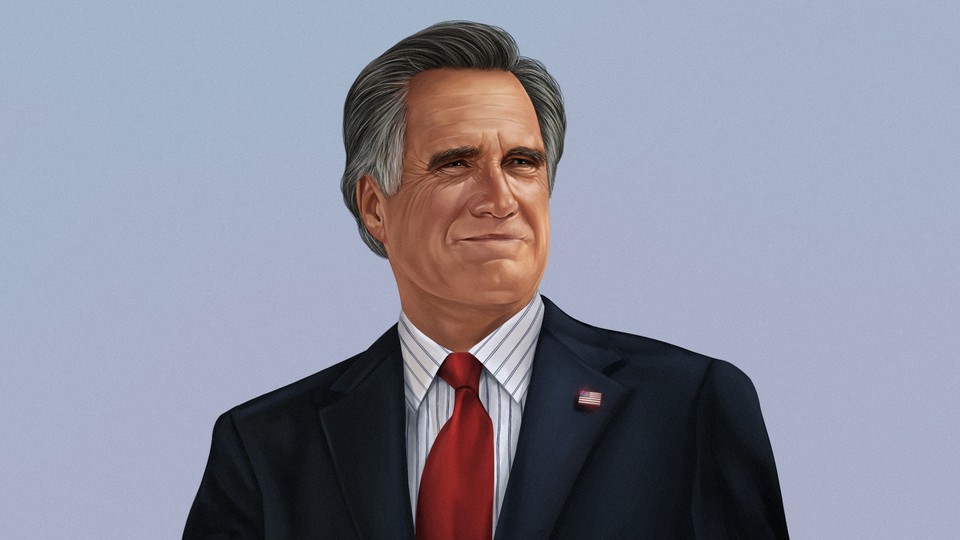

The Liberation of Mitt Romney

The newly rebellious senator has become an outspoken dissident in Trump’s Republican Party, just in time for the president’s impeachment trial.

Updated on October 20, 2019, at 9:32 p.m. ET

Mitt Romney is leaning forward in his chair, his eyes flashing, his voice sharp.

It’s a strange look for the 72-year-old senator, who typically affects a measured, somber tone when discussing Donald Trump’s various moral deficiencies. But after weeks of escalating combat with the president—over Ukraine, and China, and Syria, and impeachment—the gentleman from Utah suddenly appears ready to unload.

What set him off was my recitation of an argument I’ve heard some Republicans deploy lately to excuse Trump’s behavior. Electing a president, the argument goes, is like hiring a plumber—you don’t care about his character, you just want him to get the job done. Sitting in his Senate office, Romney is indignant. “Are you worried that your plumber overcharges you?” he asks. “Are you worried that the plumber’s going to scream at your kids? Are you worried that the plumber is going to squeal out of your driveway?” I am playing devil’s advocate; he is attempting an exorcism.

To Romney, Trump’s performance as president is inextricably tangled up in his character. “Berating another person, or calling them names, or demeaning a class of people, not telling the truth—those are not private things,” he says, adding: “If during the campaign you pay a porn star $130,000, that now comes into the public domain.”

At this, Romney glances over at two of his aides who are watching silently from the other end of the room, and grins. “They’re going, Oh gosh, shut up.”

I’ve spent the past several months in an ongoing conversation with Romney as he’s navigated a Washington that grows more hostile by the day. Before arriving in the Senate, Romney nurtured a pleasant delusion that he could somehow avoid being defined by his relationship with Trump. He had his own policy agenda to advance, his own vision for the future of the Republican Party. He would use his platform to take a stand against Trumpism, while largely ignoring Trump himself. When I would speak with his friends and allies in Utah during last year’s campaign, there was often a certain dilettantish quality in the future Senator Romney they envisioned—a venerable elder statesman dabbling in legislation the way a retiree takes up tennis.

Instead, Romney has emerged as an outspoken dissident in Trump’s Republican Party. In just the past few weeks, he has denounced the president’s attempts to solicit dirt on political rivals from foreign governments as “wrong and appalling”; suggested that his fellow Republicans are looking the other way out of a desire for power; and condemned Trump’s troop withdrawal in Syria as a “bloodstain on the annals of American history.”

