diane Sawyer afterward without the blue dot. She chose to make a public statement, she said, because she was “terrified” that rape victims “will not report because of what’s happened to me.”

Powell’s friend told police that the William Kennedy Smith verdict had a chilling effect on both her and Powell. “We looked at each other and we said, ‘See, you just … you can’t do it,’ ” the friend recalled. “We sort of thought that you couldn’t win, as a woman.”

One woman did get some measure of vindication right around this time. In February 1992, Mike Tyson was found guilty of one count of rape and two of criminal deviate conduct against Desiree Washington, an 18-year-old beauty pageant hopeful. Upon Tyson’s conviction, however, prominent figures quickly spoke out in his defense. Donald Trump said, in a series of interviews, that the boxer had been “railroaded,” that the trial was a “travesty,” and that Tyson’s teenage victim had “wanted it real bad.” Alan Dershowitz, who would represent Tyson on appeal, wrote a cover story for Penthouse: “The Rape of Mike Tyson.” Dershowitz said that Washington may have felt that she’d been raped, but Tyson “reasonably understood” that he’d gotten her consent.

Washington, for her part, alleged in an interview that someone had offered her more than $1 million to recant her claims before the trial started. She said this person, whom she didn’t identify, had suggested that Washington say that she was “afraid because of what happened to Patricia Bowman, that I was afraid because of how Anita Hill was exploited.” The lead prosecutor in the trial expressed his admiration for Washington after the verdict was announced. “She’s a young person with a lot of courage,” he said.

According to another one of Cindy Powell’s friends, it was exactly this—Desiree Washington’s courage—that inspired Powell to go back down to Port St. Lucie. On March 3, 1992, just a few days into Mets spring training, she turned the semen-stained dress over to police and gave investigators a statement laying out what Dwight Gooden, Daryl Boston, and Vince Coleman had allegedly done. A week later, she picked the three Mets out of a photo lineup and provided a 29-page, handwritten account of the incident that included labeled sketches of Gooden’s home.

“I feel like I have to face my fear right now, come forward and let them know they can’t get away with this,” she told police. “I’m bitter and I’m a victim.”

9.

On March 12, reporters overheard David Cone in conversation with a Mets coach. “We have a serious problem,” Cone said, before gathering his teammates for a closed-door meeting.

The headline in the next day’s Palm Beach Post spelled it out: “Woman says three Mets raped her.” Gooden was the first of the accused to be identified; the others’ names would come out a short while later. Cone would be the only Met to give a statement: “Obviously, this is a big test for our team. But frankly, this issue supersedes baseball. I’m more worried about these guys’ lives.” He would later tell police that the Mets who’d been accused had come to him for guidance: “I guess they considered me some sort of expert, after what I’ve been through in Philly.”

For the next four weeks, the rape investigation would be covered relentlessly by the press. Reporters followed Powell to her therapist’s office and prowled a Manhattan bar called Perfect Tommy’s, where she’d worked as a waitress. “It was an insane frenzy of phone call after phone call,” recalls Steve Wastell, a bartender at the time. Eventually, producers at Inside Edition realized they had some footage of Powell in their files. Perfect Tommy’s had hosted a game in which patrons put on Velcro suits, bounced off a trampoline, and tried to stick themselves, upside-down, to the wall. In the tape, the Palm Beach Post reported, Powell could be seen wearing “a midriff-bearing top and shorts.” Wastell says that Inside Edition, which obscured Powell’s face with a dot, tried to make her out to be a bimbo on the basis of her outfit. “They really spun that one,” he told me.

In The Worst Team Money Could Buy, John Harper wrote that “[b]attle lines were drawn” between the Mets’ beat guys and the newly arriving packs of general-assignment reporters. Harper recalled that he and the other clubhouse writers tried to stay chummy with the players as their colleagues sifted through the scandal. The beat writers found the New York Post’s Andrea Peyser particularly annoying. Peyser publicly called out the hypocrisy of sports writers who “coddle and suck up to athletes” as she herself sought to pull the cover off the Port St. Lucie groupie scene. One of her Post colleagues, columnist Steve Serby, lambasted such coverage as “Sex Lives of the Rich and Famous, or Sex and the Single Met.”

Peyser’s write-ups of “Swing Training,” as well as her reporting on the lawsuit alleging that Cone had exposed himself in the Shea Stadium bullpen, caused several flare-ups in the locker room. “You’re a liar! A fucking liar!” Cone screamed at her at one point. He went on to lead a team boycott of the media, on account of what the Mets players described as “slanderous and stereotypical attacks.”

