When news broke that Daniel Johnston, cult musician and visual artist, died of a heart attack on September 11, 2019, at his home in Waller, Texas, tributes from fans and fellow musicians flooded in. The lo-fi, homespun humanity of his songwriting, immortalized in Jeff Feuerzeig’s 2005 documentary The Devil and Daniel Johnston, had touched mainstream figures like Beck, Wilco, Bright Eyes, Sonic Youth, and Pearl Jam — many of whom covered Johnston over the years and came to know him as an icon of outsider art. As Feuerzeig’s film aptly captures, the life of the Hi, How Are You songwriter was dotted with triumph and tragedy; diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, he was institutionalized numerous times throughout the course of his career. Nevertheless, Johnston, who was 58 at the time of his passing, continued to create art until his final days.

In the weeks following his death, Feuerzeig worked with Vulture to track down and speak with some of the late musician’s closest friends and collaborators. Together, they wished to host a digital wake for their dearly departed friend, simultaneously and lovingly described as a genius and a con artist, a brilliant creative and a pain in the ass. Some chose to write their own remembrances of the cultural phenomenon, while others relayed their memories by phone. Here they are, lightly edited, in honor of Daniel Johnston:

He Was Abraham Lincoln and Jesus Christ

Louis Black (co-founder of SXSW/Austin Chronicle): I first met Daniel when I was at the Chronicle on a Saturday alone, when the paper was still struggling. I heard a shuffling outside the door, a knock, and I opened it to see Daniel, whom I didn’t know at the time. He said, “Hi, my name’s Daniel Johnston and here’s my tape,” which was what he said to everybody at the time. I was preoccupied with writing, so I said, “Okay, I’ll give this to some of the music writers, but I can’t promise anything.” I closed the door and went back to work, but the shuffling continued.

I opened the door back up, and Daniel said excitedly, “I didn’t give you that tape to be reviewed! I gave that for you to listen to it!” I never listened to stuff immediately then, but I put it on, thinking I’d only listen to half a song, but I listened to the whole thing. I started playing it for anybody who would listen. I wasn’t sure exactly what it was, but it was really impressive. Daniel was like ten people at any given time in his head. All those voices were in the room, and talking at once. One minute he was totally innocent, and the next, a con artist. He’d have no idea what was going on, or more of an idea of what was going on than anybody. He’d manipulate, then be in awe of you, all at the same time. It was hard to read him, and I don’t think he was ever entirely in control. Our relationship progressed because I was a fan, and I was at a lot of the early shows. He liked to drive me crazy, and I’d be banging the phone on my desk. I wrote the first piece about him in the Chronicle, and he said, “Yeah, but why didn’t you give me the cover?” He would push, and he was brilliant about knowing what buttons to push. I would get calls from Abraham Lincoln and Jesus Christ, but I always knew who it really was.

Daniel was definitely a hustler, and loved pissing people off. I remember reading that he went on an anti-Semitic tirade at some club in the Midwest, which was funny because I know he was doing it to get a rise out of people. When The Devil and Daniel Johnston came out, Daniel was heavily sedated, so when you were with him, you didn’t really get to see Daniel. We were showing the film at the Alamo Drafthouse, where I was going to talk after, and Daniel would play a few songs. We were all upstairs in the office, when suddenly Daniel remembered how he used to drive me crazy. He was old Daniel again, and I hadn’t seen that for a while. Mischievous, sweet, and a pain in the ass. Toward the end, he was old Daniel again, too, and it was great.

His First Show in NYC

Ken Katkin (Homestead Records): I first heard Daniel when I was in college at Princeton sometime in the mid-’80s. By chance, one of my housemates was from Austin, and when he was back home, he heard about this local guy who worked at McDonald’s, who would give out cassettes. My housemate got a couple cassettes directly from Daniel. I was hearing those sometime around 1986, and Daniel wouldn’t charge anything for the cassettes either. You just went into McDonald’s and he’d give them to you. Eventually, Jeff Tartakov started making those cassettes for him, and would charge two or three bucks for them. Before Jeff, Daniel made the tapes himself and would sometimes put them in the takeout bags without people knowing it. They’d order a Big Mac and find a Daniel tape in there with their fries.