Trump has responded with a wrathful procession of personal attacks—deriding Romney as a “pompous ass,” taunting him over his failed presidential bid in 2012, and tweeting a cartoonish video that tags the senator as a “Democrat secret asset.”

These confrontations have turned Romney into one of the most closely watched figures in the impeachment battle now consuming Washington. While his fellow Republicans rail against “partisan witch hunts” and “fake whistle-blowers,” Romney is taking the prospect of a Senate trial seriously—he’s reviewing The Federalist Papers, brushing up on parliamentary procedure, and staying open to the idea that the president may need to be evicted from the Oval Office.

In the nine years I’ve been covering Romney, I’ve never seen him quite so liberated. Unconstrained by consultants, unconcerned about reelection, he is thinking about things such as legacy, and inheritance, and the grand sweep of history. Here, in the twilight of his career, he seems to sense—in a way that eludes many of his colleagues—that he’ll be remembered for what he does in this combustible moment. “I do think people will view this as an inflection point in American history,” Romney tells me.

“I don’t look at myself as being a historical figure,” he hastens to add, “but I do think these are critical times. And I hope that what I’m doing will open the way for people to take a different path.”

With his neat coif, square jaw, and G-rated diction, Romney has always emanated a kind of old-fashioned civic starchiness. In the past, this quality has been the object of occasional ridicule. (During his 2012 presidential bid, reporters like me often snickered at his penchant for quoting lines from “America the Beautiful,” which he called his favorite of the “patriotic hymns.”) But in these decidedly more vulgar times, there is a certain appeal to the senator’s wholesomeness.

When I first caught up with Romney, in June, he was in a buoyant mood, preparing to deliver his “maiden speech” from the Senate floor later that day. I asked him how he was settling in. “This is great!” he replied. “I mean, everybody told me I was going to hate it here.”

I confessed that I was among those who thought he might not enjoy being the 97th most senior member of the Senate.

“I think people forget I worked for 10 years as a management consultant,” Romney said, referring to his time at Bain & Company. “Which meant I was able to make no decisions, I was able to get nothing done, and I had to try and convince people through a long process.” In retrospect, it seems, he was destined for the U.S. Congress.

Romney told me that he doesn’t think much anymore about his 2012 defeat to Barack Obama. “My life is not defined in my own mind by political wins and losses,” he said. “You know, I had my career in business, I’ve got my family, my faith—that’s kind of my life, and this is something I do to make a difference. So I don’t attach the kind of—I don’t know—psychic currency to it that people who made politics their entire life.”

Not everyone he’s met in the Senate shares this outlook, he said. “People are really friendly, they’re really nice—except Bernie,” he said, laughing. “He’s a curmudgeon. It’s not that he’s mean or whatever; he just kind of scowls, you know”—Romney hunched his back and summoned a Scrooge-like grunt. “For Bernie, it seems like this is kind of who he is. It’s defining. It’s his entire person. For me, it’s part of who I am, but it’s not the whole person.”

After he was elected in November, Romney began typing out a list on his iPad of all the things he wanted to accomplish in the Senate. It was 50 items long by the time he showed it to his staff, and though they laughed, he continued undeterred. By the time we spoke, it had grown to 60, with priorities ranging from complex systemic reforms—overhauling the immigration system, reducing the deficit, addressing climate change—to narrower issues such as compensating college athletes and regulating the vaping industry.

As he searched the Senate for legislative partners, Romney told me, he was warned that his efforts were likely doomed. Even in less polarized, less chaotic times, the kind of ambitious agenda he had in mind would be unrealistic. But Romney was steadfast in his optimism. “I’m not here to say it can’t happen,” he told me.

When I broached the subject of Trump that afternoon in June, Romney’s face didn’t register the familiar mix of panic and dread that most GOP lawmakers exhibit these days when faced with questions about the president. If anything, he seemed a little bored by the topic. I had heard repeatedly from people close to Romney that his decision to run for Senate was motivated in part by his alarm at Trump’s ascent. But he still seemed to believe that he could illuminate a path forward for his party without incessantly feuding with the president. “I’m not in the White House,” he told me. “I tried for that job; I didn’t get it. So all I can do from where I am is to say, ‘All right, how do we get things done from here?’”

