A train pulls into Hoboken Terminal. Commuters swarm the dim, dusty platform, then disperse, gone as fast as they came. The train disappears, too, back toward Manhattan, and a quiet settles in. A few people remain—a geriatric black man in a sweat suit and sandals, seated on a weathered bench; two potbellied white guys in oversize football jerseys, leaning against a concrete column; a handful of others—and all of them are staring at their phone. They may be strangers, but they belong to the same tribe. These are the carpetbagging gamblers of the Garden State.

They’re not alone. The bettors enter this promised land anywhere along the 108-mile border between New York and New Jersey. They come down Route 17 to Mahwah, order disco fries at the State Line Diner, and wager. They cross the George Washington Bridge and bet in the KFC parking lot in Fort Lee. Some just pull over to the shoulder, whip out their phone, then U-turn back over the bridge. “I know people who drive to the Vince Lombardi rest station just to make their bets,” Chris Christie told The New York Times in June, “and then turn around and go back to the city.” In 2003, the pit stop was described by a trucker to The New Yorker’s John McPhee as “a real dangerous place. Whores. Dope. Guys who’ll hit you over the head and rob you.” Today, the trucker might add to his list the gamblers.

Speaking of Christie, he’s no idle observer; he’s the architect, and this is a valedictory moment years in the making. In 2011, the then governor of New Jersey nobly launched the battle to legalize sports betting in his state. Why shouldn’t the government get a piece of the $150 billion wagered illegally on sports each year, as estimated by the American Gaming Association? His efforts paid off when, in May 2018, the Supreme Court overturned a 1992 federal law that had banned the practice in all but a few places. New Jersey was among the first states to take advantage, accepting its first bet within a month of the high court’s ruling. Two, actually, each twenty dollars, placed by its current governor, Phil Murphy, on the New Jersey Devils to win the 2019 Stanley Cup (they didn’t) and on defending champion Germany to win the World Cup (they were eliminated in the first round). Christie earned his rightful spot in the Sports Betting Hall of Fame, which is a thing, apparently. Since then, sixteen more states have passed such bills, including New York. None of them come close to New Jersey, which took in nearly $3 billion in its first year of operations. This past May, it surpassed Nevada to become the state in which the highest amount was bet on sporting events—nearly $320 million in that month alone. Why such success? Is it something in the waters of the Ramapo? Perhaps. But also, the state allows you to bet on your phone. Other states have been reluctant to embrace the practice in an effort to drive gamblers toward the traditional brick-and-mortar houses of sin, like casinos and racetracks. Their mistake: In New Jersey, mobile betting accounts for a whopping 82 percent of the state’s overall handle.