My housemate and I worked at the Princeton radio station, and we started playing Daniel’s cassettes on the air. About a year later, Daniel still only had these cassettes out, with nothing on any other format. The Village Voice was the weekly paper in New York City, and everybody read it. The Voice writers were going on strike, so they organized a strike-fund benefit concert, with co-headliners Sonic Youth and Public Enemy. The Voice writers gave those two groups the ability to put other artists on the bill, and Sonic Youth added Half Japanese, along with Daniel Johnston.

At that event, which was at the Cat Club in NYC, very, very few people would have known Daniel Johnston, and I probably wouldn’t have known, if it wasn’t for my housemate. It ended up being around 12 bands on the bill, so all the non-headliners were told to keep it short. It was a decent size club of about 1,000, and Daniel was told to keep it to three songs. He got onstage with his acoustic guitar, and along with his voice, it was not what the crowd was expecting. He played “Don’t Play Cards With Satan,” and after his three songs, he just kept going.

The guy in the DJ booth was frantically trying to signal him, like, “Hey, man, you’re done!” Daniel kept right on going, so then the DJ turned down Daniel’s volume. That didn’t stop him, so then the guy just put on a record to drown him out. Daniel stopped, but didn’t appear to be in any hurry to leave the stage. He started pacing the stage and yelling at the DJ, calling him Satan and accusing him of doing the work of the Devil by shutting off his music. Finally, Daniel jumped off the stage and marched straight for the DJ booth, and tried to yank the record off the turntable, and we could all hear the needle scratching. He finally stormed out of there, and I believe that was his first NYC show.

A ‘Speeding Motorcycle’ Story

Ira Kaplan (Yo La Tengo): We had learned “Speeding Motorcycle” and recorded our album Fakebook, but I don’t believe it was out yet. We came in to do Nick Hill’s show on WFMU, who had heard us doing that song and had gotten Daniel to call in to the show. We did a set of our songs, and then Daniel called in and sang. There was no sound check, or thought to how it would really work, so we just leaped into it. As the recording makes clear, nobody knew what was going to happen, and communication was tricky at best. We did three songs, two of them that, with any luck, you’ve never heard because the technical issues of Daniel singing into a telephone, along with a band that he can’t hear, was pretty rough. But “Speeding Motorcycle” was just a magical moment. It wasn’t our moment; we were just lucky to be there, hearing this guy pour his heart into a telephone receiver. It was just incredible.

A Song About Mountain Dew

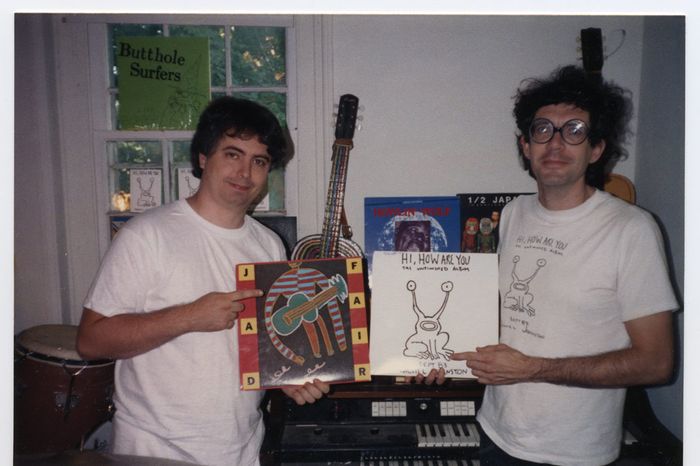

Jad Fair (Half Japanese): I first heard Daniel in 1985. Half Japanese had a show in Austin and Daniel’s manager, Jeff Tartakov, gave me a tape of Hi, How Are You? I loved it and began corresponding with Jeff and Daniel. A few years later I was in NYC to take part in a recording session of Moe Tucker at Kramer’s studio Noise New York. Daniel was at the studio and he and I became friends. Daniel recorded two songs with lyrics I wrote. He recorded “Do It Right” for Moe’s album, and “Some Things Last a Long Time” for his album 1990.

While Dan was in the hospital, I would often get phone calls from him at 2 or 3 a.m. He would call to let me know he was working on a song about his favorite soft drink, Mountain Dew. At the end of each call I would tell him that it was good to talk with him, and suggest that he call during the day instead of so late at night, and the next day it would again be in the middle of the night. I just remembered another phone call I had from Daniel. Dan called me and told me that he was going to have all of his teeth removed. I told him that I was sorry to hear that he would have to have it done. He then told me he was looking forward to it, that it would be good for making funny faces.

