Ellen T. Harris

This guest post is the third of an occasional series of guest posts by external researchers who have used the Bank of England’s archives for their work on subjects outside traditional central banking topics.

George Frideric Handel was a master musician — an internationally renowned composer, virtuoso performer, and music director of London’s Royal Academy of Music, one of Europe’s most prestigious opera houses. For musicologists, studying his life and works typically means engaging with his compositional manuscripts at The British Library, as well as the documents, letters, and newspapers that describe his interaction with royalty, relationships to others, and contemporary reaction to his music. But when I began to explore Handel’s personal accounts at the Bank of England twenty years ago, I was often asked why. For me the answer was always ‘follow the money’. Handel’s financial records provide a unique window on his career, musical environments, income, and even his health.

His early career

Inculcated with business savvy by his father (a courtier, barber surgeon, and wine dealer), Handel had already made a name for himself in Germany and Italy when he arrived in London in 1710. Earlier that year, at the age of twenty-five, he had been appointed Master of Music at the court of Hanover, but he was given leave to reside for long periods in England. A blip in his employment relating to Hanoverian displeasure with the Peace of Utrecht in 1713, and Handel’s celebration of it in the Utrecht Te Deum and Jubilate, allowed the composer to slip into the service of Queen Anne. She provided him with an annual pension of £200 (£25,000 at today’s prices), a handsome benefit George I immediately continued following the Hanoverian Succession.

The bursting of the South Sea Bubble

By at least mid-1715, Handel had the wherewithal to purchase £500 of South Sea Company shares, as we know from a note signed by him and dated 13 March 1715/16 that asks his dividend, being ‘Fifteen pounds on Five Hundred pounds, which is all my Stock in the South Sea Company books & for half a Year due at Christmas last’ (that is, Christmas 1715), be paid to a Mr Phillip Cooke’ (see Documents 1: 334). Thereafter the shares climbed sharply in value, before crashing in 1720 in one of the famous bubble episodes in financial history – the South Sea Bubble. Three years later, in a final resolution of the crisis, South Sea shareholders saw their accounts split 50/50 between equity shares in the company and annuity stock held by the Bank of England. The account opened for Handel at the Bank with £150 of South Sea annuities shows that he must have been holding £300 of shares at the time of the split (AC 27/6443, p. 122).

But one must work backwards through the succession of dividends offered to shareholders after the Bubble burst (10% dividend on 25 June 1720; a 1/3 stock dividend in September 1721; and a 1/16 stock dividend in April 1723) to ascertain that Handel owned either £150 or £200 of shares when the Bubble burst (SSC Court of Directors Minutes, 13 June 1721 and 29 March 1723, and Statutes at Large Vol. 15, 9 George I, Ch. 6). The exact number would depend on whether Handel purchased or sold stock at each dividend to make his account balance end with 50 or 00, as was officially encouraged.

Overall, Handel timed his market moves fairly well and did not lose money from his holdings of South Sea stock. He sold at least £300 of shares before the crash as the stock was rising (presumably at substantial profit), holding only £150 or £200 in shares at the time the Bubble burst in 1720, and, after the dividends and 50/50 division between equity shares and the new annuity, was still holding £150 in shares in 1723. He must have come out even or ahead when he ultimately sold his holdings. Unfortunately, the longevity of the account and thus its final value cannot be known due to the destruction of the South Sea ledgers in the nineteenth century.

Cashflow management

Handel held his account in South Sea Annuities at the Bank of England from 1723 to 1732, and it is the activity here that tracks Handel’s finances during those years. Unlike Handel’s shares in the South Sea Company, the account in annuities was no investment for Handel. Rather, he treated it like a cash account. Additions of stock were sold after relatively short intervals, sometimes leaving the account empty for months at a time (AC 27/6443). In Courting Gentility, I initially accounted for this pattern in terms of Handel’s financial needs as a cash-strapped individual who needed to sell quickly and without an eye on the market. But this explanation only refers to the speed with which money was withdrawn and not to why Handel maintained the annuities account for so many years without letting any capital accrue. The answer to this question appears in a 5% Bank Annuity Handel held in 1721.