In the meantime, a Port St. Lucie police lieutenant had traveled up to New York City to conduct interviews with witnesses, including Powell’s friends and relatives and people she’d interacted with as a bartender and waitress. On March 30, 1992, investigators used a warrant to procure blood and saliva samples from Gooden; police DNA tests found a match, at “98 percent probability,” to the stain on Powell’s dress. Gooden’s lawyer said this didn’t prove his client had sex with Powell, saying the test “only narrows it down to exclude 98 percent of the people.” Gooden would later admit in one of his memoirs that he and Powell did have sex, but he’d say it was consensual.

Media coverage of these developments mixed reportage with sleaze. On his morning radio show, Howard Stern pretended to masturbate when he heard the news about the semen stain matching Gooden’s DNA.

Powell went back to Port St. Lucie and on March 31 spent another five hours answering questions related to what law enforcement officials said were “minor inconsistencies” in her account. The police tested her story by analyzing the level of stress in her voice: When Powell was asked whether she’d been forced into Gooden’s bedroom, or forced to have sex, an officer concluded that she “did not respond truthfully.” This form of testing would not have been admissible in court. A subsequent field test of voice-stress analysis found a false-positive rate of 8.5 percent—that is, about 1 in 12 people that the test deemed liars were in fact telling the truth.

The three Mets never gave statements to law enforcement. Their attorneys did arrange to have their clients take commercial polygraph tests. The tester they employed found “definite indications of truthfulness” when they denied having assaulted Powell. This test, too, would not have been admissible in a legal proceeding.

Gooden, Coleman, and Boston also hired a state-trooper-turned-P.I. named Jack Brucato. “The Port St. Lucie Police Department … were cordial enough to give me a couple of weeks to look into it,” Brucato told me.

There were so many reporters around, Brucato said, that he’d had to wear disguises: a fake beard and mustache, a wig with dreadlocks. Brucato told me that he found good evidence that Powell had lied about her interactions with the Mets on the night of the alleged rape. He claims that witnesses at Banana Max described seeing her “muscle her way amongst the players” and “more or less take over the conversation.” She was being “very aggressive,” he says. “Anybody with common sense would realize this girl was possibly trying to set them up for money.”

Scott Bartal, the Port St. Lucie police officer who supervised the investigation, also didn’t believe that Powell was telling the truth. “There were things that just didn’t line up,” he told me. The fact that she’d made the bed and kissed the players goodnight didn’t fit with his idea of how someone would respond to having suffered through a traumatizing event.

Bartal says that when news of Powell’s allegations became public, he fielded a call from William Kennedy Smith’s accuser. Patricia Bowman wanted to get in touch with Powell, he remembers, so she could offer her support. Bartal says he passed the message on. He also told me he thought it was suspicious that both women claimed to have been raped on the same night.

In Bartal’s view, the most damning detail of all concerned the conversation that Powell reported having had with Boston a few days after the alleged rape—their “mum’s the word” exchange. “That sealed it,” he told me—he didn’t believe that someone who’d been assaulted would say anything like that to her attacker. When Powell mentioned that phrase during her final five-hour interview with the police, Bartal perked up. “The victim knew that I knew that it wasn’t really as she had reported it,” he told me. Bartal also said he believed Powell had picked up Gooden at Banana Max—that she’d made “goo-goo eyes” at him—to punish David Cone for not spending time with her that night. “She figured that if she’d go with Dwight Gooden, David Cone would get jealous.”

The transcript of that final police interview ends with Bartal telling Powell: “To be perfectly frank with you [Cindy], I’ve got a lot of problems with your story.” He turns off the tape recorder shortly thereafter at Powell’s request, and the transcript ends. The case file indicates that the next time Powell spoke with the Port St. Lucie police, on April 2, she was very upset, and she accused the department of having been paid off by the Mets. (There is no evidence that the Mets organization or anyone else paid off the police.)

On April 9, Florida State Attorney Bruce Colton announced that no charges would be filed against the players. He cited several issues that contributed to what he termed the case’s “vulnerability”: that it had taken several days for Powell to realize that she’d been raped; that she’d never gone to a hospital to be examined; and that she’d waited a year to file a report. The lie-detector tests and the voice-stress analysis were not major factors, he said, but did play into his reasoning. “We have to make our decision—not based on whether we believe the victim—but whether there was a likelihood of conviction,” Colton said.

“There’s tremendous relief, but no elation, no joy,” Cone told the New York Post.

Although Cindy Powell was never publicly identified, Gooden’s lawyer told reporters that she should lose the protection of anonymity. “I’m sensitive to the rights of women and the rape-shield law,” the attorney said in April 1992, “but I think it’s highly, highly unfair, now that a decision has been made, that she can hide behind the rape-shield law after the damage that’s been done to these players’ reputations.” He suggested that Gooden might file a civil suit against his accuser. That never happened.