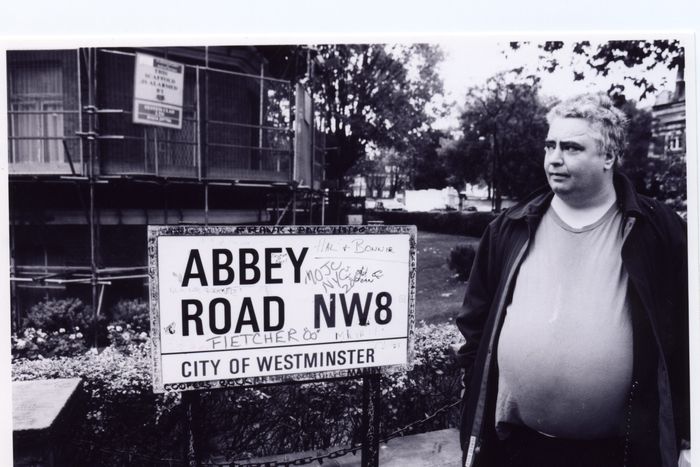

The Wire magazine arranged for a photo shoot in London. A photo of Daniel and me was to be used on the front cover. The photographer took three photos and Daniel said, “Thank you,” got up, and left the room. I went after him and reminded Daniel that it was for the cover. I asked him to have more photos taken. He went back and after two photos he said he was going to get a hamburger. He left the room, and I couldn’t talk him into going back.

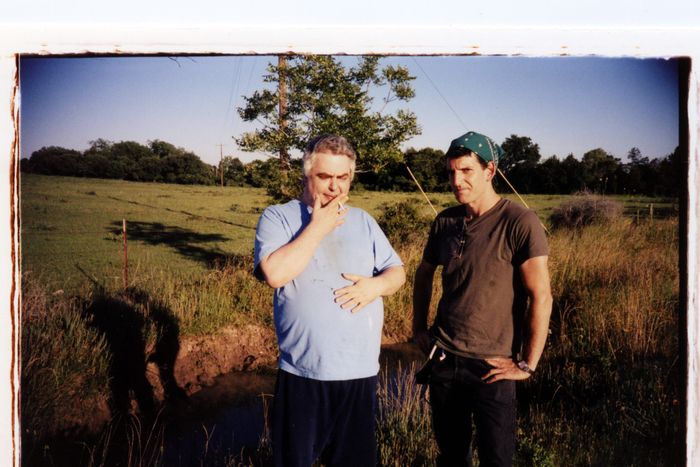

King Kong Johnston

Henry S. Rosenthal (producer, The Devil and Daniel Johnston): In the year 2000, when Jeff Feuerzeig and I decided the time was right to make a film about Daniel Johnston, we had a very modest project in mind. It wasn’t until we arrived in Waller, Texas, and embedded ourselves in the Johnston family home that we quickly realized the immensity of the family and Daniel’s archive there, and how it could evolve into the epic that, four and a half years later, emerged as The Devil and Daniel Johnston.

Attempting to work directly with Daniel was difficult. Climb Mount Everest difficult. Land on Mars difficult. He was often obstreperous and hostile to the filmmaking process altogether. Arriving prepared with a detailed timeline of Daniel’s life to use as a road map to guide us, we began to build the thematic scenes that would eventually link together to be the film. Part of that process was abandoning preconceived notions, being open and very present with the chaotic day-to-day events unfolding in the home.

In the midst of filming, Bill Johnston, Daniel’s now deceased father and then-manager, received a fax from Austrian performance artist Peter Friedl inviting Daniel to fly to South Africa, all expenses paid plus $1,000, to appear in a video called “King Kong,” to be based around Daniel’s song of the same name, combining it with a controversial moment in South African cultural history, the 1959 jazz opera King Kong, based on the tragic life of boxing champ Ezekiel “King Kong” Dhlamini. The plan was for Daniel to wear a gorilla suit during the performance video, and he was excited for that reason alone. Despite Daniel’s delicate condition and his difficulty traveling long distances, Bill jumped at the opportunity for Daniel to prove himself a profitable servant and booked it.

