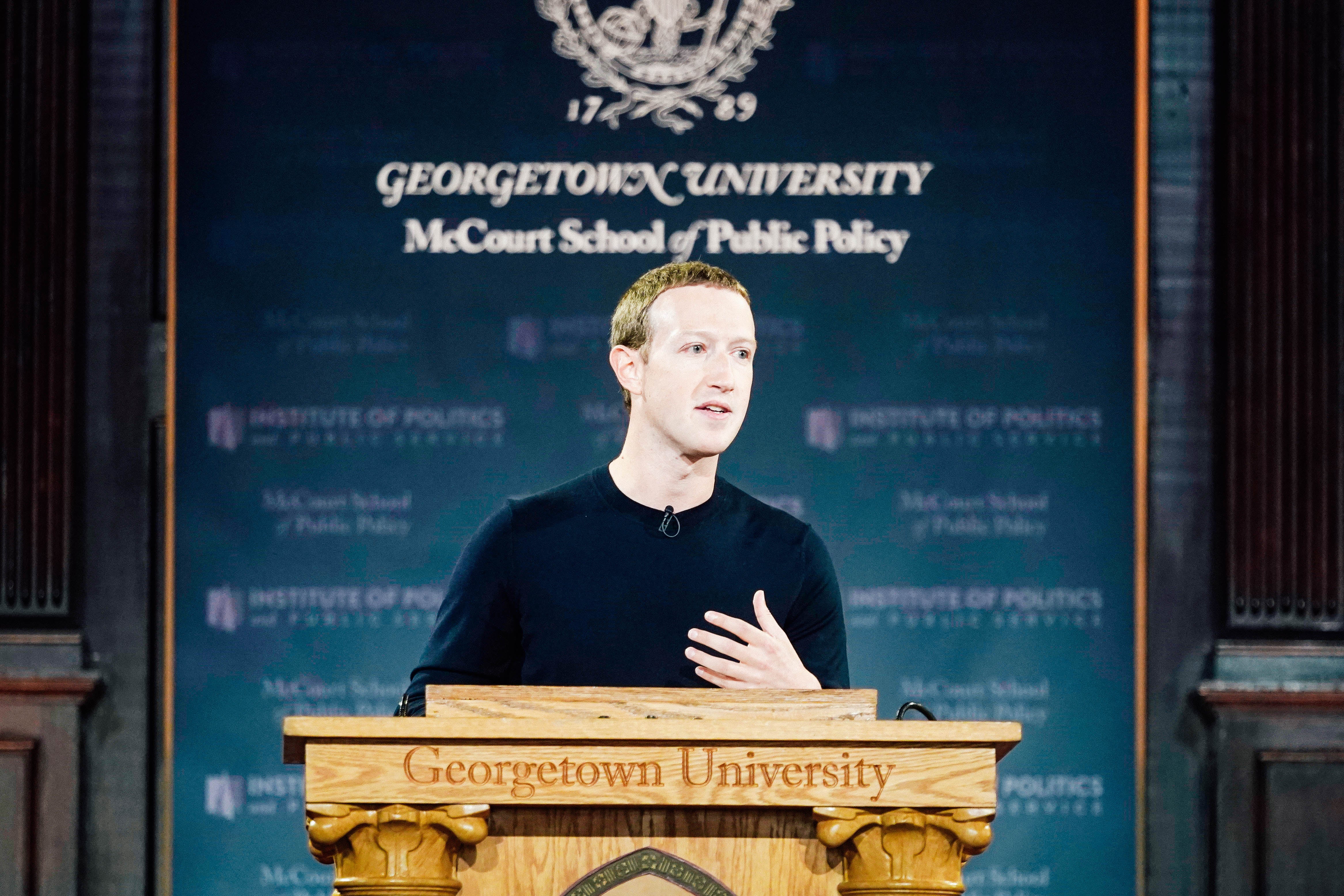

Mark Zuckerberg visited Georgetown University on Thursday to deliver the “most comprehensive take” he’s ever shared on his views on free speech. No wonder that Zuckerberg began his appearance by revising his company’s well-known origin story, explaining that as a college student he believed giving voice to more perspectives might have prevented the Iraq war, and that this inspired him when he was developing Facebook. (Odd, considering Facebook famously grew out of FaceMash, a hot-or-not website featuring pictures of Harvard students.)

The speech situated the company as a torchbearer of the fundamental American tradition of free speech, which Zuckerberg stressed is no easy task, especially when the company is under the immense pressure it has faced in recent years: “Some people believe giving more people a voice is driving division rather than bringing us together,” Zuckerberg said. “More people across the spectrum believe that achieving the political outcomes they think matter is more important than every person having a voice.”

These people have a “dangerous” opinion, Zuckerberg said, but he never specified who those people are. I’ve been covering the debate over Facebook’s content moderation and speech policies for the past two years, following its critics and defenders as the company has dealt with harms resulting from its social network in the United States and abroad. As far as I can tell, none of the critics who are calling for Facebook to act faster, more consistently, and more transparently when it comes to removing harmful content—that is, some speech—are asking for Facebook to help them achieve political outcomes by silencing others.