It would be easy to disregard Handel’s account in 5% Bank Annuities given that it existed for only two days. Opened on 11 October 1721 with £200 of annuities, it was closed out on 13 October when Handel sold the entire stock (AC 27/348, p. 209). This would seem inexplicable without an understanding of the origin and purpose of the annuity itself, namely that Parliament established it for the purpose of raising funds to pay the arrears on the Civil List, including ‘fees, salaries, wages, pensions, annuities or other certain or extraordinary allowances’ (Statutes at Large Vol. 14, 7 George I, Ch. 27 and Vol. 14, 8 George I, Ch. 20). Walter Chetwynd, Paymaster General of his Majesties Pensions, opened an account with £30,000 of government IOUs (tallies of pro) and used the fund to pay pensions — including the £200 to Handel that represents his full pension for the previous year. Receiving annuities instead of ready money, pensioners were put in to the position of selling their shares to obtain cash. Although the conversion rate from annuities to cash varied, the recipients seem not to have minded, most selling their stock in a matter of days (15% of them on the same day).

Salary Payments

This early use of accounts at the Bank for ‘direct deposits’ explains the pattern of credits and withdrawals in Handel’s later South Sea Annuities account. The annual credits of £700 into this account do not represent purchases of stock that he inexplicably turned around and sold, but direct deposits of his salary that he cashed. At the establishment of the Royal Academy of Music in 1720, Handel had been appointed ‘Master of Musick with a Sallary’ (Documents 1: 450), but the amount is not documented. The annual pattern of deposits in his South Sea Annuities account gives us that answer. In some years, Handel receives the £700 in a single credit (27 September 1726, 4 June 1728, 11 May 1732). In most years, however, the £700 is broken up into as many as three payments, indicating the frequent necessity for the opera company to pay out salaries piecemeal as cash became available. No connection can be drawn between the quality of the product and the company’s solvency. In the 1724-25 season, the Royal Academy produced Handel’s Giulio Cesare, Tamerlano, and Rodelinda among other works, but it had to space out the payment of his salary over three instalments, beginning in July but only completed on 23 November, exactly one week before the opening of the next year’s season.

By 1728, the Royal Academy of Music ran out of funds, but Handel was determined to move ahead in collaboration with the impresario John Jacob Heidegger. Perhaps this was a pipedream, but at least initially Handel’s salary did not change. However, financial difficulties soon caught up with this ‘Second’ Academy, and the closure of Handel’s South Sea Annuities account on 22 June 1732 (AC 27/6456) suggests that the payment of his salary by deposit (and perhaps the payment of the salary at all) had become unsustainable.

Handel sold the £2,450 of South Sea Annuities he had accumulated, took out some cash, and opened a cash account at the Bank with the remaining £2,300 (C 98/2608, p. 2674). In this account one might reasonably expect the in-and-out that was the pattern in the South Sea Annuities, but over the seven years of the cash account there are no further deposits. Rather, Handel withdraws a decreasing sum of money each year (sometimes in multiple transactions) until a final withdrawal of £50 on 28 March 1739 closes the account (C 98/2643, p. 2270). Perhaps nothing could provide a better depiction of the weakening financial state of opera in London during the 1730s than that Handel, despite providing such major works as Ariodante, Alcina, and the English oratorio Athalia, all of which received their London premieres in the spring on 1735, could make no deposits at the Bank. The composer held no accounts whatsoever at the Bank between 1739 and 1743, but he persevered with opera until 1741. Later that year he quit London for Dublin, where he presented two subscription series and premiered Messiah.

Return to London

When Handel returned to London in 1742, he was done with opera but only at the cusp of his wealth from the presentation of English oratorio. After the premiere of Samson in February 1743, he opened a new account in South Sea Annuities in May (AC27 6471, p. 54) and a new cash account in 1744 (C98/2657, p. 2746).

From this date Handel put his proceeds into the cash account, moving large sums into his varied stock portfolio when he was sure of his profit. With just two exceptions between 1743 and his death in 1759, Handel’s stock accounts only grew, his new purchases averaging £1,100 per year. Handel died a rich man holding £17,500 in 3% annuities at the Bank of England (AC27/6702, p. 2646), just under £2.2 million at today’s prices.

Beyond their importance for the financial information they contain, Handel’s accounts at the Bank of England also provide unexpected insight into his personal wellbeing. The preservation of his signature from 1721 to 1758 documents a marked deterioration in his eyesight and failing health during the final decade of his life.