As we saw these events unfolding in real time, Jeff and I were faced with the decision whether to document the creation by following Daniel to South Africa, a costly and resource-intensive commitment, or attempt to produce documentation remotely by hiring a local crew as a second unit. After locating a cinematographer with the proper Super 16mm camera, lenses, and experience, we remotely guided him through the process of obtaining what we needed in order to create the scene. This included filming Daniel’s arrival in Cape Town, mirroring, in our minds, the arrival of the Beatles at New York’s Kennedy airport on February 7, 1964; fly-on-wall footage of the creation of the video; and highlights of Daniel’s trip. This came to include Daniel’s lethargic and disoriented appearance on The Toasty Show, a local morning network entertainment program. We stayed in close contact with our remote crew through Daniel’s visit and heard the blow-by-blow account of the difficulties on the set of Friedl’s production, and it certainly came as no surprise to us to learn that all Daniel wanted to do was visit comic shops and record stores, just as he did in Waller, Austin, and everywhere else he went in the whole friggin’ world.

After reviewing our footage of the South African adventure, we encountered resistance from the artist Peter Friedl, withholding access to clips from his production to be used to complete the scene for our film. After getting a chance to view Friedl’s completed “King Kong,” we saw a zonked-out Daniel slumping on a park bench in a public park, wearing only a gorilla mask, not a suit(!), just his normal street clothes. After all that travel and effort, the result was far from interesting, and we had no compelling scene. We had taken an artistic risk and failed.

Clenched in the jaws of defeat, we looked out at the sprawling field behind the Johnston family home and realized that if we shot away from the house, and used black-and-white film, we could simulate the African veldt and make our own King Kong, and do it much better than the questionable Teutonic production we had seen. I sprang into action, calling my wife in San Francisco to ask her to FedEx one of my two gorilla suits to us in Waller. Now, I believe that every gentleman should own his own tuxedo and his own gorilla suit. Striving for exceptionalism, I own two of each.

The suit arrived in its large black duffel bag, and Daniel was genuinely excited to wear it and act out the story of his song, a laconic and fatalistic retelling of the King Kong story. Jeff enthusiastically approved the wardrobe, and we were thrilled to use Daniel’s own Fay Wray Barbie doll as his love interest in the film within a film that we were producing.

On the day of our shoot, we set up a tall stepladder in the Johnston’s back forty while Daniel squeezed into his simian sartorial splendor. As Daniel ascended to the top of our Empire State Building, erstwhile the aforementioned stepladder, his father Bill donned a WWI pilot’s cap, and while holding one of his many propeller-fighter-plane models, circled the Eighth Wonder of the World, peppering him with an imaginary barrage from Browning M1918 .30 cal aircraft machine guns, the very same used to subdue the beast in the 1933 original film. Daniel Kong swatted helplessly at the circling death machine, and realizing his impending mortality, tenderly placed the Fay Wray doll safely on a ledge before his historic fall to Fifth Avenue 102 stories below. Pilot Bill circled the death scene gleefully and flew the plane right down the barrel of our lens, completing the scene. King Kong Johnston is dead, but this incredible footage, which never made it into the final cut of The Devil and Daniel Johnston, can still be seen among the DVD bonus material, because in the words of Carl Denham, the cynical filmmaker who first captured Kong on Skull Island, “Oh, no, it wasn’t the airplanes. It was beauty killed the beast.”

A Trickster and a Coyote

David Thornberry (Johnston’s longtime best friend): Imagine Harpo Marx, but instead of never talking, he never shuts up. Imagine Charlie Chaplin, the innocent, naïve wisdom. My friend Dan Johnston was a trickster, coyote, and like all tricksters, he sometimes tricked himself. I would love to watch a secret movie of the two of us in our 20s walking our 2 a.m. streetlight wanderings around East Liverpool, Ohio, poking through dumpsters behind record stores and singing songs about all-night-grocery-store checkout girls. (Hello, Shirley whatever-your-last-name-was.) Oh, Dan, you should have been excused, exempted from having to grow old and die. You should have been allowed to just stay 22 and live forever, drawing and singing and whispering into your tape recorder. Sometimes, you colored so far outside the lines that even I couldn’t go with you, sometimes you just wore me out with your creative craziness, your social experiments using everyone else as lab rats.

But I loved you. I loved you. You showed me that art is important and necessary, in contrast to what our small Appalachian Mountain town culture showed us every day. You showed me that we weren’t freaks and misfits; we were ARTISTS, and that Artlife is a blessing, not a curse. Thank you for that. You were half-angel and half-devil, and no one, not even you, knew which half was who or what or when. Everything was “great”; “That’s great! That’s really great!” I’d hear so often about everyone else’s art efforts. You were so generous with your support and praise. Making all kinds of art was fun and you wanted everyone to have fun. Mischievous, irritating, hilarious, exhausting, deeply talented. A genius, really, a real genius to the point of having almost no social skills or workable ideas about getting along in society. You just wanted to create. You were an animal, pure and intuitive and singularly focused. You knew that you would be famous, that you’d someday be John Lennon. You are famous. I like your songs better than John’s. Imagine that.