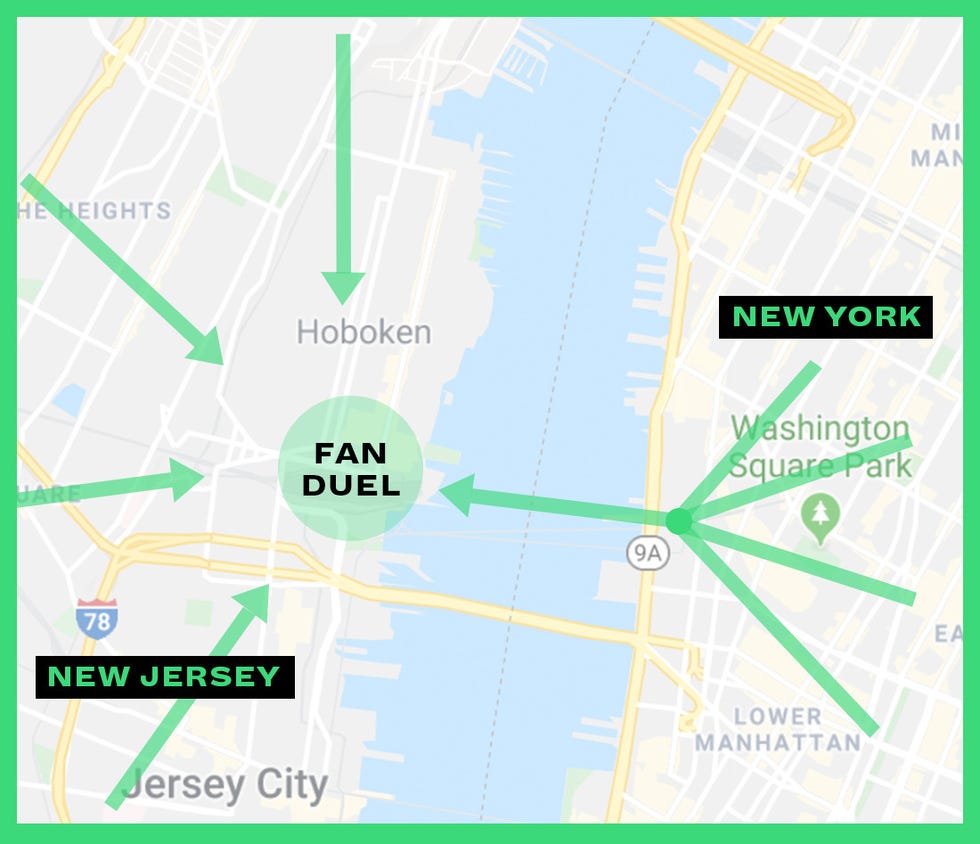

You don’t need to be a resident to bet in New Jersey; you just need to be at least twenty-one. But you must be within its boundaries when your bet is placed. Out-of-staters have tried everything they can to get around these restrictions: deploying virtual private networks (VPNs) that mask users’ IP addresses and therefore their location; trying to place bets from the Staten Island Ferry on its journey across New York Harbor; standing atop the Tri-States Monument in Port Jervis, their phones held high and oriented southward. Nothing has worked, thanks to the efforts of the aptly named GeoComply, which is licensed by the New Jersey Division of Gaming Enforcement to ensure all bettors comply with the state’s geographical requirements. The company claims that in many cases it can locate users to within a few meters. Anecdotally, I can confirm. FanDuel, the most popular betting app in the state, pinged me while I was in the dead center of the Lincoln Tunnel, a hundred feet underwater and halfway between New York City and Weehawken.

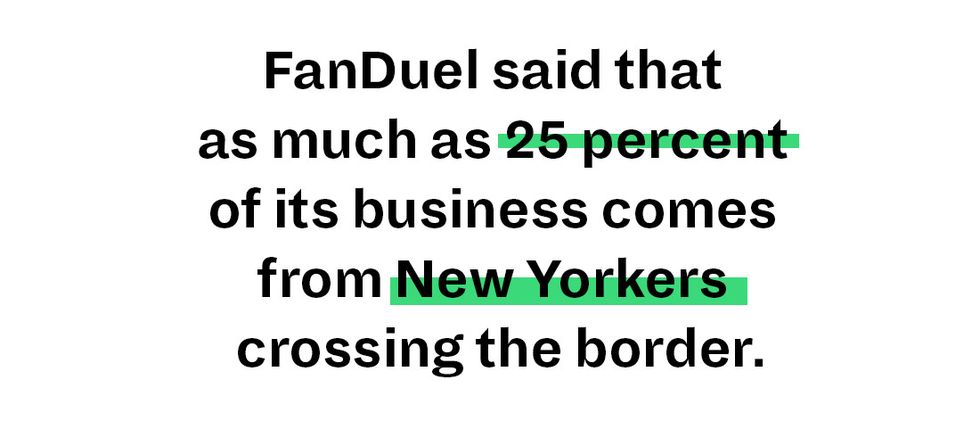

Which is why New Yorkers are flooding west. But not too far west—44 percent of all mobile bets in New Jersey are made within two miles of the state border, according to GeoComply, with 80 percent made within ten miles. At a public hearing in May, FanDuel’s COO said that as much as 25 percent of its business comes from New Yorkers crossing the border. For those carpetbagging gamblers without a car, Hoboken Terminal—which couldn’t be closer to the state border without falling into the Hudson River—is a mecca.