Handel’s signature on Bank of England transfer forms 1721-1758

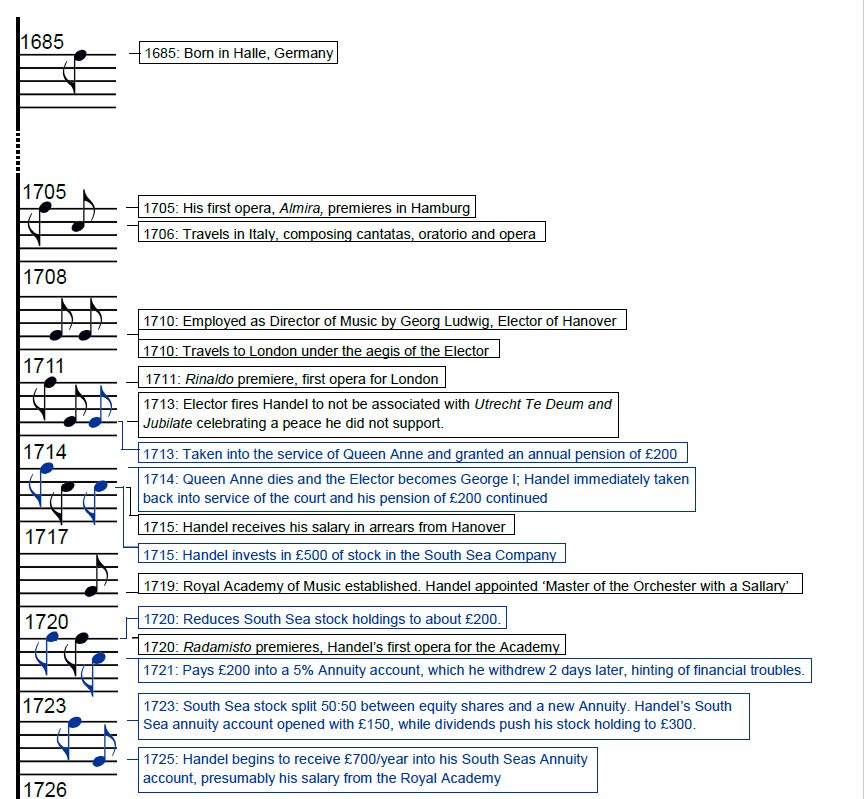

A timeline of key financial events (in blue) and other key events in Handel’s life and career

Ellen T. Harris is Professor Emeritus in Musicology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. A detailed exposition of the materials presented here is forthcoming in Ellen T Harris, “ ‘Master of the Orchester with a Salary’: Handel at the Bank of England” in Music & Letters 101 (2020).

If you want to get in touch, please email us at bankunderground@bankofengland.co.uk or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Dear Sirs,

today´s contribution to BankUnderground on Georg Friedrich Handel and the Bank of England made my day, and I will read it again over the weekend.

It will also nudge me to re-read Neal Stephenson´s “Baroque Cycle” which covers the same historical epoch, eloquently describes origins of the Bank, and even mentions Handel on occasions.

Kudos to Professor Harris!

Sincerely,

Radek Urban, your regular reader

This is a lovely post and excellent research. Kudos to all involved and to the Bank of England.

Wow, excellent research!

Professor Harris, I wonder if you watched the Farinelli movie. I am sure it took generous liberties with the historical details, but makes great use of Händel’s music.

Fascinating piece. Thanks.

Fascinating article. Thanks for sharing your research.

What caused the destruction of the South Sea ledgers in. The nineteenth century?

I have a copy of Georg Haendel’s last will & testament.

Congratulations on this fascinating blog post! The change in Handel’s fortunes when shifting from opera to oratorio is impressive.

Like Ms Mitchell in an earlier comment, I too would be interested in information about what happened to the ledgers of the South Sea company in the 19th century.

Again, many thanks for this piece.

To Evelyn Mitchell and Boris Cournede: I cannot provide documentary detail, but whether it was by intent or neglect, no South Sea Company ledgers survived the disestablishment of the company in 1853. However, the ledgers pertinent to Handel’s investments, and much else, may already have been lost in the fire that consumed the Old South Sea House in 1826.

To Kurt Thomas: The Farinelli movie is largely an ahistorical fantasy, but I agree that the music can be ravishing. The performance of “Lascia, ch’io pianga” from Rinaldo, despite being transferred from the prima donna role of Almirena to Farinelli in the supposed role of Rinaldo, is revelatory, using ornamentation from a keyboard transcription of the aria not previously considered vocally derived. The movie changed that.

Thank you for both the article and the information on the movie!