And finally, without you in my life, Dan, I’d never have met or married Kathy McCarty. Thank you. THANK YOU. You saved my life. You showed me what my life could be. You validated Artlife for me, for thousands of lost and confused creatives in the world. THANK YOU. For all the joy you gave me and gave the world. You crazy, creative, restless, manically depressive, genius, art-making animal, machine, angel, devil, sprite, and hummingbird. I love you and I’ll miss you forever.

My Daniel Memory That I Haven’t Written About a Million Times Already

Kathy McCarty (close friend and collaborator): Once Daniel got to Austin, a true guitar town in every way, he decided to abandon the piano, which he could actually play quite well, with an almost instinctive touch, and play guitar instead. I discouraged him from this because it just seemed so dumb to me. Why play guitar in a town with a zillion amazing guitarists? Guitar is covered! And Daniel was so bad at playing the guitar. He was even worse than I am at tuning a guitar (in fact, it was not even close. I can actually tune a guitar if I really set my mind to it, and he simply could. Not. Do. It) and was horrible at playing even the simplest chords. Unlike many other people, I am not going to sugarcoat it. Daniel was a dreadful guitarist.

But one thing that Daniel had right about being an artist was not caring what anybody else thought. He did what he wanted to do. He never ever did anything he didn’t want to do, as far as I know. The absolute worst way to try to do a creative project with Daniel was to have an idea of what you wanted him to do. And God forbid you tell him what you wanted to do, because he would never ever want to do anyone else’s idea. This is actually a good thing for an artist to be like because you need this skill, the skill of not caring what other people want you to do and not caring what they think, in order to forge your own way. So Daniel switched from piano (which he played beautifully) to guitar (which he did not).

But he would still play the piano for me. I had a job at the Old Pecan Street Café on 6th Street, and one job I had there was making crêpes. I would go to the deserted banquet-room kitchen upstairs of the restaurant at odd times, like 4 in the afternoon or 10 at night, when it wasn’t being used for a banquet, and I would make 300 to 400 crêpes. It took about two hours, and I would stack the crêpes on cardboard bakery circles. I would have three crêpes pans going at once. There is a film out there of me doing it somewhere; a Glass Eye short “meet the band” kind of thing. It was a job that required a certain amount of skill, but once you had it down (I did it for more than a decade), it was rather dull. (It was piecework though, so it paid well! I think I made $15 an hour doing it.)

So Daniel would come with me to the banquet kitchen, and we would roll the piano in from the banquet room (an old upright). While I would make crêpes, he would play all my favorite Daniel Johnston songs for me. It was absolute bliss. My No. 1 tune was “Living Life,” but other Daniel Johnston piano hits he would play for me included “Going Down,” “Monkey in a Zoo,” “Wicked Will” (which I found silly), “Premarital Sex,” “Love Defined,” and “I Had a Dream.” Sometimes he wouldn’t feel like being my personal jukebox, and he would just write new music, improvise, and be silly.

These were probably the best times we had. Now I feel like they should put a plaque in that building, saying, “This Is Where Daniel Johnston Played Piano and Improvised Songs for Kathy McCarty.”

Daniel went on to win the Best Guitarist Award in the Austin Chronicle Music Poll. There are hot-shot Austin guitarists who still feel the burn of that one, because yikes! It was like a Three Stooges slap in the face to a long line of guitarists. Like a hand trailing down a line of people slapping one after the other with the same motion. Like someone dragging a stick across a picket fence.

‘If I Die First, I’ll Haunt You’

Kramer (Shimmy Disc founder): The first thing Daniel Johnston ever said to me was, “Do you believe in the Devil?” This was in 1988. He’d just arrived at my recording studio, Noise New York. Jad Fair was with him. I said, “Hi, Daniel. I’m so happy to finally meet you.” “Do you believe in the Devil?” he asked.