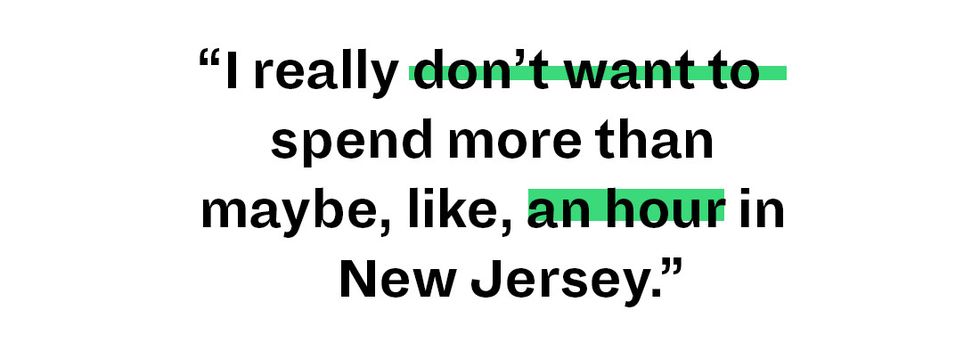

As it changes them, so they change it: The gamblers step onto the platform and transform it into a literally underground betting parlor. The Borgata it isn’t. But convenience beats out coddling. Here, you won’t find leather seats at ritzy bars, nor giant television screens and waitresses showing too much skin. Here, in this dusky underworld, the house is open all day and all night, and it’s less than twenty minutes from midtown Manhattan. Here, you can get cell service without leaving the turnstile, so the whole trip costs the price of a one-way fare. “I really don’t want to spend more than maybe, like, an hour in New Jersey,” says Harrison, twenty-seven, from Queens, one of the many carpetbagging gamblers I spoke to over the opening weekend of the NFL’s 2019 season.

Some land here by trial and error. “I didn’t know where you could pick up signal, so I just took the train to Jersey City,” says Cooper, forty, who lives in Brooklyn. Rookie mistake. “So I got out of the station and still couldn’t get signal. I was literally walking around on a Saturday night in Jersey City looking for signal.” He kept searching, because what was once off-limits by law is now welcome. “I spent twelve years in the military, and I never wanted to get myself into any trouble, so I never had a bookie and didn’t do anything illegal. It was always in Vegas.” He found Hoboken Terminal and its solid cell service, where he can fulfill a longtime wish without fear of repercussion.

For others, the convenience is a liability. Earlier, I met Chris, twenty-eight, a SoundCloud rapper who goes by “Cristo from the Bronx.” He’d figured out the way to save the return fare all on his own, along with the cell-reception issue at the Jersey City station. Now he can come place bets whenever he feels like it, and he feels like it most strongly when his previous bets “are going left.” I ask him to explain. If he’s back home, watching a game unfold, and he knows he’s losing, “I’m like, Oh, hell no, I’m not trying to lose four hundred bucks today. Let me go back and bet it back.”

Shortly after, I meet Dylan, twenty-nine, a political-campaign operative from upstate New York who shares Chris’s instinct. He’d already made the trip to New Jersey earlier in the summer to place his NFL bets for the season, but after A. J. Green, wide receiver for the Cincinnati Bengals, sustained an injury in training camp, Dylan tells me, “I ended up back out here on a Sunday morning to change all my bets.” He admits, “I definitely bet more now than before.”

With the betting scene now legal and regulated, the range of bets has expanded. I approach a guy in a neon safety vest who’s furiously typing away at his phone. Ahmed, thirty-seven, from Peekskill, New York, is on his lunch break and looking to make it big on a parlay, the Hail Mary pass of sports bets, in which the gambler picks the winners of several games. The odds are much lower, so the payouts are much higher, which is why local bookies don’t like taking parlays. “They don’t want to take that risk,” Ahmed says. “The biggest parlay you could do with a bookie was four teams. The biggest parlay you can do with these guys is fifteen.” Ahmed has a magic touch for them. “I had a nine-team parlay last year for twelve grand. Two weeks after that, I had an eight-team parlay for ten grand.” Lunch hour’s nearly over, so he excuses himself to enter his bets, then he’s gone.