In the meantime, details of Powell’s brief sexual relationship with Cone—and of her friend Brenda’s reported liaisons with Cone and Darling—were folded into news reports about the investigation’s end. On April 10, the New York Daily News ran the cover line, “NO CRIME BUT RATED XXX.” A two-page spread inside had the headline, “Sex and Baseball: It’s Amazin’,” while the story below described the rape investigation as having offered “a voyeuristic view of a hidden world of professional baseball and raw sex.” The next day, Brenda was quoted in the New York Post, with her guess of what happened at Gooden’s house. “Obviously, later on, she felt used and coerced. In her mind, she does believe she was raped,” she told Andrea Peyser. Then she added: “There’s such a fine line where consensual sex ends and rape begins.”

10.

The Mets lost 90 games in 1992 and finished in fifth place.

Daryl Boston was released when the season ended. He’d play two more years in the major leagues, then work as a coach in the Chicago White Sox farm system. He’s back in the majors now, having just completed his seventh year as Chicago’s first base coach.

In 1993, Vince Coleman accidentally struck Dwight Gooden while swinging a new golf club, injuring the pitcher’s shoulder. A few months later, Coleman allegedly tossed some kind of explosive—reports suggested it was either an M-80 or a cherry bomb—near a crowd outside Los Angeles’ Dodger Stadium. Among those injured was a 2-year-old girl. Coleman said it was an accident, and that he’d “dropped” the firecracker rather than thrown it. Nonetheless, he pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor count of unlawful possession of an explosive device and was sentenced to 200 hours of community service. Mets co-owner Fred Wilpon said that was it—the team was done with Coleman. He’d play four more seasons in the majors after the Mets parted ways with him. In recent years, Coleman has worked as a baserunning coach for the White Sox and San Francisco Giants. He told Slate that Powell’s allegations were completely false. “Nothing happened,” he said in a brief phone call. “You should write about something good instead. Write about God, and the good that God does in the world.”

When the 1993 season was over, the Mets had a record of 59–103, completing their descent from the best to the worst team in all of baseball.

Gooden, for his part, became a kind of baseball dinosaur—a fallen hero from a prior age. As a Met in 1994, he failed a drug test for cocaine and received a two-month suspension, then kept using when he was supposed to be in treatment. At a hotel in Tampa, Florida, he binged on coke all through the night in the lead-up to a scheduled drug test. When he later learned that he’d be suspended for a year, he put a gun to his head and waited for his two daughters and his wife—then eight-and-a-half months pregnant—to find him. The gun had no bullets in it, he confessed in his most recent memoir. It was “suicide theater, not a suicide attempt” and “a shitty, shitty thing to do.”

The Gooden billboard in Manhattan was taken down in 1995.

The other idols of those prelapsarian Mets, the rowdies who won it all in ’86, remain staples of New York media, their successes lionized and their sins reconstrued as locker-room foibles. Hernandez and Darling now call Mets games for SportsNet New York; Cone announces games for the Yankees’ YES Network. These three former Mets have published eight memoirs between them; each put out a new one within the last two years. Gooden and Strawberry remain central to New York sports fans’ imaginations as largely sympathetic figures. They both went on to play for the Yankees, along with Cone. In 1996, they helped that team—often lauded for its humility and virtue—win the first of four championships in five years.

Gooden, by his own admission, has never shaken his addictions. This past summer, he was arrested twice in New Jersey, first for cocaine possession and then for driving while intoxicated. (He pleaded guilty to the cocaine charge and will avoid prison time if he completes another stint in drug rehab. The DWI case is still pending.) “I have no excuse for my action,” he told a Newsday reporter in July 2019, after his DWI arrest, adding, “This is the worst I’ve ever been through all my struggles.”

In response to a detailed request for comment, Gooden’s lawyer sent Slate a statement: “Dwight would never, and had never forced himself upon anyone, nor has he ever coerced anyone into anything. These are false allegations which were investigated at the time and a proper determination was made that no one should be arrested. It’s most unfortunate that almost 30 years later this is being discussed.”

11.

There was some talk, in April 1992, that Cindy Powell might file a civil suit. When the state of Florida announced it wasn’t pressing charges against Gooden, Coleman, and Boston, Powell’s lawyer told reporters that he’d explore what “other relief” might be available to her. But Powell never sued the Mets players. She wanted to move on.

Although the story of Powell’s allegations disappeared from newspapers in the spring of 1992, another account emerged that September, in a Penthouse story that promised “an exclusive account of three Mets’ side of the story.”