The plan was for Daniel to come to NYC with ten brand-new love songs and together we’d create the greatest record ever made. “Better than the Beatles!” Daniel would say on the phone, as we chatted in the weeks prior to his now-infamous first trip to NYC. “Better than the Beatles! Absolutely!” I’d reply. Then we’d laugh. But instead of ten new love songs, Daniel arrived with a head full of chattering voices, a paranoiac glow that seemed to grow brighter by the hour, and a notebook filled with gospel songs. Songs of the Devil. He also brought two love songs. One was “True Love Will Find You in the End,” which he sang and played with such an enduring sense of eternal love, such longing, such purity, such clarity and optimism. He was having a great day.

But then, the day began to change. Daniel started to behave oddly. He started hearing voices. I could almost hear them myself, ricocheting around inside his head, his body, his soul. A sense of urgency soon flooded me. So I pushed him to the piano, stuck my best microphone in front of him, and tried to begin work on the only other love song he said he could do, “Some Things Last a Long Time,” a collaborative composition written by Daniel and one of my dearest friends, Jad Fair. Once or twice in my career as a record producer, I might hear a song that left no doubt in my mind, no doubt whatsoever, that if everyone in the world could hear it at the same time, the entire planet would weep — that everyone would instantly forgive each other and themselves for all their respective past and future wrongs, and instantly arrive at the realization that the only thing that matters is love. And then the world would change. This was one of those songs.

But Daniel, poor Daniel, he couldn’t make it past the first verse. He just couldn’t play the chords right on the piano, and he couldn’t sing more than a couple of lines before the tears arrived. That’s when I started crying, too. “Dan, you and Jad go get lunch. I’ll play the piano myself while you’re gone, and when you get back, you can do just the vocals. It’ll sound beautiful. Don’t worry. Go. Take a break.” “God Bless me,” he cried, and left for lunch. But he never came back.

Three days later I found Daniel standing in front of CBGB’s, which was right next to a homeless shelter, under a light autumn rain. He was hyperalert, like a wounded fox, and he caught sight of me as I crossed the street toward him. “Kramer! You have to give me some money! I don’t have any money left and I’m really hungry! I haven’t eaten in days!” I gave him a $20 bill, at which point he turned instantly, rushed up to an old homeless man lying on the sidewalk and pushed the $20 into his palm. “This is for you. God Bless me! God Bless me!” he cried.

I can’t quite recall exactly how I did it, but I somehow got Daniel back to my studio, and somehow, despite the tornadoes raging inside his head, he began to sing. It was stop and start all the way, and there were a couple of lines he just couldn’t get right. Words were missing. After a few retakes, and seeing that each one was inferior to the last, Daniel put his coat on and left. I wondered if I’d ever see him again, and in a billion years I can never accurately describe what a terrible feeling that was.

In the days that followed, I sang a chorus of voices beneath where those missing words ought to have been, and I added some sounds I felt might invoke the specters of those memories that Daniel and Jad’s lyrics were clearly trying to convey. This is the very soul of Daniel Johnston, I said to myself. This song, this one song, is the perfect audio reckoning of everything his songs meant to me, and as I hoped with all my heart, to everyone.

We hadn’t managed to record enough songs to flesh out a full-length LP, so I worked with Jeff Tartakov to find some previously unreleased “field” recordings that I felt would compliment the songs we already had, and in the end, those songs we recorded at Noise New York, along with some live recordings from CBGB’s in NYC and Pier Platters in Hoboken, became the LP Daniel titled 1990.

Thirty-one years later, I stood over Daniel’s casket with Jeff and Don Goede, who’d accompanied Daniel for so many years on so many tours, sharing so many hotel rooms with him, so many meals, so many tears, so much pain, and so much joy. I was about to tell them about how, over the course of 30 years of friendship, Dan and I would joke about which one of us would die first. “Hey, Kramer! If I die first, I’ll haunt you, but you gotta promise that if you die first, you’ll haunt me!” But just as I was about to tell that story, Don Goede told it himself. “Dan and I used to joke about who’d die first. Who’s gonna haunt who …”

That evening, after the funeral, Jad Fair and I sang “Some Things Last a Long Time” at a small gathering of friends and fans, as Danny’s ghost stood behind us, and before us, and all around us. And that will last forever.

Number One

Jeff Feuerzeig: So it’s the year 2000, and producer Henry Rosenthal and I land in Waller, Texas, to start principal photography on what will become The Devil and Daniel Johnston. And we quickly learn that Daniel is very difficult to work with. It’s not totally his fault due to his condition (and the arsenal of psych meds that his doctors have him on). But as confirmed by his longtime Kent State Art School best friend from East Liverpool, Ohio, David Thornberry, “Part of Daniel’s art is to provoke by using everyone around him as chess pieces in the theater of his mind” — which is just a polite way of warning us that Daniel is a total pain in the ass. His long-suffering elderly mom and dad concur, and it becomes evident that care-taking for someone with long-term mental illness is no walk in the park.

