Column: Pelosi finds a way to save billions by cutting drug prices, but Big Pharma pushes back

A measure being pushed by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) is challenging the Washington assumption that bringing down drug prices is an impossible task — and its approach has been validated by nonpartisan legislative analysts.

The bill is H.R. 3, which was advanced Thursday by two House committees on party line votes. The bill would require Medicare authorities to negotiate lower drug prices directly with manufacturers, using a benchmark based on prices for the target drugs in six developed countries, which generally have lower prices than the United States.

Uniquely among drug price legislation coming out of Congress, the measure would put teeth into the negotiation process by penalizing drug companies that refuse to come to the table.

The lower prices under the bill would immediately lower current and expected future revenues for drug manufacturers, change manufacturers’ incentives, and have broad effects on the drug market.

— Congressional Budget Office

This approach was effectively endorsed by both the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office and the government’s own Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which found it would result in hundreds of billions of dollars in savings for Medicare enrollees, Medicaid, and American households generally.

The measure, which originally was labeled the Lower Drug Costs Now Act of 2019, is being renamed after Rep. Elijah Cummings, the Baltimore Democrat who was a long-term voice in favor of lowering drug prices and who died on Thursday.

The CBO analysis projects savings of $345 billion for Medicare over seven years and says the changes forced upon the drug market would also result in lower premiums for commercial health insurance.

“The lower prices under the bill,” CBO wrote Oct. 11, “would immediately lower current and expected future revenues for drug manufacturers, change manufacturers’ incentives, and have broad effects on the drug market.”

It’s hard to believe that anyone was taken in this summer when a handful of drug companies announced rollbacks of price increases or price freezes on some of their drugs, ostensibly in response to jawboning by President Trump.

The CMS estimates the reduction in U.S. healthcare spending at $481 billion over 10 years, including $158 billion in household savings through lower insurance premiums and prescription co-pays, and $219 billion in savings on Medicare Part D prescription plans, Medicaid, and other federal programs. CMS figures that the bill could produce discounts as high as 72% from existing prices for some drugs in the first year.

The drug industry doesn’t care for this at all. “This type of policy would have a devastating effect on the industry and the patients that we serve,” Stephen J. Ubl, chief executive of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, declared earlier this month. Among its impacts, he said, would be a reduction in research and development for new drugs. We’ll get to that argument in a moment.

Big Pharma has an ally in the Republican majority in the Senate, where Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has declared the bill dead on arrival. “Socialist price controls will do a lot of left-wing damage to the healthcare system,” he said last month after Pelosi rolled the bill out. He pledged not to allow it to come to the Senate floor.

The industry also has an ally in the Trump administration. As recently as Thursday, CMS Administrator Seema Verma told an audience at a Time magazine event in New York that “turning over negotiations to the government doesn’t work well.” (She must not have read her own agency’s analysis, which was issued Oct. 11 and concluded that it would work quite well, thank you.)

But McConnell and Verma may be trying to hold back the tide. The public is strongly in favor of capping prescription prices, and the Pelosi bill’s method is a sound one.

Let’s examine how it would work.

Nothing brings an industry’s dirty little secrets to light as effectively as litigation, especially when the industry gives up those secrets voluntarily, in the service of making more profit than it could obtain by remaining silent.