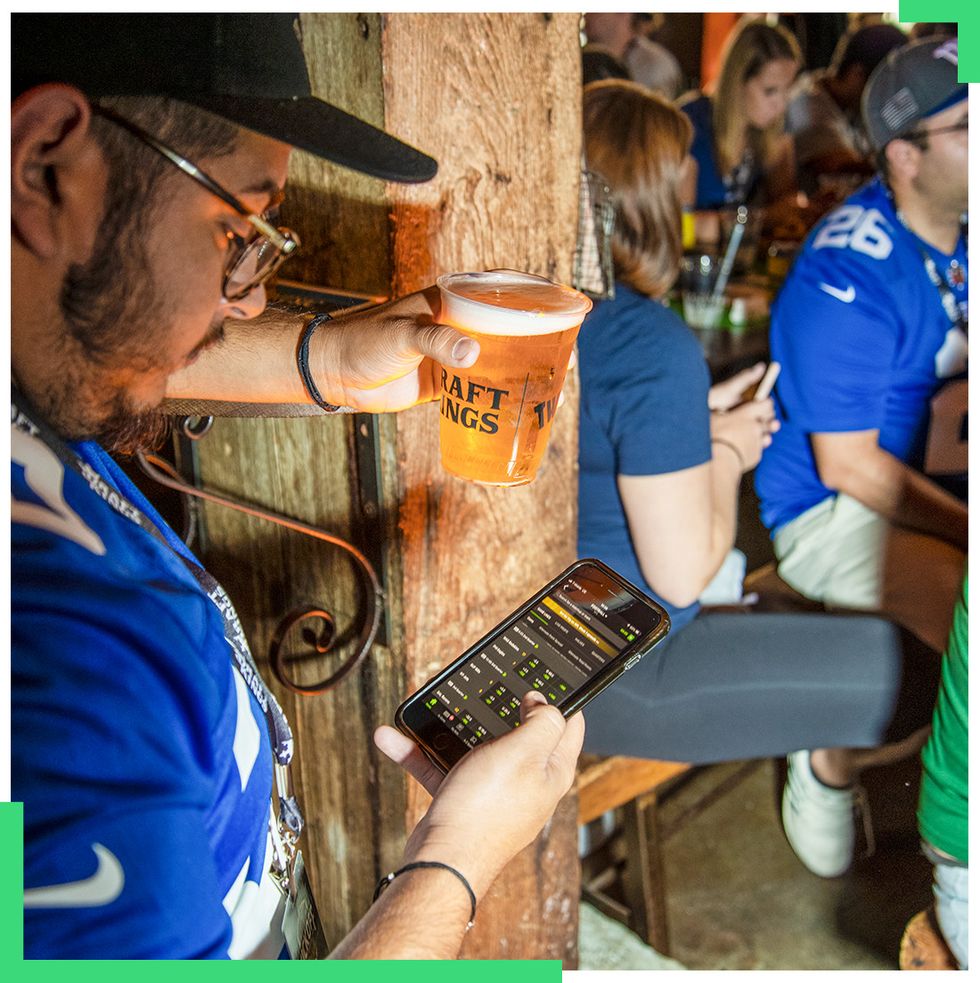

Three days later. It’s the first Sunday of the NFL’s regular season. Thirteen games are on the schedule, which means twenty-six teams are playing, which means the betting opportunities are aplenty. DraftKings, the second-most-popular mobile-betting operator in New Jersey, has decided to make an event of it, holding a pop-up party with a few former NFL players at a bar not far from Hoboken Terminal. The vibe is upbeat, though contrived. Maybe it’s the cost—fifty dollars, unless you’ve been designated one of the app’s VIP players—or the company: Guest appearances include legitimate onetime star Donovan McNabb as well as Rashad Jennings, whose career on Dancing with the Stars is more distinguished than his career in professional football. Or maybe it’s an issue of convenience: Why bother going to a party to place bets when you can do so from your phone?