Regardless, we are determined to collaborate with Daniel and tell his inspiring and harrowing story no matter what it takes because we believe beyond a shadow of a doubt that this guy is the GOAT. We’re talking Muhammad Ali, the undisputed heavyweight champ when it comes to songwriting and art. No hyperbole, right up there on the Mount Rushmore of greats like Dylan, Lou Reed, Brian Wilson, and Andy Warhol. And it should be noted that few others at this time agree with our assessment. Furthermore, the idea of spending $1 million to tell the Daniel Johnston story is greeted almost universally like Fulton’s Folly. But as the saying goes, “If you build it, they will come.” So we persevere.

Now how did Henry and I arrive at this at-the-time much-maligned opinion? It’s all contained on the 14 basement and live-recorded Stress Records cassette tapes and one studio album titled 1990, produced by Kramer, that Daniel left in his wake. (These are now readily available for your appraisal on Spotify and Apple Music.) This voluminous body of work — where Daniel accompanies himself on piano, Magnus chord organ, and acoustic guitar — is overflowing with heartbreaking tales of unrequited love about a girl named Laurie who married an undertaker. The other half features unfiltered biographical chronicles of his manic depression set to a catchy melody. These lo-fi ditties highlight an overabundance of joy, numerous comic bits, and his secret weapon — limitless humorous turns of phrase. The latter has been largely overlooked in his story.

So back to the matter at hand: scheduling a Super 16mm documentary film crew, which is challenging at best. We learn from day one that Daniel sleeps all day and stays up all night in his dad’s garage turned art studio. It’s here where he chain-smokes as he hammers away on his dilapidated piano, filling scads of notebooks and both sides of 90-minute cassette tapes with new songs. He also makes stacks of drawings populated with an imaginary cast of characters he’s created. The guy is the definition of prolific, a one-person art machine. When he takes a break, it’s only to listen at full volume to his beloved Beatles — Beatles bootleg LPs, Paul McCartney and Wings, John Lennon and Yoko, Ringo, George Harrison solo LPs, and the Rutles. More on this later.

So we quickly adjust and go with the flow. And every day is literally like the Harold Ramis/Bill Murray movie Groundhog Day. Daniel rises like clockwork at 4:30 p.m., cheerfully welcomes Henry and me with the exact same greeting, then insists on going to Ernesto’s, the only Mexican restaurant in town. He orders a giant iced tea, unscrews the silver top of the glass sugar dispenser, and pours its entire contents into his giant red plastic cup. Daniel then guzzles this diabetes bomb down in one swoop, spilling quite a bit on his ever-present stained T-shirt. Moments later, he conks out cold from his glucose rush with his head on the table while the crew and I eat our meals. What heroin was at one time to Lou Reed, sugar is to Daniel Johnston.

Then it’s off to the PennySaver store where Daniel demands we buy him some stickers (he loves to shop). And then a final stop at the local Sonic Drive-In for a 44-ounce Blue Raspberry Slush for an additional 760 calories. So by the time night falls, more than a few precious hours of shooting time has already been killed, and no film has yet gone through the camera. But like Werner Herzog said, “Documentary filmmakers are thieves, who get away with loot from the most beautiful, scary, and spectacular places you can ever find.” And Bill Johnston’s garage turned art studio for Daniel fits Herzog’s description to a T.

It’s inside this magical art cathedral where we chance upon multiple 30-gallon Hefty garbage bags, sadly resting below an old, oil-leaking lawn mower. We are giddy as we sift through stacks of yellowed notebooks overflowing with Daniel’s art, song lyrics, diary entries, and intricate flip-page animated films. Another garbage bag contains hundreds of cheap 90-minute cassette tapes that Daniel has filled with countless finished and unfinished lost songs. In a damp bedroom closet, we discover many reels of Daniel’s forgotten Super 8mm comedic home movies, the film’s emulsion being eaten by mold.