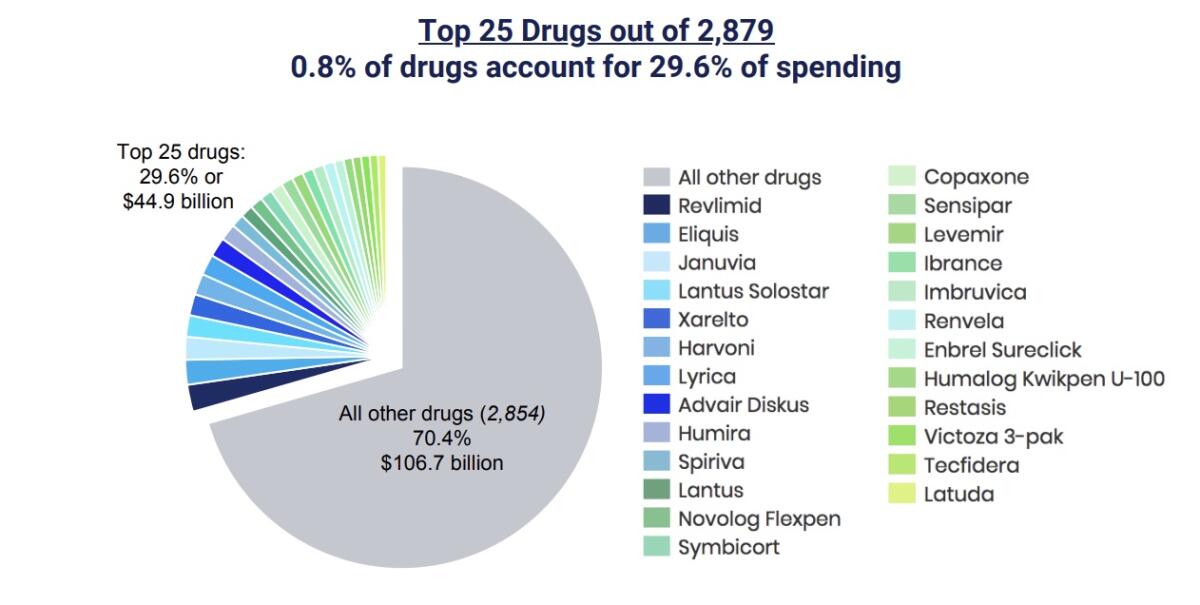

The measure would require the Secretary of Health and Human Services to negotiate prices for at least 25 drugs every year, starting in 2021, for Part D, the Medicare prescription program. The target drugs would be drawn from the list of 125 drugs with the highest spending in Part D and the commercial market. (Those top 125 drugs account for nearly two thirds of all Part D spending, according to Patients for Affordable Drugs.)

In the first year, negotiations would also have to be conducted for insulin, the diabetes drug that has been a particular focus of industry profiteering in recent years.

The negotiated price can’t be higher than 120% of the average cost for the given drug in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom. For drugs not sold in those countries, there’s an alternative formula based on their average wholesale prices in the U.S.

The problem with drug price negotiations always has been how to get the drug makers to participate. The Dept. of Veterans Affairs, which has had the most success in squeezing companies for discounts, does it by maintaining a tight list of accepted drugs known as a formulary, and threatening to toss drugs off the list if their manufacturers don’t play ball.