Ali, twenty-nine, like several attendees I meet, is a carpetbagging gambler. “It’s just annoying that we can’t do it in New York,” he shouts over the din of four games blaring from four television screens. “It’s stupid.” Until that changes, he’s limited by the vagaries of geography and time. “Unfortunately, I can’t bet weekly, because I don’t have the time to come in every week.” (Ali, like everyone else I spoke to for this story, despite my best efforts to find otherwise, is a man.) I head back to Hoboken Terminal. There, on the platform, gamblers abound, though not all are willing to talk. Nick, twenty-eight, from Queens, explains: “It”—gambling—“has that negative stigma behind it, you know, where it’s like you’re a degenerate, you’re a shitty person and whatnot.” (Say what you will about sports betting’s morality, but placing bets has never been illegal. It’s taking them that was banned.) He learned to bet from his father. “Other kids throw a baseball in the backyard with their dads, or they’re into cars or fishing. With me and my dad, it was always, What’s the line on this game?” Nick, hopeful that public sentiment is shifting, hosts a sports-betting podcast called Veterans Minimum.

The whole ecosystem is changing. ESPN and Fox Sports 1 are already airing shows dedicated to betting. Buffalo Wild Wings is testing a pilot program to roll out sports betting in its New Jersey franchises. Major league teams are investing in technology to bring in-game betting to arenas and ballparks, where one day you may be able to place bets on every pitch or free throw or first down from a screen at your seat. As NBA commissioner Adam Silver argued in a New York Times op-ed in 2014, a landmark moment for the movement, states run—and profit from—the lottery. What’s so different about sports gambling? Silver didn’t spill much ink on the fact that the major leagues and their teams stand to profit from a pot of money previously illegal and out of reach.

What about the fans? How might legalized betting alter their relationships with the sports they love? The ban was put in place for a reason, after all: Those with a financial stake in the outcome have been known to sway a game or two—just ask the 1919 White Sox or the 1978–79 Boston College basketball team. Then again, the ban was never all that effective, as evidenced by anyone who’s ever collected the betting pool for their fantasy-football league. Legalized marijuana hasn’t led to a pothead epidemic, and sports betting is unlikely to ensnare the innocent masses. Those who bet before will keep betting; it’s just that now their wagers will be regulated by the government.

This article appears in the November 2019 issue of Esquire.

Subscribe

And just as marijuana legalization has harshed the mellow of many a weed dealer, it’s the bookies who face extinction. Dirk, a thirty-something who lives on the Upper East Side and works in finance, has been an agent of this particular change. A longtime gambler, he’s stopped placing bets with local bookies. “The bookies miss me a little bit,” he admits. For now, he’s limited only by geography: “If I lived in New Jersey, I’d bet every day.” For mobile sports betting to grow, the industry can’t simply rely on the old guard; it must recruit new users. “Anytime you’re taking an underground market and moving it into a legal and regulated one,” FanDuel’s chief marketing man, Mike Raffensperger, later explains, “it’s an interesting period of transition.” If the stigma persists, it’s time for a rebrand. “We don’t just think of ourselves as a gambling company,” he says. “We think of ourselves as a sports-technology entertainment company.”

DraftKings has laid claim to Hoboken Terminal, if its advertisements on every surface of the station are any indication. “I think I like the idea that I’m not breaking the law,” says Bobby, twenty-nine, from the West Village, who’s sitting on a bench with his dog curled at his feet. It’s his first time betting with a New Jersey sports book; he’s using FanDuel, in spite of the ads. (The company received seven times as many bets in New Jersey during this year’s NFL opening week as it did during last year’s.) “I didn’t know what to do with my day, and I was just waiting for the afternoon football games to get going,” Bobby tells me. “I didn’t even know how I would feel spending an hour coming here, betting, and coming back, if I would feel like it was a waste of time.” He pauses to bet fifty dollars on the Kansas City Chiefs, then flashes a sheepish grin. “If I had more important things to do, I wouldn’t be doing this.”