The narrative, laid out by Palm Beach–based journalist Linda Marx, differed wildly from Powell’s description. Marx wrote that Powell had hit on Gooden at Banana Max, and that she and all three players agreed to go back to Gooden’s house together. When they got there, the Penthouse story said, Powell had consensual sex with Gooden right away while Boston and Coleman stayed in the living room playing Nintendo. After a while, according to Marx, Powell emerged from the bedroom and said, “Dwight has a big dick!” From there, “groping, kissing, and fondling ensued in the living room,” followed by consensual group sex. “I’ll do two at a time—not three,” Powell supposedly told the Mets.

According to the Penthouse story, Powell asked at the end of the night if she could sleep over. The Mets said no.

While Marx attributed certain details to Gooden, the story’s sourcing isn’t clear, and Marx told me she can’t recall whether she spoke to the players directly. Gooden’s 2013 memoir does provide a pared-down version of this account. He writes that all three Mets had consensual sex with Powell that night. Gooden also claims, without citing any evidence, that Powell “had some history making similar allegations,” and that this contributed to the fact that her “case began to fall apart.”

Powell did not challenge the Penthouse piece in public. How could she? The players never talked to police, and the article came out only after the case was closed, when Powell’s allegations had already been dismissed. But the story caused her enormous pain, according to a longtime friend who asked not to be named.

Another close friend, who also requested anonymity, said that Powell became more inclined to use drugs and alcohol in the years that followed her alleged assault. Several friends suggested that she went on to suffer bouts of mental illness. Powell might stay awake for days, one told me, making jewelry for a special order, or would spend hours cleaning up her kitchen. She showed signs of paranoia, too, and worried that people close to her were out to take her money.

While Powell and her mother remained close, her brother died suddenly in the mid-2000s. Her biological father had also died not long after she went to the police. “There was just so much loss in her family,” the friend told me. “I remember she always used to say, ‘Who’s going to take care of me?’ ”

Back in 1992, the New York Post had led the city’s coverage of the rape investigation in Port St. Lucie, and of the groupie scene around the Mets. Andrea Peyser, in particular, had boosted her career thanks to her reporting on the scandal, becoming a well-known columnist.

Peyser, who now focuses on politics and culture wars rather than sports, returned to the story that made her famous in February 2012. In a piece the Post headlined “Getting jilted & crying rape doesn’t fly,” she focused on a fresher scandal: a 29-year-old paralegal’s allegation that she’d been raped (and impregnated) in her law office, while blackout drunk, by a local anchorman who happened to be the son of New York City’s police commissioner. The Post, and Peyser, were skeptical. When the DA’s office dropped the woman’s case—“the facts established during our investigation do not fit the definitions of sexual assault crimes under New York criminal law,” they explained—the Post ran a full-page photo of her above the headline: “SHADY LADY.”

This all reminded Peyser of the case she’d covered 20 years before. “Times have changed, and so have the players,” Peyser wrote. “But one thing remains constant in affairs of the heart and other body parts—give it up too easily, and he won’t love you in the morning.”

She went on to tell the story of what happened at spring training. “Afterward, the lady made the bed,” Peyser wrote in 2012. “A year went by. Cone was gone. She never heard from the gang-banging trio again. Then it hit her. ‘I’ve been raped!’ ” The column continued: “She should have hit the gym or drowned her sorrows in whiskey. Because after a monthlong investigation humiliating to all, prosecutors determined that while the players got freaky, the sex was consensual.”

In 1992, Peyser had reported a different—and far more accurate—set of facts. Less than a week—not a year—had passed before Powell told her friends that she’d been raped, and placed her first tentative call to the Port St. Lucie police. And back then, Peyser had been clear about the prosecutor’s determination in the case, which did not include any kind of official pronouncement about whether Powell and the players had sex, much less whether the sex had been consensual. “State Attorney Bruce Colton appeared to be sympathetic to the accuser,” she wrote at the time, “but said her charges would be too difficult to prove in court.”

To finish out the 2012 story, Peyser called up Powell, who at that point was in her early 50s. She asked Powell how she felt about her accusation in retrospect. “I’ve made peace with it,” Powell told her. “I did what I had to do.”

Peyser responded, in her column: “But at what cost—to women?” (Peyser didn’t reply to messages seeking comment.)

Around this time, Cindy Powell was still a jewelry-maker. She also created sculptures that she’d photograph and post to Facebook. She built plastic fish, handbags, and dollhouse chairs from odds and ends that looked like they’d been scavenged from the beach. She designed a set of mounted, deconstructed dolls, some with their eyes or mouths distorted. She constructed a glittery armchair out of embellished fabric and disembodied Barbie limbs.

In the summer of 2012, she died by suicide.

“There was no memorial or anything for her,” one of her friends told me. “You know, it was almost as if she didn’t exist.”