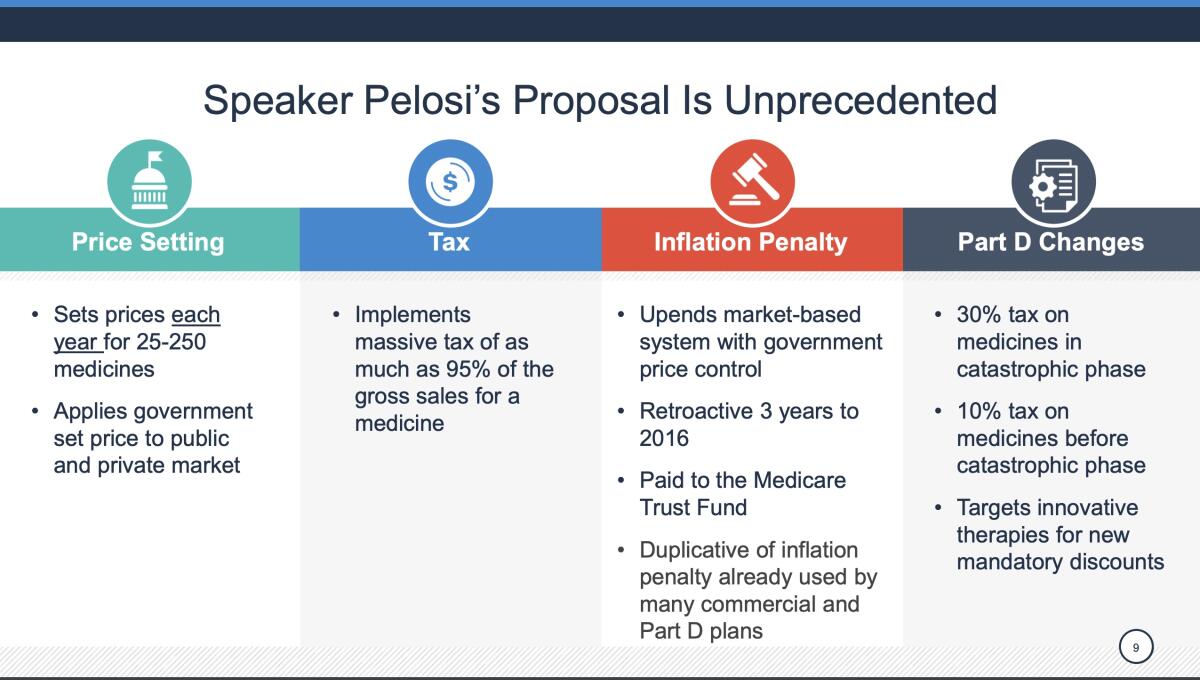

That won’t work for Medicare or the commercial market, where customers want and need access to a broader formulary. The approach of H.R. 3 is to impose a stiff excise tax of as much as 95% on companies that refuse to negotiate. The tax isn’t deductible from income tax. As a result, the CBO says, “the combination of income taxes and excise taxes on the sales could cause the drug manufacturer to lose money if the drug was sold in the United States.”

The CBO and CMS both acknowledge that there are a few ways drug companies could try to game this process. For example, they could raise the price of drugs in the six benchmark foreign markets, giving them more headroom under the 120% cap. They could mask real prices in those markets through rebates or other complexities.

President Trump’s meeting Tuesday with pharmaceutical executives was a theatrical display of chumminess in which all the parties seemed to share deep regret over high and soaring drug prices.

But that might not be as easy as it sounds. Those foreign countries have their own rules about drug pricing, and if H.R. 3 were to pass, one would expect them to keep a gimlet eye out for price manipulation by American firms. The bill also requires the companies to disclose to the government its foreign prices and sales, which might limit their ability to engage in international price-fixing.

The main downside to the bill identified by the legislative analysts and bruited about by the drug industry is that lower profits would lead to a reduction in R&D spending. Phrma talks about a “hit” of more than $1 trillion over 10 years on “biopharmaceutical innovators” and a “loss of hope for millions of patients” awaiting R&D breakthroughs for their conditions.

Is this a plausible fear? Only on the surface. The drug industry has consistently inflated the cost of bringing new drugs to market, with the assistance of a research group at Tufts University heavily funded by the industry itself. The latest estimate published in 2014 was $2.6 billion, but it’s been widely questioned, in part because the data Tufts used to concoct it are confidential. That didn’t keep it from being cited by a gullible President Trump. As we’ve reported, more objective estimates place the cost per drug at less than $100 million.

Profiteering in the drug business has been generating outrage for months now.

Nevertheless, the industry has long claimed that it needs huge profits to fund R&D to get what it wants out of Congress — tax breaks for drugs for rare diseases, faster drug approvals by federal regulators and stronger protection against competition from generics.

The claim was debunked in 2017 by a team from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, which concluded that the “excess revenues” earned by 15 leading companies by charging premiums in the United States over foreign prices averaged 163% of what it spent on R&D.

We can see this effect by examining drug company financial disclosures. To choose a couple at random, Pfizer earned $11 billion in profit on $53.6 billion in revenue in 2018 but spent $8 billion on research and development. Johnson & Johnson earned $15.3 billion in profit last year on $81.6 billion in revenue but spent $1`0.7 billion on R&D.

As the Sloan Kettering researchers asserted, “lowering the magnitude of the US premium to a level where it matches global R&D expenditures across the 15 companies we assessed would have saved US patients, businesses, and taxpayers approximately $40 billion in 2015.” That would amount to more than 12% of total U.S. drug spending that year.

The procedure embodied in H.R. 3 would go far to put a leash on rising drug prices in the U.S. and ending our status as the most easily exploited drug market on the face of the Earth. The arguments you’ll hear against it may be mouthed by Republicans in Congress, but they’re merely reading from the book of Big Pharma talking points.