The first songs most people hear as children are nursery rhymes and lullabies. The first songs Ahmet Zappa heard as a child were the shock-treatment tracks on Hot Rats, a groundbreaking 1969 set by his father Frank. “This is the stuff I was drinking my milk bottles to,” Zappa said with a giggle. “It’s magical.”

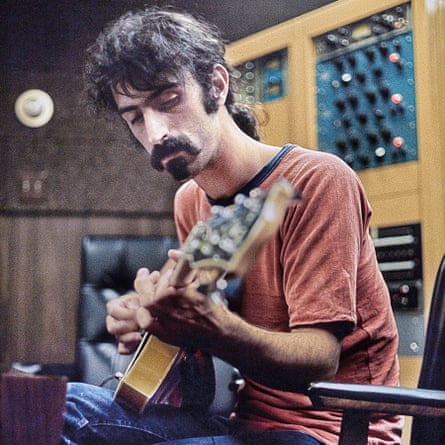

He isn’t the only one who thinks so. Though Frank Zappa released no fewer than 62 albums in his too-short life – and though nearly as many sets have appeared since his death from prostate cancer at age 53 in 1993 – none sound quite like Hot Rats. It’s a work of such imagination, humor and freedom, it could appeal to a child as easily as it could a stoner, a rocker, or a fan of the avant garde. Zappa’s first true solo album, Hot Rats introduced new recording techniques, melded previously segregated styles, and even presaged a new musical genre. It also broke with the structure of previous Zappa releases. It resonated with progressive rock fans in a way no other Zappa album has, earning generous FM radio play while sending it into the UK top 10, boosted by one of the most recognizable instrumental tracks of the psychedelic era, Peaches En Regalia.

To celebrate, and document, all these innovations, the Zappa Trust are releasing a six CD box set compiled of Rats-related material, timed with the album’s 50th anniversary. There’s also a related tome titled The Hot Rats Book, which concentrates on photos taken from the album’s historic sessions by Bill Gubbins. And Dweezil Zappa is currently on the road with a tour titled Hot Rats & Other Hot Stuff, which features material from the album. “With this box set, for the first time in 50 years you get to hear the whole composition of each song as it was recorded, and as it developed,” said Joe Travers, who has served as “vaultmeister” of Zappa’s music for the last 27 years and who helped curate the set.

While many box projects that intend to chronicle, and illuminate, classic albums waste space with mild variations on the official versions of a song, most of the tracks on the Rats box differ greatly from those listeners have previously heard. The dense and raucous jams that inspired the final cuts have been fully restored, and assembled in an order that makes the development of the official versions clear. “It provides context for the final product,” said Ian Underwood, who played a plethora of instruments on Rats and who is the only musician, besides Zappa, who appeared on every track. “Like ‘process art’, you can hear all the things leading up to a track, so you get a feel for how it arrived at the end. It’s also interesting to see what didn’t work out along the way.”

The explorative quality that informed the project reflected an especially fraught, and productive, period in Zappa’s career. He had just broken up the original Mothers of Invention, due to the cost of maintaining them and the toil in rallying them. And four months before he entered the studio for the Rats sessions, he wrapped production on another milestone album, Trout Mask Replica by Captain Beefheart. Technically, Hot Rats was Zappa’s second solo album, though his first, Lumpy Gravy, was an orchestral work which he conducted rather than played on. “Frank always considered Hot Rats his real solo debut,” Travers said.

The music itself was nearly all instrumental. For Rats, Zappa ditched the satirical lyrical pieces that helped define the Mothers. There’s only one vocal segment, from Captain Beefheart at the start of Willie the Pimp, a low-down blues rock track which he delivered like a surreal Howlin’ Wolf. The lyrics in the song contain the album’s title which, Frank reveals in a spoken word section of the box set, was inspired by an Archie Shepp recording of The Shadow of Your Smile. “He played this solo that sounded to me like an army of pre-heated rats screaming out of his saxophone,” Zappa says on the set.

To suit the wildness, most songs on Rats last far longer than those on the Mothers albums to that date, elaborated by roiling jams, especially in the nearly 13-minute The Gumbo Variations. The only Mother member retained for the final album was Underwood, though several others from the band, including Roy Estrada and Jimmy Carl Black, performed on sessions which are revealed for the first time on the box set. Underwood considered the elaborately composed music Zappa gave him to play for the album challenging. “You can’t play those parts by just looking at them and fobbing them off,” he said. “You have to really pay attention.”

For the rhythm section on Rats, Zappa hired experienced session guys, including drummer John Guerin and bassist Max Bennett who, collectively, worked with everyone from Ella Fitzgerald to the Partridge Family. But the standout hires were Don “Sugarcane” Harris and Jean-Luc Ponty, who each played dynamic electric violin. It’s one of the first, and certainly the most influential, uses of that instrument in a popular setting, presaging a whole trend in rock bands employing electric violins, from Papa John Creach in Hot Tuna, to David Cross in King Crimson to Jerry Goodman in Mahavishnu Orchestra. In fact, Mahavishnu leader John McLaughlin first wanted to hire Ponty as his violinist, based, in part, on Hot Rats, but immigration problems forced him to look elsewhere. The jazz-rock fusion style that Mahavishnu advanced in 1971 can be traced directly to Rats. In fact, Rats rates as one of the first-ever fusion albums, along with works recorded in the same year by Miles Davis and the Tony Williams Lifetime. More, Rats was the first Zappa album that made full use of 16-track equipment, allowing the star to easily overdub every crazy sound in his head. “He could greatly expand his sound palette,” Travers said.

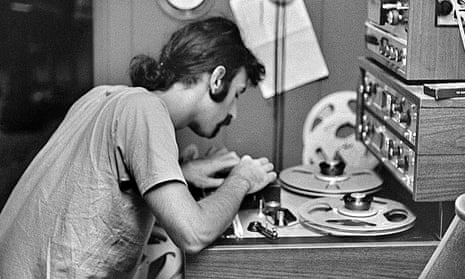

The album also saw Zappa greatly advancing techniques he had earlier attempted in tape speed manipulation. “Frank would take one instrument, like the bass guitar, and do tape adjustments that, once sped up, would sound like a clarinet,” said Travers. “Or he would speed it up even further to stand in for a flute.”

The result gave some of the music a highly animated, and decidedly comedic, sound, especially in Peaches En Regalia. In sections of that song, Underwood’s array of woodwinds and horns had the character and color of cartoons, to the listeners’ delight. “Frank said Peaches is a song that nobody disliked,” Travers said.

Similarly, the whole album had an infectious energy, giving it a connection to the great psychedelic rock albums of the day, despite all its avant-garde, jazz and classical influences. Though Ahmet Zappa pointed out that “Frank was never motivated by commercial success,” he did write humorous radio commercials to lure people into the music. One, included on the box set, features an authoritative voice announcing, “the music was written by Frank Zappa. In spite of that fact, we think you should obtain it.”

“Frank was aware of the image he had,” Travers said. “He knew that Hot Rats was a departure and he wanted people to give the album a chance.”

Those that did so found a work cohesive enough to live up to Zappa’s description of Rats as “a movie for the mind”. “If you listen to the whole album, it’s a progression,” Underwood said. “It’s not just a series of cuts and then you’re done. There’s forward motion.”

Given that, it’s no surprise that Ahmet Zappa – who wasn’t born until five years after the album appeared – has found Hot Rats entrancing since childhood. “My father was a musical warlock,” he said. “The music he wrote then was just unreal.”