Anyone familiar with the fraught history between Trump and Romney might have known that a detente was unsustainable. Trump has nursed a grudge since 2016, when Romney denounced him as a “phony” and a “fraud,” and warned of the “trickle-down racism” that would accompany his election. After he won, Trump briefly considered tapping Romney as his secretary of state, but the match was not to be. And in the years that have followed, the tension between the two men has only grown more exaggerated.

They manage that tension in different ways: While the president spent a too-online Saturday earlier this month unloading on Twitter—launching #IMPEACHMITTROMNEY into the canon of viral Trump taunts—Romney enjoyed a quiet afternoon picking apples with his grandkids in Utah and refusing to take the bait. When I met him in his office a couple of weeks later, I asked if the Twitter insults bothered him.

“That’s kind of what he does,” Romney said with a shrug, and then got up to retrieve an iPad from his desk. He explained that he uses a secret Twitter account—“What do they call me, a lurker?”—to keep tabs on the political conversation. “I won’t give you the name of it,” he said, but “I’m following 668 people.” Swiping at his tablet, he recited some of the accounts he follows, including journalists, late-night comedians (“What’s his name, the big redhead from Boston?”), and athletes. Trump was not among them. “He tweets so much,” Romney said, comparing the president to one of his nieces who overshares on Instagram. “I love her, but it’s like, Ah, it’s too much.” (After this story was published, Slate identified a Twitter account using the name Pierre Delecto that seemed to match the senator’s description of his lurker account. When I spoke to Romney on the phone Sunday night, his only response was, “C'est moi.”)

He understands, of course, that many of his Republican colleagues live in fear of being subjected to a presidential Twitter tirade. In fact, some believe that Trump’s targeting of Romney is intended as a warning to other GOP lawmakers lest they step out of line. That fear is one of the reasons his caucus has attempted such elaborate rhetorical contortions to defend Trump as the House impeachment inquiry turns up damning evidence. “I think it’s very natural for people to look at circumstances and see them in the light that’s most amenable to their maintaining power,” he told me in an interview last month at the Atlantic Festival.

Romney told me that he does not have an abstract definition of “high crimes and misdemeanors,” and that when it comes to identifying impeachable acts, he follows Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s famous standard for defining hard-core porn: “I’ll know it when I see it.” Asked if he’s seen it yet, Romney told me that he’ll make up his mind once he hears all the evidence at the trial: “At this stage, I am strenuously avoiding trying to make any judgment.”

In the meantime, Romney is leading the Republican revolt over the president’s recent decision to pull troops out of northern Syria, leaving America’s Kurdish allies behind. In a withering speech on the Senate floor last week, he condemned the administration’s betrayal of the Kurds, and called for hearings on the matter. He told me that he wants to see a transcript of the phone call between Trump and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan that preceded the troop withdrawal. “This is not just a disagreement on foreign policy,” he said. “This is a violation of fundamental American honor.”

Amid all the tumult, Romney has come to terms with the fact that there will be little progress on his legislative to-do list for the foreseeable future. (Between impeachment proceedings and next year’s elections, who has time to pass laws?) Nor is Romney especially well positioned to launch a bid for the Republican presidential nomination, despite endless fantasizing by pundits. (He has said he’s not planning to run again.) While his battles with the president have earned him plaudits from some in Utah—where support for Trump is uncommonly weak for a red state—he is widely viewed as a villain in MAGA world.

But Romney is looking beyond the next year, and beyond the president’s base, as he tries to lay the groundwork for a post-Trump Republican Party. While he acknowledges the failures of his own presidential campaign, he told me that he doubts Trump’s electoral coalition will be replicable in the long run. “We have to get young people and Hispanics and African Americans to vote Republican,” he said, adding that he hopes these voters will see his resistance to Trump as a sign that one day they could find a home in the GOP. If that seems naive, the senator is probably okay with it. In cynical times like these, someone has to serve as the guardian of lost causes.

After all, Romney said, “the president will not be the president forever.”