Many of the company’s critics—academics, human rights advocates, opinion journalists—are asking Facebook to protect the people who have come to depend on it and who wish to speak freely and engage in political and social life from being harmed by content that is dangerous for democratic participation, has stoked discrimination of minority groups, or has the intention of promoting real-world violence. This isn’t about any particular political agenda. It’s about protecting and creating spaces that make politics possible.

Zuckerberg did say he agrees with these areas of protecting users. When it comes to hate speech, for example, he explained that Facebook uses dehumanization as a yardstick for what should and should not be allowed, since, as Zuckerberg put it, when someone says “all Muslims are terrorists—that makes others feel they can escalate and attack that group without consequences.” He also noted that the company takes misinformation around health advice seriously, and that it is focused on removing “inauthentic” accounts that are not run by the people they purport to be. In his speech, Zuckerberg identified a number of challenging areas where users can be harmed, explained what his company is doing about them and what it can’t, and quickly returned to his central question: As he put it at one point, “Will we continue fighting to give more people a voice to be heard, or will we pull back from free expression?”

Over the last few years, Facebook has hired thousands of workers and rolled out numerous policies with an emphasis on when it will intervene with content. But if the company is centering “free speech” as its central value, and explicitly defining areas in which it will allow some powerful users to lie, as Zuckerberg did, it’s worth reviewing how Facebook’s version of it has been going up to this point:

• There was the United Nations report that detailed how hate-filled Facebook posts have worked to amplify deadly ethnic tensions in Myanmar, where hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims have fled from what the U.N. suspects may be genocide.

• There were the thousands of accounts puppeted by Russian operatives that took a starring role in the well-documented Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, stoking racial divides and actively attempting to dissuade people from voting in an effort to sway the election for Donald Trump. Plus the more than 100 Russian troll accounts that were found muddying the waters of the 2018 midterms, too.

• It was only in 2017 that it was found that Facebook allowed advertisers to reach people based on their interest in being a “Jew hater,” a practice Facebook stopped—but only after journalists reported on it, leading to public condemnation.

• There was that video broadcast live on Facebook earlier this year by the terrorist who murdered 50 people at two separate mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, that the company was unable to detect and take down before it was copied and reposted 1.5 million times on Facebook in a 24-hour period.

These are only a fraction of the harms Facebook critics have pleaded with the company to deal with—and which the company does deal with, albeit usually only after public outcry begging it to do better. Again, this doesn’t include the overwhelming majority of types of content people might put on Facebook, which no one is asking Facebook to curb, although Zuckerberg’s speech seemed to suggest otherwise. It’s the extreme yet consequential cases that illustrate the limits of the CEO’s framing of social media as a neutral forum where all voices have equal weight. That isn’t how Facebook works since its news feed algorithm can amplify emotional and hateful content. And it isn’t how speech often intersects with power.

Free speech isn’t “protected” when hate that can inspire violence is allowed to flourish. When hate and disinformation have a platform, some users can’t safely speak there and often flee, even if they’re technically allowed to speak, too. On Facebook, the answer to harmful speech shouldn’t be more speech, as Zuckerberg’s formulation suggests; it should be to unplug the microphone and stop broadcasting it. Of course, making the decision to pull the plug on someone isn’t always easy, which Zuckerberg admits, and it’s why Facebook recently established an “independent oversight board“ and appeals process for when this does happen. But as a value, he seems to have given user safety a supporting role.

All of this may feel like an abstract tension, but there is an important area where user safety and “free speech” have come into conflict, and Zuckerberg addressed it directly. “We don’t fact-check political ads,” he said, explaining a new policy that was criticized after Facebook allowed a Facebook ad from Trump that contained unevidenced and untrue claims about Joe Biden’s son Hunter to remain on the site. (CNN refused to air the same ad because of these inaccuracies.) Facebook’s critics argue that the company is causing harm by allowing politicians to lie, since that could lead people to make voting decisions based on information that isn’t true.

The company says it’s not fact-checking political ads so people can see what politicians are saying—a strange argument, considering politicians are free to write whatever they want on their own websites but aren’t owed free rein on Facebook unless Facebook decides they can have it. Here, the value of free speech has aligned precisely with a choice that makes the company money and insulates Facebook from criticism from the right.

Zuckerberg found a loftier justification. From the stage, he invoked numerous figures who fought against the American institutions of slavery and segregation. He claimed these people were only able to do so because their right to free speech was a lifeline. But many of these figures were also victims of disinformation campaigns that stoked hate and violence against them. “I’d like to help Facebook better understand the challenges #MLK faced from disinformation campaigns launched by politicians,” Bernice King, the daughter of Martin Luther King Jr., wrote on Twitter. “These campaigns created an atmosphere for his assassination.”

Disinformation makes struggles for justice—and a voice—harder, and it often strands leaders of marginalized groups in the trap of constantly having to correct the record about details that have little to do with the issues they actually are trying to address. Russian trolls may not be officially welcome to peddle disinformation on Facebook anymore, but politicians are.

It was helpful to hear Zuckerberg’s comprehensive take on all of this—where he sees the complexity of the speech issues Facebook is confronting, what he thinks of his critics, and why he thinks the free speech rights of users who pay to lie, and who carry the threat of potentially regulating his company, are important. What he hasn’t noticed is clarifying, too. By elevating some voices, and allowing them access to Facebook’s powerful amplifier, others could lose their ability to speak.