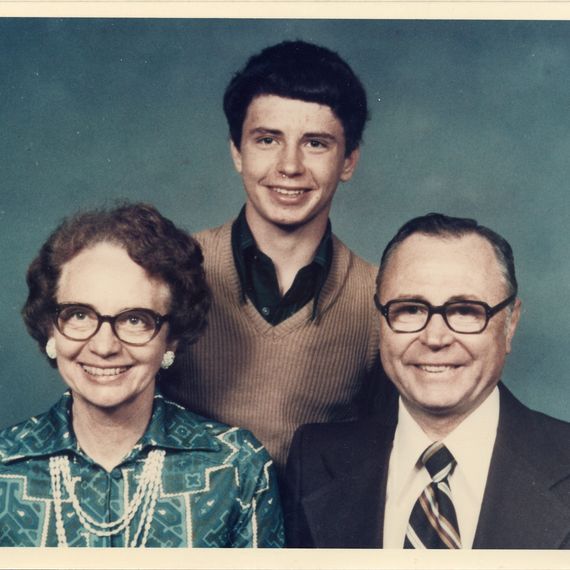

Our mission was clear, to excavate the work of this important artist and save it from the garbage dumpster of history, where the Hefty bags indicated it was heading. At this point, the Johnston family (except for sister Margie) were not in agreement as to the quality and merit of Daniel’s art and music. They told me they found its occasional high praise in underground circles puzzling at best. Regardless, the hundreds of fan letters Daniel received from around the world were an acknowledgment — to at least Bill and Mabel Johnston — that many people were emotionally touched by Daniel’s unique work. So despite their own aesthetic opinions, they were very proud of this fact.

Flash-forward to 3 a.m. on one of many all-nighters in Daniel’s garage. The crew — after another failed attempt at getting a coherent interview out of Daniel — has been sent back to the Super 8 Motel. But Henry and I are not ready to throw in the towel, so we stick around with just my Super 16mm Bolex camera. Daniel sparks up a “Happy Smoke” and starts blasting the Rutles All You Need Is Cash LP, and nothing on planet Earth could sound better. Listening to the Rutles with Daniel Johnston in the wee hours of Waller, Texas, is the very definition of fun. It’s like being back in high school. And through Daniel’s filter, it becomes clear as a bell to me that the Rutles are every bit as great as the Beatles.

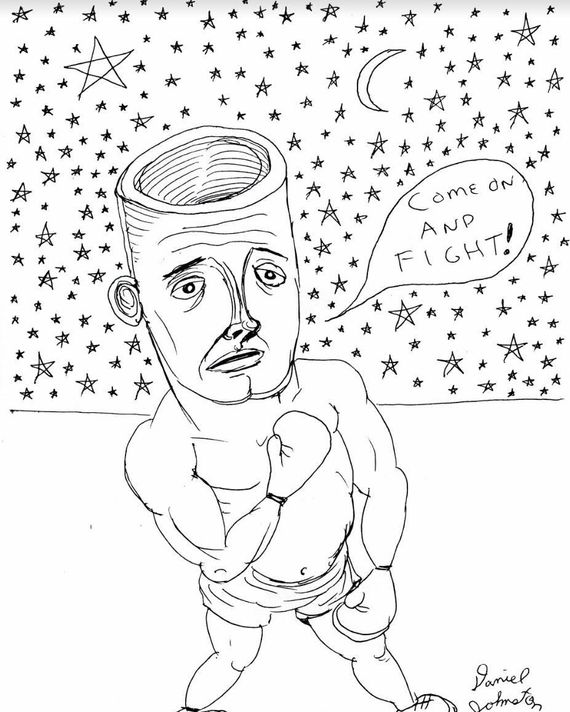

The song “Number One” comes on and Daniel starts dancing. Inspired, I grab my Bolex and start yelling out direction over the Beatles-esque rock-and-roll melodies of Neil Innes. Daniel and I are both big fans of dance crazes. And Daniel proceeds to do a series of interpretive dances of his entire life as I charge at him with my camera. He does “the Propeller” spinning wildly, symbolizing his plane crash; “the Jackie Gleason” with high kicks in the air, symbolizing his physical comedy; “the Devil Dance” with his fingers extended like Devil horns, expressing his years of obsession with Satan; “the Straitjacket,” symbolizing his multiple spells in the mental hospital; and “Joe the Boxer,” my favorite of his characters, delivering a rapid combination of shadow blows and a final devastating knockout punch.

This was Daniel’s personal gift to me, and as Henry and I left that garage at 5 a.m., I was elated. I knew this was the single best piece of film I would ever shoot. It can be seen edited to Daniel’s song “Held the Hand” as the haunting end title sequence of The Devil and Daniel Johnston.